Source: Link

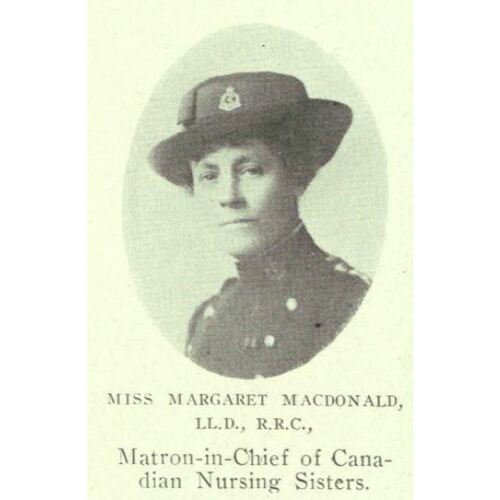

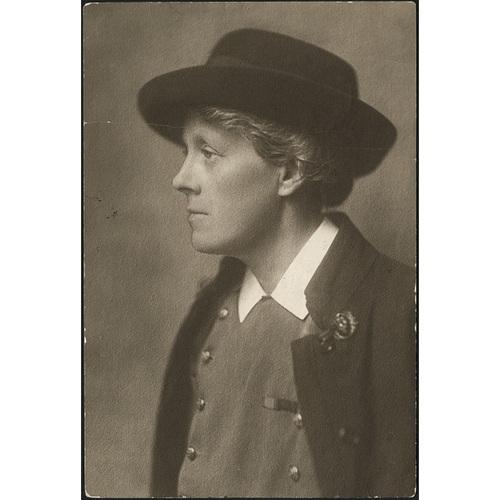

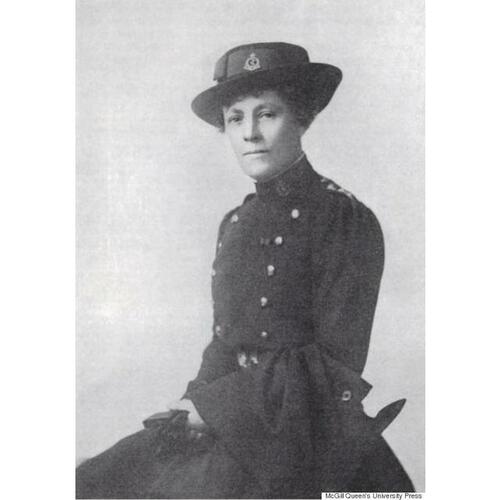

MACDONALD, MARGARET CLOTILDE (Clothilde), nurse and nursing administrator; b. 26 Feb. 1873 in Bailey’s Brook, N.S., daughter of Donald St Daniel (known as D. D.) Macdonald and Mary Elizabeth Chisholm; d. there unmarried 7 Sept. 1948.

From Nova Scotia to New York, South Africa, Panama, London, and the war fields of France and Flanders, Margaret Macdonald’s way in the world was an unusual one. For 30 years she traced an increasingly broad path of professional training and experience, military nursing, and imperial service. The family home she left in 1893 and to which she permanently returned in 1922 is still standing a century later in the rural farming community of Bailey’s Brook, in eastern Pictou County, a testament to the middle-class solidity and prosperity her parents achieved.

Beginnings

Both “Papa” and “Mama” Macdonald were of Scottish Highland Roman Catholic descent. Margaret’s father, whom everyone called D. D., ran a general store that was the community’s link to the outside world, with farm products going out and manufactured goods coming in. Her mother, Mary, brought to the enterprise a fine and prized convent education. All she had had to relinquish on marrying the Liberal D. D. in 1868 was her family’s preference for Conservatives. Together, D. D. and Mary created a spirited, hard-working, hospitable, and fun-loving family, devoted to books and music and political arguments. Nine of the eleven children born over the following two decades survived to adulthood; eight of them, including the six girls, received a classical education.

Margaret, called Maggie, was the third child and third daughter. She took her education the furthest, geographically and professionally. Once she outgrew the local school, she followed her two elder sisters to Stella Maris Convent, a Congregation of Notre Dame boarding school in Pictou, where, in a hierarchical all-female setting, she absorbed an extra dose of discipline along with her studies. In 1890, aged 17, she went to Rockingham (Halifax) for two years of advanced studies in the liberal arts at Mount Saint Vincent Academy, which was run by the Sisters of Charity. Upon graduating in 1892, she received the silver medal for overall academic excellence and took prizes in geography, French, and mythology. Unlike her sisters, who followed the prescribed female path of marriage or the religious life, she chose to become a nurse.

As a “young lady of most excellent character,” as a character reference from Father Andrew McGillivray described her, Margaret was just the kind of student New York City Hospital was looking for. The curriculum of its training school was inspired by Florence Nightingale’s efforts to transform nursing from menial work into a recognized profession for the well-educated, well-disciplined daughters of the rural and small-town middle class. So well did Margaret fit the bill that she was accepted six months shy of the normal admission age of 21.

Nursing experiences

She spent two years at the hospital, learning by doing in a model of nursing education and hospital staffing that would last more than 100 years: students provided multi-ward service to the hospital in return for their training, room and board in a nurses’ home, and a tiny monthly allowance. Maggie loved it. She kept her “Dearest Papa” abreast of all she was learning about contagious diseases, surgery, and post-operative care, and described to him her formal lessons in anatomy, physiology, materia medica, diseases, surgery, obstetrics, and hygiene and sanitation. “You must not think I find it hard,” she reassured him, “for even though the work was twice or three times as hard I wouldn’t leave. It’s just lovely work.” She excelled at it all.

There was no permanent employment for nurses in hospitals at the time, so after graduation in 1895 she took up private-duty nursing in New York City. This work was not steady and required constant searching for positions. Somewhat more secure was district nursing; Macdonald tried her hand at that too, serving as the occasional employee of a private philanthropic agency offering free nursing care to the urban poor. The fact that applications – Macdonald’s among them – poured into the American government with requests to nurse soldiers in the Spanish-American War in 1898 suggests the limitations of the job market and the nurses’ desire to expand their horizons.

Macdonald found her calling in military nursing. She revelled in her first experience, a one-month contract that began on 18 Aug. 1898 and took her to a hastily constructed hospital at Camp Wikoff on Montauk Point, Long Island (New York). The war was over by then, but some of the victorious American soldiers were returning with contagious diseases – yellow fever, dysentery, typhoid – that necessitated their isolation from the civilian population and the provision of skilled nursing care. Macdonald was soon head nurse in a 50-bed ward, prescribing and dispensing medicines on her own authority. She wrote to her mother, “I am having a perfectly delightful experience and would not have missed it for anything.” Indeed, she wanted more of it. She applied for, but did not get, hospital-ship duty. (Some published accounts that she served on the Relief are incorrect.) She later claimed that her youth had disqualified her from going to China as part of an international force to quell the Boxer rebellion. She did, however, succeed in being one of a second group of four nurses sent to South Africa in January 1900. Aboard the Laurentian, they accompanied the second contingent of Canadian soldiers on their way to assist in the United Kingdom’s war against the Boers. (The first contingent, also with four nurses, headed by Cecily Jane Georgina Fane

“Her Ladyship in khaki, fair”

In South Africa for a year-long tour, the Canadian nursing sisters were under British command. Macdonald’s initial posting at Rondebosch, outside Cape Town, was similar to that at Camp Wikoff: she – along with some 25 nurses, British and Canadian – found herself tending an increasing number of sick soldiers in No.3 General Hospital, a hurriedly erected, tented facility. Within three weeks, however, Macdonald and her three colleagues from the Laurentian were the only nurses stationed at Kimberley, 500 miles northeast of Cape Town. The hospital there was also rudimentary and temporary, and most of the soldier-patients were desperately ill with typhoid and dysentery. In late April she was posted to Bloemfontein, where shortages of water, food, and medical supplies, as well as inadequate sanitation, took such diseases to epidemic proportions. Ever healthy herself, Macdonald moved on in July to a much more settled hospital in Pretoria (Tshwane). There she was in charge of 37 patients during the day and 110 when on night duty.

If she found it “impossible to collect one’s thoughts when on active service,” as she wrote to her father in August, she was certainly able to collect her energies for off-duty activities. Excursions to the countryside (by horse, wagon, or carriage), rifle-firing practice, and teas with Canadian or British officers were “very jolly times.” Sharing some of the jolly times was Dr John McCrae*, shipmate from the Laurentian, who caught up with the nurses in Bloemfontein and again in Pretoria. He considered Maggie a “mighty good sort,” addressed her as “Her Ladyship in khaki, fair” in their correspondence, and accepted her gifts and teasing. Macdonald family lore makes a romance of their relationship – it certainly became a lifelong friendship – but her Catholicism and his Presbyterianism would likely have prevented anything serious from developing.

Macdonald returned to South Africa in 1902, when, under the direction of Georgina Pope, she and six other nurses were posted in mid March to a 600-patient, half-tented, half-hutted British hospital in Harrismith. There Macdonald had charge of 36 patients during the day and 250 at night. Once again, more of them were severely ill than wounded. As to when the ongoing guerrilla warfare might be over, she could only guess from the dwindling number of patients in May; peace was proclaimed at month’s end. In July 1902 Macdonald, now enamoured of both military life and travel, was on her way home again. Of the 12 Canadian nurses who served in South Africa, two became the first full-time nurses with the Permanent Army Medical Corps – later the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) – in 1906: Georgina Pope and Margaret Macdonald.

And then to Panama

For two years Macdonald moved back and forth between New York (for work) and Bailey’s Brook (for some good home fun). But she really wanted to go to war again, and so was disappointed that her lack of American citizenship disqualified her from becoming one of the ten American nurses who went to Japan in 1904 to assist in the Russo-Japanese War. Later that year, however, she was offered something just as exciting: a nursing position in Ancón (Panama City), on the Pacific side of the unfinished Panama Canal, which the United States now controlled and intended to complete. Just as in South Africa, her nursing training was giving her access to major international events.

The construction of the canal was an American imperial project run in military style, so Macdonald was right at home. Army surveyors, army engineers, army service corps, and army medical personnel built the canal and kept its huge workforce housed, fed, and moderately healthy. Yellow fever, malaria, tuberculosis, dysentery, and enteritis were, however, a constant presence. Macdonald was familiar with these diseases and also with surgical cases, which were fewer and mostly the result of accidents. Skilled nursing was part of the modernization of the former French hospital at Ancón, as were electricity, screens, new bedding, a modern laundry, and a cold-storage plant. In spite of such up-to-date features, there was still an ongoing battle against “Lizards, Beetles and Bats and a thousand other things [that] parade all through our rooms,” as Macdonald wrote to her sister in October 1904.

Even the social life at Ancón had a military aura. Horseback riding, swimming, camping, and entertainments by senior officers and their wives were all under the careful supervision and organization of the Isthmian Canal Commission, which was anxious that no scandal touch its employees. The fun-loving Macdonald was in great demand by many an admirer – her letters home caused a flurry of romantic curiosity among her sisters – although Margaret had no difficulty in respecting the commission’s expectation that she and the other nurses be well behaved, and she avoided any entanglements. What she was not able to ward off was the malaria that felled her for a week in April 1905 or the grief that assailed her following the death of her father in February 1906. In mid April she took extended leave and went home. She did not return.

Army nursing in Canada

Possibly Macdonald knew of something brewing closer to home. Earlier in 1906 the British had relinquished control of the Halifax garrison, including its 100-bed hospital. As part of a series of reforms, the Canadian military decided to appoint a nursing sister (Georgina Pope) to the hospital. Another appointment soon followed. At age 33, Macdonald finally had a full-time job, in Canada, doing what she liked best: nursing men within a military and medical hierarchy that gave her security, status, and authority. She exercised that authority over patients, male orderlies, and, gradually, civilian nurses, to whom, as future CAMC nursing sister Edith Fanny Hudson noted, she taught the “routine and ethics of Army Nursing” in month-long training sessions for would-be members of the reserve Army Nursing Service. Macdonald was always on the lookout for better ways of doing things: she used the scientific-management phraseology of the day – “efficiency and effectiveness” – to argue, for example, for better working conditions for orderlies.

Her interest in reform took her to England in 1911 on a study tour to observe British plans for organizing and mobilizing military nurses. By then she was the sole nursing sister at the military hospital in Quebec City, where she had been posted in 1909. Her rank of lieutenant qualified her for the study program. Taken aback by a female applicant but probably impressed by the initiative (and cheek) of a junior officer, army officials consented.

In England from June to late December 1911, Macdonald studied the British nursing services. She also renewed contact with people she had encountered in South Africa, including Ethel Hope Becher and Emma Maud McCarthy, now respectively matron-in-chief and matron of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), overseeing some 300 members scattered in British military hospitals at home and abroad. Macdonald noted the obvious contrast of numbers and registered a major difference: Britain’s military nurses, unlike Canada’s, did not have status as officers. Macdonald also observed the contrasts and tensions among the QAIMNS, which was the permanent military nursing service, the Territorial Force Nursing Service, a reserve force, and the Voluntary Aid Detachments, comprising untrained volunteers. She learned, too, of the many reforms that had been made to the army medical service as a result of the South African experience. All these lessons she interspersed with social events: a grandstand seat for the coronation of King George V, sightseeing with a young cousin, and a visit to the Scottish Highlands of her ancestors. She also had enough exposure to suffragette demonstrations in London to confirm her hostility, more likely to the tactics than to the cause.

Once more to war

Full of ideas, Macdonald returned to her nursing duties at the Quebec garrison. She wanted military nursing to be recognized as a specialty, open only to professionally trained nurses. She wanted to increase the number of reserve army nurses by expanding the locations, duration, and content of their training. She wanted to head off the flood of untrained women who would offer to nurse soldiers if war broke out, as it did in August 1914. And when that happened, one of the first orders from army medical headquarters was for Macdonald to report immediately to Ottawa to mobilize Canada’s nursing sisters.

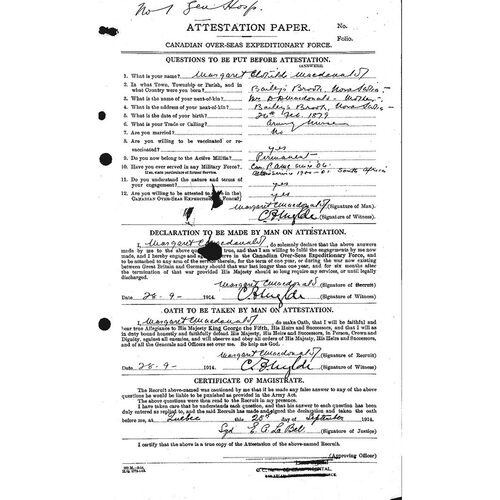

Like the war, her task was presumed to be of short duration. It involved finding, outfitting, and training 100 nurses for two of the five Canadian hospitals heading overseas in October 1914 with the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). There being only five nurses in the CAMC, and only about 50 in the reserves, it was a tall order, made even taller by nearly 1,000 applications pouring into Ottawa. Macdonald weeded out the unqualified, the married, the unhealthy, the ones lacking references, the non-British subjects, and those who were too old. (Conscious no doubt that, at 41, she was over the age limit of 38, she ensured that her formal attestation paper gave her “apparent age” as 35). She interviewed candidates, assessed their character and deportment along with their credentials, selected women from across the country, and worked around the inevitable pressure from influential politicians to take on daughters of prominent friends and constituents. She then outfitted the successful applicants, provided them with formal nursing instructions (largely based on those of the QAIMNS), adjusted army regulations (originally designed for men), and summoned them to Quebec City for initial or refresher courses in military nursing. And then, with an unexpected change of orders, she joined them as matron of No.1 Canadian General Hospital aboard the Franconia, bound for England.

While in London awaiting her deployment, Macdonald registered the enormity of the war effort. Far more was going to be demanded of medical personnel than had been the case during the South African War: there would be more wounded, more hospitals, more doctors, more nurses, and a corresponding increase in administrative and logistical complexity. Macdonald was going to be part of, and indeed broaden, a burgeoning wartime bureaucracy. She had to keep track of her nurses, appoint them to postings, assess their working conditions, move them about, grant them leave, reinforce their numbers, and ensure their safety, security, health, and welfare. She and those she supervised had to do impeccable work and behave irreproachably: at stake was her ambition to see army nurses regarded as professionals. With 100 nurses working across two hospitals, the task could be managed. Foreseeing the likelihood of a large expansion – eventually there would be 2,800 nurses in 33 hospitals – Macdonald soon proposed an extra layer of nursing administration: like Britain, Canada should have a matron-in-chief and she should fill the position. Her army superiors concurred.

Matron-in-chief

In early November 1914, Matron-in-Chief Macdonald relinquished the active nursing of men to assume administrative power over women. With the title went the rank of major, a first for a woman anywhere in the British empire. Her rank meant pay equal to that of other (male) majors in the CEF: $3.00 (and a messing allowance of $1.00) per day, plus $27.33 monthly for lodging, and an additional field allowance when in Europe on inspection tours. Travel and uniform costs were also borne by the army. Her remuneration allowed her to live well in London and to save more than half of each month’s salary.

