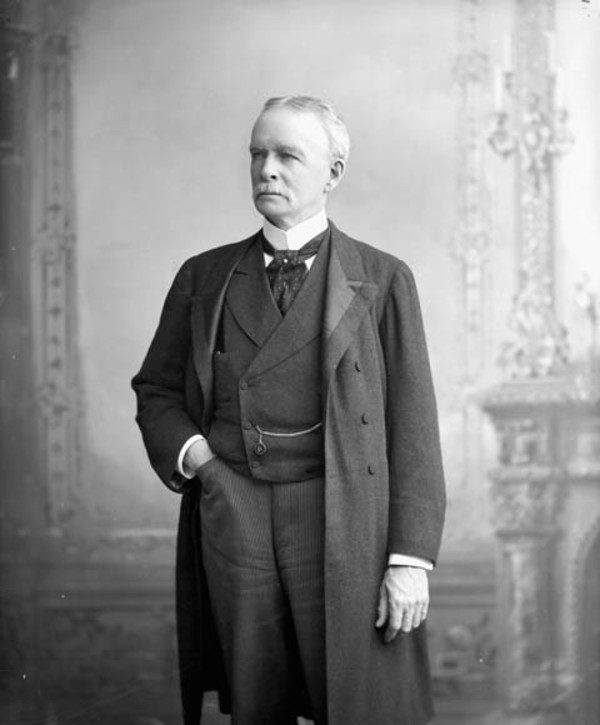

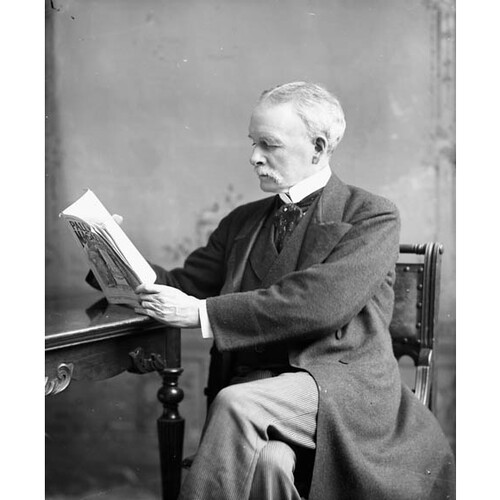

DRUMMOND, Sir GEORGE ALEXANDER, industrialist, financier, and senator; b. 11 Oct. 1829 in Edinburgh, son of George Drummond, a contractor, and Margaret Pringle; m. first 15 Sept. 1857 Helen Redpath, daughter of John Redpath* and Janet McPhee (Macphee), in Montreal, and they had five sons and two daughters; m. there secondly 11 Sept. 1884 Grace Julia Parker*, widow of George Hamilton, and they had two sons; d. there 2 Feb. 1910.

George Alexander Drummond, who came from a well-to-do family, received a good education in his native city. He completed his secondary schooling there and is believed to have studied chemistry at the University of Edinburgh. In 1854 John Redpath, whose second wife was Drummond’s sister Jane, invited him to come to Montreal and manage the technical side of the sugar refinery that he was building near the Lachine Canal.

Until 1876 Drummond’s fortunes were linked with the firm, which became John Redpath and Son in February 1857 when Peter Redpath entered partnership with his father. Drummond’s marriage to Helen Redpath in September helped him rise quickly. In the summer of 1862 John Redpath withdrew from the business and, by a contract registered on 4 July, Drummond and another son, John James, were made partners in John Redpath and Son. This arrangement was ended on 31 Dec. 1867. Peter Redpath and Drummond continued alone until 1 Jan. 1872, when they acquired a new partner, Francis Robert Redpath.

Being a director of a large company, Drummond took a lively interest in politics. He supported the plan for a broad Canadian confederation provided that the viability of the new country would be ensured by a protectionist tariff policy. Thus in 1866 he joined the Tariff Reform and Industrial Association and played an active role in the Liberal-Conservative party. During this period he made lasting friendships with the leading figures in the party and they persuaded him to run in the 1872 federal election in Montreal West against Liberal John Young*, who advocated a free-trade treaty with the United States. He suffered a crushing defeat. Even more serious, two years later the voters put into power Alexander Mackenzie*’s Liberals, who largely favoured free trade.

In Drummond’s eyes this event was a calamity. With the failure of the Liberals to sustain low duties on sugars going into refining, the depression paralysing the Atlantic economy, and the dumping engaged in by foreign industries, the refineries were in serious difficulty. John Redpath and Son shut down early in March 1876, putting 300 men out of work. Encouraged by his friends at the Bank of Montreal, Drummond went abroad to visit his native land and other European countries and to study the new refining processes in Germany. On his return in 1878, Sir John A. Macdonald*’s government, which had been re-elected on a protectionist platform, asked for his advice on implementing the National Policy. The new tariff scale on imports, applied in 1879, contained a specific duty of one cent a pound on refined sugar plus an ad valorem duty that could reach 35 per cent. The Liberals objected that this tariff would make Peter Redpath a millionaire. It was time for restructuring the firm. On 11 June 1879 Drummond had it incorporated as a joint-stock company called the Canada Sugar Refining Company Limited, of which he became president. Peter Redpath retired to England the following year, and on 31 Dec. 1880 John Redpath and Son was dissolved.

During the 1880s Drummond emerged as a recognized spokesman for the Montreal business community. John Redpath, who had been a major shareholder and one of the most influential directors of the Bank of Montreal, had paved the way for him. In 1882 Drummond was named a director of the bank. He had been a member of the Montreal Board of Trade since 1864, when Peter Redpath took over the presidency; he served as its vice-president in 1884 and 1885, and as president from 1886 to 1888. During his presidential term memberships more than tripled.

Drummond was appointed to the Senate by Macdonald in 1888. On the Board of Trade his opinion had been decisive, and he became one of the senators whose views were the most highly valued on commercial, financial, and fiscal matters. Even under Wilfrid Laurier*’s Liberal administration he chaired for a time the Senate’s standing committee on banking and commerce. It was he who persuaded the Canadian government to absorb the debt resulting from the deepening of the channel between Montreal and Quebec, who saw that in 1890 the Bank Act of 1871 was amended so as to make loans more readily available to industrialists, and who in March 1899 led a protest against the city of Montreal’s claim to have a right to impose a tax on fixed capital. The Montreal Manufacturers’ Association was born of this agitation. Although he opposed any form of commercial union with the United States, on 4 Feb. 1889 he did suggest a trade treaty with the West Indies and the Latin American countries.

His presence in the Senate did not prevent Drummond from being active in the Bank of Montreal, as vice-president from 1887 to 1896, de facto president from 1897 to 1904 while Lord Strathcona [Donald A. Smith*] was in London, and official president from 1905 until his death. His appointment to the board of directors was an indication of the growing influence of manufacturers within the institution. This alliance of industry and finance resulted in the establishment over the years of the bank policy of granting longer-term loans and loans against the collateral of warrants, which favoured industrialists. Under Drummond’s guidance the bank undertook a vigorous but prudent expansion. In the period from 1884 to 1910 it opened some 110 branches and increased its employees from 300 to 1,000. It particularly backed the industrial development of Montreal and the ventures of Montreal capitalists in the West Indies and Mexico – in southern Ontario new entrepreneurs had only reinvestment of their profits to count on. It also engaged in banking concentration and in 1892, with the Royal Bank of Canada that had been chartered in 1859, set up the Royal Trust and Fidelity Company, which could carry on operations not yet within the province of the banks, for example, acting as trustees and managing estates. Drummond sat on the boards of and invested personally in companies closely linked with the Bank of Montreal: the Royal Trust Company, the Canadian Pacific Railway, the Mexican Light and Power Company, the Trinidad Electrical Company, the Demerara Electric Company, the Intercolonial Coal Mining Company, the Ogilvie Milling Company, the Canada Jute Company, and the Labrador Company.

Drummond was made a kcmg in 1904 and a commander of the Royal Victorian Order in 1908. He and his wife lived in the style of the upper middle class. In addition to their Montreal residence on Rue Sherbrooke they had a summer home, Gads Hill, at Cacouna, and a magnificent estate, Huntlywood, in what would become Beaconsfield. There they raised pure-bred animals that took numerous prizes in Canada and the United States, and kept a golf course at the disposal of their friends – Drummond was the first president of the Royal Canadian Golf Association in 1895. They were interested in the arts and letters and in activities engaging mind and spirit. Lady Drummond, who was a member of the Women’s Canadian Historical Society, became the first president of the Montreal section of the National Council of Women of Canada, which was headed by Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*]. In the course of their travels and through artists and dealers the couple acquired one of the finest collections of paintings on the continent, including at least five Turners, a Corot, a Velasquez, a Van Dyck, a Rubens, and a Lorrain. Drummond, who had a fine eye for art, was president of the Art Association of Montreal from 1896 to 1899. He and his wife were also deeply engaged in philanthropic works. He had helped found St Margaret’s Home for Incurables in 1894 and had given it the famous house built for Sir William Collis Meredith in 1845 by architect John Wells. He was a member of the Citizens’ League, which sought to improve the quality of life in Montreal, and was also president of the Royal Edward Institute, a dispensary for the prevention of tuberculosis, which was founded in 1909 through the generosity of Jeffrey Hale Burland*. About 1908 Drummond was stricken with heart trouble and retired to Huntlywood. He died on 2 Feb. 1910, one of the last remaining members of the old financial élite that had made Montreal a metropolis.

AC, Montréal, Cour supérieure, déclarations de sociétés, 1, no.1101 (1857); 3, no.4488 (1868); 4, no.5942 (1872); 9, no.752 (1881); 10, no.277 (1882); 13, no.794 (1887); État civil, Anglicans, Church of St John the Evangelist (Montreal), 4 Feb. 1910. ANQ-M, CE1-70, 11 sept. 1884; CE1-126, 3 sept. 1827, 15 sept. 1857. Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 5: 393. Gazette (Montreal), 2 March 1876, 3 Feb. 1910. Globe, 3 Feb. 1910. Monetary Times, 10 Sept. 1897; 31 March 1899; 20 April 1900; 22 March, 5 July 1901; 5 Feb. 1910. Montreal Daily Star, 3 Feb. 1910. Atherton, Montreal, vol.3. The book of Montreal, a souvenir of Canada’s commercial metropolis, ed. E. J. Chambers (Montreal, 1903). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1878; Senate, Debates, 1879, 1889–90, 1895, 1897, 1903. The Canadian parliament: biographical sketches and photo-engravures of the senators and members of the House of Commons of Canada (Montreal, 1906). The centenary of the Bank of Montreal, 1817–1917 (Montreal, 1917). E. A. Collard, The Montreal Board of Trade, 1822–1972: a story ([Montreal], 1972). CPG, 1908. Merrill Denison, Canada’s first bank; a history of’ the Bank of Montreal (2v., Toronto and Montreal, 1966–67), 2. Directory, Montreal, 1881–1902. DNB. Les femmes du Canada: leur vie et leurs oeuvres (s.l., 1900). P.-A. Linteau, Maisonneuve ou comment des promoteurs fabriquent une vine, 1833–1918 (Montréal, 1981). Naylor, Hist. of Canadian business. Guy Pinard, Montréal: son histoire, son architecture (4v. parus, Montréal, 1986– ). Qué., Statuts, 1892, c.79. Redpath centennial, one hundred years of progress, 1854–1954 (Montreal, 1954). Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vol.7. The storied province of Quebec; past and present, ed. William Wood et al. (5v., Toronto, 1931–32), 4. Robert Sweeny, A guide to the history and records of selected Montreal businesses before 1947 (Montreal, [1978]). Terrill, Chronology of Montreal. Beckles Willson, The life of Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, g.c.m.g., g.c.v.o. (2v., Boston and New York, 1915), 2.

Cite This Article

Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin, “DRUMMOND, Sir GEORGE ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drummond_george_alexander_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drummond_george_alexander_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | DRUMMOND, Sir GEORGE ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |