Source: Link

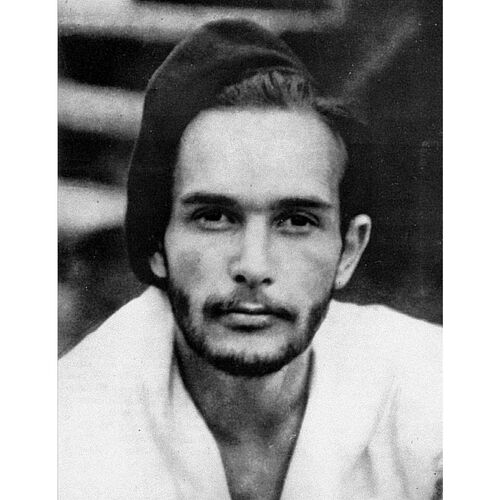

GARNEAU, DE SAINT-DENYS (baptized Hector St-Denys, he usually signed de St-Denys and, occasionally, de Saint-Denys), poet; b. 13 June 1912 in Montreal, son of Paul Garneau, a banker, and Hermine Prévost; d. unmarried 24 Oct. 1943 at Sainte-Catherine (Sainte-Catherine-de-la-Jacques-Cartier), Que., and was buried four days later in the parish cemetery.

Background and family circumstances

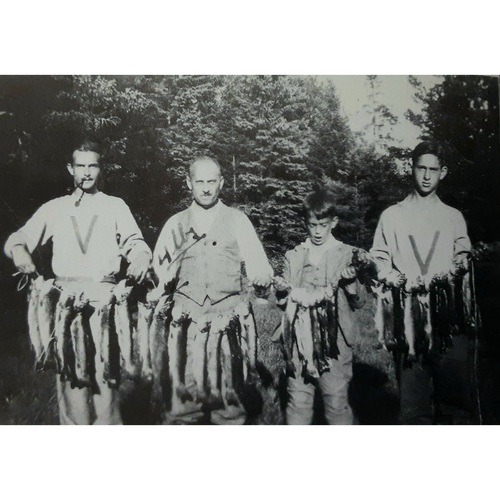

De Saint-Denys Garneau was the eldest son of a family of four children. His name can be traced back to his maternal ancestor, Nicolas Juchereau* de Saint-Denis, who was ennobled by Louis XIV in 1692. Very rare in the 21st century, it is similar to the names of several of his mother Hermine’s relatives, including her brother de St-Denys, who dropped the aristocratic “de” before he married. Garneau’s family belonged unquestionably to the French Canadian elite. His maternal grandfather, Oscar Prévost*, had founded a cartridge factory in Quebec City and left his children an inheritance that allowed Hermine to acquire two properties: a principal dwelling in Westmount and a seigneurial manor at Sainte-Catherine, near Quebec City. The manor was built by Conservative senator Antoine Juchereau-Duchesnay, Garneau’s maternal great-grandfather, in the mid 19th century. Although they had lived in the Westmount residence since 1913, the family’s material circumstances were more difficult than they appeared, partly because of Garneau’s father’s deafness, which led to the loss of his job as a manager at the Royal Bank of Canada. In 1916 the family moved into the manor house at Sainte-Catherine, where Paul tried in vain to work the land and manage the forested areas. After a brief stay in Quebec City, the Garneaus returned to Westmount in 1923. Paul found modest employment in Montreal as an accountant at the Quebec Liquor Commission.

Education, art, and relationships

Like his two brothers and sister, de Saint-Denys was educated at Montreal’s classical colleges: initially at the Collège Sainte-Marie, and then at Loyola College and the Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf, after which he returned to Sainte-Marie. During his first years of classical studies, he took courses in painting on the side at the newly established School of Fine Arts of Montreal, wrote poems in the Romantic vein, and participated in various intellectual activities. In 1928 he attended gatherings at the Cercle Crémazie, whose members met at the home of André Laurendeau* to discuss modern literature. As an adolescent, he also worked on student magazines and was noted for his humour and ready wit. At the time he hesitated between two vocations: painting and poetry. He ruled out any other kind of career very early on and threw himself into art with an intensity of ambition then unusual in French Canada. Because of health problems, however, he was never to complete his classical studies. In the autumn of 1931 he was diagnosed with a heart lesion, which compelled him to avoid overexerting himself physically and intellectually. He fell behind academically, and two years later, when he was enrolled in the penultimate year of classical studies (Philosophy I), he abandoned his schooling permanently on the advice of his doctor.

