BARTHE, ÉMILIE (baptized Marie-Louise-Émilie) (Lavergne), woman of the world; b. 26 March 1849 in Montreal, daughter of Joseph-Guillaume Barthe*, clerk of the Court of Appeal of Lower Canada, and Louise-Adélaïde Pacaud; m. 29 Nov. 1876 Joseph Lavergne, a lawyer, in Arthabaskaville (Victoriaville), Que., and they had one son and one daughter; d. 10 May 1930 in Montreal.

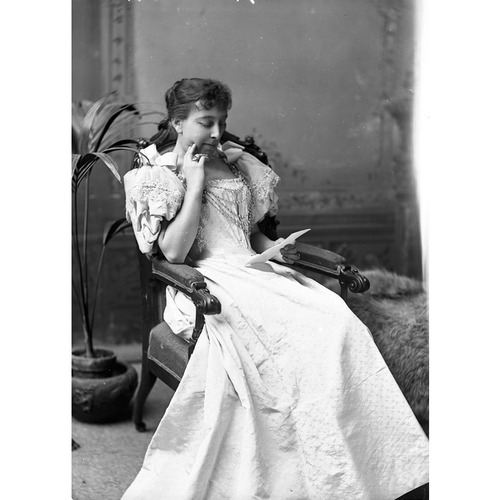

Émilie Barthe was the fourth child in her parents’ household, and it was soon clear that she would be as colourful, original, and talented as her father and uncles before her – including the famous Pacaud brothers, Édouard-Louis* and Philippe-Napoléon*. By the time she was four, she was living with her family in Paris, where it is thought that the Barthes were on visiting terms with such celebrities as Alphonse de Lamartine. Émilie’s schooling began on her return to Lower Canada in 1855. Depending on her father’s various postings, she studied initially with a tutor in Trois-Rivières, and then with the Ursuline sisters in Quebec City from 1 Oct. 1857 to 7 July 1862. After 1862 she probably continued to work for a couple of years with a tutor in Quebec City and between 1865 and 1869 she pursued her education in the Lévis region. By this point, Émilie Barthe had become a lively and witty young woman, a bilingual anglophile with cutting repartee and infectious cheerfulness. Although not herself a beauty, she had learned to appreciate beautiful things, fine clothes, English manners, and social gatherings. Ambitious, eager to reach new heights, and already highly cultured, she found great pleasure in reading widely – aside from the company of learned men, it was her chief interest.

It was at Arthabaskaville, from 1876, that Émilie Barthe shaped her future, for there, in the same year, she married Joseph Lavergne, a hard-working if rather lacklustre lawyer who was a partner of Wilfrid Laurier*. Although she had lived in Detroit around 1874–75, Émilie was happy in Arthabaskaville, where she had recently moved. In 1877 she gave birth to Gabrielle and in 1880 to Armand [La Vergne*], one of the future leaders of Henri Bourassa*’s Canadian nationalist movement, who, even as a child, was brought into the world of books and the arts by his mother. Émilie lost no time in winning over the leading citizens of the place who, besides visiting celebrities such as Louis Fréchette* and Hector Fabre*, included lawyers, politicians, and artists, some of whom, like Laurier and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté*, were to become famous. Until 1897 the Lavergne home was the social hub of Arthabaskaville, where people gathered to enjoy fine cuisine and discuss Liberal politics, literature, and history, often to the accompaniment of music and singing. Émilie was an outstanding hostess. In the finery of her Parisian gowns, dutifully paid for by Joseph (though he could not manage to make ends meet), she reigned over her modest little realm. Her life was further brightened by visits to Murray Bay (La Malbaie) and by travel, with, for example, trips to Old Orchard Beach in Maine in 1888, New York in 1892, and Boston in 1894. In this period she also aspired to broaden her horizons and explore other worlds where her talents as a leading light in society would be appreciated. To this end, she developed special relationships with Premier Honoré Mercier* and with Edward Blake*, who had been leader of the Liberal party. But it was Laurier who would show her the royal road ahead.

Émilie and Wilfrid had admired one another from 1876. They had the same literary interests, the same love of things English, the same desire to outdo themselves, and the same sensitivity. This mutual attraction grew into love and became the most celebrated liaison in Canadian political history. This woman, who would never have any official status, so captivated Laurier that at times, openly and with the full knowledge of their spouses, Zoé and Joseph, she was his confidante, go-between, and éminence grise. Already an established fact in 1878, the liaison became more intense in the 1880s and gave rise to a steady exchange of letters, at least at the beginning of the next decade. Émilie, whose library contained the volume of the collected Lettres de Adrienne Le Couvreur published by Georges Monval in Paris in 1892, was apparently the instigator of this correspondence. The 41 letters from Laurier discovered in 1963 by historian Marc La Terreur, which were written for the most part in English between 1891 and 1893, reveal the intimacy of their relationship. (Émilie’s side of the correspondence has not, thus far, come to light.) Tender thoughts about Gabrielle and Armand are shared, as well as views on politics, religion, philosophy, and history. Opinions about literature in its many forms are also exchanged, though Émilie – whom Laurier compared to Mme de Staël and urged to become a writer herself – preferred historical biographies. In these letters, Laurier kept Émilie abreast of the undercurrents of politics in Ottawa, and in the summer of 1891 he made skilful use of her as a go-between in his dispute with Edward Blake over the issue of unrestricted commercial reciprocity with the United States. The opinions and advice she sent him helped transform Laurier into a sophisticated statesman. For his part, he at last would find the words to express his love openly, as in this letter of 23 Aug. 1891: “I would like to see you, my dear, dear, friend, not to have your explanations, but simply to see you, to hear you, to look in your eyes, to listen to your voice, to feel that it is you, to be sure of it, to enjoy the consciousness of it.” Their love gave rise to gossip: some said that Laurier was the father of young Armand, who looked so like him. The letter writers, apparently, did not really care: they knew their love was “right,” as Émilie would later declare.

Having become prime minister, Laurier exulted in this letter of 30 Sept. 1896: “How I long to see you in a milieu . . . more worthy of you.” On 4 Aug. 1897 he appointed Joseph Lavergne, who until then had been an mp, a judge of the Superior Court for the district of Ottawa. The flamboyant Émilie lost no time in making her presence felt in the capital, organizing dazzling receptions, involving herself in charitable endeavours, and attending official dinners. However, at some point between 1899 and 1901, her star began to wane. Realizing the damage that the rumours about their relationship might cause, Laurier returned her letters to her and increasingly distanced himself from her. In addition, he moved her husband from Ottawa to Montreal in 1901. Henceforth it was through Joseph, Armand, or Gabrielle that he would send her his “best wishes.” Émilie understood, but she would never be the same and never forgot Laurier, as her later correspondence with, for example, the librarian and historian Alfred Duclos De Celles reveals. Thus began what she referred to as her “dull years,” during which she kept up certain social appearances in Montreal and Saint-Irénée (her summer residence). On 9 Jan. 1922 Joseph Lavergne died. On 15 Oct. 1924, at the age of 75, Émilie moved into the Foyer Saint-Mathieu of the Grey Nuns of Montreal, where she would spend the rest of her days. She lived as a recluse, sadder and lonelier than ever, always complaining about the lack of money and deeply affected by the loss of her daughter, Gabrielle, who died in 1928. It was then that she gave Laurier’s 41 letters to her nephew, perhaps as a way of leaving her name attached to the man she had loved so deeply.

Émilie Lavergne died peacefully on 10 May 1930 and was buried in Arthabaska (Victoriaville). Described in 1903 as the most brilliant society woman in French Canada, she was a mondaine fitting for an exceptional period of Canadian history.

[The Émilie Barthe Lavergne collection, held at the LAC, MG 27, I, I42, contains little information aside from copies of the 41 famous letters that Wilfrid Laurier wrote to her and some other correspondence. The author has a personal archival collection concerning the Lavergne family, including several unpublished letters written or received by Émilie, Armand, and his wife Georgette (née Roy), photographs, and a number of books, which offer remarkable insight into the private life of Émilie Barthe Lavergne. Among other useful collections are the papers of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (LAC, MG 26, G), Edward Blake (AO, F 2, mfm. at LAC), Armand La Vergne (LAC, MG 27, II, E12 and ANQ-Q, P487), and Ernest Pacaud (LAC, MG 29, D36). Worth mentioning as well are ANQ-M, CE601-S51, 29 mars 1849; ANQ-MBF, CE402-S2, 29 nov. 1876; Arch. des Sœurs Grises (Montréal), Foyer Saint-Mathieu, caisse recettes et déboursés, 1923–31; and Arch. du Monastère des Ursulines (Québec), Fonds de l’éducation, fichier des anciennes élèves; prospectus. The newspaper L’Union des Cantons de l’Est (Arthabaska [Victoriaville], Qué.), read for the period 1876–97, also provides interesting information.

There are no books or in-depth articles devoted exclusively to Émilie Barthe Lavergne. There are, however, some other articles and chapters, or excerpts, in books that concern her, especially the question of her relationship with Laurier: H.-A. Bizier, Histoires d’amour ([Montréal], 1987), 29–32; [Sir Wilfrid Laurier], Dearest Émilie: the love-letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier to Madame Émilie Lavergne, intro. Charles Fisher (Montreal, 1991); Sandra Gwyn, “The lady who loved Laurier,” Saturday Night, 99 (1984), no.8: 18–26 and The private capital: ambition and love in the age of Macdonald and Laurier (Toronto, 1984), 243–72; Madeleine [A.-M]. Gleason-Huguenin, Portraits de femmes ([Montréal], 1938), 181; Types of Canadian women . . . , ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1903); Marc La Terreur, “Correspondance Laurier–Mme Joseph LaVergne, 1891–1893,” CHA, Report (1964): 37–51 and “Sir Wilfrid Laurier écrit à Émilie Lavergne,” Le Magazine Maclean (Montréal), 6 (1966), no.1: 14–15, 36–39, 41; [Armand La Vergne], Armand Lavergne, ed. Marc La Terreur (Montréal and Paris, 1968), and Trente ans de vie nationale (Montréal, 1934); and [Renaud La Vergne], Histoire de la famille Lavergne, comp. B. C. Payette (Montréal, [1970]). Le Devoir, 10 mai 1930, contains a very brief obituary. r.b.]

Cite This Article

Réal Bélanger, “BARTHE, ÉMILIE (baptized Marie-Louise-Émilie) (Lavergne),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barthe_emilie_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barthe_emilie_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Réal Bélanger |

| Title of Article: | BARTHE, ÉMILIE (baptized Marie-Louise-Émilie) (Lavergne) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |