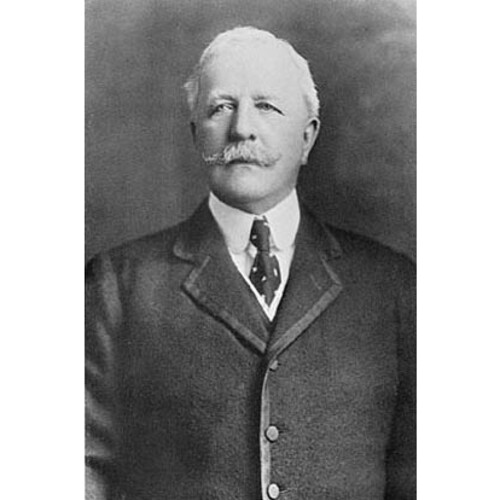

![Description Vincent Meredith Date 1915(1915) Source [1] Author inconnu, publié dans: Illustrated Montreal Old and New, 1915, p.137

Original title: Description Vincent Meredith Date 1915(1915) Source [1] Author inconnu, publié dans: Illustrated Montreal Old and New, 1915, p.137](/bioimages/w600.4087.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MEREDITH, Sir HENRY VINCENT, banker and philanthropist; b. 27 Feb. 1850 in London, Upper Canada, son of John Walsingham Cooke Meredith and Sarah Pegler; m. 14 Nov. 1888 Isobel Brenda Allan (d. 1959) in Montreal; they had no children; d. there 24 Feb. 1929 and was buried in Mount Royal Cemetery.

Vincent Meredith was born into a remarkable family of Anglo-Irish immigrants who had come to the Canadas in 1834. Among his father's brothers were William Collis, who would be appointed a chief justice, and Edmund Allen*, who would serve as a senior federal civil servant. Vincent's father became a court clerk and a successful real estate and insurance agent in London. Into "a home rich in cultural elements" were born eight sons and six daughters. The eldest son, William Ralph, was to become the provincial Tory leader in 1879. Vincent's other brothers would enjoy success in their professions.

After an initial education at home, Vincent briefly attended the London Collegiate Institute. In May 1867 he joined the Hamilton branch of the Bank of Montreal as a clerk at a salary of $200 per year. Banking in mid-19th-century Canada offered young males the opportunity of attaching themselves to the emerging urban professional class. Starting salaries and conditions – long hours and frequent transfers – were poor, but the prospect of long-term security and social status sustained them. The Bank of Montreal was Canada’s oldest and most widely based bank, so Meredith’s clerking career saw him posted to branches in Port Hope, Montreal, London, and Simcoe. In 1871 he graduated to teller in Ottawa at a yearly salary of $500 and in 1875 he was appointed an accountant in London at $1,100.

The bank’s recognition of Meredith’s potential became evident in 1879 when he was brought to the head office in Montreal as assistant inspector. Bank inspectors ensured overall operational integrity; promising employees were appointed inspectors to allow them an intimate knowledge of the bank’s entire system. Meredith was made an assistant manager in Montreal in 1887; in 1889 he became a manager at the head office at $5,000 a year. The appointment to Montreal had put him on the doorstep of national commerce and industry and given him an entrée into Anglo-Montreal society. In 1888 he had married Isobel Brenda, the daughter of Montreal steamship magnate Andrew Allan*. They would have no children, but would quickly establish themselves as linchpins of Montreal philanthropy. Meredith joined the Montreal Garrison Artillery Brigade, in which he would rise to command a battery, and he helped found the Montreal Winter Club. In 1894 the Merediths commissioned Montreal architect Edward Maxwell to build them a Queen-Anne style mansion – Ardvarna – on Pine Avenue.

According to an early-20th-century newspaper, Meredith was “alert, keen and absolutely exacting as to the details of the bank.” The erect, military bearing that he would retain to the end of his life gave him an air of authority. He epitomized the values of Canadian banking: integrity and meticulousness. In 1903 he was appointed manager of Montreal’s main branch and assistant general manager to Edward Seaborne Clouston*. General managers such as Clouston oversaw the bank’s operations and its strategic course. The bank’s presidency had generally been bestowed on a Montreal capitalist; presidents Sir George Alexander Drummond* and Richard Bladworth Angus brought railway and manufacturing connections to their often nominal banking duties. Clouston’s resignation in November 1911 reflected his chagrin at being passed over for the presidency by Angus; it also opened the way for Meredith’s appointment as general manager in December at $30,000.

When Angus retired in 1913, the bank appointed a banker born to be its president – Meredith – at a yearly salary of $40,000. His place as general manager was filled by another seasoned banker, Sir Frederick Williams-Taylor. For the next 14 years the combination of the cautious, retiring Meredith and the urbane, outgoing Williams-Taylor would guide the bank through tumultuous times. Meredith’s presidency soon encountered the commercial slump of 1913 and then it would face the unprecedented challenge of a world war. Depression would follow and not until the end of his presidency in 1927 would Canada’s economy return to any degree of normality. Meredith’s tenure would thus be one of constant adjustment to new circumstances.

The Bank of Montreal grew steadily during Meredith’s presidency. From assets of $244,800,000 in 1913, it more than tripled its base to $831,500,000 in 1927. Dividends increased to a steady 14 per cent by the 1920s. Despite problems in revolutionary Mexico, the bank grew internationally as well. Domestic growth was supplemented by amalgamations it initiated with the Bank of British North America (1918), parts of the Colonial Bank (1920), the Merchants’ Bank of Canada (1921), and the Molsons Bank (1924). Through these years Meredith sat as president of Royal Trust, the bank’s trust company. He was also a director of an array of Montreal-based companies, most notably the Canadian Pacific Railway and Dominion Textile. At the same time he directed his philanthropy to such institutions as McGill University and the Royal Victoria Hospital.

During World War I, Meredith adeptly perpetuated the bank’s role as Ottawa’s banker and fiscal agent abroad. He held the ear of federal finance minister William Thomas White*. In 1914, for instance, Meredith was pivotal in advising White on wartime monetary arrangements; the Finance Act of 1914 suspended the traditional convertibility of dominion and bank notes into gold and for the first time in Canada introduced the creation of government-backed national credit. With the closure of Canada’s capital markets in London, England, the Bank of Montreal facilitated the placing of Canadian war loans in New York and then helped to harness Canadian investors to the national war bond effort. In London, the bank acted as banker to the Canadian military forces in Europe. Closer to home, Meredith spearheaded the bank’s donation of a machine-gun battery, named Borden’s Motor Machine-Gun Battery, to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. At the same time, he encouraged employees to enlist and ordered that the bank continue to pay their salary for the first six months of military duty. When its retail staff became depleted, he issued instructions that women be taken on as “emergency staff.” On 14 Nov. 1916 he was created a baronet for his wartime services to the nation. For her part, Lady Meredith acted as president of the Purple Cross Service for the Care of Wounded and Disabled Horses on the Battlefield.

Peace, Meredith believed, would bring a return to Canada’s traditional formula for national growth: the development of natural resources, protected manufacturing, an open-door immigration policy, and reliance on foreign borrowing offset by export earnings. The post-war period, however, refused to fulfil his predictions. Only in the late 1920s did words such as “satisfactory” re-enter his public assessments of Canada’s performance.

Meredith’s adherence to the economic status quo was echoed in his deeply conservative leadership. In part, his caution was moulded by a realization that as the government’s banker, the Bank of Montreal had the most to lose from changes to the structure of Canadian banking. In 1918 the general manager of the Royal Bank of Canada, Edson Loy Pease, had used his stature as president of the Canadian Bankers’ Association to champion the idea of a central bank capable of governing the creation – the “rediscount” – of national credit. Sensing that Pease’s scheme was a covert attempt to dethrone his bank, Meredith urged White to extend the Finance Act into peacetime; the nation faced too many other post-war challenges to tamper with the way in which national credit was governed, he argued. White heeded this advice, but in the 1920s Canada’s lack of an expansive credit mechanism tarnished the credibility of the banking system, particularly in the populist west. When negative sentiments surfaced in 1923 during the revision of the Bank Act, Meredith attacked “the peculiar tenets which regard banking as the instrument of capital and a public menace.”

Compulsive caution tainted Meredith’s decisions. The amalgamations during his tenure had done little to extend the bank’s reach, merely adding branches where the bank was already well rooted. Other banks used mergers and lending policy more aggressively to expand their share of the market. Consequently, the Royal Bank surpassed the Bank of Montreal in assets in 1925, becoming Canada’s largest bank. Meredith came to regard Pease with contempt and would not even speak to him.

In 1927, immediately after the bank’s annual meeting, the board of directors, possibly concerned over the bank’s slipping fortunes, created the position of chairman of the board and appointed Meredith to it, shifting him out of the president’s office and installing vice-president Charles Blair Gordon* in his place. Meredith continued to chair the board’s executive committee, but in July 1928 he was stricken with cerebral paralysis. He died at home about seven months later. His funeral at Christ Church Cathedral was attended by the city’s commercial and political elite. Tributes represented Sir Henry Vincent Meredith as a hybrid of old Canadian financial conservatism and new professional banking. He left bequests totalling $575,000 to the Royal Victoria Hospital, McGill University, and Bishop’s College (both academic institutions had conferred honorary degrees on him in 1927) and to two special pension funds for bank employees, one in particular for women employees.

Arch., BMO Financial Group (Montreal), Bank circular copybooks, 1914–18; General managers’ scrapbooks, 1920–29; Letter and cable copybooks, 1913–18; Sir H. V. Meredith biog. and corr. files; Sir F. W. Taylor biog. file; Staff ledger, L–Mac. BCM-G, RBMB, St Paul’s Presbyterian Church (Montreal), 14 Nov. 1888. LAC, MG 26, H; I; MG 27, II, D18. Royal Bank of Canada Arch. (Montreal), RBC 2, 43G PeaE (biog. file); 46A, WA1 (F. T. Walker reminiscence file). Bank of Montreal, Annual general meeting, 1913–29. [Archibald Bremner], City of London, Ontario, Canada: the pioneer period and the London of to-day (2nd ed., London, 1900; repr. 1967). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Merrill Denison, Canada’s first bank: a history of the Bank of Montreal (2v., Toronto and Montreal, 1966–67), 2. A. B. Jamieson, Chartered banking in Canada (Toronto, 1953). “The late Sir Vincent Meredith, bart.,” Canadian Bankers’ Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 36 (1928–29): 211–14. Duncan McDowall, Quick to the frontier: Canada’s Royal Bank (Toronto, 1993). Donald MacKay, The Square Mile: merchant princes of Montreal (Vancouver, 1987). [H.] O. Miller, A century of western Ontario: the story of London, “The Free Press,” and western Ontario, 1849–1949 (Toronto, 1949; repr. Westport, Conn., 1972).

Cite This Article

Duncan McDowall, “MEREDITH, Sir HENRY VINCENT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meredith_henry_vincent_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meredith_henry_vincent_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Duncan McDowall |

| Title of Article: | MEREDITH, Sir HENRY VINCENT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |