Source: Link

GASS, LELIA CLARE, nurse and medical social worker; b. 18 March 1887 in Shubenacadie, N.S., daughter of Robert Gass and Nerissa Miller; d. unmarried 5 Aug. 1968 in Halifax.

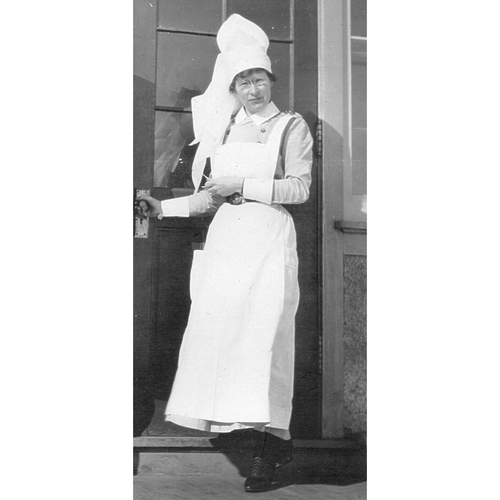

Nursing sister Lieutenant Clare Gass bought a record book in Montreal just as she was departing in 1915 for military training in Quebec City, on her way to war. By adjusting dates and filling in empty half-pages, she made it last for two of the four years she was overseas with the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC). In 1917 she replaced the original book with a more practical, pocket-sized diary, the pages of which precluded lengthy entries, and she would acquire a new one in 1918. Brevity and gaps characterize the tiny diaries as she moved closer to the front lines and as the war robbed her of family and friends. “Arrived Halifax Harbour 8 AM” is the last entry on 14 Dec. 1918. Clare Gass had returned safely to Nova Scotia; other CAMC nurses did not, including Agnes Florien Forneri* and Rena Maude McLean*.

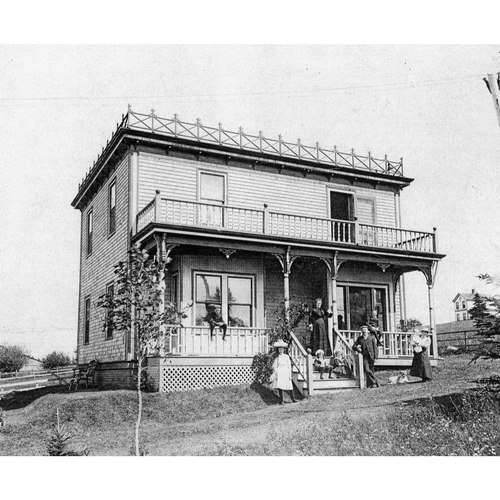

Her family home in Shubenacadie, about 40 miles north of Halifax, bore all the markings of small-town prosperity. Solid, spacious, with large windows and a double-decked front verandah, the house spoke of Robert Gass’s success as a general-store keeper and lumber-mill owner, and of his good fortune in marrying Nerissa Miller of the brick-making family across the river. As the eldest child and only girl in a family of ten (three of whom did not survive childhood), Clare was special to her poetry-loving father, and they were particularly close. For her, and only for her, he provided the sure stamp of middle-class status: four years of private secondary education. Clare attended the Church School for Girls, an Anglican institution in Windsor. There she acquired the knowledge, discipline, character, and perspective that took her easily into the hierarchical, regulated world of nursing training at the Montreal General Hospital, where she studied from 1909 to 1912.

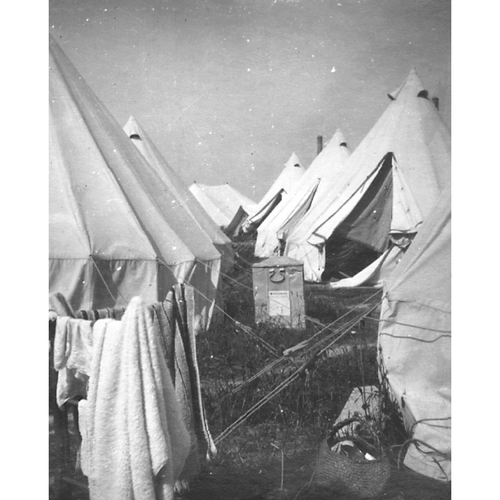

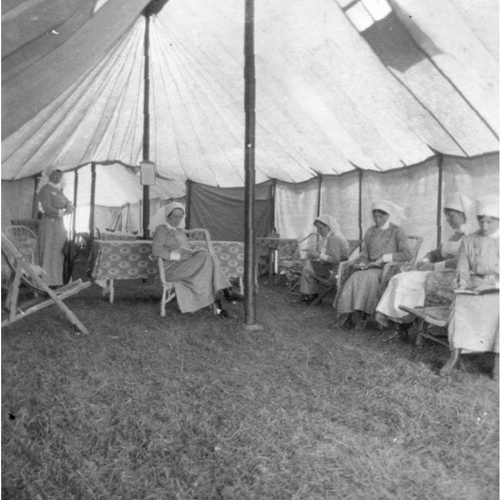

In April 1915, eight months after the First World War began, Gass left private nursing to become a nursing sister with No.3 Canadian General Hospital, which was fully staffed and equipped by McGill University. Except for short postings elsewhere and the occasional leave (to England or Scotland), Gass would spend most of the war years with the McGill unit. She knew many of her colleagues (among them physician and poet John McCrae*) from nursing-school days; the camaraderie so evident in her diary – teas, dances, masquerades, holiday festivities – was part of No.3’s esprit de corps. In the summer of 1915 she helped equip the wards of the initial, tented hospital at Camiers, on the north coast of France (at about the same time that fellow nursing sister Edith Catherine Rayside* was conducting similar operations at nearby Le Tréport). By the time the hospital moved later that year to more substantial quarters in a former Jesuit college just outside Boulogne, she had experienced her first taste of wartime nursing: “[the wounds] are too horrible. Can it be God’s will or only man’s devilishness?” (7 June 1915); “a big convoy … so many wounded & such tired men” (10 August); “our gas gangrene case died today” (17 September); “a great many head wounds – three lads died before they reached the wards” (26 September). Such comments became increasingly rare as she accustomed herself to the gruesome tasks. The work itself she enjoyed “if it were only possible to forget its cause” (2 March 1916).

Gass’s diary records hospital life at her various postings, including a visit from CAMC matron-in-chief Margaret Clotilde Macdonald* (9 September), and her own reaction to the arrival of new convoys of patients: how anxiously she searched for relatives and acquaintances. But when off duty, she delighted in the distractions of walking, cycling, sea bathing, picnicking, and touring – Peeps into Picardy in hand – in the surrounding countryside. Hers is a travel journal and a record of friendships as much as a diary of war. And when death touches her personally, she becomes very laconic indeed. After her brother Blanchard Victor and her second cousin Laurence Henderson (with whom she may have been in love) are killed within a day of each other at Vimy Ridge in April 1917, for example, Clare permits herself only a few words. She was more fulsome with poetry, which she transcribed at length – both her own and that of others, among them McCrae’s “In Flanders fields,” which she recorded six weeks before it appeared in London’s Punch magazine.

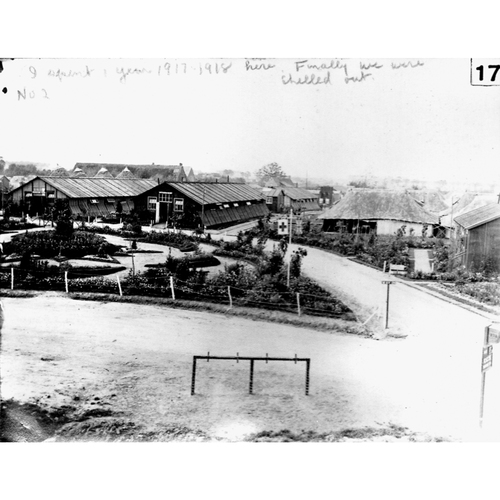

In November 1917 Gass obtained one of the short-term casualty clearing-station postings so coveted by many nurses. She thus moved much closer to the front lines, at Remy Siding in Flanders, Belgium, where she spent seven months at No.2 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station – a greatly expanded unit because of the length and nature of the war. There she had both day and night duty in medical, surgical, post-operative, and resuscitation wards. While at the clearing station, she “voted for the Union Government [see Sir Robert Laird Borden*] in Canada” (5 December), her status both as military personnel and as the female relative of soldiers having qualified her for the franchise. She also experienced the German offensive in the spring of 1918: “all patients evacuated this morning & we were called at noon & bundled off to St Omer in a hurry” (19 March); “our old hospital site at Remy is knocked to pieces” (5 May).

After two months back with her original unit, which itself experienced air raids through the summer of 1918, Gass was transferred to England in September to take on much lighter nursing assignments, followed by transport duty to Canada. While accompanying sick and wounded men across the Atlantic, and by train across Canada, until her own demobilization in late November 1919, she would have had the chance to ponder the reintegration of returning soldiers (and nurses) into civil society [see Ernest Henry Scammell*]. Gass’s attempt, in 1940, to interest the military in having medical social workers provide follow-up for men rejected by or discharged from the army suggests her ongoing concern for reintegration. In 1946 she would be named to the advisory committee of the newly created Social Services Section of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Her own reintegration into civil society after the First World War involved the study of social service at McGill (1920–21) and employment as a social worker and then as secretary of the Family Welfare Association of Montreal. During this time she joined a club of 16, known as the Hospital Social Workers, begun in 1920.

In 1924 Gass embarked on a 28-year career as the director of the social service department at the Western (as the Western Division of the Montreal General Hospital was known). Two of her colleagues in the Hospital Social Workers club had preceded her as directors; one had been the first such appointee at the Montreal General Hospital in 1912 and the other at the Western in 1914. Gass was thus part of the promotion and development of medical social work as a new profession for women. Together, the women were expanding the early 20th-century movement in the United States of social work in medicine. Where once volunteers had haphazardly met the socio-material needs of hospital patients, these “new women” – many of them, like Gass, with a nursing background – argued for a more professional approach. By 1929 Gass had honed her own work at the Western: “Through study of the patient’s experience, social work should aid in medical diagnosis; through teaching and through changes made in home and work, it should aid in medical treatment; and it should help the administration of the hospital through a special knowledge of neighbourhood characteristics, needs and resources.”

This statement amounts to a job description of the medical social worker as interpreter; underlying it was Gass’s conviction that illness and recuperation were as much social as physical problems and both had to be tackled. In its work the Montreal group collaborated closely with its American counterparts in the American Association of Hospital Social Workers, formed in 1918 (AAHSW was renamed the American Association of Medical Social Workers (AAMSW) in 1934). Indeed, in 1923 the Montreal club, now the Hospital Social Workers’ Association, became the Eastern Canada District (ECD) of the AAHSW. The president of the ECD (Clare Gass in 1930–31 and again in 1946–47) was automatically on the executive of the larger organization. Ideas, documents, reports, and minutes flowed back and forth among members in a common concern for methods, standards, training, and professional development.

What, then, might a day have been like in the life of Clare Gass, medical social worker? A five-minute walk from her central-west apartment brought her to her offices in the basement of the Western. While greeting her small staff (two, occasionally three, other social workers, a secretary, and a visiting housekeeper), she would make a note to grumble once again about the cramped quarters and the bad air. She then made sure that her staff was still closely involved in patient admissions, an innovation of hers in 1924. Continuing with her day, Clare would assign a worker to interview a recently hospitalized woman and thus determine the state of the family; should anything seem amiss, she would send the visiting housekeeper to sort things out. Quick calls followed to two or three social agencies, seeking household goods or convalescent equipment. And while they were on the line, Gass had questions: What were they doing about the handicapped? Or the epileptics? Meanwhile, she dispatched another worker to the outpatients’ clinic – Clare sometimes went along herself – to ensure that doctors’ instructions were understood and followed. Routine tasks she asked of volunteers, glad of their help but careful to supervise them. (She applied the same scrutiny to nursing students doing field placements with her, and found it gratifying to see their growing interest in the social well-being of the patients.) Then she was off to a meeting with hospital administrators; she had to be seen as an equal with the other directors. In the back of her mind, she might outline a committee report for the monthly meeting of the ECD of the AAHSW that evening (she had surely lost count of the committees she had chaired and the executive positions she had held – all save treasurer). Why ever did she offer her flat for that one meeting? Thank goodness for Granty (Mina Margaret Grant, pre-war friend and flatmate): she was bound to prepare some nice refreshments. Maybe there was some information from Boston’s Simmons College in the mail – how Gass had enjoyed her time there in 1930 and 1931! Simmons had an entire department of medical social work. How long was it going to take before McGill offered similar training? She would have to get on to that too.

And so it went for 28 years.

For six months after her retirement in 1952, Gass organized the social service department of the Canadian National Institute for the Blind [see Charles Rea Dickson*]. She then left for home in Nova Scotia. Her retirement and departure from Montreal coincided with the amalgamation of the social service departments of Western and the Montreal General (a consolidation that eliminated Gass’s position) and with the development of plans for a merger of the AAMSW and the American National Association of Social Workers. One of the final acts in 1955 of “headquarters,” as the Montreal group referred to the AAMSW, was to give Gass emeritus membership. With the merger, the ECD had no choice but to disband and hope for some distinct status within the Canadian Association of Social Workers.