Macdonald’s title and rank, augmented by the honour of the Royal Red Cross in 1916, gave her a privileged position both in the military and in English high society. In her London office, with a core staff of three, she reported to the director of medical services. Despite the turmoil occasioned by the succession of three different directors – Guy Carleton Jones, Herbert Alexander

For five years Macdonald kept close control of her nurses. To accustom them to the work, she placed them initially in Canadian hospitals in England, more numerous than those in France or Greece. She knew the nurses were always keen to be close to the action, whether in a large general hospital or a smaller stationary one (both well back from the front lines), or, better still, in a casualty clearing station within two to three miles of the fighting. For the latter units Macdonald insisted that only the very best nurses get the coveted six-month posting. Through it all, she kept in mind the nurses’ wishes, their matrons’ needs for reinforcements, and the British authorities’ inclination to poach Canadian nurses for their own hospitals.

She also scrutinized her nurses’ well-being. They were to report to her office whenever they were in London, and she gauged their state of mind and body. Should anything be amiss, she quickly organized leave, medical attention, a stay in a home for respite, or a lighter posting in a convalescent hospital or on a hospital ship transporting wounded soldiers back to Canada. She insisted that in their work they have regular hours off with healthy recreation, including bicycle riding and dancing, the latter much to the chagrin of British nursing authorities, who prohibited such activity. And she made frequent tours to inspect the Canadian hospitals, matrons, and nurses. Nothing escaped her eye. She even took an interest in her nurses’ love lives. But she had no say over death, and had to bear the loss of some 40 of her nurses to illness, to the bombing of two Canadian hospitals in the spring of 1918, and to the torpedoing of the Canadian hospital ship Llandovery Castle on 27 June 1918 [see Rena Maude McLean*].

Post-war life

A full year of post-war mopping up and winding down kept Macdonald in London until November 1919. Unlike her nurses, who were demobilized on their return to Canada, her position was permanent. Or so she thought. Army officials in Canada were more familiar with her domestic counterpart, Edith Catherine Rayside, matron-in-chief of military nurses in Canada since 1917, who was herself demobilized in June 1920. What then to do with Macdonald? Her supervisors in Ottawa asked her to prepare a history of the wartime nursing service. She tried for two years but ran into the embarrassed silence of her nurses. They had loved their work – of which silence was an integral part – and they had survived; so, like most veterans [see Edward Turquand

At age 50, Canada’s first matron-in-chief, with a distinguished military career behind her and feted by women’s organizations across the country, was living at her family home in Bailey’s Brook, learning to take up the more conventional role of a proper middle-class countrywoman. She gave public addresses, kept in contact with her wartime nursing colleagues, made a few more desultory efforts at gathering their recollections, accepted the honorary presidency of the Overseas Nursing Sisters’ Association of Canada, unveiled the plaque to the nursing dead in the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa in 1926, and attended military anniversaries in full regalia. She turned down an offer in 1935 to have her name proposed for an obe, although in 1920 she had accepted an honorary doctorate from St Francis Xavier University and the awarding of the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Committee of the Red Cross. In September 1939, at age 66, she let the military know that she was available for service as Canada went to war again. She was not called upon. She spent the war years at her home in Bailey’s Brook, where she died in 1948, at the age of 75.

Had Margaret Macdonald been a man, she might have had a long and increasingly rewarded career either in medicine or the military (or both). As a woman, only one occupation was then open to her in the modern army, and although she used it to shape a career for herself and to develop the specialty profession of military nursing, it offered scant hope of continuing advancement after the reduction in personnel in peacetime. For a few years she had the heady experience of what she called “sex equality,” and then it was over. Still, she had made the most of the bit part on the world stage that the imperial ventures of Britain and the United States had offered her.

This account draws extensively on the author’s biography, Margaret Macdonald: imperial daughter (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2005), which includes further information and lists the sources used. Readers interested in Canada’s First World War nursing sisters can also consult K. E. Dewar, Called to serve: Georgina Pope, Canadian military nursing heroine (Charlottetown, 2018), Cynthia Toman’s Sister soldiers of the Great War: the nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (Vancouver and Toronto, 2016), and Dianne Dodd’s “Canadian military nurse deaths in the First World War,” Canadian Bull. of Medical Hist., 34 (2017): 327–63.

Cite This Article

Susan Mann, “MACDONALD, MARGARET CLOTILDE (Clothilde),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_margaret_clotilde_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_margaret_clotilde_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Susan Mann |

| Title of Article: | MACDONALD, MARGARET CLOTILDE (Clothilde) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |