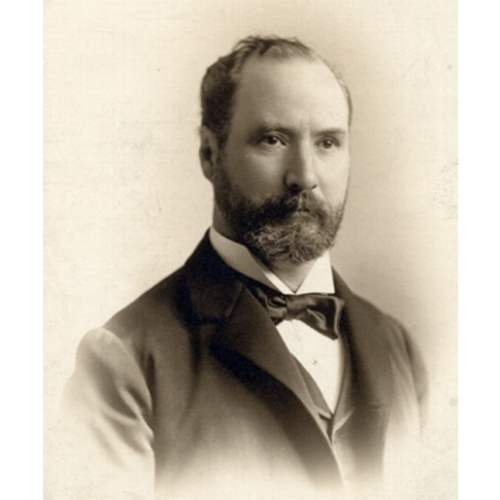

BICKERDIKE, ROBERT, businessman, politician, and social reformer; b. 17 Aug. 1843 in Kingston, Upper Canada, son of Thomas Bickerdike, a farmer, and Agnes Forster Cowan; m. 4 Dec. 1866 Helen Thomson Reid (d. 1907) in Montreal, and they had at least three sons and six daughters; d. 28 Dec. 1928 in Lachine, Que.

Robert Bickerdike’s ancestors, of Norman descent, hailed from one of the oldest families in England, the de Bickers, who had settled in Yorkshire late in the 11th century. In memory of Robert Bickerdike, who was executed for his Roman Catholic faith in 1585, the eldest son of every branch of the Bickerdike family was named Robert.

Born in Berkshire, Thomas Bickerdike, the youngest son of a Protestant branch of the family, had arrived in the Canadas by 1820. He left Upper Canada in the late 1840s and moved to Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague, in Beauharnois county, Lower Canada, where he purchased a small farm. His son Robert was educated in the village of Beauharnois and probably became fluent in French at that time. He worked on the family farm until age 17 and then moved to Montreal, where he became a butcher. Sometime in the mid 1860s he started a pork-packing business. In June 1875 he formed a partnership with Duncan McCormick as the Robert Bickerdike Company, pork butchers and packers in Saint-Henri (Montreal) and shortly afterwards he moved to that town. The following year he entered the livestock export trade, which was just getting under way; he would eventually become one of the most successful cattle exporters in Canada.

In 1881 Bickerdike organized the Dominion Abattoir and Stock Yards Company Limited in Saint-Henri with butchers Edward Charters, William Morgan, and Robert Nicholson, leather manufacturer Pierre Claude, soap and oil maker William Strachan, and cattle dealer Robert J. Hopper. The firm had an authorized capital of $200,000. Bickerdike was its managing director. To protect his growing investments, he branched out into insurance, founding the Live Stock Insurance Company in 1884; he would act as its president in 1898. By the mid 1880s, in addition to running his abattoir and cattle export business, he was acting as an insurance and shipping agent. During this decade he also served as a cattle inspector for various insurance companies. In 1887 he was secretary of the Dominion Livestock Association.

In 1892 the cattle export trade was severely disrupted by a British embargo on Canadian livestock which originated with the discovery of diseased cattle. Bickerdike vigorously objected to the embargo and on several occasions asked the British Board of Agriculture to lift it. He insisted that the Canadian cattle were not diseased and that the British were using the embargo as a pretext to protect their domestic trade from competition. Concerned that the dispute would threaten the broader trade relationship between Canada and Great Britain, he cautioned the British against looking to France and the United States as alternative trading partners. The embargo would still be in effect in 1912.

In 1893 Dominion Abattoir was reorganized. With the exception of Bickerdike, the original partners left and were replaced by cattle exporter Louis Delorme and accountant Wellington E. Bell. The firm’s capital, now $250,000, could be expanded to $1,000,000 and the company obtained the right to issue bonds, acquire other firms, and construct waterworks. Seven years later it was renamed Robert Bickerdike and Company Limited. Meanwhile, Bickerdike’s involvement in insurance became an increasingly important part of his business activities. He was appointed branch manager of the Western Assurance Company, a general insurance company, in 1900 and he would continue with this firm until 1924. In addition he acted as branch manager for the Quebec Fire Assurance Company in 1900 and 1901, and would serve in the same capacity for the Union Marine Insurance Company of Halifax, Nova Scotia from 1901 to 1912. In 1910 he began to appear on the boards of various insurance companies; he served as a director of several well-known firms, including the Canada Life Assurance Company from at least 1912 to 1917.

Bickerdike had left the cattle export trade in 1911. He would continue alone in Robert Bickerdike and Company in insurance and finance until 1919. His knowledge of finance had led him to serve from 1891 to 1911 as vice-president of the Banque d’Hochelaga. In 1911, with Conservative mp Rodolphe Forget*, he founded the Banque Internationale du Canada, an institution which focused on attracting investment from France. Over a year later tension between French and Canadian investors brought the institution to bankruptcy.

Active in a wide range of businesses, Bickerdike had been a founder in 1892 of the St Henri Light and Power Company (renamed the Standard Light and Power Company the following year) and he served as its president from at least 1898 to 1905. He presided over the Montreal and Great Lakes Steamship Company from about 1909 to 1912 and the Canada Securities Corporation from 1910 to 1914. He was a director of numerous firms, including the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of Canada Limited from about 1909 to 1917.

An important contributor to Montreal’s rise as the dominant Canadian urban centre in the early 20th century, Bickerdike had been president of the Montreal Board of Trade in 1896. A member of the Montreal Harbour Commission from 1896 to 1906, he served for a time as acting chairman. He invested much time and energy in building up the harbour and as an mp he defended its interests in the House of Commons. Bickerdike pier remains a lasting monument to his important contributions.

While a resident of Saint-Henri, Bickerdike had sat for a few months in 1875 on its town council. His principal foray into municipal politics, as pro-mayor of Summerlea (Lachine), took place in 1895-96, soon after he moved there. He departed from his family’s long-standing affiliation with the Conservatives and entered provincial politics in 1897 as a Liberal, winning in Montreal, Division No.5. In 1900 he began a 17-year stint in federal politics. He was easily elected under the Liberal banner for St Lawrence, a Montreal riding with a large French Roman Catholic population and a smaller Jewish one. As a politician, he was best known for his stand on important social issues, but his parliamentary record also includes several short speeches aimed at furthering economic interests closely related to his business endeavours, including the cattle export trade. A man the Ottawa Citizen once described as a “pillar” of the Liberal party, he sat in the house through much of Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s tenure as prime minister. Although he was a lifelong friend of Laurier, he broke with his leader during World War I over Laurier’s position against conscription. His letter of resignation in 1917 mentioned the military service of his sons and grandsons.

Most noteworthy were the positions Bickerdike took as a politician on some of the dominant social and cultural issues of the early 20th century. A champion of the linguistic and confessional rights of minorities, he once referred to Quebec as a model with regard to its treatment of the English Protestant minority. A member of the Protestant committee of the Council of Public Instruction from 1911 to 1923, he felt that Quebec’s record vis-à-vis its minorities was particularly strong with regard to schooling. In 1905, on the controversial question of linguistic and confessional school rights for the French Catholic communities in the newly created provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan [see Laurier], he had pleaded in favour of the minorities. He warned against those who sought to promote conflict in order to gain political advantage.

A Presbyterian of unquestionable faith, Bickerdike represented a federal riding with an important Jewish electorate and he enjoyed referring to himself as the Jewish representative in the house. In 1906 he challenged the prevalent thought that only Sunday, the Christian day of rest, should be respected. While other mps contended that Jews were merely guests in a Christian society and therefore subordinate to the religion of the majority, Bickerdike defended their liberty to observe a different sabbath. Jews, he told his peers, deserved equal respect in practising their religion and should therefore be allowed to close their businesses on Saturday and open them on Sunday.

Throughout his political career Bickerdike demanded equal rights for all citizens regardless of denomination. In 1910 he moved that the protection provided to young Protestants and Catholics under the Juvenile Delinquents Act of 1908 be extended to include all others, especially Jews. On another occasion, he expressed concern that denominational quotas might be used in educational institutions in Canada. In 1912 he proposed to have removed from Queen’s University’s charter the reference to its “distinctively Christian” character and the requirement of “the profession of Christianity” for hiring purposes. In 1917 he urged that the vote be extended to “the loyal women of Canada” and that they receive the same political rights and privileges enjoyed by men. Over the course of his political career, Bickerdike was an outspoken supporter of the poor and the disenfranchised and a standard-bearer for liberal ideals. Many of his spirited speeches evinced righteous indignation at the prevailing attitudes and laws of the day. Whether pushing for prison reform, lobbying on behalf of religious minorities, or advocating the prohibition of cigarette sales to minors, he worked tirelessly.

For Bickerdike, the abolition of capital punishment was an imperative and to some extent his life’s mission. Few spoke as loudly or as eloquently as he did for this reform. In 1914 and again in 1916 he introduced a bill to replace the death penalty with a life sentence. He opposed capital punishment on many grounds, considering it an insult to Christianity and religion in general and a blot on any civilized nation. “There is nothing,” he stated in the house, “more degrading to society at large . . . than the death penalty.” He also spoke of class disparities, pointing out that the punishment was administered to the poor far more often than to the wealthy. He refuted the notion that state-sponsored killing acted as a deterrent to murder and cautioned against the possibility of mistake. Though he never stopped fighting for this cause, he did not live to see it realized; capital punishment would not be abolished in Canada until 1976.

In private life Bickerdike was a founder and president of the National Prison Reform Association, established in 1916. Three years later it merged with the Honour League of Canada to become the Canadian Prisoners’ Welfare Association. This body lobbied against capital punishment, helped care for prisoners’ families, and sought employment for offenders following their release. Bickerdike would serve as honorary president until his death. In the commons he called attention to the awful conditions in Canadian penitentiaries. His strong Christian faith underpinned his demands for prison reform. In 1917, in the midst of World War I, he moved a resolution in the house to grant all prisoners the opportunity to enlist for active service, and thereby give them the opportunity to redeem themselves while aiding the cause of their country.

Bickerdike was a leader in community works. His contributions to hospital activities included service as governor of the Royal Victoria Hospital starting in 1896, as life governor of the Montreal General Hospital from 1898, and as both governor and president for a time of the Western Hospital of Montreal. He was president of the St George’s Society in 1912. His interest in recording Canada’s heritage led to his involvement in the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Montreal. Known for his personal generosity, he had established, according to an obituary, an “understanding with the minister of his church [in Lachine] that no one was to go hungry.”

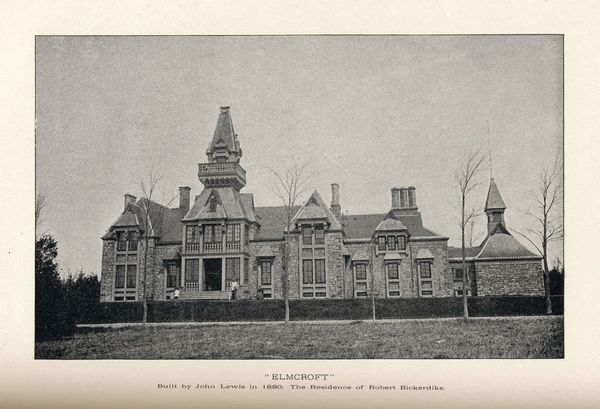

An invalid for the last three years of his life, Robert Bickerdike died on 28 Dec. 1928 at his home, Elmcroft, in Lachine. Although he never sought recognition, he was offered a knighthood for his support of the war effort. Before the honours list could appear, however, the House of Commons adopted a resolution in 1919 which temporarily ended the granting of titles to Canadians. He was remembered as someone with a great appetite for life and was universally admired for his unyielding integrity, generosity, and charity.

ANQ-M, CE601-S120, 4 déc. 1866; TP11, S2, SS20, SSS48, vol.6-o, 31 juill. 1875, no.450; vol.11-o, 15 juill. 1911, no.64; vol.17-o, 6 janv. 1919, no.1265; vol.21-o, 14 mai 1900, no.1087. LAC, MG 26, G. Gazette (Montreal), 29 Dec. 1928. R. C. Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896-1921: a nation transformed (Toronto, 1974). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1900-17; Parl., Sessional papers, 1891, no.7b. Canada Gazette, 26 Feb. 1881. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). CPG, 1897-1917. Directory, Montreal, 1875-1917. DPQ. H. B. Neatby, Laurier and a Liberal Quebec; a study in political management, ed. R. T. Clippingdale (Toronto, 1973). Que., Statutes, 1893, c.79; 1900, c.80. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec. The storied province of Quebec; past and present, ed. W. [C. H.] Wood et al. (5v., Toronto, 1931-32).

Cite This Article

Jack Jedwab, “BICKERDIKE, ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bickerdike_robert_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bickerdike_robert_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jack Jedwab |

| Title of Article: | BICKERDIKE, ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 24, 2025 |