Meanwhile Gass, who had begun to lose her sight, had taken her outspoken, no-nonsense personality and her considerable organizing skills and applied them to community work involving history, drama, photography, poetry, and music in her hometown of Shubenacadie. She still spent part of each summer, as she had done while in Montreal, at a cabin on Martinique Beach, east of Dartmouth, and she still welcomed there her relatives and many of her single, professional women colleagues from Montreal. Family members recall “Aunt Clare” and her friends entertaining, organizing, admonishing, and educating her brothers’ many children. She impressed them with her breadth of experience; she insisted on their respect; but she never told them war stories and she never kept another diary. In all those years, both pre- and post-retirement, she returned only once to Europe, taking a commemorative voyage in 1923 aboard the Metagama, the very ship that had taken her to war in 1915. She tucked a sprig of flowers from that trip into a tiny box marked “Forget-me-nots from Vimy Ridge.” By the time they came to light sometime after her death in 1968 at Halifax’s Camp Hill Hospital, they had turned to dust.

Sources and further information on the life of Lelia Clare Gass can be found in The war diary of Clare Gass, 1915–1918, ed. Susan Mann (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2000). The original diary (1915–16) is held by the Osler Library at McGill Univ. Libraries (Montreal) in the Clare Gass fonds (P185, available at archivalcollections.library.mcgill.ca/index.php/clare-gass-fonds). The fonds also includes photographs, scrapbooks, and ephemera. At the time of writing, the two smaller diaries (1917–18) as well as Gass’s sundry memorabilia are in the possession of her relatives in Nova Scotia, who kindly shared them with the author. The assistance provided by the Gass family in the preparation of this biography is gratefully acknowledged by the author. Two major sources for Gass’s post-war career are held by McGill Univ. Libraries: her Annual reports of the Social Service Dept. of the Western Division of the Montreal General Hospital, published in various formats in Welfare work in Montreal (Montreal), 1925–36 (Rare Books and Special Coll.), referred to in Annual report of the Montreal General Hospital, 1937–46, and reproduced in full, 1947–51 (McGill Univ. Arch., RG 96, containers 352–73); and in the records of the American Assoc. of Medical Social Workers, Eastern Can. district, Montreal branch (McGill Univ. Arch., MG 4022). A parallel life in social work is intriguingly presented in Suzanne Morton, Wisdom, justice, and charity: Canadian social welfare through the life of Jane B. Wisdom, 1884–1975 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 2014). King’s-Edgehill School Arch. (Windsor, N.S.), Edgehill School fonds, calendars and prospectus ser., calendar for 1903–4 and 1904–5. Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), RG9-III-B-2, vol.3704, file 30-11-1 (Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada, Director Medical Services, London, General corr., nursing services), Macdonald to Matron MacLatchy at No.3 Canadian General Hospital, 31 July 1917; vol.3736 (Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada, Director Medical Services, London, Nominal rolls, nursing sisters, no.1 to no.4 clearing stations), No.2 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station, 30 Nov. 1917–29 June 1918. McGill Univ. Arch., RG 96 (Montreal General Hospital), School of Nursing, container 417, file 611 (Register of student agreements); container 424, file 685 (Probationers); container 427, file 688 (Register of nurses’ work, 1909–12). N.S. Arch., “Nova Scotia births, marriages, and deaths,” Lelia Clare Gass, 18 March 1887; Claire Gass, 5 Aug. 1968: archives.novascotia.ca/vital-statistics (consulted 4 Oct. 2022). W. D. Craufurd et al., Peeps into Picardy (London, 1914). R. C. Fetherstonhaugh, McGill University at war, 1914–1918, 1939–1945 (Montreal, 1947). No.3 Canadian General Hospital (McGill), 1914–1919, ed. R. C. Fetherstonhaugh (Montreal, 1928). H. A. Pirie, No.3 Canadian General Hospital (McGill) in France, 1915, 1916, 1917: views illustrating life and scenes in the hospital with a short description of its origins, organization and progress (Middlesborough, Eng., 1918). Cynthia Toman, Sister soldiers of the Great War: the nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (Vancouver and Toronto, 2016).

Cite This Article

Susan Mann, “GASS, LELIA CLARE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 19, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gass_lelia_clare_19E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gass_lelia_clare_19E.html |

| Author of Article: | Susan Mann |

| Title of Article: | GASS, LELIA CLARE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 19 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |