RODIER, JOSEPH-ALPHONSE, typographer, trade-union leader, and labour columnist; b. 22 March 1852 in Troy, N.Y., son of Benjamin Rodier; m. 8 April 1872 Catherine David in Montreal, and they had five children; d. there 19 April 1910 and was buried 22 April in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Joseph-Alphonse Rodier was a dominant figure in the Quebec trade-union movement at the beginning of the 20th century. A typographer, he played a prominent role in the leadership of the Knights of Labor, an American organization that advocated sweeping social reform, and he later ardently supported international trade-unionism. Convinced that it was important for unions to go beyond economic action, he was instrumental in establishing the Labour Party in Montreal in 1899. His daily columns in La Presse from 1898 to 1903 and subsequently in La Patrie gave him great influence in union circles.

The son of Benjamin Rodier, who had fled to the United States after the rebellions of 1837–38, Joseph-Alphonse learned his trade at Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe and then went to work at the Montreal newspaper La Minerve as head of shipping. His formal schooling was limited, but he developed a taste for reading and acquired a thorough knowledge of labour issues. In 1870, while still young, he became one of the charter-members of the Union Typographique Jacques-Cartier in Montreal, which was affiliated with the International Typographical Union. President of his union from 1891 to 1893, he later became its organizer for the province of Quebec.

In 1886 Rodier’s union sent him as a delegate to the founding of the Central Trades and Labor Council of Montreal, the first organization established to represent unionized workers in their dealings with municipal government. His interest in politics evidently emerged during this period, since he subsequently became a regular delegate to the council. It was an era of harmony between the international unions and the order of the Knights of Labor, and in 1892 Rodier was elected master workman (president) of District Assembly 19 of the Knights of Labor in Montreal; he was also a delegate to the convention of the order in New Orleans in 1894. A few years later, however, he became a fierce opponent and proposed that the order’s assemblies be barred from the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada on the grounds that they “represent nothing and no one.” He served on the committee appointed to revise the TLC’s constitution in 1902, a process that led to the expulsion of the Knights of Labor assemblies and placed the TLC under the sole control of the international unions.

During the same period, goaded especially by his disappointment with the Liberals’ failure to carry out promised reforms, Rodier advocated the formation of a labour party. He believed that to obtain justice, workers had to elect to parliament people of their own who would push for legislation in their interest. In March 1899 he was chosen organizer of the Labour Party of Montreal, which ran its first candidate in the November 1900 federal election. Four years later he campaigned for others and became chair of the party’s executive committee. One of his candidates, Alphonse Verville*, was finally successful in a by-election in Maisonneuve riding on 23 Feb. 1906. The party platform, based on that of the British Labour Party and the political demands of Canadian trade unions, included policies that seemed radical at the time: health insurance, old-age pensions, nationalization of utilities, a graduated income tax, universal suffrage, and establishment of a department of public instruction. Rodier advocated all these pleasures in his columns for La Presse and later for La Patrie.

At the time when Rodier was hired as a columnist in 1898, La Presse described itself as a people’s newspaper with no political ties. Rodier was a personal friend of the owner, Trefflé Berthiaume*, and gave free rein to his own opinions in his daily column. In December 1903 he left La Presse for La Patrie, having been fired by Olivar Asselin*, the recently appointed news editor at La Presse, who did not appreciate Rodier’s grammatical mistakes or style. Both Asselin and Rodier were temperamentally unsuited to accommodation.

Rodier was accused of being a radical and a socialist in his time, but his well-thought-out ideas belong to what would now be called the social democratic stream. Although he denounced trusts and monopolies, he did not call for the overthrow of the capitalist system. He recognized that capital and labour had opposite interests, but he still considered it possible for workers to get along with employers. Rodier believed that to counterbalance the power of the employers, employees must join together in unions – even American ones, if they made the workers more powerful. They should also use their votes to influence the government, which he accused of being dominated by businessmen and professionals. In his view, governments that were more sensitive to the popular will would limit the power of trusts, nationalize utility companies, eliminate the “militarist scourge,” institute universal suffrage (including women’s suffrage), allow judges to be elected by the people, and abolish the Senate and the Legislative Council. To have such new policies adopted, workers had only to elect working-class representatives from a party that promoted their interests.

Joseph-Alphonse Rodier became a figure of considerable stature in Montreal. Mgr Paul Bruchési*, the city’s archbishop, visited his bedside shortly before he died, and more than 2,000 workers accompanied his remains in the funeral procession to the cemetery. In homage to Rodier’s commitment to the labour cause, his friends took up a collection for a monument in his memory. A large cross unveiled in 1916 at Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery, it bore the legend, “the grateful labour unions.”

AC, Montréal, État civil, Catholiques, Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges (Montréal), 22 avril 1910. ANQ-M, CE1-51, 8 avril 1872. Rodolphe Girard, “J.-A. Rodier, homme très sincère, fut un véritable chef ouvrier,” Le Petit Journal (Montréal), 28 août 1949, suppl.: 15. La Patrie, 19 avril 1910. La Presse, 19 avril 1910: 1–2, 10. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Jacques Rouillard, “L’action politique ouvrière, 1899–1915,” Idéologies au Canada français, 1900–1929, sous la direction de Fernand Dumont et al. (Québec, 1974): 267–312. André Vidricaire, “La philosophie devant le syndicalisme: un typographe et un philosophe ou le conflit de deux discours en 1900,” Objets pour la philosophie . . . , sous la direction de Marc Chabot et André Vidricaire (2v., Québec, 1983), 1: 227–89.

Cite This Article

Jacques Rouillard, “RODIER, JOSEPH-ALPHONSE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rodier_joseph_alphonse_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rodier_joseph_alphonse_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacques Rouillard |

| Title of Article: | RODIER, JOSEPH-ALPHONSE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |

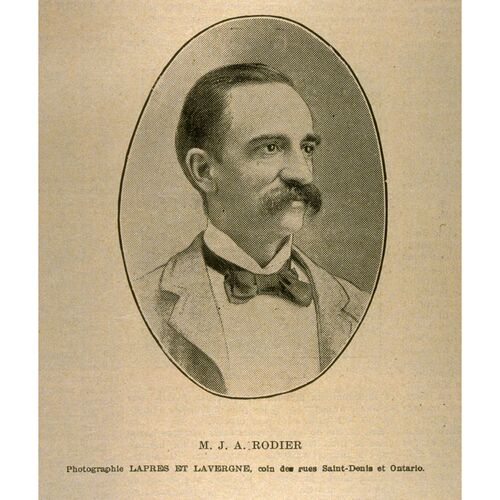

![M. J.A. Rodier [image fixe] / A.J. Rice, Laprés & Lavergne Original title: M. J.A. Rodier [image fixe] / A.J. Rice, Laprés & Lavergne](/bioimages/w600.6368.jpg)