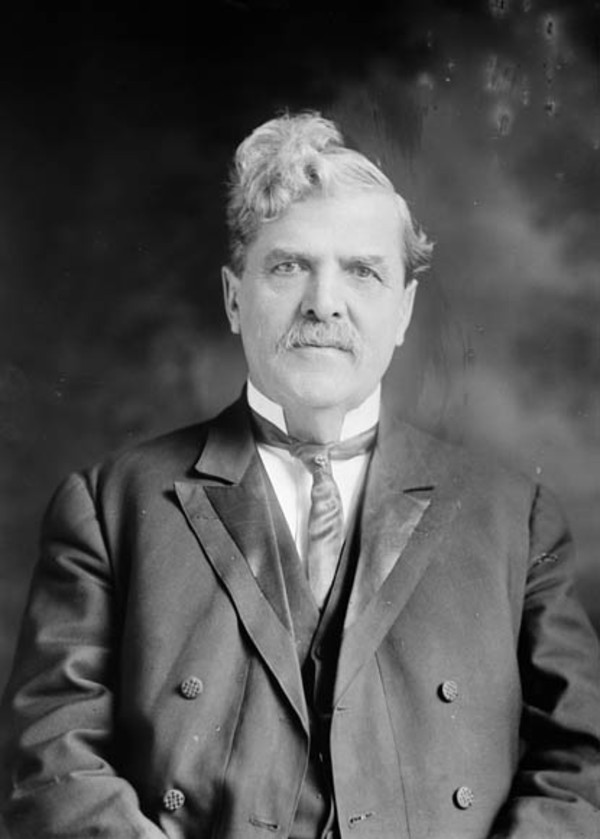

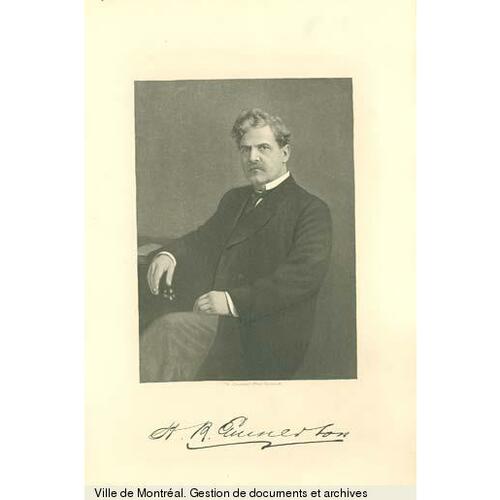

EMMERSON, HENRY ROBERT, lawyer and politician; b. 25 Sept. 1853 in Maugerville, N.B., son of Robert Henry Emmerson, a Baptist clergyman, and Augusta A. Read; m. 12 June 1878, in Moncton, N.B., Emily Charlotte Record (d. 1901), daughter of Charles B. Record*, and they had one son and four daughters who survived him; d. 9 July 1914 in Dorchester, N.B.

Of English and loyalist descent, Henry R. Emmeron acquired his education at numerous institutions in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and New England. In 1871, after two years at Acadia College in Wolfville, N.S., he attended a Boston commercial college and was given a position in Joseph Read and Company, his grandfather’s firm of quarrymen and stonecutters. Three years later he went to Dorchester, where he read law with Albert James Smith* and then with Albert J. Hickman. He left in 1876 to attend Boston University law school and graduated the following year, winning the prize-essay contest for a paper on “The legal condition of married women.” In November 1877 he entered a partnership with Hickman and in 1878 he was called to the bar. The firm was subsequently restructured as Emmerson and Read, then Emmerson, Chandler, and Chapman, and finally Emmerson and Chandler.

Emmerson quickly built up a lucrative law practice and extensive business interests. He acted as executor under the will of Smith, among others, became involved in woollen manufacturing, served as a director of the Maritime Baptist Publishing Company Limited, and until its purchase by John Thomas Hawke in 1887 had a financial interest in the Moncton Transcript, a partisan Liberal newspaper. During the course of his career he was president of the New Brunswick Petroleum Company Limited, the Acadia Coal and Coke Company, and the Sterling Coal Company, as well as a director of the Record Foundry and Machine Company.

Entering federal politics in February 1887, Emmerson contested Westmorland for the Liberals against Josiah Wood* of Sackville. When he lost, he petitioned the election court, alleging more than 500 acts of bribery and corruption on the part of his opponent. This action set in motion a series of events that led to the jailing of John T. Hawke, who had made the charges a cause célèbre [see John James Fraser*] and had thereby attracted for Emmerson attention that was to boost his political career. On 28 Sept. 1888 Emmerson won a provincial by-election in Albert. He had the tables turned on him when the unsuccessful candidate protested the results, and a new election was ordered for 23 Feb. 1889, which Emmerson won. He was defeated in the general election the next year, but his political reputation had been enhanced. Meanwhile, he had distinguished himself in the House of Assembly as an advocate of women’s suffrage. In a debate in April 1889 on whether widows and single women of property or sufficient income should have the vote, he was one of seven members who supported this extension of the franchise. Indeed, he favoured residential suffrage for both men and women, arguing that denying women the right to vote was “a relic of barbaric prejudice.”

Emmerson still had his sights on a federal seat and on 5 March 1891 he unsuccessfully contested Albert for the Liberals, losing to Richard Chapman Weldon*. Six days later Premier Andrew George Blair*, who had put together a coalition that was emerging as the provincial Liberal party, appointed him to the Legislative Council of New Brunswick. The arrangement included agreement on his part, as on the part of the other new appointees, that he would approve legislation to abolish the upper chamber. Having become government leader in the Legislative Council, in March 1892 he was made president of the Executive Council. On 10 October he took office as chief commissioner of public works, and some days later he successfully contested Albert in the provincial election.

As chief commissioner, Emmerson was responsible for provincial highways and bridges. Against the previous practice of building most bridges of wood, he vigorously supported the construction of more permanent bridges, a policy that was controversial both for increasing the public debt and for the supposed manner in which contracts were awarded. Political activity in the 1890s was marked by continued efforts to promote women’s suffrage, all of which Emmerson supported. Another feature was the repeated attempts of Herman Henry Pitts to re-ignite a controversy over public schools [see J. J. Fraser]. Emmerson, who had strong Protestant connections, was able to use them effectively in 1893 when Pitts accused the government of “bowing to Rome” in education: as an Orangeman and the representative of “an extreme Protestant constituency,” he argued, he “would not remain in the government an hour” if that were the case. He later labelled Pitts “a reckless fanatic . . . a political hypocrite who wished to array class against class and creed against creed.”

The political climate changed in 1896 when Premier Blair moved to the federal government. He was replaced by James Mitchell*, who was obliged to resign in 1897. The two contenders for the premiership then were Emmerson and Lemuel John Tweedie. On 29 October Emmerson succeeded to the office, retaining his portfolio as chief commissioner of public works.

Emmerson’s administration was concerned in particular with economic development. In addition to continuing support for dairy farming, in 1898 it brought in a bill to promote the growing of wheat, a policy which had limited success. That year steps were taken to encourage visits of tourists and sportsmen to the province, and in 1898 and again in 1900 efforts were made to advance the settlement of vacant crown lands. Meanwhile the government initiated legislation to promote the development of natural gas and petroleum, and following upon the opinion rendered by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the matter of federal-provincial responsibility for the fisheries, it moved to regulate those fisheries that clearly fell within provincial jurisdiction. Emmerson did not, however, have the political support necessary to achieve universal suffrage. When on 13 April 1899 he moved a motion to grant women the full franchise, he would again be one of only seven supporters.

By late 1898 Emmerson was seeking to renew his government’s mandate. An election issue had been provided in July when the convention of the provincial Conservatives decided that in the next election candidates should be supported who were in sympathy with federal Liberal-Conservative principles. Emmerson dissolved the legislature in January 1899 and campaigned on the issue of “neutrality in Dominion federal politics with provincial interests paramount.” His supporters won an overwhelming victory. In the words of the Saint John Globe, local politics was not much affected by the “principles and ideas” of the two national parties but was rather determined by “other motives, such as that of control, that of the disposal of offices, and that of the bestowal of patronage.”

One of the successful Conservative candidates in this election was John Douglas Hazen*, a dynamic Saint John lawyer who had campaigned in part on Emmerson’s handling of contracts as chief commissioner of public works and who now succeeded the defeated leader of the opposition, Alfred Augustus Stockton*. In the legislature Hazen repeated his attacks but overplayed his hand when he suggested – unintentionally, he claimed – personal dishonesty on the part of the premier. The government appointed a committee of inquiry, and in 1900 it released a report in which Hazen’s charges were found to be unsubstantiated.

By this time Emmerson had had enough of provincial politics. Seeking new avenues, he solicited an appointment to the Supreme Court of New Brunswick. When it was not forthcoming, he decided to try again for a seat in the House of Commons, at Blair’s urging and on his promise, Emmerson recalled, that “he would leave very much ICR [Intercolonial Railway] patronage in my hands.” Emmerson resigned as premier on 31 Aug. 1900 and successfully contested Westmorland in the federal election in November. It soon became clear that Blair, then minister of railways and canals, had no intention of abandoning his control of patronage in Westmorland – the ICR shops were in Moncton, where the railway was the largest employer – and a bitter relationship developed between the two, with an at times exasperated Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier trying to keep an uneasy peace.

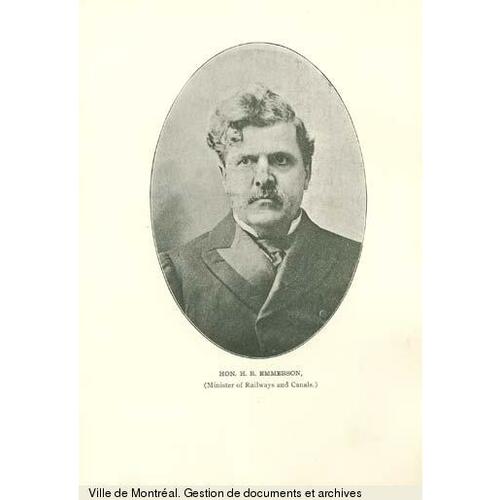

When Blair resigned in 1903, pressure mounted on Laurier to make Emmerson minister of railways and canals, the portfolio most wanted by Maritime politicians. Laurier clearly had doubts and delayed his decision for several months. Finally, on 4 Jan. 1904, he informed Emmerson that the ministry was his, but he cautioned that “should I deem it advisable . . . at any time in the public interest . . . to make any changes in the cabinet or to ask for your portfolio, your resignation would be at my disposal.” The reservations were based on Emmerson’s well-known drinking problem.

Shortly after taking office on 15 Jan. 1904, Emmerson was asked in the commons if he approved of patronage in ICR dealings. Refusing to be hypocritical, he responded, “As long as we have control of the government of Canada and as long as we have a government operated road, the government . . . will ask for recommendations from its friends and not [from] those who are opposed to it.” The ICR was, in fact, one of the government’s problems, beset by substantial operating deficits, largely because of its low freight rates. Emmerson in 1904 rejected increasing rates because he saw the railway as fulfilling an agreement made with the Maritime provinces at the time of confederation. In 1905–6, however, after he had undertaken a thorough inspection of the line and consulted widely with its staff, some rates were increased. Many organizational changes also took place, a more efficient accounting system was introduced, and the earlier policy of easy issue of passes was restricted. Emmerson had hoped to extend the ICR westward to tap the grain fields of the prairies, but he did not oppose the building of the National Transcontinental, though he had a concern that it might adversely affect the ICR. From his own political perspective, his constituents would welcome another national railway connecting with Moncton.

Elsewhere, Emmerson was able in 1906 to bring together all the groups involved in the construction of new docks and railway terminals at Quebec, and work was continued energetically on the Trent Canal in Ontario. In 1906 as well he succeeded in having private telephone companies placed under the control of the Board of Railway Commissioners, which was given the power to compel long-distance services to provide exchanges to local telephone companies [see Charles Fleetford Sise]. Emmerson’s personal interests, however, were concentrated on the Maritimes, and he promoted the amalgamation with the ICR of many unprofitable branch lines in the region. Much concerned with the welfare of railway employees, he improved their working conditions and in 1907 sponsored legislation to establish the Intercolonial and Prince Edward Island Railways Employees’ Provident Fund. It provided pensions for employees who retired or who from illness or other causes were prevented from performing their duties. Emmerson’s greatest political triumph had occurred after the ICR railway shops in Moncton were destroyed by fire on 24 Feb. 1906. Fearing a move by Halifax or Rivière-du-Loup, Que., to obtain the new headquarters, within hours Emmerson had met with Laurier who agreed to the rebuilding and expansion of the shops in Moncton. Emmerson’s status in his constituency was from then on unshakeable.

In addition to his difficulties with alcohol, Emmerson acquired the reputation of a womanizer. His problems grew worse after his wife’s death in 1901. His frequent and lengthy absences from the commons drew criticism, and in 1906 Laurier lost his patience. He wrote out in his own hand a pledge for Emmerson to sign that he would “never . . . again taste wine, beer or any other mixed or intoxicating liquor” and that he would provide the prime minister with an undated and signed letter of resignation to be used should he fail in his promise. The firm writing of Laurier is followed by the shaky signature of Emmerson.

His departure from the cabinet was not long delayed. It resulted from an angry debate that began in the commons on 19 Feb. 1907 and in which Emmerson was not directly concerned. Retaliating against charges that he was somehow involved in improprieties in insurance dealings, Conservative mp George William Fowler responded, “I shall allow no man to make an attack on me or my character without retorting. I shall discuss the character of hon. members opposite whether they be ministers or private members, and their connection with women, wine and graft.” A motion on 26 March by Henri Bourassa* for an inquiry into Fowler’s remarks was defeated. The next day James H. Crocket, managing director of the Fredericton Daily Gleaner, in which Fowler had a financial interest, named Emmerson as the individual to whom “women” and “wine” applied, describing him as “an intolerable reprobate” and claiming that he had been ejected from a Montreal hotel with two women of ill repute. Emmerson denied the charges but on 1 April he submitted his resignation, which Laurier accepted. His portfolio went to George Perry Graham*.

Emmerson took action against the Gleaner and other newspapers that had repeated its charges. In May Crocket was arrested on a charge of defamatory libel, but he was quickly released on bail. The trial began before Mr Justice Pierre-Amand Landry on 18 June, with the team for the prosecution headed by William Pugsley*. Landry declined to dismiss the case but allowed it to stand over until the January 1908 term of the court. On 26 June Emmerson told the press that the judge had decided “that it was in the public interest that statements such as that [of the Gleaner], whether true or false, should be published, providing the writer or publisher believed them to be true when published.” Emmerson claimed this stand “removed all consideration as to the truth or falsity of the allegation” and made it useless to continue the case, Crocket “being entitled to acquittal under any statement of the facts.” The case was dismissed the following year.

Although attempts by Emmerson’s friends to obtain public appointments for him failed, he continued to play an active role. An mp for seven more years, he capably represented the interests of the Maritimes in general and New Brunswick in particular. He continued, for example, to press for the amalgamation of branch lines with the ICR and to promote the extension of the Intercolonial to the Great Lakes, either by construction or by the acquisition of running rights over existing lines. Described by the Saint John Globe as “an able speaker and powerful in debate,” he was something of a parochial politician and his potential was not fully realized because of his problems with alcohol. A Liberal in both English and Canadian politics, he was a great admirer of Gladstone and of Edward Blake. Provincially, he contributed to the evolution of the modern Liberal party from the Liberal and Liberal-Conservative coalition of the late 19th century.

Emmerson died on 9 July 1914. Upwards of 10,000 people lined the streets in Moncton for his funeral. The president of Acadia University preached the sermon, taking as his text, “He was a man.” A governor of Acadia, to which he had donated money for the Emmerson Memorial Library and from which he received an honorary ma, he had been president of the Baptist Convention of the Maritime Provinces in 1899 and of the Baptist Congress of Canada in 1900. None of the New Brunswick daily newspapers, including the Gleaner, mentioned in his obituary his resignation from the federal cabinet or its cause.

NA, MG 26, G. Daily Transcript (Moncton, N.B.), 7 Feb., 15 Dec. 1887; 21 July 1898. J. E. Belliveau, The Monctonians (2v., Hantsport, N.S., 1981–82). Biographical review . . . of leading citizens of the province of New Brunswick, ed. I. A. Jack (Boston, 1900). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1888, 1900–14. Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1901–14. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Canadian who’s who (1910). A. R. Clark, “The Intercolonial: its influence on Canadian development” (ma thesis, Acadia Univ., Wolfville, N.S., 1953). CPG, 1888–1914. J. R. Emmerson, History of Westmorland County; Emmersons and descendants (n.p., [1975?]). R. E. Garland and L. G. Machum, Promises, promises . . . an almanac of New Brunswick elections, 1870–1980 (Saint John, 1979). Sandra Gwyn, The private capital: ambition and love in the age of Macdonald and Laurier (Toronto, 1984). N.B., House of Assembly, Synoptic report of the proc., 1888–92, continued by the unicameral Legislative Assembly, 1893–1900. Prominent people of New Brunswick . . . , comp. C. H. McLean ([Saint John], 1937). Joseph Schull, Laurier, the first Canadian (Toronto, 1965). O. D. Skelton, Life and letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (2v., Toronto, 1921), 2. Elspeth Tulloch, We, the undersigned: a historical overview of New Brunswick women’s political and legal status, 1784–1984 (Moncton, 1985). C. A. Woodward, The history of New Brunswick provincial election campaigns and platforms, 1866–1974 . . . (1v. and microfiche, [Toronto], 1976).

Cite This Article

Wendell E. Fulton, “EMMERSON, HENRY ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/emmerson_henry_robert_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/emmerson_henry_robert_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Wendell E. Fulton |

| Title of Article: | EMMERSON, HENRY ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2024 |