Source: Link

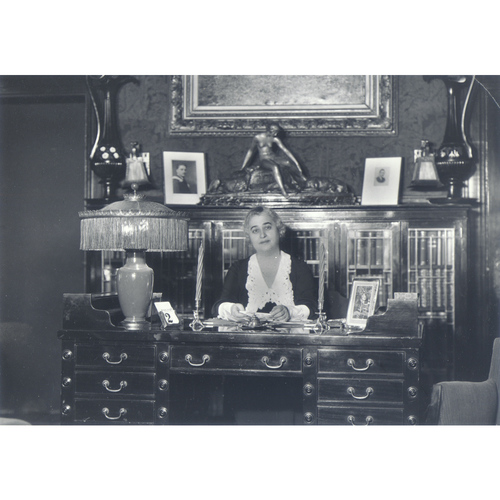

BILSKY, LILLIAN (Freiman), social organizer and administrator, philanthropist, and Zionist leader; b. 6 June 1885 in Mattawa, Ont., one of the 12 children of Moses Bilsky* and Pauline Reich; m. 18 Aug. 1903 Archibald Jacob Freiman* in Ottawa, and they had a son and three daughters, one of whom was adopted; d. 2 Nov. 1940 in Montreal and was buried in Ottawa’s United Jewish Community Cemetery (Jewish Memorial Gardens).

Lillian Bilsky’s father was the first Jew to take up residence in Ottawa, in 1856 or 1857, though he did not settle permanently there until the early 1890s. The city’s Jewish population numbered only a handful in the late 19th century, but, by the time of Moses Bilsky’s death in 1923, it had grown to around 3,000. The Bilskys were fixtures of this community. Moses, who first peddled watches and later operated a successful jewellery business, played a key role in forming the first Jewish congregation, Adath Jeshurun (commonly called the King Edward Avenue Synagogue or shul), in 1892, and he and his wife, Pauline, turned their home into a place where the less fortunate could come for help.

In this atmosphere young Lillian developed a keen social conscience, especially in regard to impoverished Jewish immigrants. As a teenager, she was an important member of the Ottawa Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Society, established by Bertha Lehman* in 1898, and was active in the city’s Children’s Aid Society, where she began working with troubled youth. Her organizational skills were further developed after the outbreak of World War I. Although then a busy mother of three young children, she raised funds for displaced Russian and Polish Jews by arranging concerts and other entertainments. In August 1915 the federal minister of labour, Thomas Wilson Crothers, told Lillian that her fund-raising appeals “should … receive a generous response. You are doing much to mitigate the suffering of the allies from this cruel war.”

Lillian also took a strong interest in the cause of soldiers and veterans, many of whom gathered at her home. She helped to organize recreational outings for veterans, and on one occasion she intervened with the minister of justice, Charles Joseph Doherty, to block the return to Germany of three enemy deserters. An active member of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Comforts Committee, as well as the Ottawa Hebrew Ladies Sewing Circle, she responded without hesitation when the Red Cross appealed for hospital gowns for recuperating veterans. With the assistance of her husband, Archie Freiman, owner of an extremely successful Ottawa department store, Lillian installed sewing machines in her home where Jewish women met weekly to supply the clothing required; the results were so satisfactory that the gowns’ pattern was copied by the American Red Cross. In 1918 the Red Cross sewing group became the Disraeli Chapter of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, which, with Lillian as its regent and with the slogan “No empty Christmas stockings,” sent gifts to the children of 9,000 soldiers.

The previous year, Lillian had helped in the creation of the Great War Veterans’ Association of Canada, precursor of the Canadian Legion. The Disraeli Chapter of the IODE operated a recreation room in the association’s clubhouse. After the war, Lillian directed the poppy campaign (the first was in 1921), a role she would fill until her death. In appreciation of her efforts, on 24 Nov. 1933 the Canadian Legion made her a life member, the only person until that time to hold such an honour. As another tribute, in 1936 the Legion awarded her 1 of the 100 medals struck to commemorate the erection of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France. Lillian’s portrait long hung in the Canadian Legion’s Ottawa office.

A further measure of Freiman’s stature is the part she played in the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918. At the request of Ottawa’s mayor, Harold Fisher, Freiman directed an emergency campaign to help the sick and control the spread of the contagion. For five weeks, working alongside the city’s medical officer, Dr Robert Law, she led a group of 1,500 volunteers who provided food, clothing, and medical care while operating three temporary hospitals. By the time the epidemic had subsided, Freiman had become a beloved and much-admired figure in Ottawa, among residents and government officials alike.

Freiman also dedicated herself to assisting Jews both in Europe and in Canada. In 1920 she met with Frederick Charles Blair*, an unsympathetic official with the federal Department of Immigration and Colonization, to request the admission of 1,000 Jewish Ukrainian orphans into the country. At the time, none of the approximately 137,000 Jewish orphans in Europe, left destitute by war and pogroms, had been allowed to enter either Canada or the United States. In deference to Freiman, Canadian immigration officials authorized the entry of 200 healthy Jewish orphans. Freiman, as president of the Jewish War Orphans Committee of Canada, then launched a national campaign seeking funds and adoptive families. After raising $100,000, she sailed to Antwerp in 1921 to oversee the project. An initial party of 108 children, examined in the Ukraine by Dr Joseph Leavitt, himself a veteran, with the assistance of Montreal bookstore owner Harry Hershman and Hamilton, Ont., alderman William Farrar, arrived soon thereafter and were taken in by Canadian families; one, an 11-year-old girl, was adopted by the Freimans, and Lillian’s parents welcomed another. A second, smaller party of children arrived two weeks later. In recognition of her efforts in this regard, Lillian was elected in 1925 to the honorary committee of the Save the Children Fund.

In 1921 Lillian made it plain that adult Jewish immigrants were just as dear to her heart. With immigration restrictions placing more than 500 newly arrived Jewish refugees in danger of forced return to the Ukraine, Lillian met these distraught Jews at Halifax to offer consolation and hope. One of them, future Montreal-based historian David Rome, later recalled that Lillian encouraged the group “not to cry.” Meanwhile, she pressed the Department of Immigration and Colonization to examine each case on its merits. With her usual persistence, she ultimately succeeded in persuading the department to allow many of these refugees to stay in the country. Her efforts in this area mirrored those of another prominent Canadian Jew, Lyon Cohen.

Over the course of her life, Freiman was involved in a wide range of institutions, regardless of their religious or ethnic affiliation. She was president of the Hebrew Benevolent Society, the Jewish Women’s League of Ottawa, the women’s auxiliary of the Perley Home for Incurables, and the city’s Girl Guides; and vice-president of the Ottawa branches of the Canadian National Institute for the Blind and of the Local Council of Women. She sat on the executives of the Canadian Women’s Club and the League of Nations Society in Canada [see Newton Wesley Rowell*], and was active in the women’s auxiliary of the Independent Order of B’nai B’rith. She also worked to find jobs for the unemployed, lobbied for a day nursery for the children of working women, and, alongside Mother Superior Marie-Thomas d’Aquin, assisted unmarried pregnant women through the Sisters of the Joan of Arc Institute of Ottawa.

Of all her causes, however, none occupied more of her time – and engaged her more deeply – than Palestine. Both Lillian and her husband were committed members of the Zionist movement, which arose in the late 19th century and achieved its first great success when the Balfour Declaration of 2 Nov. 1917 committed the British government to the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Archie, known as “the father of Canadian Zionism,” was elected president of the Federation of Zionist Societies of Canada (later renamed the Zionist Organization of Canada) in 1919, succeeding Clarence Isaac de Sola*, a post he would hold until his death in 1944. Lillian, who inherited her passionate Zionism from her parents, represented the Ottawa branch of the Daughters of Zion at the third convention of the Federation of Zionist Societies of Canada in Montreal in 1903; she was elected president of the Herzl Ladies’ Society in 1910; and she led the Helping Hand Fund for Destitute Jewry in Palestine, organized by Hadassah, an American Jewish women’s benevolent organization, in 1918.

Just after World War I Lillian gave eloquent expression to her passion for the cause of Palestine, “that beautiful far-off land that is to be ours,” when, in an account of the Hadassah convention in Chicago in 1919, she wrote that “the time had come for the women of Israel to unite and prepare for the noble tasks that lie ahead of them. We must concentrate on the work of rehabilitation and reconstruction of our own long-hoped-for-Land, so that from our efforts there shall blossom forth a new nation ready to teach the world a new-old idealism and a long-forgotten spirit of democracy that had its birth on Mount Sinai.” In 1919 she took the helm of the newly formed Hadassah Organization of Canada, which had taken shape through the Helping Hand Fund campaign and which, at Lillian’s suggestion, subsequently affiliated with Great Britain’s Women’s International Zionist Organization, rather than with the American Hadassah, to form Hadassah-WIZO. As its president, informally from 1919 and formally from 1921, she toured Canada several times endeavouring to create a national Hadassah-WIZO organization while also raising substantial amounts of money for the cause. Largely as a result of her efforts, there were no fewer than 111 Hadassah-WIZO chapters in Canada in 1927, and by 1940 that number had grown to 203, with a total membership of more than 7,000. In 1928, with financial assistance from Hadassah-WIZO and Archie Freiman, the national council of the Zionist Organization of Canada purchased a large tract of land in the Emek Hefer region of Palestine and designated it for future colonization by homeless European Jews. Fund-raising for this project continued until 1937. Lillian also found money for the creation of the Girls’ Domestic and Agricultural Science School in Nahalal (Israel) and, at her urging, Hadassah-WIZO assumed financial responsibility for this facility. With the help of the Canadian organization, the school acquired a new wing and later a hospital was built, the latter named for Lillian.

In 1927 Lillian and Archie, with their daughter Dorothy, visited Palestine, and on their return journey they were honoured at Zionist banquets in Paris and London. Over the years Lillian attended gatherings of various international Zionist organizations, including WIZO (as a member of its executive), the Jewish National Fund, and the World Zionist Congress. In 1929 she was the Canadian chair of the Palestine Emergency Fund, created in response to Arab attacks on Palestine Jews, and in 1934 she was appointed dominion chairperson of the United Palestine Appeal. The following year, she declared that “Zionism for us must be not only a political movement … it should be our philosophy of life,” and, with persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany mounting, she increasingly regarded the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine as a matter of life and death. Yet she was not blind to the interests of Palestine Arabs. In 1938 she supported a proposed partition of Palestine into a Jewish state, a Palestinian Arab state, and a mandated territory, declaring in her last Hadassah address: “I voice a prayer for world peace. In the midst of a world beset with strife and misunderstanding and mistrust, let us, as Jews, stand united in our work. May our efforts serve as a beacon for peace, mutual tolerance and understanding among people. God grant us the power to point the way.”

By this time Lillian and Archie had become friends of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King*, whose home at Kingsmere was near the Freimans’ country retreat. King’s views of Jews were conflicted, but, nevertheless, he was supportive of the Freimans’ work. At a Zionist convention held in Ottawa in 1922, King commended Lillian and Archie’s efforts on behalf of this cause, with which, he said, “he felt deeply in sympathy.” Three years later King criticized the Freimans for encouraging Ottawa and Winnipeg Jews to support Arthur Meighen* and his Conservative Party in the federal election. Soon, however, his feelings towards the couple had warmed again, a change of heart no doubt made easier by the fact that the Freimans’ politics evidently shifted in the late 1920s. In 1927 King, in the privacy of his diary, expressed his belief that Lillian and Archie would “come back in line” with the Liberal cause for they were both “liberal at heart.” Subsequently, in the federal election of 1930 that resulted in King’s defeat at the hands of the Conservatives under Richard Bedford Bennett*, the Freimans seem to have supported the Liberal cause, and by 1933 King was referring to them as “solid friends.” In August 1936 King had tea with the Freimans, whom he described as being “greatly distressed” over Nazi persecution of Jews and the inevitability of another world war. He wrote in his diary: “It made me sad to see those good people … being paralyzed with fear.” Sympathetic to the political ambitions of Archie Freiman – who, according to King, wanted a seat in the Senate – the prime minister also was interested in naming Lillian to a government board, feeling that “we should get & keep the good will of the Freiman’s, they are outstanding members of their community.”

In the early 1930s Lillian’s health deteriorated sharply, so much so that she felt compelled to tender her resignation as Hadassah-WIZO president. The resignation was rejected, but the organization did relieve her of the responsibility for daily operations. In 1934 King George V conferred an obe on her for service “on behalf of ex-servicemen as well as his Jewish subjects throughout Canada.” She was the first Canadian Jew to be so honoured. The next year she was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal.

Also in 1935 Lillian had an operation which, in the words of King, revealed a “bad condition,” but her work on behalf of others continued. Her son, Lawrence, remembered that, even during her bouts of illness, “the telephone rang constantly.” In early 1940, from her sickbed, she headed the Youth Aliyah Appeal, raising $18,000 to rescue Jewish children in Europe and resettle them in Palestine. She died on 2 November, known to Jews as Balfour Day after the famous declaration, in the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal.

Lillian Freiman’s body lay at rest first in Montreal and then at her Ottawa home. Government departments allowed Jewish employees to take time off from work to attend the funeral, held at the King Edward Avenue Synagogue. All stores operated by Jews closed. A solemn procession of mourners made its way from the Freimans’ home to the synagogue, where those in attendance for the service included Prime Minister King, Ottawa mayor John Edward Stanley Lewis, Rabbi Maurice L. Perlsweig, representing the World Jewish Congress, and Samuel Bronfman*, president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, whose brother Allan* had married Lillian’s sister Lucy. Perlsweig expressed the feelings of many when he declared that “the news of her passing will come as a personal grief to the multitudes of Zionist workers throughout the world whose affection and confidence she had won by her dedicated and selfless devotion.” Unprecedented in the tradition of Hebrew burial service, a wreath of poppies covered the lower half of the casket.

After attending the funeral, King wrote a diary entry describing Lillian as the “Queen” of Canadian Jewry. The public tributes were just as glowing, and numerous. At a memorial service in Tel Aviv (Tel Aviv–Yafo), Golda Meir, a future prime minister of Israel, described Freiman as a “symbol of what a proud Jewish woman should be.” In Canada, the author Abraham Moses Klein* wrote: “It is difficult to put into language the feeling of great loss which encompasses Canadian Jewry, from one end of the Dominion to the other, at the news of the passing of the late Mrs. A. J. Freiman. Her career, indeed, had become part of the pattern of Jewish life in Canada; there was no ideology or undertaking for the public weal in which she did not manifest a keen interest, and participate, with beneficent activity; and there was no activity which she did not adorn.… A good and noble woman has passed away. All Jewry mourns her and will forever cherish her memory.” Communities in Israel were named for both Lillian and Archie in recognition of their contributions to the Zionist cause.

AO, RG 80-5-0-310, no.5712. LAC, R233-37-6, Ont., dist. Ottawa (100), subdist. St George Ward (E): 22. Ottawa Jewish Arch., Archibald and Lillian Freiman family fonds. I. [M.] Abella, A coat of many colours: two centuries of Jewish life in Canada (Toronto, 1990). I. [M.] Abella and Harold Troper, None is too many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933–1948 (Toronto, 1983). Michael Brown, “Lillian Freiman,” in Jewish Women’s Arch., Jewish women: a comprehensive historical encyclopedia: jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/freiman-lillian (consulted 12 Dec. 2015). Bernard Figler, Lillian and Archie Freiman: biographies (Montreal, 1961). Merna Forster, 100 more Canadian heroines: famous and forgotten faces (Toronto, 2011). Lawrence Freiman, Don’t fall off the rocking horse: an autobiography (Toronto, 1978). The Jew in Canada: a complete record of Canadian Jewry from the days of the French régime to the present time, ed. A. D. Hart (Toronto and Montreal, 1926). Ontario Geneal. Soc., Ottawa branch, The United Jewish Community Cemetery, concession IV, lot 7, Gloucester Township, Carleton County, Bank Street, Highway 31, Ottawa, Ontario (Ottawa, 1997), sect.1: 1–2. S. E. Rosenberg, The Jewish community in Canada (2v., Toronto and Montreal, 1970–71). J. H. Taylor, Ottawa: an illustrated history (Toronto, 1986). G. [J. J.] Tulchinsky, Canada’s Jews: a people’s journey (Toronto, 2008); Taking root: the origins of the Canadian Jewish community (Toronto, 1992). Who’s who in American Jewry, ed. [Julius Schwartz and S. A. Kaye] (3v., New York, 1927–38), 3 (1938–1939, ed. John Simons).

Cite This Article

Shirley Berman, “BILSKY, LILLIAN (Freiman),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bilsky_lillian_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bilsky_lillian_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Shirley Berman |

| Title of Article: | BILSKY, LILLIAN (Freiman) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2017 |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |