Source: Link

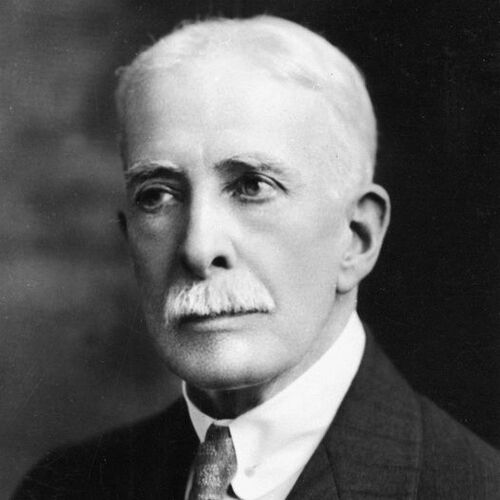

DICKSON, CHARLES REA, physician, electrotherapist, radiologist, and advocate for the blind, b. 16 or 18 Dec. 1858 in Kingston, Upper Canada, son of John Robinson Dickson*, a physician, and Ann (Anne) Benson; d. unmarried 9 July 1938 in Toronto and was buried there in Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

Charles Dickson, co-founder of the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB), earned his first md (1880) in Kingston at Queen’s College. His family was closely connected with the institution: his father was a co-founder of its medical faculty, and his sister Anne was one of that faculty’s first female graduates. In 1881 Charles undertook postgraduate training through the University of the City of New York. It is likely that his later interest in public health was developed during the time he spent at New York’s Bellevue Hospital, a pioneering centre in the field.

After returning to Canada, Dickson set up a practice on Wolfe Island, near Kingston. About 1889 he moved to Toronto, where he developed a special interest in electrotherapy (the application of electrical currents to diseased body parts), a popular forerunner of physical therapy employed by, among others, Dr Jenny Kidd Trout [Gowanlock*]. Dickson was appointed electrotherapist at both the Toronto General Hospital and the Hospital for Sick Children. He acquired an international reputation for his medical work with electricity and would thrice be appointed president of the American Electro-Therapeutic Association. Always of a philanthropic spirit, he treated many patients who could not afford to pay.

The discovery of X-rays by German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen in November 1895 had a profound impact on medical history. Doctors and hospitals worldwide clamoured to acquire X-ray machines, which for the first time gave doctors a means to see inside the bodies of their patients and refine their diagnoses. Toronto General and the Hospital for Sick Children soon purchased such machines, and because of his technological aptitude, Dickson was chosen to oversee their use. Like other pioneering radiologists, Dickson practised both diagnostic and therapeutic radiology, and he published articles on the latter subject.

The new technology would have a fateful impact on Dickson’s health and career. In their headlong rush to use X-rays, doctors failed to appreciate the dangers of radiation, and many practitioners suffered illness or death as a result of their frequent exposure. Dickson was no exception, and he became blind. Some accounts of his life suggest that he lost his sight because of his work with ultraviolet rays (they were used for a form of physical therapy) or a 1908 experiment with X-rays that went wrong, but the most likely cause was his long-term exposure to radiation, which can cause cataracts even at low doses. Dickson’s obituary in the Canadian Medical Association Journal suggests that he was completely blind prior to 1918, and his vision may have already been impaired when he wrote in 1909, “We knew that we were dealing with an agent of great power, but we did not realize that it was capable of exerting any deleterious influence upon tissues exposed to its action … certainly no one thought for an instant of trying to protect himself from any possible injury.”

Dickson’s disability transformed him into a passionate advocate for the blind. His forcefulness in pursuing his goals was a great asset, but his cantankerousness sometimes proved to be a liability. Both qualities can be detected in a 1916 letter Dickson wrote to the Ontario minister of education, Robert Allan Pyne (who was then in England), urging him to appoint a qualified headmaster for the Ontario Institution for the Education and Instruction of the Blind in Brantford:

I implore you not to repeat that fool-trick of the Grits by placing in a position of such importance to those already terribly handicapped, a man whose only qualification is that he is a member of our own party. I am a Conservative from the crown of my head to the sole of my feet and I want my party to commit no such crime for it is nothing short of a crime to the Blind.… You will have a splendid opportunity while in England to … go and see some schools for the blind and take notes. And when you come home be a civilized human being with a conscience, not a party hack!

Dickson deplored the absence of a national organization to coordinate services for the blind, a situation that worsened during the First World War as thousands of soldiers who had lost their sight returned from the Western Front. Writing in 1916 to one of these veterans, Alexander Griswold Viets, Dickson declared: “We want a Canadian National Institute badly and we want it NOW. So we are going to get it – soon. I am not paying any attention to obstacles but am starting with our Eastern Provinces and working Westward Ho!… The Institution will be incorporated whether all come in or not, but we would prefer to have everyone represented. We will have to get over petty jealousies and provincialism and all that tommyrot if we ever expect to arrive anywhere and we are going to arrive.”

The discussions that led to the formation of the Canadian National Institute for the Blind took place around the kitchen table in Dickson’s home at 192 Bloor Street West. As one of the seven original signatories to the CNIB charter in March 1918 and the eldest member of the group, Dickson was a logical choice to become the organization’s first president. His combative personality prevented him from working well with others, however, and he was obliged to resign his position in August. He later served as the first chairman of the CNIB’s Blinded Soldiers Committee and as honorary president of the Sir Arthur Pearson Club of War Blinded Soldiers and Sailors. To help ensure the proper treatment of these veterans, Dickson energetically lobbied the Canadian Army Medical Corps, led by Major-General Gilbert Lafayette Foster, and the Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment, headed by Sir James Alexander Lougheed*. Over the course of two decades, according to scholar Serge Marc Durflinger, Dickson “was to befriend virtually every blinded Canadian soldier.”

Dickson’s other major interest was first aid. He was a friend of American nurse Clarissa Harlowe Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross, and assisted her in developing a national system of first-aid training in the United States. He was a co-founder of the Canadian branch of the Order of St John of Jerusalem (devoted to the prevention and relief of sickness and injury). With Dr George Ansel Sterling Ryerson* he helped establish the Canadian Red Cross Society and the St John Ambulance Association in Ontario.

Despite his international connections, Charles Dickson chose to reside in Canada, preferring, he once remarked, “to live under the British flag.” His achievements were recognized in 1910 by a lifetime membership in the Order of St John of Jerusalem, and in 1937 by a King George VI Coronation Medal. A lifelong bachelor, he died in Toronto on 9 July 1938 of “malignancy of the bladder and prostate,” according to his death record. He had long been in failing health, and he may also have endured financial hardship: his funeral costs were covered by the CNIB. He is quoted as having said, in later years, “I have spent my life doing what people said couldn’t be done.”

Charles Rea Dickson is the author of “Some uses of the X-ray other than diagnostic,” Dominion Medical Monthly (Toronto), 19 (July–December 1902): 72–76; “X-rays and cancer,” Canadian Journal of Medicine and Surgery (Toronto), 26 (July–December 1909): 80–85; and “Radium in the treatment of carcinoma of the cervix uteri,” Univ. of Toronto, Medical Journal, 10 (November 1932–May 1933): 136–40. On 28 Jan. 1905 Dickson read his paper on Niels Ryberg Finsen, who won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, to the Canadian Instit., and it was reproduced first in pamphlet form (Toronto, 1905) and later in the Canadian Instit., Trans. (Toronto), 8 (1910): 99–135, under the title “Niels R. Finsen – his life and work.” A typewritten copy of an unpublished short biography by D. C. Nesbit, titled “Dickson, Charles Rea, m.d., c.m.” (n.p., n.d.), is held by the DCB.

AO, RG 80-8-0-1798, no.004951. CNIB Foundation (Toronto), Arch. LAC, R3647-0-9 (Canadian National Instit. for the Blind fonds). Percy Brown, American martyrs to science through the Roentgen rays (Springfield, Ill., and Baltimore, Md, 1936). J. T. H. Connor, Doing good: the life of Toronto’s General Hospital (Toronto, 2000). J. T. H. Connor and Felicity Pope, “A shocking business: the technology and practice of electrotherapeutics in Canada, 1840s to 1940s,” Material Hist. Rev. (Sydney, N.S.), 49 (spring 1999): 60–70. “Dr. Charles Rea Dickson,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 39 (July–December 1938): 303. S. M. Durflinger, Veterans with a vision: Canada’s war blinded in peace and war (Vancouver and Toronto, 2010). Euclid Herie, Journey to independence: blindness – the Canadian story (Toronto, 2005). A new kind of ray: the radiological sciences in Canada – les sciences radiologiques au Canada, 1895–1995, ed. J. E. Aldrich and B. C. Lentle (Vancouver, 1995). Edward Shorter, A century of radiology in Toronto (Toronto and Dayton, Ohio, 1995).

Cite This Article

Charles Hayter, “DICKSON, CHARLES REA,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dickson_charles_rea_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dickson_charles_rea_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Charles Hayter |

| Title of Article: | DICKSON, CHARLES REA |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |