Source: Link

RAYSIDE, EDITH CATHERINE, nurse; b. 26 Jan. 1872 in Martintown, Ont., fifth of the eight children of James Rayside and Margaret McDougall; d. unmarried 20 Dec. 1950 in Lancaster, Ont.

Edith C. Rayside’s family was prominent in Glengarry County by the time her parents settled, around 1880, in what would become known as South Lancaster, a landing point on the St Lawrence River for many loyalist settlers in the late 18th century and a destination for immigrants from the Scottish Highlands. Her mother came from deep Glengarry roots, and her father, who represented the county as a Liberal in the provincial legislature from 1882 to 1894, built an extensive lumber business in the area. Inkerman Cottage was the handsome brick house they moved into, named for a much-romanticized battle in the Crimean War, a conflict that made nursing leader Florence Nightingale famous.

The family’s economic standing allowed Edith to extend her education when few girls did, and the comparative proximity and Presbyterian affiliation of Queen’s University in Kingston made it a logical choice. She enrolled in 1890 and completed her ba in 1896, her graduation perhaps delayed by the illness and death, in 1895, of her father. She seems to have imagined becoming a schoolteacher, for she then spent a year at the School of Pedagogy in Toronto [see James Alexander McLellan*]. In 1898, however, she took a career-defining step by entering the nurse-training program at the newly constructed St Luke’s Hospital in Ottawa, where her studies were overseen by superintendent Annie Amelia Chesley*. Three-year hospital-based training programs were then proliferating in Canada, shaped by the professional standards associated with Nightingale and by models of “efficiency nursing” founded on scientific-management techniques. They had strict codes of conduct, including unquestioning deference to superiors. At the same time, nurses were expected to embody nurturing femininity, to have an unblemished moral character, and to be unmarried. While training in English Canada was formally separated from religious instruction, schools were thoroughly imbued with a sense of mission informed by Christian faith. All these factors enhanced the allure of nursing as a professional option for those who valued respectability and who recognized a role for middle-class women in social reform.

Rayside graduated in 1901 alongside six others in St Luke’s first cohort. Employment opportunities were scarce for the fewer than 300 trained nurses across Canada, and like most she began in private nursing, working in the homes of those who could afford to pay. In 1905 she obtained a position as visiting nurse with the Ottawa branch of the Canadian Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis. She resigned in September 1906 and subsequently took up a public-health opportunity in Indian Head, Sask., at a time when the need for district and school nurses in remote areas was receiving more attention; she returned to South Lancaster at the end of 1907.

At some point Hattie Megill (McGill), a former senior member of the St Luke’s nursing staff, asked Rayside to join her at a hospital in Mapimi, in north-central Mexico, an opening she took up in March 1909. The nearby Ojuela Mine was one of Mexico’s largest, and even if working in it was brutally arduous, its owner was unusual among mining companies in establishing a well-equipped hospital with fully trained nurses. Megill’s death in October 1910 seems to have thrust Rayside into the role of nurse superintendent. But revolutionary unrest, led by Francisco (Pancho) Villa, was intensifying in the area, a circumstance that may have convinced her to return home by early 1911, though her mother’s declining health was likely a more compelling consideration.

Margaret Rayside died that March, and sometime afterwards Edith resettled in Ottawa. There she obtained a nursing position at the May Court Club, which operated a clinic for those suffering from lung disease, part of a broader mandate to improve social services for disadvantaged women and children.

Within a few years, opportunities for trained Canadian nurses would open up dramatically. The British declaration of war against Germany in August 1914 automatically implicated Canada, and the government in Ottawa was immediately asked by the imperial authorities to supply a full division of 25,000 troops and five hospital units. The Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) had been established as the Permanent Army Medical Corps in 1904, soon after the South African War. In 1906, when the nursing service was made an integral part of the unit, the corps had two full-time female members, Cecily Jane Georgina Fane Pope* and Margaret Clotilde Macdonald. Women aspiring to join them were required to have graduated from a recognized training program, and in the face of stiff resistance within parts of the Canadian army, they would be given the rank and pay of officers. Canadian nurses faced a military apparatus intent on keeping them within defined female roles and subordinating those roles to the leadership of men. Still, they could boast of comprehensive training as well as pay rates higher than those of their colleagues in other countries, which earned them the label “Millionaire Colonials.”

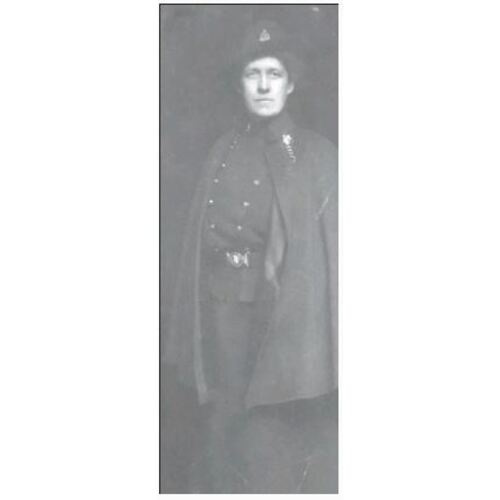

When war was declared, Margaret Macdonald was charged with recruiting and equipping nurses to accompany the troops. Her office was flooded with applications from the very start, and through the rest of the war the flow of volunteers never stopped. Some 100 of them, the forerunners of the more than 2,400 nursing sisters who would serve overseas in the CAMC, sailed for England with the first contingent in early October 1914. Rayside enlisted in January 1915. Her experience made her a prime candidate for a leadership position, and when she left Halifax in early February, it was as one of two matrons in charge of more than 70 nurses. In a letter to a friend in December that year, she would dismiss praise for her work as a matron by saying that she had never sought the appointment and that when asked to assume the role, she admitted her utter lack of preparation for it.

Rayside would soon head the nursing corps of No.2 Canadian General Hospital (CGH), which had been formally constituted in the fall but was lingering in England while awaiting transfer to France. In March the order finally came to locate No.2 on a plateau above the coastal resort town of Le Tréport, in an exposed position overlooking the English Channel. The Canadians were to create and staff a hospital initially made up entirely of tents and having an eventual capacity of 1,040 beds, with Rayside supervising around 70 nursing sisters.

As the staff ramped up to full capacity through April, large numbers of patients flooded in, including victims of fierce fighting at Ypres (Ieper), Belgium [see Sir Arthur William Currie*]. In early May the first victims of gas poisoning arrived, and on the night of the 18th the hospital received 537 sick and wounded, applying an efficient patient-intake system that would soon be adopted by other hospitals. Medical personnel were now facing horrendous wounds and serious illness – according to Rayside, “too awful for words” – for which civilian work at home would have provided only modest preparation. Among the patients, Canadians were “perhaps” given special treatment, Edith admitted to a correspondent: “I know I find myself slipping them little favors on the Q.T.”

Canadian hospitals were organized within command structures that were largely shaped by the British, but the Canadian government insisted on some independent leadership for units attached to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Rayside’s Canadian matron-in-chief was Margaret Macdonald, based in London; while in France, however, Rayside also reported to Emma Maud McCarthy, the British matron-in-chief for France and Flanders. Adding to the complexity was the subordination of nurse leadership to military commanders, who were capable of moving medical personnel, and entire hospitals, without consultation.

Rayside’s job was made more difficult still by the constant transfer of nurses. Macdonald wanted to provide them with varied experience, including time in highly coveted postings at casualty clearing stations adjacent to the front lines. The British also shuffled personnel to staff their own medical units, responding to new battle strategies or casualty patterns. Nurses themselves often sought positions near to loved ones at the front or to nursing colleagues with whom they had developed especially close ties.

Soon after No.2 was fully operational, Rayside had secured the appointment of Elizabeth Lawrie Smellie*, who had sailed with her in February, as night supervisor and superintendent of the hospital’s medical section (as distinct from surgical). They would remain administrative colleagues until their demobilization, and friends for the rest of Rayside’s life.

By the end of September 1916, when Rayside’s time as matron of No.2 was coming to a close, the hospital had admitted over 23,000 patients. This influx represented an immense administrative challenge, stretching nurses to the limits when convoys arrived and the staff tried to maintain the standards required to prevent dreaded infection, often in the midst of rain-soaked terrain and winds strong enough to blow tents down. Large battles, even when the British, French, and Canadian troops were successful, produced waves of casualties, and space had to be made available by evacuating moveable patients to England with little warning. Slow periods presented a different challenge in managing boredom, though hospitals regularly organized concerts, theatrical productions, and other social activities.

Rayside received word on 5 Oct. 1916 of her transfer to a large military base at Shorncliffe in southeast England. Moore Barracks Hospital there had been established to serve Canadian and British troops awaiting relocation to France and to receive sick and wounded soldiers evacuated from hospitals in European and other war zones. By the time of Rayside’s reassignment it was also being used as a training ground for CAMC staff, so that personnel transfers became an even more constant feature of life than they had been at No.2 CGH. She arrived during a period when a spotlight was being shone on the treatment of Canadian wounded in England [see Guy Carleton Jones], one consequence of which was an expansion of Moore Barracks Hospital.

Rayside served there until June 1917, when she was attached for instructional purposes to the office of the Canadian director general of medical services in London, where she worked alongside Matron-in-Chief Macdonald. In July she accompanied Macdonald on an inspection tour in France, but in the following month she was told to report to military headquarters in Ottawa. There she was appointed matron-in-chief of military nurses in Canada, a newly created, and at first only temporary, position. By the time of her return, there were over 60 military hospitals in Canada, with a total capacity of more than 12,000 beds and a staff of around 500 nurses. This vast network was to be an immense challenge for Rayside’s office, augmented by the responsibility for selecting nurses still volunteering in large numbers for overseas service, and doing so in a way that avoided favouritism. What turned out to be the final year of the war was also its deadliest. Military hospitals in Europe and Canada had to cope with the treatment and convalescence of thousands of soldiers with physical and mental wounds, and with the firestorm of deadly sickness created by the influenza pandemic that raged in 1918–19. It would not be until mid 1920 that Rayside, along with many others, was demobilized.

In November 1915 Rayside had been mentioned in dispatches “for gallant and distinguished service in the field.” Two years later, in February, she was awarded the Royal Red Cross, 1st class, a British honour created for military nurses in 1883. She tended to downplay such recognition and would have agreed with a Canadian nursing sister who later commented that she was “just there to do a job and I did it.” But Rayside and her nursing colleagues were clearly proud of being able to attach rrc to their names.

In early 1919 Rayside was elected by the alumni of her alma mater as the first female member of the Queen’s University board of trustees. On 11 November of that year the University of Toronto held a special convocation to recognize Canadian military leaders, and she became the first woman to be given an honorary degree by that institution. The degree conferred by Chancellor Sir William Ralph Meredith*, however, was an honorary master’s of household science. As her good friend Charlotte Elizabeth Hazeltyne Whitton* would remark years later, “It would be hard to conjure up anything more incongruous than the upright, majestic Edith Rayside in military uniform moving forward to be given a degree, implying an award for women’s service within the home.” Rayside’s response reportedly was, “They’ll get used to us.”

The wartime contribution of Canada’s military nursing corps enhanced the professional standing of nurses beyond demobilization. Although employment prospects in hospitals for those who had served and those coming out of nurse-training programs were diminished, there were other opportunities in social work and public health. Many wartime gains women had achieved in accessing reasonably paid work were reversed after the hostilities ended, but a few new fields were available to them, and more generally, the post-war years were an age of increasing women’s advocacy for social and political change.

Awaiting demobilization, Rayside prepared for civilian work by taking a course in hospital administration at New York’s Columbia University. In the fall of 1920 she secured a position in theoretical nursing (differentiated from practical training) as one of two instructors in the Montreal General Hospital’s Training School for Nurses [see Gertrude Elizabeth Livingston*]. She arrived just as McGill University was creating, under director Flora Madeline Shaw*, its School for Graduate Nurses, which offered an eight-month program to provide a grounding in public-health nursing, a rapidly expanding field, and to enhance nurses’ preparedness for teaching and administration. She undoubtedly applauded the creation of this additional opportunity for continuing education in her field.

While teaching, Rayside fostered networks among trained nurses, and at her call in 1921, 23 CAMC veterans formed the Montreal Association for Overseas Nursing Sisters, electing her as their first chair. Twelve years later she would become president of the Overseas Nursing Sisters’ Association of Canada, soon after the national organization was formed. In 1921 she also attended a joint convention of the Canadian National Association of Trained Nurses (CNATN) [see Mary Agnes Snively*] and the Canadian Association of Nurse Education. Over the next two decades she remained active in the Canadian Nurses’ Association, which emerged from the CNATN in 1924.

In 1924 Rayside returned to Ontario when she was recruited as nurse superintendent by the Hamilton General Hospital, which viewed her acceptance as enhancing the prestige of its nurse-training program. She oversaw an important expansion in the program during a period when the hospital itself was growing in scale and reputation. One student recalled that she was “a firm disciplinarian” but “always fair and just, with a keen sense of humour.”

At the decade’s end, Rayside’s position entangled her in proposals for a reorganization of the hospital and its affiliation with McMaster University, some elements of which would marginalize nurse leadership in decision-making at Hamilton General. The difficulties she faced constituted one more example of a medical world dominated by men resisting the intrusion of professional women into their domain except as helpmates. This was also a time when the Great Depression was intensifying concerns about the lack of opportunities for trained nurses. Rayside proposed to the hospital governors in 1932 that graduate nurses be placed on a three-month rotation system so all would have some employment, but nothing appears to have been resolved during her superintendency.

Meanwhile, Rayside took time to honour her comrades from the war. In 1920, as matron-in-chief, she had attended the unveiling in the Montreal General Hospital of a plaque in memory of two of its graduates who had perished when the hospital ship Llandovery Castle was torpedoed in 1918 [see Rena Maude McLean*]. Six years later she was present at the unveiling of the memorial to fallen Canadian nursing sisters in the Hall of Honour of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. In 1927 she was back in the capital, in the Peace Tower at the centre of Parliament Hill, having been asked to represent Canadian nurses at the dedication of the Altar of Sacrifice in the Memorial Chamber, a ceremony attended by the Prince of Wales and many dignitaries from Canada and Britain. She stood at one of the four corners of the altar, which held the Book of Remembrance. It would eventually be inscribed with the names of the 47 nurses and tens of thousands of soldiers who had lost their lives in the Great War.

In 1931 Rayside learned that she had a brain tumour, and her medical colleagues helped get her to specialist surgery in Boston that saved her life. She returned to work in 1932, but glaucoma was now reducing her vision enough to force her resignation at the end of 1933, a decision that provoked a tide of affectionate and respectful tributes. She could still see well enough to attend a 1940 reunion of Hamilton General Hospital graduates marking the training school’s 50th anniversary, at which she received a “tremendous ovation.”

In early 1934 Rayside was named a commander of the Order of the British Empire (civil division). (The appointment came in the midst of the prime ministership of Richard Bedford Bennett, who restored the practice of sending Canadian names to London for incorporation in the royal honours list.) She was reported by Toronto’s Mail and Empire as saying that she could not understand why she had been singled out. Among the six other Canadians awarded the cbe that year, all women, were her friends Charlotte Whitton, honoured for her advocacy of child welfare, and Beth Smellie, now chief superintendent of the Victorian Order of Nurses and destined to follow in Rayside’s steps by serving as matron-in-chief of Canada’s military nurses in the Second World War.

Soon after her retirement, Rayside settled in South Lancaster. There she took up residence, only a few blocks from her childhood home, with the Reverend John Ulric Emmanuel Frederick Tanner, the husband of her sister Janet, who had died the previous September. When Tanner remarried, she moved to the larger village of Lancaster to live with another sister, Isabella McGillis, and her family. Charlotte Whitton visited Rayside in September 1948, at which point she was very deaf and almost blind, and some of what Whitton recalled from this last encounter appeared in the affectionate obituary she would pen two years later. The end came on 20 Dec. 1950, when Rayside was 78. John Tanner presided over her funeral on the 22nd. Beth Smellie, whose picture Rayside kept on her dresser for many years, was in attendance. She was buried in South Lancaster’s Presbyterian cemetery.

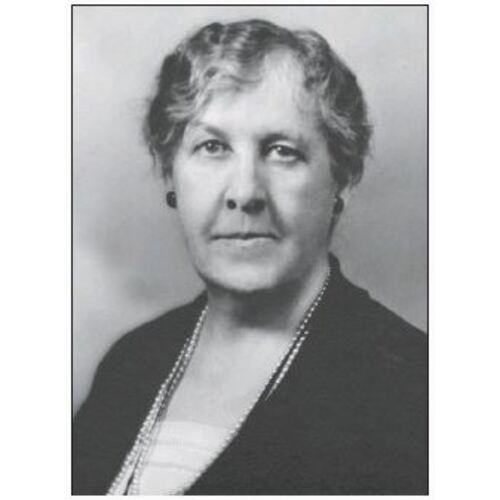

Whitton’s obituary described Rayside as “every inch the Matron-in-Chief” – “unusually tall [she was almost 5 feet 10 inches], of massive, noble build” – but also as “a gentle woman, quiet and soft-spoken.” She cited her deep religious faith and her serenity in confronting physical affliction, quoting her as reflectively asking, “Have I not seen in one life-time more than many others in several spans of years?” Rayside had remained single: like many of her colleagues in the Great War, she may have seen herself as beyond the marrying age once she was demobilized. She also craved challenge and independence, and probably found the prospect of family domesticity unappealing. She was content to enjoy the close friendship of strong women who shared a commitment to community welfare.

Rayside never acquired the forceful public profile that gave her colleague Margaret Macdonald and her friends Charlotte Whitton and Beth Smellie such prominence. She was unassuming, avoided the limelight, and deflected high praise. She was, however, disciplined and resilient even in dreadful circumstances. With quiet good humour she fought to enhance the educational standards and professional appreciation of nurses – and, whether she would agree or not, helped advance the recognition of women’s place beyond the strict gender boundaries of her day.

Arch. of Ont. (Toronto), F 895-1-0-174 (Letter from Edith Rayside, 8 Dec. 1915). Can., Dept. of National Defence, “Record of service – Overseas Military Forces of Canada medical units,” No.2 Canadian General Hospital: www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/military-history/history-heritage/official-military-history-lineages/ledgers/ww1-medical-units.html (consulted 17 Aug. 2020). Hamilton Civic Hospitals, School of Nursing Alumnae Arch. (Ont.), School of Nursing historical, box 14, acc. 2001.7.1.19 (autobiographical summary in Edith Rayside’s hand). Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), MG25-I248, vol.160 (Canadian Nurses Association fonds, Biog. files), Rayside Edith C.; RG9-III-B-2, vol.3678, file 29-11-1, file pt.[1–5] (Personnel, nursing services), memoranda from Edith Rayside, 18 Oct. 1917, 19 Dec. 1918; vol.3687, file 30-4-2, file pt.1 (General corr. – No.2 General Hospital), 4 Sept. 1915 (Routine of admission of patients); RG9-III-D-3, vol.5034, file 852, mfm. T-10924 (War diaries – 2nd Canadian General Hospital – commanding officer and matron diaries); RG 150, acc. 1992–93/166, box 8122-19. Private arch., David Rayside (Toronto), Archival files. Trent Univ. Arch., “Transcripts of Helen Fowlds’ World War I letters”: digitalcollections.trentu.ca/exhibits/fowlds/ftransclettpg.htm (consulted 12 Aug. 2020). Glengarry News (Alexandria, Ont.), 1907–11; 22, 29 Dec. 1950. Ottawa Citizen, 1905–6, 5 June 1915. J. K. [Bishop] Scott, A time to remember (1925–1928) (n.p., n.d.; booklet available at the Hamilton Civic Hospitals, School of Nursing Alumnae Arch.). Maureen Duffus, Battlefront nurses of WWI: the Canadian Army Medical Corps in England, France and Salonika, 1914–1919 (Victoria, 2009). Marjorie Freeman Campbell, The Hamilton General Hospital School of Nursing, 1890–1955 (Toronto, 1956). [Clare Gass], The war diary of Clare Gass, 1915–1918, ed. Susan Mann (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2000). Royce MacGillivray, Dictionary of Glengarry biography (Alexandria, 2010). Susan Mann, Margaret Macdonald: imperial daughter (Montreal and Kingston, 2005). K. [M.] McPherson, Bedside matters: the transformation of Canadian nursing, 1900–1990 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 2003). Mélanie Morin-Pelletier, Briser les ailes de l’ange: les infirmières militaires canadiennes (1914–1918) (Outremont [Montréal], [2006]). G. W. L. Nicholson, Canada’s nursing sisters (Toronto, 1975). On all frontiers: four centuries of Canadian nursing, ed. Christina Bates et al. (Ottawa, 2005). Cynthia Toman, Sister soldiers of the Great War: the nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (Vancouver and Toronto, 2016). War-torn exchanges: the lives and letters of nursing sisters Laura Holland and Mildred Forbes, ed. Andrea McKenzie (Vancouver and Toronto, 2016). C. [E. H.] Whitton, “An appreciation of Edith Rayside,” Queen’s Rev. (Kingston), 25 (1951): 10–12.

Cite This Article

David Rayside, “RAYSIDE, EDITH CATHERINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rayside_edith_catherine_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rayside_edith_catherine_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Rayside |

| Title of Article: | RAYSIDE, EDITH CATHERINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |