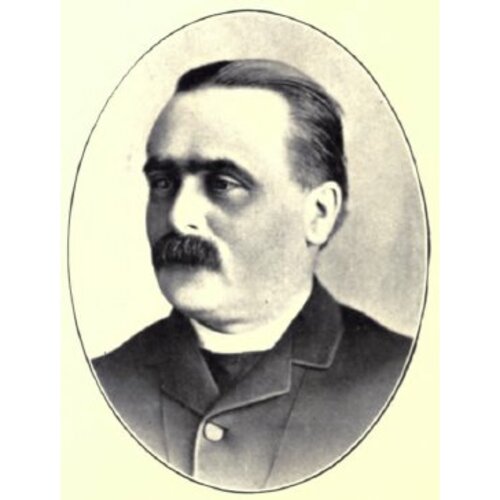

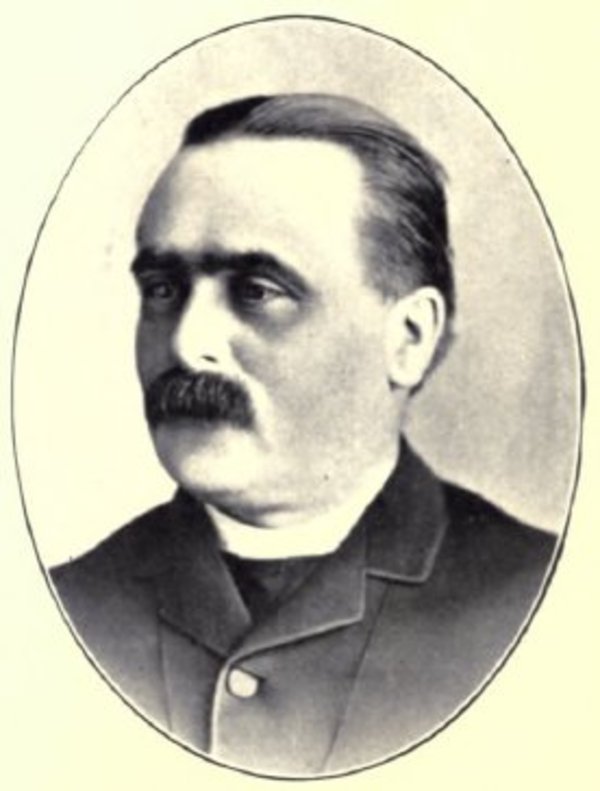

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ÉVANTUREL, FRANÇOIS-EUGÈNE-ALFRED, lawyer, civil servant, office holder, politician, and journalist; b. 31 Aug. 1846 at Quebec, son of François Évanturel*, a lawyer, and Louise-Jeanne-Eugénie Huot; m. there 3 June 1873 Maria Victoria Louisa Lee, and they had a daughter and a son; d. 15 Nov. 1908 in Alfred, Ont.

Alfred Évanturel studied at the Petit Séminaire de Québec and at the Université Laval, where he received his llb in 1869. He was called to the bar two years later. Before his marriage he practised law briefly in Quebec City, but he moved with his wife to Ottawa to take up a position in 1874 in the secretariat of the minister of public works. There he began his long career in public life, including work with the Institut Canadien-Français and the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. From 1874 to 1876 he was school trustee for Wellington Ward. Recognized as a gifted speaker, he was invited to events throughout the Ottawa valley. One trip in 1880 brought him to Prescott County, in the francophone region of eastern Ontario, where he addressed the inaugural celebration of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste at L’Orignal. After a short time in the Post Office Department, he left the civil service and moved with his family in 1881 to the small village of Alfred, the most exclusively francophone community in the province. Évanturel soon began promoting the view that French Canadians throughout Ontario had a common identity, one that was related as much, or more, to residence in Ontario as it was to associations with Quebec society.

Évanturel later explained that he had moved to Alfred in particular because of his perception that the large francophone population of Prescott County was severely disadvantaged in Ontario’s legal system. Perfectly bilingual, he intended not only to act as a translator for his clients in the English-language courts but also to explain the legal system to them. After two years he claimed great success in achieving those aims.

The legal plight of francophones in Ontario was recognized by Évanturel as only part of the experience of the linguistic minority, and his ambitions as a lawyer soon grew into the greater goal of representing Prescott in the Ontario legislature. In 1883 he gained the Conservative nomination there but lost the election by a small margin. This election exposed the mounting tension between anglophones and francophones at both the local and provincial levels. The question of language of instruction in schools became the focus of a conflict in which the Conservatives championed an English-only policy. This position, combined with Conservatives’ support for the hanging of Louis Riel*, had completely alienated Ontario’s francophones by the time of the 1886 election. Évanturel now presented himself as a Liberal although he was opposed by another Liberal candidate, who sought the anglophone vote. He won and would hold the seat until his defeat, by another francophone, in 1905.

In 1886 Évanturel became editor-in-chief of a new weekly newspaper in Alfred, L’Interprète, founded to contribute further to the ability of francophones to function effectively in Ontario. In the debate about French-language schooling it responded to attacks on the French Canadian population by such anglophone newspapers as the Toronto Daily Mail, which sent investigative reporters to Prescott County [see Christopher William Bunting*]. Under Évanturel L’Interprète became a major forum for expressions of francophone affirmation in eastern Ontario, and it attracted considerable attention outside Prescott. In 1892 Henri Bourassa* purchased the journal and moved it across the Ottawa River to Montebello.

Although Évanturel became well known, he never achieved fame and has not been considered by historians as a major figure in Ontario politics. Part of the explanation lies in his attitude and actions after he became an mla. Within Prescott he spoke aggressively about the need to defend francophones in Ontario. However, in the legislature he was notably quiet; his few remarks never went beyond the cautious statements of his anglophone Liberal colleagues led by Oliver Mowat. He thus became useful to the Liberals, who were able to benefit from his name without feeling pressure to alter their policies toward francophones. While the Conservatives argued for a coercive approach to assimilation, the Liberals adopt-. ed a more patient, conciliatory means to the same end. Francophones supported the Liberals as the lesser evil.

Évanturel was quite willing to play the role of a loyal party member, but he expected to profit personally from his quiescence and his hard work for other Liberal candidates during campaigns. Soon after entering the legislature, he began applying pressure to enter the cabinet because he was a francophone and because he was Catholic. Emphasizing that minorities must be represented in the Ontario cabinet, just as anglophones were in the Quebec cabinet, he claimed that he would be supported by both francophones and Irish Catholics. During the early 1890s he combined threats to leave provincial politics with letters to Liberal leaders, including federal leader Wilfrid Laurier*.

Events in the 1890s worked in Évanturel’s favour, especially as the Manitoba school question moved to the centre of national attention [see Thomas Greenway]. Elected prime minister in 1896 and embroiled in this controversy, Laurier came to see the logic of Évanturel’s thinking. In late 1896 he began to put considerable pressure on his Ontario counterpart to find room for tvanturel as a way to enhance Liberal support at both the federal and the provincial levels. In December he wrote to Premier Arthur Sturgis Hardy to explain that, “from the point of view of Dominion politics, such a step . . . would be an offset to the School question in showing the liberality of our Ontario friends to their French brothers.” The possible electoral consequences in Ontario for the federal government as a result of its handling of events in Manitoba loomed large in his mind: “The selection of Évanturel would in all probability, secure the French vote absolutely.”

Hardy was not initially receptive to Laurier’s argument. The provincial Liberals recognized that they had nothing to gain (since they were already receiving the francophone vote) and much to lose (in the form of anglophone outrage) if they gave more prominence to Évanturel. However, Laurier’s sustained intervention led the Ontario government to appoint Évanturel as speaker of the Legislative Assembly. He served in this position from 1897 to 1902, earning the respect of both Liberals and Conservatives; the Toronto Globe later described him as “one of the best Speakers that ever presided over the deliberations of the Legislature.” In the cabinet shuffle of November 1904 he was made a minister without portfolio, a post he held until he was defeated, along with the government, in the election of January 1905. He was thus Ontario’s first francophone speaker and cabinet minister.

After his defeat, Évanturel wrote to Laurier in hopes of receiving an appointment as a senator or to some other prestigious federal position. By March 1906 he had become frustrated and somewhat bitter as these hopes remained unfulfilled. He complained to the prime minister that he had the sense of having “lost everything” and being “the only man in public life who in 25 years in politics did not receive or ask for anything.” His appointment in December 1907 to a clerkship in the Senate provided some compensation. Less than a year later Évanturel died. Remembered for his skills in oratory and journalism and as speaker of the legislature, he was survived by his daughter, Stella, and son, Gustave, later an mla and advocate of bilingualism in Ontario schools.

A speech by Alfred Évanturel on French-language schooling was published in Report of the speeches delivered by Hon. Mr. Mowat, Hon. Geo. W. Ross, Mr. Evanturel, m.p.p., in the Legislative Assembly, April 3rd, 1890, on the proposed amendments to the School Act in relation to the use of the French language in the public schools (Toronto, 1890). A copy of his printed leaflet, “Aux Canadiens français du comté de Prescott,” dated L’Orignal, Ont., November 1883, is preserved in the Arch. de l’Archidiocèse d’Ottawa.

ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 1er sept. 1846, 3 juin 1873. AO, RG 22, ser.353, no.1427. AUL, U-506/36/4/E–F. NA, MG 26, G: 9605–6, 10403–4, 108212–15. Globe, 23 Nov. 1904. News and Ottawa Valley Advocate (L’Orignal), 22 June 1880, 31 July 1883. Can., Senate, Journals, 1907/8: 37, 513. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Directories, Carleton County, Ont., 1886/87, 1895; Ottawa, 1874/75: 193; Quebec, 1872/73. Kathleen Finlay, Speakers of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, 1867–1984 (Toronto, 1985), 38–40. Chad Gaffield, Language, schooling, and cultural conflict: the origins of the French-language controversy in Ontario (Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1987), 131–52. Ont., Chief Election Officer, Hist. of electoral districts (1969). P.-F. Sylvestre, “Les joumaux de l’Ontario français, 1858–1983,” Soc. Hist. du Nouvel-Ontario, Doc. hist. (Sudbury, Ont.), no.81 (1984), 24.

Cite This Article

Chad Gaffield, “ÉVANTUREL, FRANÇOIS-EUGÈNE-ALFRED,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/evanturel_francois_eugene_alfred_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/evanturel_francois_eugene_alfred_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Chad Gaffield |

| Title of Article: | ÉVANTUREL, FRANÇOIS-EUGÈNE-ALFRED |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |