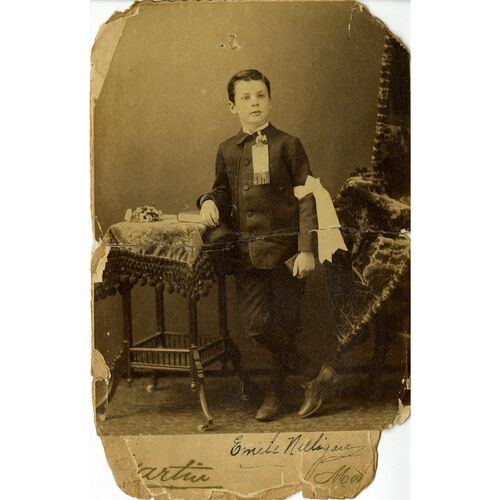

NELLIGAN, ÉMILE (he also signed Émil Nelligan, Émil Nellighan, and Émil Nélighan, and used the pseudonym Émile Kovar), poet; b. 24 Dec. 1879 in Montreal, son of David Nelligan, an assistant postal inspector, and Émilie-Amanda Hudon; d. unmarried 18 Nov. 1941 in Montreal and was buried there three days later in the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Family, youth, and education

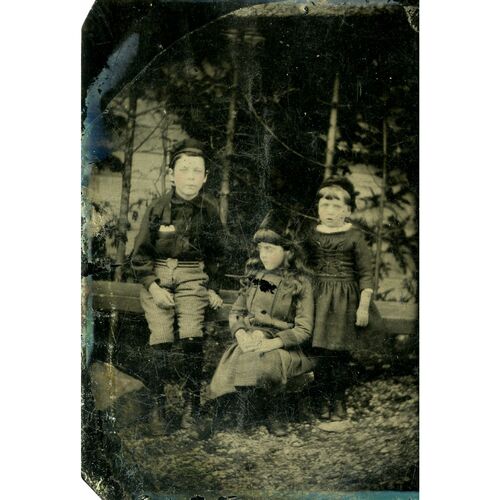

Born to a father of Irish extraction and a French Canadian mother, Émile Nelligan grew up in an environment that was Roman Catholic and bilingual. He lived with his parents in the home of his paternal grandfather, Patrick Nelligan, at 602 Rue Lagauchetière (De La Gauchetière Ouest), Montreal. In the spring of 1883, the young family, which now included another child (Éva, born on 29 Oct. 1881), moved into an apartment at 195 Rue de Bleury (De Bleury), where Gertrude-Freda was born on 22 August. From 1885 to 1893 Émile attended several elementary schools. In September 1885 he was enrolled at the Académie Saint-Antoine, run by the Brothers of the Christian Schools, and starting the following August, he continued his education at the École Olier. Numerous absences, the reasons for which are unknown, affected his marks, and he had to repeat his third year in 1889–90. In 1886 the family had moved into an apartment near Square Saint-Louis at 112 Avenue Laval; in the spring of 1892, they would settle farther northwest, at number 260 on the same street, near the Rue Napoléon. Until the end of his life, Nelligan would give this as his address, and it was where he would compose most of his poems. From September 1890 to June 1893, he attended the Collège du Mont-Saint-Louis, also run by the Brothers of the Christian Schools, where he apparently regained his taste for study, perhaps because the institution’s clergy encouraged artistic expression in their pupils. On 27 Dec. 1892 he gave his first public recitation there.

In September 1893 Nelligan embarked on secondary school studies as a day pupil at the Sulpicians’ Petit Séminaire de Montréal, where he was subjected to the rigorous discipline imposed on seminarians destined for the priesthood. Poor academic results forced him to retake his Latin courses twice. In 1895 he was advised to change schools. In March 1896, following an eight-month interruption, Nelligan entered the Jesuit-run Collège Sainte-Marie as a day pupil in the second year (Syntax). In September he had to repeat the class. Father Théophile Hudon, his mother Émilie-Amanda’s second cousin, taught literature there and was tasked with guiding the young man in his studies. Nelligan attended the college for two semesters, until February 1897. Now aged 17, he was already two years behind his classmates, and despite his parents’ opposition, he decided to abandon his schooling. He could not envision any profession but that of poet.

First poems

The year 1896 marked Nelligan’s official debut in the world of poetry. On April 4 and 16 he participated in artistic and literary soirées organized in aid of the work of the Blessed Sacrament Fathers, during which he publicly recited a few poems composed by others. It was not until the last days of spring that Nelligan’s own poems were published. Between 6 June and 19 September, nine of them, signed with the pseudonym Émile Kovar, appeared in the Montreal weekly Le Samedi.

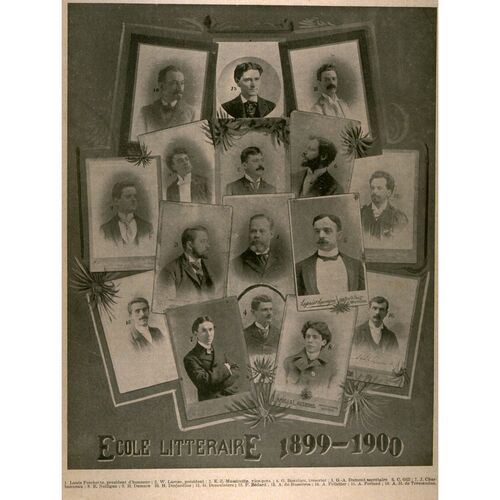

Early in the following year, Nelligan sought entry to the École Littéraire de Montréal [see Gonzalve Desaulniers*; Georges-Alma Dumont*]. The group then had some 20 members who had been meeting weekly since November 1895. Nelligan was admitted to their company on 10 Feb. 1897, presenting two new pieces, “Berceuse” and “Le voyageur”; 15 days later he attended a meeting at which he met Joseph-Marie Melançon* (known as Lucien Rainier), Arthur de Bussières, and Charles Gill*, who were already involved in the École’s activities. However, aside from his being present at three more meetings and reading his poem “Les tristesses” at the one on 4 Feb. 1898, nothing is known about his contribution to the literary group’s undertakings between that date and the following 9 December, when he rejoined. He apparently had little interest in this type of gathering.

Influences and a personal quest

Aesthetically, Nelligan’s first attempts showed the definite influence of certain 19th-century poets of France, particularly Charles Baudelaire and Paul Verlaine. His sonnet “Charles Baudelaire,” published in Le Samedi on 12 Sept. 1896, clearly displays the young poet’s colours in his proclamation of the need for a new kind of poetry that would represent a departure from the writings of most members of the literary circle to which he belonged.

The Classics were dead; behold they wake as well;

Great Reviver, under your pure wings’ spread

A whole age groups. In your cup of verses red,

We drink sweet poison that holds us in its spell.

(English translation by Fred Cogswell in The complete poems of Emile Nelligan, Harvest House Limited, 1983)

Between 29 May 1897 and 21 May 1898, spelling his name Émil Nelligan or Émil Nellighan, he published seven new poems in Montreal’s Le Monde illustré. His verses were sometimes Parnassian but in the manner of the Symbolist poets: like them, Nelligan offered subjective representations of things. As the poet Stéphane Mallarmé had written to fellow poet Henri Cazalis in 1864, Nelligan worked at “painting, not the thing, but the effect it produced.”

For two years (June 1896 to May 1898), Nelligan experimented with and explored the mysteries of modern poetry. Although his readings of Baudelaire, Edgar Allan Poe, Georges Rodenbach, and several minor poets of his time constantly took him in new directions, he succeeded in bringing to light a coherent vision of his tormented mental universe, where he was haunted by the difficulty of living. In “Soir d’hiver,” “La fuite de l’enfance,” and “Le jardin d’antan,” he expresses an inexplicable melancholy and nostalgia for lost childhood. The pre-1900 revisions of his texts testify to his constant attention to the tone and evocative power of words. His language and borrowings from various poets were all changing signposts in a personal quest for the meaning of life and the search for an identity that was undermined by “spleen” and the “dreadful emptiness of things,” as he writes in “Les camélias.”

Rejecting a second profession

Shortly before or after a holiday with his family in Cacouna in July–August 1898, Nelligan apparently made a journey of four to five weeks that took him as far as England. According to Luc Lacourcière, editor of Poésies complètes, 1896–1899, “The reasons for this voyage are not clear. Was he running away or going on an excursion of rest and repose? It is plausible at any rate that his father, wishing to see [his] 18-year-old son working and thus turning away from poetry, had quite simply entrusted him to some captain among his friends.” It seems that, following this adventure, his father found him a job as a “bookkeeper with a coal merchant (or a florist). Nelligan could not force himself to do [the work],” adds Lacourcière. For him, poetry and a second job were incompatible.

Relationships with Robertine Barry and Eugène Seers

On 9 Dec. 1898 Nelligan once more joined the École Littéraire de Montréal and then attended the preparatory meetings for the public soirées that were held at the Château Ramezay between late December and the end of the following May. With the aid of Robertine Barry*, a family friend almost twice his age, he published five new poems in La Patrie between 22 Oct. 1898 and 29 April 1899. Barry had been writing articles on education, literature, and culture for the paper since 1891, under the pseudonym Françoise. The stated or confidential dedicatee of several of Nelligan’s poems, she would assist in disseminating his work until the end of her life.

Meanwhile, Nelligan had also become acquainted with Eugène Seers, who belonged to the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament and managed the printing shop attached to the community’s mother house at 320 Avenue du Mont-Royal Est, four blocks from the Nelligans’ home. Father Seers, known after May 1900 by his pseudonym Louis Dantin, published a small Montreal monthly, Le Petit messager du Très Saint Sacrement, in which appeared religiously inspired poems; Nelligan’s mother had subscribed since the release of its first issue in January 1898. In October it contained her son’s “Les déicides.” Father Seers, whom Nelligan had very likely met during the course of the preceding weeks and would see regularly, became at once his friend, mentor, and publisher. At the time, Nelligan was considering assembling all his verses in a collection for which two provisional titles are known: Récital des anges and Motifs du récital des anges.

New poems and their reception

As well as visiting Father Seers, who encouraged him to compose new poems, which often had a religious theme, Nelligan took part in the four public sessions of the École Littéraire de Montréal held at the Château Ramezay on 29 Dec. 1898 and on 24 Feb., 7 April, and 26 May 1899. He presented some 15 recent works, almost all of them unpublished. On 24 February he recited “Le roi du souper,” “Le perroquet,” “Les Carmélites,” “Nocturne séraphique,” and “Notre-Dame-des-Neiges.” In his account in Le Monde illustré (11 March), E. De Marchy, a little-known critic from France, remembered only “Le perroquet” and mocked it. Deeply hurt by this spiteful review, Nelligan ceased to attend the École’s regular meetings. It appears that, influenced by a few friends, he returned to take part in the two public sessions on 7 April and 26 May. During the last one, Nelligan responded to his detractor by reciting “La romance du vin,” which, according to Dantin, was enthusiastically received by the audience. Yet after this notable performance, the poet disappeared from view.

On 9 August Nelligan was committed to the Asile Saint-Benoît-Joseph-Labre at Longue-Pointe (Montreal), a private psychiatric hospital run by the Brothers of Charity. A number of months passed before his friends learned of this development. He left behind an impressive body of work. In the three years between 1896 and the summer of 1899, he had composed an estimated 170 poems, of which 23 appeared in print.

In the asylum

Several months before Nelligan was committed, his family and friends had observed a deterioration in his mental health. Dantin, who met him several times in 1898 and 1899, described the situation in Les Débats of 17 August 1902:

It is certain that he had this presentiment; and more than once, assailed by some obsessive thought, some dominating idea, feeling invaded by a strange fatigue, he told us in plain language: “I will die mad.” “Like Baudelaire,” he added straightening up…. I have followed closely this labour of inner absorption, simultaneously overexciting and paralyzing all the active faculties, the dark invasion of the dream consuming the soul to the very marrow, and I can say that there is no sight more painful. Lately, Nelligan has been shutting himself away for whole days, alone in his delirium.

What finally drove Nelligan’s parents to take the extreme step of confining him to an asylum is a mystery. No written document by those responsible for the decision gives specific details. In the asylum file (extracts can be found in an article in L’École canadienne), the following information appears: “19 years [old], student; brought in by his parents; under the care of Drs [Michel-Thomas] Brennan and [Joseph-Éloi-Philippe] Chagnon; suffers from mental degeneration, multiple [forms of] insanity.”

With the exception of Nelligan’s family and close friends, this incident initially went unnoticed. From the autumn of 1899 and throughout the following year, few were aware of the fate that had befallen the unfortunate poet since new, previously unpublished pieces continued to appear under his name in newspapers. Paradoxically, his poetry had never been as widely circulated as it was during the first year of his confinement. In March 1900 the École Littéraire launched Les soirées du Château de Ramezay (Montreal), a collection of pieces that had been read during the previous year’s gatherings. Seventeen of Nelligan’s poems, ten of them unpublished, were among them. In September Dantin released Franges d’autel … in Montreal, a small anthology of poems that had appeared in his monthly during the past two years; it included five by Nelligan, one of them unpublished. These two collections spread the poet’s fame more effectively than the 20 or so poems scattered among various periodicals since September 1896.

Dantin edits Nelligan’s work

Dantin had learned of the manuscripts that Nelligan left behind, and in 1902, with the permission of Émilie-Amanda Nelligan, he proposed a lengthy study of the poet’s work in Les Débats (the issues of 17 August–28 September). A few months later, in March 1903, he launched a subscription drive in Montreal’s Revue canadienne for the publication of a book devoted entirely to Nelligan’s œuvre. To entice the reader, he revealed for the first time six new pieces, including “Le vaisseau d’or,” which, in time, became the symbolic expression of the author’s destiny.

At the end of 1902, Dantin apparently began to set up the collection’s works on the Petit Messager’s press. However, on 25 Feb. 1903, after his superiors discovered his secret liaison with Clotilde Lacroix, a married woman, he had to leave his congregation and give up management of the press. The book was only half typeset. He immediately went into exile and settled in Boston, though not before handing over to Nelligan’s mother the annotated manuscript and the full set of sheets he had already printed. She entrusted the entire folder to the Librairie Beauchemin Limitée, which completed the task of printing. The finished book, of which 300 copies were issued, comprised 107 poems; 66 (more than half the collection) were new. The work, divided into ten sections and including the preliminary pages and Dantin’s preface, made up a volume of over 200 pages.

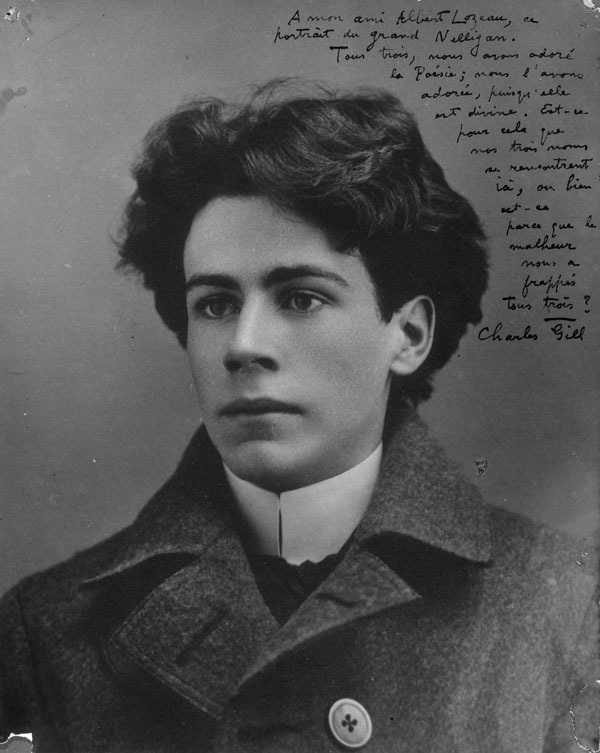

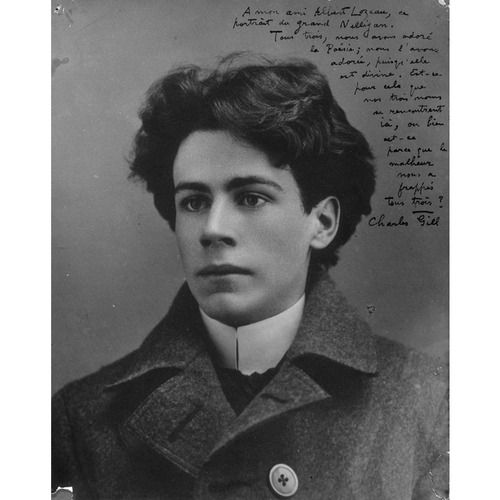

Appearing in February 1904, Émile Nelligan et son œuvre was a genuine revelation and the object of an unprecedented distribution campaign that was orchestrated by the poet’s friends. Albert Laberge*, Anne-Marie Gleason (known as Madeleine), Charles Gill (who had helped Émilie-Amanda Nelligan prepare the collection), Albert Lozeau*, and Robertine Barry published reviews in the Montreal newspapers for which they wrote regularly – La Presse and La Patrie (27 February), Le Nationaliste (6 and 13 March), and Le Journal de Françoise (2 April), respectively. In 1905 news of the book reached Europe, where Charles ab der Halden and Charles-Henry Hirsch in Paris published glowing notices in the January issue of Revue d’Europe et des colonies and in Le Mercure de France on 15 February. A few years later, other unpublished pieces by Nelligan emerged from the drawers of his family and close friends to appear in Le Journal de Françoise and Montreal’s Le Terroir in 1908 and 1909.

Nelligan’s influence

Nelligan’s poetry circulated during the decade following his confinement, and young poets writing in the 1910s became aware of his work. Authors such as Marcel Dugas, Paul Morin, René Chopin, and Guillaume Lahaise (who published under the pseudonym Guy Delahaye) belonged to the new generation of poets who favoured exoticism and were opposed to those who focused on regionalism or rural themes. In 1918 the Montreal review Le Nigog became the mouthpiece of a literary movement that called for a revolution in the arts and championed Modernism in all spheres of knowledge. In this context Nelligan’s body of work was acclaimed as the herald of a new age. Dugas, in particular, was unstinting in his praise of this precursor of modern poetry:

It is true that Émile Nelligan, this handsome Apollo intoxicated with [the work of] Baudelaire, had appeared like a new star. He was hailed as the predestined man who, from among all [others], would bring forth the long-awaited body of work…. [Reading his poems was like] entering a gallery of ancestors, was a dream, an exotic perfume floating above dust that had been celebrated a thousand times. We breathed. Nelligan took us on a wondrous journey on his “Vaisseau d’or,” [which was] rocked on the eternal sea of the poetic dream. We advanced towards a new land, which we greeted with celebratory cries…. We grasped a soul, we read into it, we listened to its pulse. A poet had been born. And this poet did not forget the past and neither did he lock himself away within it…. From [the appearance of] Nelligan[’s] work, and it is a date in the history of Canadian poetry, individualist art was born.

In his turn, the poet Alfred DesRochers*, who was to maintain a long correspondence with Dantin between 1928 and 1939, would claim in the 1920s that he had been influenced by the author of “Le vaisseau d’or.”

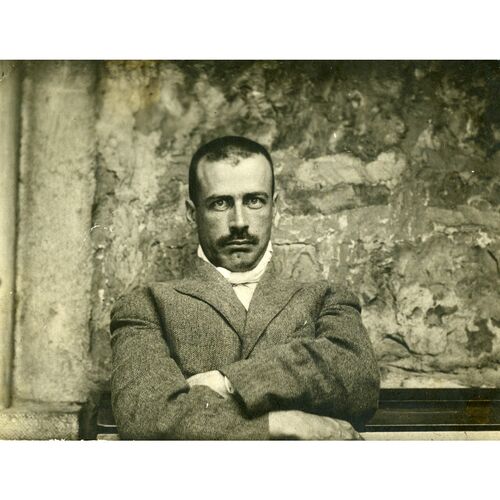

Life at the Asile Saint-Benoît-Joseph-Labre

Nelligan’s body of work had its moment of glory at the very time that its author was isolated from society. At the Asile Saint-Benoît-Joseph-Labre (called the Saint-Benoît retreat from 1923 onward), Nelligan received no visits except from his doctors, family members, and those authorized by the latter, such as Dantin in 1900 and Lahaise between 1906 and 1909. The young patient also aroused the curiosity of doctors such as Georges Villeneuve, Ernest Choquette, and Alcée Tétreault. On 5 April 1904 he copied out his poem “Réponse du crucifix” as a dedication on the copy of Émile Nelligan et son œuvre handed to him by Villeneuve. In December 1909, in the presence of Choquette and Tétreault, he recited perfectly the entire poem “Le naufragé” by François Coppée. After speaking with the poet, Choquette realized, as reported in Le Canada (Montréal) on 24 December, that Nelligan “showed that he was still constantly haunted by literature.” To him it was clear that Nelligan’s state of mind resulted from overly intense literary activity.

Whenever he had the opportunity, Nelligan rewrote and willingly recited poems before an audience he trusted, as visiting members of the community of the Brothers of Charity would confirm. The patient’s docility and shyness were often mentioned.

As the years passed, Nelligan’s family lost several members: on 6 Dec. 1913 his mother, age 57, died of breast cancer; his father, who had paid $20 a month for board and lodging since his son’s admission to the asylum, died of cirrhosis on 11 July 1924; some months later, on 5 May 1925, his sister Gertrude-Freda, 41, also succumbed to breast cancer. That summer only his sister Éva was left, having remained single. She did not have the means to pay for her brother’s board and lodging. On 23 October, Nelligan thus went on public assistance and was transferred to the Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence.

Life at the Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu

Nelligan thus entered a new phase of his life as a patient. He was given better care, especially by an attentive, predominantly female staff, and had greater contact with the outside world. He received numerous visitors and took on light manual labour, such as delivering milk and carrying linen to the laundry. It was noted in his medical file that he performed his tasks well. He was described as shy, helpful, docile, and not very talkative. Guillaume Lahaise, a poet and resident physician at the Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu since 1924, looked after him and saw to his well-being. He supplied Nelligan with books and, on occasion, welcomed his patient to the nearby house that came with his position. In 1905 Lahaise had been moved by the poet’s tragic fate, and the following year, at the beginning of his medical studies, he obtained permission from Mme Nelligan to visit her son; he first went during the winter of 1906–7, next in the summer of 1907, and finally in May 1909. On this last occasion, he had the poet autograph a copy of Émile Nelligan et son œuvre, which he had received in November 1908 from Mme Nelligan. Impressed by the young man’s fervour, in 1907 she had also given him copies of two poems, “Les balsamines” and “Vieille armoire.”

As Nelligan’s fame grew, the circle of those who were interested in him widened throughout the decades. In the interwar period his work was more broadly distributed, especially with the launch of the second (1925) and third (August 1932) editions of Émile Nelligan et son œuvre. In the third edition’s notes, written by the Dominican priest Thomas-Marie Lamarche, the general public learned that the author was still living at the Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu. His poems were taught in schools and colleges and began appearing in anthologies and textbooks. An entry on Nelligan was even included in the dictionary Larousse du xxe siècle en six volumes. On 19 April 1932 the radio station CKAC devoted a one-hour broadcast to him, and on 17 December the Saturday illustrated supplement of La Presse featured a photo that showed him aged but smiling, taken during a visit to the judge and poet Gonzalve Desaulniers in Montreal’s Ahuntsic district.

These events, as well as recent photos of Nelligan that had begun to circulate, aroused the curiosity of the public, journalists, teachers, and new generations of students. Entire classes of pupils, guided by their instructors, filed past the poet at the Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu. Countless numbers came to hear him recite “Le vaisseau d’or” or to obtain an autographed poem or a dedication. Nelligan willingly played along, giving out copies of his own poems or extracts from the writings of French Canadian, French, and English-language poets whom he admired. These impromptu texts, usually reworked, were not without mistakes or inconsistencies, but neither were they lacking in humour, whether intentional or not, and they bore witness to a dynamic interaction between the poet and his visitors and the hospital setting. The last of his known autographed poems, dated 5 April 1941 and written for Gabrielle Desrochers, a Sister of Charity of Providence who had been taking care of him for some time, turned out to be a transcription of his poem “La Bénédictine,” which he retitled for the occasion “La garde malade.”

Final months

In 1941 Nelligan’s health deteriorated. On 1 January he was visited by the family of Émile Corbeil, who since the death of his wife, Gertrude-Freda, had taken over management of her brother’s affairs. On 5 February it was noted in Nelligan’s medical file (extracts can be read in Nelligan, 1879–1941: biographie) that he complained of various pains: “My head is sore. Your ears? Sore. I don’t sleep at night. Noise in my head, in my ears. More than before? About the same.” He was put into isolation, leaving the Saint-Patrice ward for the Saint-Léon infirmary, where he was given a private room. He seemed to be suffering from peribronchitis and cardiovascular trouble. On 5 April it was noted in his file that he had not urinated for two days. On 30 July he was transferred to intensive care. On 21 October Dr Eugène Dufresne observed bladder and prostate problems. On 11 November Nelligan underwent a prostatectomy. Seven days later, in the afternoon, he died – two months before his sixty-second birthday.

So ended the life of Émile Nelligan. He was a poet marked by adversity, who had known moments of grace and brought Quebec poetry into the modern world. Despite the claims of some of his contemporaries, his mental troubles had not been brought on by the writing of poetry; on the contrary, they had been deterred by poetry. He had been called upon to negotiate with irrationality, confront it, and struggle against it to extract from it a body of work that remains a stunning victory over misfortune.

Fame and recognition

Nelligan’s work not only attracted readers and admirers – it also bred poets and other authors. From Guillaume Lahaise to Réjean Ducharme*, and including Albert Lozeau and Alfred DesRochers, he inspired many artists who paid him tribute. His poems, translated into several languages, made a significant impact on the artistic world. His life and work gave rise to original creations in nearly every field: classical music (Jacques Hétu and Maurice Blackburn), opera (Michel Tremblay and André Gagnon*), theatre (Normand Chaurette), cinema (Robert Favreau), and the visual arts (Jean-Paul Lemieux* and Jean-Paul Riopelle*). Singers and composers, among them Claude Léveillée* and Félix Leclerc*, have also been stirred by Nelligan’s writing.

Numerous institutions and public bodies acknowledge the exemplary, emblematic character of Émile Nelligan. In 1974 the Canadian government named him a person of national historic significance. Since 1979 the Prix Émile-Nelligan has been awarded annually to a poet aged 35 or younger. In 1980 the Quebec government named a new electoral riding in the southwest of Montreal Island after him. Many places, streets, parks, monuments, schools, libraries, and private enterprises in the 21st century bear his name. They represent a measure of the fame and recognition accorded the author of “Le vaisseau d’or.”

This biography draws on the work of leading literary historians and experts on Émile Nelligan, such as Yves Garon, Luc Lacourcière, Réjean Robidoux, and Paul Wyczyski. It is based on their authoritative publications in the field of literary history, which are the result of thorough research in several archival fonds. The author compared these sources to come as close as possible to the historical truth. Events that are usually considered legendary or lack reliable written or oral corroboration have been disregarded.

For the 1896–99 period, two critical editions of Nelligan’s work are available: Poésies complètes, 1896–1899, edited by Luc Lacourcière (Montréal et Paris, 1952), remains essential reading; Poésies complètes, 1896–1941, compiled by Robidoux and Wyczynski (Montréal, 1991), expands on that work with updated information and poems unknown in 1952. The complete poems of Émile Nelligan, translated by F. W. Cogswell* ([Montreal], 1983), is the first complete English translation.

The principal sources on the history of the critical reception of Nelligan’s works between 1899 and 1941 are: Wyczynski’s Bibliographie descriptive et critique d’Émile Nelligan (Ottawa, 1973); the author’s Émile Nelligan: les racines du rêve (Montréal et Sherbrooke, Québec, 1983) and “La réception de Nelligan de 1904 à 1941,” Protée (Chicoutimi [Saguenay, Québec]), 15 (hiver 1987): 23–29; and Annette Hayward, La querelle du régionalisme au Québec (1904–1931): vers l’autonomisation de la littérature québécoise (Ottawa, 2006).

The manuscript sources consulted are mainly from the Émile Nelligan fonds (MSS82) held at the Centre d’arch. de Montréal de Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec. In the Nelligan-Corbeil collection (MSS82-S1) within that fonds, there are photos and manuscripts that Louis Dantin did not use for Émile Nelligan et son œuvre (Montréal, 1904). A photographic edition of the manuscripts, which were unpublished until Lacourcière’s work was released, appears in Poèmes autographes ([Saint-Laurent [Montréal], 1991), edited by Paul Wyczynski. In addition, manuscripts from Nelligan’s years in the asylum (1899–1941), located in the Nelligan fonds, formed the basis for the author’s article cited above, for his Poèmes et textes d’asile, 1900–1941 (Montréal, 1991), and for the version revised and expanded by André Gervais with the author’s collaboration ([Montréal], 2006).

Since Nelligan and his family left no personal writings such as letters or memoirs, it is necessary to rely mostly on printed sources (books, studies, and articles in magazines and newspapers) that appeared during the poet’s lifetime. The accounts of those closest to him must be referenced with the greatest caution, as Lacourcière points out in “À la recherche de Nelligan,” in Émile Nelligan: poésie rêvée et poésie vécue (Ottawa, 1969) and in Essais sur Émile Nelligan et sur la chanson populaire, edited by Gervais ([Montréal], 2009). For this biography, only events corroborated by more than one source have been considered. This is particularly true of the evidence provided by the poet’s sister Éva Nelligan and her cousin Charles-David Nelligan, who agree on their relative’s presumed trip to England, which can be dated to 1898, as Lacourcière asserts in Poésies complètes, 1896–1899.

To establish with greater certainty the year that Nelligan met Father Eugène Seers, the author relied on Garon’s doctoral thesis, “Louis Dantin, sa vie et son œuvre” (Univ. Laval, Québec, 1960), as well as his article “Louis Dantin, précurseur et frère d’Émile Nelligan” in Émile Nelligan: poésie rêvée et poésie vécue. In the latter, Garon shows conclusively that their first significant contact would have occurred in the autumn of 1898 rather than April 1896 as several literary historians have written. In Émile Nelligan: biographie ([Montréal], 1999), a revised edition of his Nelligan, 1879–1941: biographie (Montréal, 1987), Wyczynski concurred with this view even though he, like his predecessors, had first placed this meeting in 1896.

Wyczynski’s Album Nelligan: une biographie en images ([Montréal], 2002) captures a complete iconographic archive for Nelligan. Among the notable items reproduced are a facsimile of the poet’s baptismal certificate (dated 25 Dec. 1879), the famous photo taken in the Laprés et Lavergne studio in Montreal, J.-P. Lemieux’s oil painting Hommage à Nelligan (1971–72), and one of J.-P. Riopelle’s 16 lithographs from Lied à Émile Nelligan (n.p., 1979). Much of the original material comes from the Paul Wyczynski fonds (P19) held at the Centre de Recherche sur les Francophonies Canadiennes in Ottawa.

Works that do not meet scholarly standards and are closer to fiction or a novel than a historical account are not included in this bibliography. As well, certain books, such as Bernard Courteau’s Nelligan n’était pas fou! (Montréal, 1986) and Yvette Francoli’s Le naufragé du “Vaisseau d’or”: les vies secrètes de Louis Dantin ([Montréal], 2013), have been ignored. Supposedly objective, they contain numerous factual errors and incorrect dates, and convey false information. Robidoux’s Connaissance de Nelligan ([Saint-Laurent], 1992) and the article “Dantin et Nelligan au piège de la fiction: Le naufragé du ‘Vaisseau d’or’ d’Yvette Francoli” by Annette Hayward and Christian Vandendorpe in @nalyses: rev. de critique et de théorie littéraire (Ottawa), 11 (printemps–été 2016), no.2: 232–327, provide a good overview of this issue.

Ancestry.com, “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin Coll.), 1621–1968,” Basilique Notre-Dame (Montréal), 21 nov. 1941: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091 (consulted 3 Feb. 2023). Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de l’Estrie (Sherbrooke), P6; Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE601-S52, 25 déc. 1879. Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), R233-34-0, Que., dist. Montreal West (106), subdist. St Laurent Ward(c): 55–56; R233-35-2, Que., dist. Montreal (90), subdist. St Laurent Ward (l): 14. Le Canadien (Québec), 28 déc. 1892. Les Débats (Montréal), 17 déc. 1899; 14 janv., 24 juin, 15 juill. 1900. Le Matin (Montréal), 17 nov. 1923. La Patrie (Montréal), 16, 23 sept., 16 déc. 1899; 18 sept. 1937; 24 juill. 1949. La Presse (Montréal), 23 nov. 1895, 17 déc. 1932, 19 nov. 1941. Maurice Blackburn, Trois poèmes d’Émile Nelligan: chant et piano ([Québec, 2014]). Arthur de Bussières, “Les Bengalis” d’Arthur de Bussières avec des textes inédits, Robert Giroux, édit. (Sherbrooke, 1975). Le Canada ecclésiastique, almanach annuaire du clergé canadien (Montréal), 1911. Normand Chaurette, Rêve d’une nuit d’hôpital (play, Montréal, 1980). Louis Dantin, Émile Nelligan et son œuvre, Réjean Robidoux, édit. (Montréal, 1997); Essais critiques, Yvette Francoli, édit. (2v., [Montréal], 2002), 1. Guy Delahaye, Œuvres parues et inédites, Robert Lahaise, édit. (LaSalle [Montréal], 1988). Dictionnaire complet illustré de la langue française, P[ierre] Larousse et Sylva Clapin, édit. (Montréal, 1928). Marcel Dugas, Littérature canadienne: aperçus (Paris, 1929). Paul Dumas, “Un médecin-psychiatre qui avait été poète, Guillaume Lahaise et son double, Guy Delahaye,” L’Union médicale du Canada (Montréal), 100 (1971): 321–26. Olivier Durocher [Marie Timmins, dite Sœur Marie-Henriette-de-Jésus], Un ami intime de Nelligan, Lucien Rainier (abbé Joseph-Marie Melançon): l’homme et l’œuvre (Montréal, 1966). L’École littéraire de Montréal, sous la dir. de Paul Wyczynski (Montréal, 1972). L’École littéraire de Montréal: procès-verbaux et correspondance (et autres documents inédits sur l’école), Réginald Hamel, édit. (2v., Montréal, 1974). Écrits du Canada français (Montréal), 44–45 (1982), numéro spécial intitulé Louis Dantin: études, témoignages, correspondance. Émile Nelligan, J.-N. Samson, édit. (Montréal, 1968). Émile Nelligan (1879–1941): cinquante ans après sa mort, sous la dir. de Yolande Grisé et al. ([Saint-Laurent], 1993). Michel Foucault, History of madness, ed. Jean Khalfa, trans. Jonathan Murphy and Jean Khalfa (London and New York, 2006). André Gagnon, Monique Leyrac chante Nelligan (sound recording, Montréal, 1976). André Gagnon et Michel Tremblay, Nelligan, un opéra romantique (Montréal, 1990). C.-H. Grignon, “Louis Dantin dit le vieillard cacochyme,” Les Pamphlets de Valdombre (Sainte-Adèle, Québec), 2 (1938): 273–84; “Marques d’amitié,” Les Pamphlets de Valdombre, 2: 173–76; Un homme et son péché, Antoine Sirois et Yvette Francoli, édit. (Montréal, 1986). Jacques Hétu, Les abîmes du rêve (musical work, 1982); Les clartés de la nuit (musical work, 1972); Les illusions fanées (musical work, 1988). Robert Lahaise, Guy Delahaye et la modernité littéraire (LaSalle, 1987). Larousse du XXe siècle en six volumes, sous la dir. de Paul Augé (6v., Paris, 1928–33), 5: 44. Albert Lozeau, Œuvres poétiques complètes, Michel Lemaire, édit. ([Montréal], 2002). Stéphane Mallarmé, Correspondance, Henri Mondor et Jean-Pierre Richard, édit. (11 tomes en 12v., Paris, 1959–85), 1 (1862–1871). Jacques Michon, “La perte du corps certain: analyse du ‘Vaisseau d’or’ de Nelligan,” Incidences (Ottawa), nouv. sér., 4 (1980), no.1: 67–77. Nelligan, réalisation de Robert Favreau, scénario de Robert Fravreau, Aude Nantais, Claude Poissant et J.-J. Tremblay, images de Guy Dufaux (film, [Montréal], 1991). Marcel Séguin, “Entretiens sur Émile Nelligan,” L’École canadienne ([Montréal]), 32 (1956–57): 665–71. Les soirées du château de Ramezay de l’École littéraire de Montréal, Micheline Cambron et François Hébert, édit. ([Saint-Laurent], 1999).

Cite This Article

Jacques Michon, “NELLIGAN, ÉMILE (Émil Nelligan, Émil Nellighan, Émil Nélighan, Émile Kovar),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nelligan_emile_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nelligan_emile_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacques Michon |

| Title of Article: | NELLIGAN, ÉMILE (Émil Nelligan, Émil Nellighan, Émil Nélighan, Émile Kovar) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | April 24, 2025 |