As a young adult Garneau developed friendly and romantic relationships of which there are traces in his correspondence. In the spring of 1931, for example, he wrote passionate letters to Suzanne Manseau. Shortly thereafter, he told Laurendeau that he had had a relationship worthy of a novel with one Lucie Auger, an older woman. However, the intensity (and brevity) of his emotional fervour is best revealed in his letters to Gertrude Hodge, written in the autumn of 1933.

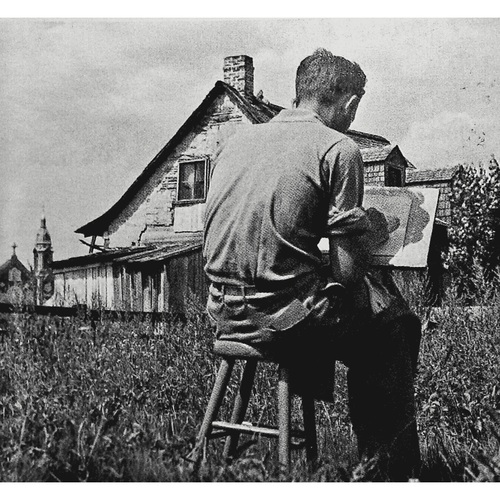

No longer attending school, Garneau had a great deal of time to devote to writing and painting. He produced numerous landscapes in the vicinity of the manor at Sainte-Catherine, where he spent his summers and sometimes stayed during the winter. It was from there that he wrote most of his correspondence. He also kept a journal, which from 1935 onward became the very heart of his work as a writer: he used it to copy out his poems and deepen his reflections on art, music, and poetry; he practised describing landscapes and individuals; he wrote outlines of short stories and ideas for novels; he recorded numerous notes and impressions from his reading; he observed his progress and frequently analysed his style.

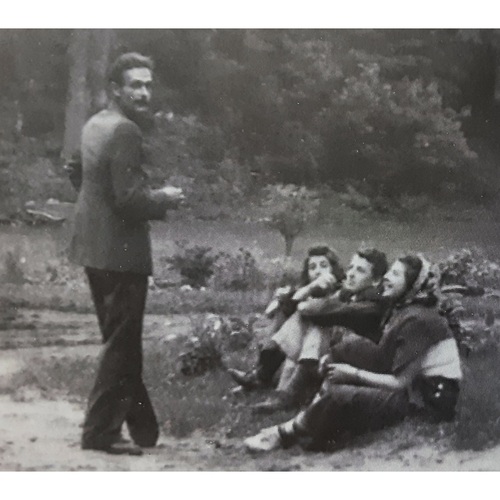

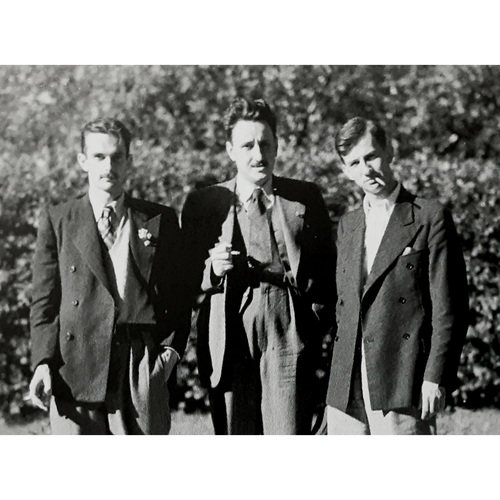

With old college friends, including Jean Le Moyne*, Claude Hurtubise*, and Robert Élie*, Garneau participated in the blossoming of Montreal’s intellectual life in the mid 1930s. They met regularly at a restaurant or elsewhere in town, attended exhibitions, and got together every Sunday to listen to the New York Philharmonic Orchestra’s concert broadcast on Radio-Canada. Music was then an important part of Garneau’s life. By listening to and commenting on the works of Debussy and Beethoven in particular, he was able to refine his taste for what he considered imperfection and a degree of abstraction, which coloured his own manner of writing. On 22 March 1935 he entered in his journal this sentence, which was to prove prophetic: “I am moving away from facile, flowing lyricism, which gets carried away by its own momentum: I am detaching myself from words.” This rejection of his youthful Romanticism signals the emergence of the Garneau who would become known through the poems of his mature period: those written between the ages of 23 and 26.

La Relève

Although Garneau honed his style and ideas in his journal and letters, far from the public eye, he was not isolated during this period. He dreamed of travelling, as did, for example, Le Moyne, and he pursued his education, independently setting himself a course of reading in order to acquire a true classical culture. He was very interested in the recently founded Roman Catholic review La Relève, established in Montreal in 1934 by two former students of the Collège Sainte-Marie, Robert Charbonneau and Paul Beaulieu. His close friends played a leading role on the journal, especially Hurtubise, who soon became editor-in-chief. For a while Garneau attended meetings of the editorial team, who sought his collaboration. He published relatively minor pieces in La Relève before releasing a small number of poems in the journal in 1936 and 1937. Remaining somewhat in the background, he nonetheless found in the review an intellectual milieu favourable to his poetic talents and, in addition, a cultural, spiritual, and philosophical perspective. It is hard to imagine him flourishing if he had not found such an environment, in which he was encouraged to publish his work.

Garneau identified with the La Relève group more than with any other, sharing with its organizers similar ideas on the need for spiritual renewal in an era marked by the rise of ideologies and haunted by the economic crisis of 1929. Like them, he fell under the influence of Christian personalism as expressed by French thinkers such as Jacques Maritain and Emmanuel Mounier, whose views were often echoed in the publication. The spiritual revolution to which Garneau and his Catholic friends aspired was expressed less as a political agenda than as a complete remaking of society centred on the unity of the human being. It was also rooted in a new thirst for universal culture, both the classical taught by the schools and more modern forms, which up until then were a cause for concern for French Canada’s church. More generally, however, the whole issue of spiritual disarray and the quest for self, which were such decisive influences on Garneau’s poetry, found fertile ground in La Relève, in the opposition between universal humanity and reductive definitions of the individual that are limited to national identity or alienation in a materialistic and capitalist society.

Although Garneau stayed out of public debates, he occupied a unique place in the group of young Montreal intellectuals: he was the one poet among the review’s contributors. Only Élie was passionate about poetry but wrote none himself. Even though the periodical discussed certain poets, it published no poems but those written by Garneau. The same can be said of the literary landscape of the period generally: between 1935 and 1938, when Garneau was composing his work, there was no dedicated space for poetic expression in French Canada. No publisher was interested in the genre. Furthermore, Garneau did not seek to become part of a Quebec literary movement. He never quoted his own grandfather, the poet Alfred Garneau (son of the historian François-Xavier Garneau*), nor did he identify with any French Canadian poets. In fact, he had no desire to mix with writers outside the La Relève group, any more than he cared to associate with painters.

Despite his aloofness Garneau followed French Canadian literary currents from afar, thanks to the critic Maurice Hébert (father of poet and novelist Anne Hébert* and a cousin of his mother). In this way he discovered À l’ombre de l’Orford, published in 1929 by Alfred DesRochers*, “the first real Canadian poet I have read,ˮ as he wrote in a letter to Hurtubise on 16 July 1931. Garneau was sufficiently appreciative of Claude-Henri Grignon*’s work to publish a review of his collection of short stories, Le déserteur et autres récits de la terre (Montréal, 1934), in the October 1934 issue of La Relève. He was especially interested in writers from abroad, such as Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Maurice Maeterlinck, and Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz, and in contemporary poets, including Eugène Grindel (known as Paul Éluard), Jules Supervielle, and Pierre Reverdy, whose influence can be detected in the spare, impersonal verse favoured by Garneau. However, just as the influence of Baudelaire or Verlaine can be easily recognized in the compositions of Émile Nelligan, Garneau’s poetry, on the other hand, is his alone, written as if he had no master. It would not have occurred to him to imitate the authors whose work he discussed, as can be seen in his lengthy four-part commentary on the French regionalist novelist Alphonse de Châteaubriant, published in La Relève in 1935–36.

Regards et jeux dans l’espace

In March 1937 Garneau, aged 24, suddenly decided to emerge from his solitude. In a letter to Hurtubise written at the end of May the previous year, he had announced an exhibition of his paintings (which never took place) and then, thanks to help from his parents, he self-published a collection of 28 poems, Regards et jeux dans l’espace, in Montreal. “This book is truly my own,ˮ he wrote to Laurendeau on 18 March 1937. He kept a close eye on the materials used in producing the volume, the placement of the graphics, and the page layout, and was particularly aware of having written a book unlike any other in the province of Quebec or elsewhere. The choice of free verse had a lot to do with its uniqueness. Nevertheless, it was not a matter of his breaking with the traditional practice of regular verse in the name of some sort of modernity: he abandoned fixed forms and, in particular, the alexandrine – not, in Verlaine’s words, to do away with eloquence but simply because he felt unable to be himself in verse of such grandeur. Regards et jeux dans l’espace opens with a poem that makes lack of support the condition by which this “me,ˮ freed from the usual boundaries, is able to emerge. To the first line, “I am far from easy sitting on this chair,” the last line responds, “It is there in suspension that I am at rest.ˮ The whole collection reads like a very elaborate account of this “I”: it repeatedly re-poses itself in search of itself, is lost and found, unified and duplicated, moving from a childhood game to lucidity, which is summed up in the title of the section “De gris en plus noir” and culminates in the final poem, “Accompagnement”: “I walk beside a joy / A joy that is not mine / A joy of mine that is not mine to enjoy.”

A thousand copies of Regards et jeux dans l’espace were printed, and it was placed on consignment with numerous Montreal bookshops and advertised in the daily Le Devoir. The critics were generally enthusiastic, with the exception of the polemical novelist Grignon, who, in an article published on 26 March in Saint-Hyacinthe’s En avant!, mocked Garneau’s pretentions and, in particular, attacked his decision to write in free verse. It is not known to what extent the appraisal truly hurt him, only that in the weeks following the book’s publication, the surprising confidence shown by Garneau at the start of the year collapsed, perhaps because of Grignon’s article but more likely because Garneau realized that his collection was selling poorly. According to Laurendeau, by the autumn Garneau had sold only 37 copies. He went from euphoric to discouraged. He accused himself of being an imposter, of playing at being a poet and therefore lacking sincerity, which was for him an essential quality in any art form. His disavowal was final. He went so far as to burn copies that were lying around in the basement of the Westmount family home. He also recovered some of the copies left with booksellers; he no longer wished to sell them. In this fashion, he withdrew his book from circulation and, with a heavy heart, retreated from society, taking refuge at Sainte-Catherine.

Despite this setback, Garneau agreed to make a trip to France, which had been planned for several months. He left Montreal on 2 July with Le Moyne, but what was intended to have been a year’s stay soon turned into a nightmare. The letters written from Europe are among Garneau’s darkest, and in them he offered no explanation for the specific causes of his distress. What is known is that, wanting to flee Paris, he went to Lourdes and then to Chartres, where he experienced his only moment of grace. He relapsed and decided to return to Quebec barely ten days after setting foot in France.

In 1937 Garneau reached a decisive, and dramatic, turning point. From January to March he had high hopes. He threw himself into publishing ventures as though he were embarking on his real work: he glimpsed the possibility of publishing other books in the wake of Regards et jeux dans l’espace, and even dreamed of launching the latter in France. Six months later, however, he wanted nothing more to do with his collection. “I no longer like writing,ˮ he confided to Élie on 30 December, announcing that he never wanted to publish again. In fact, even though he continued to write in his journal and kept up correspondence with his friends as before, Garneau would not release another work except the article “Les cahiers des poètes catholiques,” a commentary on the review of the same name, which appeared in the February 1938 issue of L’Action nationale (Montréal). Although his friends sent him many invitations, he firmly declined them all.

Final years

At 25 Garneau found himself at an impasse. The only life he had ever seriously considered – that of a poet – had become impossible. As for the life of a painter, he had given that up some time before, although this decision did not prevent him from producing occasional small works, almost always landscapes. On 2 Jan. 1941 he wrote with irony to Anne Hébert that the painter Louis Muhlstock had “predicted a brilliant future” for him. Garneau had in fact abandoned any artistic ambition and had settled for drawing notecards for family members. They continued to support him, but in his journal entry of 30 Jan. 1938 he himself wondered, “Have I [chosen] an empty vocation?” He could no longer endure the company of others and suffered, as he wrote in a letter to Le Moyne on 27 Oct. 1937, from social “phobia.” Even the idea of receiving communion among the village parishioners caused him to panic. Garneau confided in a spiritual adviser but to no end. For him, writing was no longer anything but a mistake, a sin of pride. His letters and journal reveal his distress. Paradoxically, it was when he saw the impossibility of writing that he created some of his most original and successful work. This was especially the case with the short piece he composed in his journal between January and April, entitled “Le mauvais pauvre va parmi vous avec son regard en dessous” [The poor wretch goes amongst you with his eyes downcast], which reads like a striking self-portrait. He depicts the impoverished man as an imposter who, if he wants to stop lying to himself and others and express his essential self, has no choice but to shed everything that is only a false impression: his clothes, his skin, and also part of his skeleton. In the end just his backbone remains, the ultimate expression of self, “the only thing certain not to lie.”

Henceforth settled permanently at Sainte-Catherine, Garneau was more idle than ever. He had always lived in his parents’ house, he had never worked outside it, and he had no intention of doing so, as can be seen on the form he filled out in August 1940 as a result of the passage of the National Resources Mobilization Act. He indicated that he was “supported by [his] father.” “Current employment? None.… Usual employment? None.… What other work can you do adequately? None.… Is there any trade that you would like to learn? No.” It appears Garneau was both an eternal adolescent and an early retiree. He gradually severed all ties with every intellectual circle. His Montreal friends visited him less and less frequently as their own family and professional obligations increased. In contrast, Garneau had no engagements: he still had no job and relied on his parents, who had come to join him at Sainte-Catherine in 1941 because they were so worried about his physical and mental state. In a letter dated 25 Sept. 1942, he explained to his brother Paul (who, on October 2, would receive the Distinguished Service Order for his role as staff captain in the August raid on Dieppe, France) that he was exempt from military service for reasons of health – his “rheumatism and the resulting heart condition.”

With no obligations of any kind, Garneau spent his days looking after the house and grounds, drawing notecards that he distributed to family members, walking or skiing, sometimes alone, sometimes with neighbours. When there were guests at the manor, he would occasionally isolate himself further and sleep in a tent erected for the summer on an island in the middle of the Rivière Jacques-Cartier. After setting out in a canoe to retrieve the tent, which had been lent by his uncle St-Denys Prévost, he died of a heart attack on 24 Oct. 1943. His body was not found until the next day, half lying in a stream, a few steps from the river.

Posthumous publications and posterity

Garneau’s friends offered numerous tributes and subsequently undertook to publicize his poems. In 1949 they released a new edition entitled Poésies complètes: Regards et jeux dans l’espace, les solitudes. Comprising 70 previously unpublished compositions, it reveals the extent of Garneau’s work; henceforth many considered him the greatest modern poet of French Canada. Praise, however, was accompanied by an uneasiness: several regretted that Garneau had been so little known in his lifetime. His destiny as a solitary, misunderstood poet became the symbol of a collective misery. Friends discovered the depth of his private tragedy when his parents gave them his journals, having first torn out numerous pages, now lost forever. They compiled extracts and published them in Montreal in 1954 as Journal, with a preface by Gilles Marcotte. The life of the poet then assumed an importance greater than his work. Several readers, including the Swiss critic Albert Béguin, kindled the legend that Garneau had committed suicide. His friend Le Moyne attacked the stifling nature of French Canadian society in an accusatory text published in his Convergences (Montréal, 1961), which began with the declaration: “I cannot speak of Saint-Denys-Garneau without anger. Because we killed him.” The author of Regards et jeux dans l’espace was thus portrayed as the victim of a Jansenist, hypocritical society, forced to remain silent. In the eyes of those who took part in the Quiet Revolution, he was the embodiment of the frail, unhappy writer, the symbol of those affected by a rigid world that the new generation wanted to eradicate. It was not until the critical edition Œuvres was published by the poet Jacques Brault and Father Benoît Lacroix (a friend of Garneau’s parents) in 1971 that the public returned to Garneau’s work without reducing it to the tragic biography of its author.

It is still difficult to dissociate the strength of de Saint-Denys Garneau’s work from the ferocity with which he rejected his poetry and turned his back on literature. This act, unparalleled in literary history, has lost nothing of its enigmatic power. How did such a gifted poet who was so deeply involved in the adventure of language manage to detach himself from it so radically? The admiration for Garneau’s work and its influence on contemporary poets and prose writers, from Pierre Nepveu to Hélène Dorion and including Pierre Vadeboncoeur* and André Major, no doubt owe something to the farewell to literature personified by the author of Regards et jeux dans l’espace. In the words of Brault’s Chemin faisant: essais, by going beyond “the word toward silence,” Garneau had “the courage to risk everything.”

This text is based on the author’s book De Saint-Denys Garneau: biographie ([Montréal], 2015). It contains the list of documentary sources consulted for this biography. The author published all the poet’s known letters in De Saint-Denys Garneau: lettres ([Montréal], 2020); excerpts from Garneau’s correspondence are drawn from this work. References to his diary can be found in his Journal (1929–1939) (Québec, 2012).

Garneau’s writings have been the subject of several publications, including: Lettres à ses amis (Montréal, 1967); Œuvres en prose, Giselle Huot, édit. ([Saint-Laurent (Montréal)], 1995); Poèmes et proses (1925–1940: avec des inédits (textes et illustrations), Giselle Huot, édit. (Montréal, 2001); and Poésies complètes: “Regards et jeux dans l’espace,” “Les solitudes,” introd. par Robert Élie (Montréal et Paris, 1949). An English translation of Garneau’s poetry was published in 1975 as Complete poems of Saint Denys Garneau, trans. John Glassco (Ottawa).

Ancestry.com, “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin coll.), 1621–1968,” Cathédrale St-Jacque-le-Mineur (Montréal), 14 juin 1912: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091 (consulted 3 Feb. 2023). Le Devoir (Montréal), 5 avril 1937. Albert Béguin, “Réduit au squelette,” Esprit (Paris), no.220 (1954): 640–49. Roland Bourneuf, Saint-Denys Garneau et ses lectures européennes (Québec, 1969). Jacques Brault, “Saint-Denys Garneau 1968,” in his Chemin faisant: essais (Montréal, 1975), 107–9. “De Saint-Denys Garneau, le poète qui a mené le Québec à la modernité littéraire: la vie et l’œuvre de Saint-Denys Garneau racontées par Michel Biron,” dans Aujourd’hui l’histoire, réalisation de Mathieu Beauchamp (émission de la Société Radio-Canada, Montréal, 6 nov. 2020; available at ici.radio-canada.ca/ohdio/premiere/emissions/aujourd-hui-l-histoire/segments/entrevue/208156/saint-denys-garneau-poete-michel-biron). Alfred DesRochers, À l’ombre de l’Orford (Sherbrooke, Québec, 1929). Giselle Huot, “L’aventure artistique du peintre de Saint-Denys Garneau,” Mens (Montréal), 4 (2003–4): 211–71. Antoine Prévost, De Saint-Denys Garneau, l’enfant piégé: récit biographique ([Montréal], 1994). Jacques Roy, L’autre Saint-Denys Garneau: suivi de cinq lettres inédites de Saint-Denys Garneau (Québec, 1993). Statistics Can., “Searches of the National Registration File of 1940,” de St-Denys Garneau, 19 Aug. 1940: www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/93C0006 (consulted 8 Oct. 2021). Paul Verlaine, Art poétique, in his Jadis & naguère (Paris, 1884), 23–25.

Cite This Article

Michel Biron, “GARNEAU, DE SAINT-DENYS (baptized Hector St-Denys) (de St-Denys),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 23, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/garneau_de_saint_denys_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/garneau_de_saint_denys_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michel Biron |

| Title of Article: | GARNEAU, DE SAINT-DENYS (baptized Hector St-Denys) (de St-Denys) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | February 23, 2026 |