Source: Link

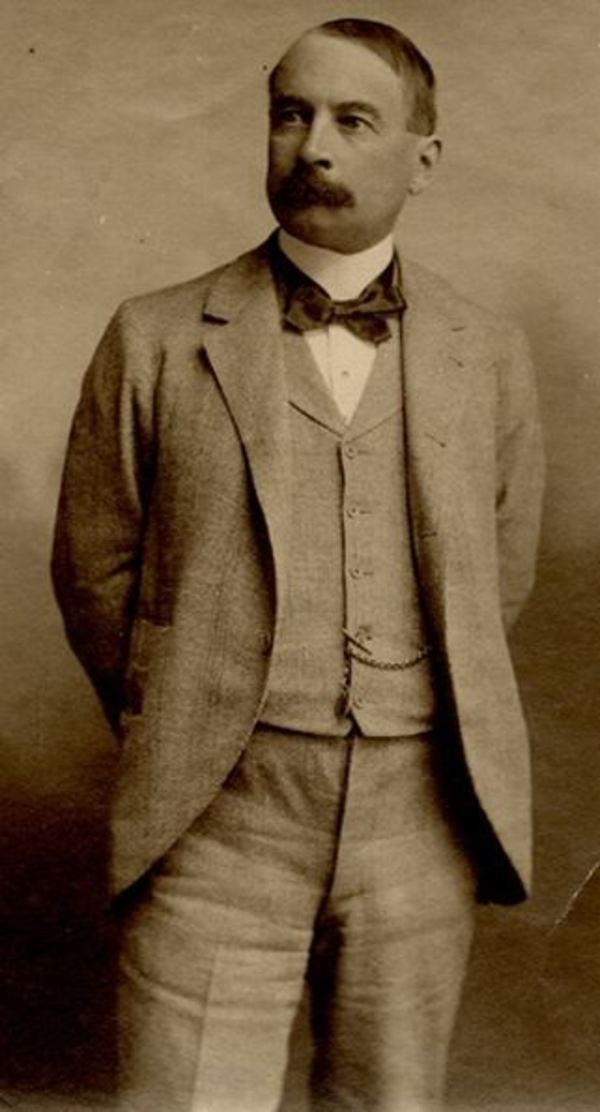

PACAUD, ERNEST (baptized Philippe-Olivier), lawyer, newspaper editor and publisher, and office holder; b. 25 Aug. 1850 in Trois-Rivières, Lower Canada, son of Philippe-Napoléon Pacaud*, a notary, and Clarice Duval; m. there 23 Aug. 1876 Marie-Louise Turcotte, an under-age daughter of the late Joseph-Édouard Turcotte*, and they had six children; d. 19 April 1904 at Quebec and was buried in Notre-Dame de Belmont cemetery.

Ernest Pacaud came from a family of Patriotes, three of whose members had taken part in the 1837 uprising. His father, then a notary in Saint-Hyacinthe, had fought at Saint-Denis and Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu and had been imprisoned in the Montreal jail. He had later moved to Saint-Norbert d’Arthabaska (Norbertville). Through unknown circumstances, however, Ernest was born in Trois-Rivières, where he is believed to have attended an English elementary school – probably the French and English academy run by G. W. Lawler. On 4 Sept. 1861 he began his classical studies at the Séminaire de Nicolet, and he completed them on 16 May 1868. He was then articled as a clerk to his uncle Édouard-Louis*, a lawyer in Arthabaskaville (Arthabaska), which was the principal town of the Arthabaska district and had a population of about 800. The Pacaud family, with notary Philippe-Napoléon and his brothers Édouard-Louis, merchant Charles-Adrien, and businessman Georges-Jérémie, exercised considerable political influence in the district. Their houses were centres of Rouge ideas. At the home of his lively uncle Édouard-Louis, the gathering place for members of the local élites, Ernest met Wilfrid Laurier*, who was eight years his senior; the boundless admiration he felt would develop into a firm friendship over the years. It was he who persuaded Laurier to run for Drummond and Arthabaska in the 1871 provincial election. Laurier would later observe that Ernest “changed my life and fixed it upon the unfailing object of all my thoughts and aspirations.” According to Charles Langelier*, during the Fenian invasion of 1870 [see John O’Neill*] Pacaud set aside his legal work and joined the militia as aide-de-camp to Lieutenant-Colonel Louis-Charles-Auguste Lefebvre de Bellefeuille, brigade major for the district of Saint-Hyacinthe. This service would earn him the medal awarded by Queen Victoria in 1899 to veterans of the 1866 and 1870 Fenian raids.

Pacaud was called to the bar on 8 July 1872 and quite naturally decided to set up in Arthabaskaville. Practising on his own, he argued cases before all the courts. He was undeniably successful – around 1877 he estimated his annual income at approximately $4,000 – but his true passion was politics. He played an important role in the rise of Laurier. At the time of the Pacific Scandal [see Sir Hugh Allan*], he encouraged him to take the plunge into federal politics under the leadership of Alexander Mackenzie*. The federal election of February 1874 coincided with a provincial by-election in Drummond and Arthabaska. Laurier ran for the House of Commons and Pacaud for the Legislative Assembly. The two men conducted a strenuous campaign side by side. Laurier was elected, but Pacaud lost to William John Watts. He was at Laurier’s side again in the fall of 1877, when his friend went down to defeat in Drummond and Arthabaska and then won a resounding victory in Quebec East.

These were decisive years. In Arthabaskaville Pacaud had his initiation into politics, establishing contacts and sometimes friendships with future leaders of Quebec society. Among these associates of his uncle and Laurier were Joseph Lavergne, Louis Fréchette, Laurent-Olivier David*, Joseph-Xavier Perrault, Charles Langelier, Lawrence John Cannon*, Hector Fabre, and François-Xavier Lemieux*. He also discovered his true vocation: journalism. On 5 Oct. 1877, at Laurier’s urging and his, some of their friends launched Le Journal d’Arthabaska. It began as a pro-Laurier election sheet but, with Pacaud’s enthusiasm and federal government contracts, it became a militant regional newspaper. Journalism is “a thankless profession, to be sure,” Pacaud observed, but he found it exhilarating. During these years he diluted his Rouge ideas with Laurier’s pragmatic liberalism and, under the influence of the small anglophile community of Arthabaskaville, he began to imitate the ways and lifestyle of a British gentleman.

Once the Liberals were in power at both Quebec and Ottawa, they wasted no time in placing their men in the key administrative posts. On 14 June 1878 Henri-Gustave Joly’s government offered Pacaud the positions of protonotary of the Superior Court, clerk of the Circuit Court, and clerk of the crown for the District of Trois-Rivières. Its gesture was a recognition of his competence, his past services, and the need to guarantee the future. There was no reason why he should refuse an offer that, in his view, “was honourable, represented a sort of promotion in my profession, and brought in a handsome income.” In carrying out his duties he demonstrated genuine efficiency and strict political neutrality: no meetings or political discussions were held in the protonotary’s office or the clerk’s office. He had not withdrawn from political life, however. His appointments were the result of a decision by the Liberal leadership to disseminate the party’s ideas and to organize its support in the Trois-Rivières region. The naming of an assistant to Pacaud in May 1879 coincided with the appearance of La Concorde, a newspaper which came out in a weekly and a tri-weekly edition. It displayed a moderate Liberalism and, as implied by its name and its motto, “The country’s interests before party interests,” its aim was to unite moderates of all political stripes around an honest and prudent government, that of Joly. The paper had a particular focus on the development of Trois-Rivières and on the political concerns of Pacaud’s brother-in-law Arthur Turcotte, the speaker of the Legislative Assembly. Pacaud assumed responsibility for La Concorde’s political thrust and seems to have worked at organizing the party. The defeat of the Joly administration in October 1879 brought a reversal in his fortunes. The Conservatives of Trois-Rivières called for his dismissal, and Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*’s government relieved him of his duties as protonotary and clerk on 20 Feb. 1880. By the 25th Pacaud had returned to the practice of law, in partnership with his brother Auguste in Pacaud et Pacaud at 15 Rue des Forges in Trois-Rivières. On 19 April he became editor of La Concorde and he proved to be a fiery polemicist, thoroughly conversant with the mysteries of politics.

By the spring of 1880 the Liberal press, cut off from lavish government contracts both at Quebec and at Ottawa, was in trouble. Le National of Montreal had ceased publication in 1879 and L’Éclaireur of Quebec in March 1880; La Concorde was struggling with financial problems. Only the Montreal papers La Patrie and L’Union survived the débâcle, but their radicalism was damaging to the party. Joly and Laurier raised money from their friends to found a newspaper at Quebec that would counterbalance Joseph-Israël Tarte’s Le Canadien. The first issue of L’Électeur appeared on 15 July 1880. Laurier, Charles-Antoine-Ernest Gagnon, and Charles Langelier and his brother François* helped with the paper, but it lacked an editor who could take on Tarte. Laurier, who wanted to keep control of its content, designated his friend Pacaud. On 18 December Pacaud assumed the editorship and became one of the main organizers of the Liberal party at Quebec. His aim was to bring moderate Conservatives into a coalition with moderate Liberals, and his strategy consisted of undermining the credibility of the Conservative right wing: the clique around Louis-Adélard Senécal* and the ultramontanists associated with the Cercle Catholique de Québec. His candidacy in Bellechasse in the spring of 1882 against Guillaume Amyot*, who soundly defeated him, seems to have been dictated more by circumstances than by desire for a parliamentary career. Pacaud had a talent for polemics and a genius for organization. L’Électeur pursued the ultramontanists: it opposed the Jesuits who wanted a university, and supported division of the diocese of Trois-Rivières (which its bishop, Louis-François Laflèche*, fought against) and the introduction of state control over insane asylums.

Despite his intense activity, Pacaud did not neglect his personal interests. He gradually tightened his grip on Plamondon et Compagnie, a partnership that had been publishing L’Électeur since 1 July 1882. Its principals were Pacaud, Joseph Plamondon, a tanner, Joseph Archer Jr, a lumber merchant, and Amédée-Joseph Auger, an accountant. Pacaud had subscribed one-third of the capital of $1,500. He owned one-third of the equipment, valued at $1,000, and drew a monthly salary of $100. When the agreement expired on 1 July 1883, Pacaud and his friend Charles Langelier became the sole partners. At that time L’Électeur was still a small business; Pacaud served as publisher and, with Ulric Barthe, as editor, Eugène Leclerc* acted as general factotum, and Arthur Marcotte as printer and accountant. Deprived of government contracts, it struggled along and from time to time Pacaud called on the generosity of Laurier, who apparently took steps to stabilize the company. On 1 May 1885 Langelier withdrew from it and was replaced by Barthe, but this arrangement was a pure formality. The two partners would declare in a document notarized on 10 July 1889 that “the name of Monsieur Ulric Barthe appears in the articles of incorporation for the ownership of the aforementioned newspaper only as a gesture of courtesy and for appearance’s sake.” Where had Pacaud found the money to become the sole owner of L’Électeur? From Louis-Adélard Senécal, according to the ultramontanists; from Laurier, according to Liberal rumours. Whatever the case, Pacaud was henceforth the newspaper’s proprietor and had to answer to no one but Laurier.

By 1885 Pacaud was respected as a person, formidable as an opponent, and influential as a power in the Liberal party. His headquarters on Rue de la Montagne (Côte de la Montagne) occupied a single dusty room with a faded screen marking off a secluded area for the two editors and the rest given over to the factotum. Small in stature, always correctly but unpretentiously dressed, ever polite and courteous, Pacaud was full of exuberant friendliness, contagious good humour, and feverish activity. Generous and loyal to a fault, this man who could not remember having missed an election campaign since 1867 had learned over the years to keep private morality separate from political morality. He would use the scaffold in Regina [see Louis Riel*] to propel Honoré Mercier* into power. On 17 Nov. 1885, the day after Riel was hanged, L’Électeur appeared with a black border. Pacaud was a member of the Comité National de Québec and amongst those who wanted to transform the nationalist movement in the province into a political party. He was the organizer and treasurer of a coalition that brought together Liberals, Conservatives, and ultramontanists. By his editorials, which were both rallying calls and war cries, by his carefully framed speeches packed with statistics, by his caustic and fiery wit, and by his ability to size up a situation quickly and take action, he disarmed more than one opponent and played a powerful role in securing the Parti National’s election victory of October 1886.

The formation of Mercier’s government late in January 1887 placed Pacaud at the centre of political power. As publisher of L’Électeur and organizer and treasurer of the Parti National, he became an éminence grise, an effective political power-broker, and the main dispenser of patronage. His first move was to consolidate the government press. On 26 March he founded Belleau et Compagnie to take over publication of L’Électeur and of La Justice, which a group of National Conservatives (Guillaume Amyot, Louis-Philippe Pelletier*, and Jacques-François Belleau) had launched in January 1886. The company had two partners, Belleau and the printer Arthur Marcotte, who in fact was only a front for Pacaud. Plamondon et Compagnie, which continued to own L’Électeur, assumed responsibility for its political thrust. The Compagnie d’Imprimerie Provinciale did the same for La Justice. The establishment of Belleau et Compagnie made economies of scale possible: the separate editorial offices of the two papers were in the same building, which provided a room and services for their common use, as well as a lawyer’s office for Louis-Philippe Pelletier, the president of the Compagnie d’Imprimerie Provinciale. It also facilitated an equitable allocation of government contracts. Well fed at the public trough, L’Électeur diversified and improved its material, with Louis Fréchette, Napoléon Legendre, Arthur Buies, and James MacPherson Le Moine* contributing signed articles. But it remained a newspaper of opinion, concentrating on politics and written for the élite, with a circulation of less than 5,000.

In a new office “literally papered,” according to Rodolphe Lemieux*, “with portraits, emblems, [and] political sketches recalling the great periods of Liberal struggle in Canada,” Pacaud, who was writing less and less, drew with Ulric Barthe the broad outlines of an editorial policy. He had only two ambitions: the victory of his party and the success of his newspaper. His tireless energy was placed at their service. He quickly sensed trends in public opinion, anticipated Mercier’s wishes, and put together schemes that brought results. Along with Charles Langelier at Quebec and Cléophas Beausoleil and Raymond Préfontaine in Montreal, he was the master chef of Mercier’s kitchens, resuming on behalf of the Parti National the political brokerage system of his Conservative predecessors. He appointed office holders, selected candidates in the ridings, awarded contracts and speeded up payment of government accounts, collected kickbacks, paid the premier’s bills, and to please the ultramontanists could use his pen as a holy-water sprinkler. Pacaud’s lifestyle and that of his friends became luxurious. So much power and shady dealing aroused passions. His opponents saw him as an unscrupulous agitator, the second-hand dealer of “official” patronage. In May 1889 Calixte Lebeuf and La Patrie denounced “Pacaud and his gang.” With the approach of the 1890 elections, rumours of scandal multiplied. An affair involving John Patrick Whelan, a contractor who reportedly had obtained contracts through bribes or kickbacks, was said to be only the tip of the iceberg. In April 1890 Lebeuf gave Pacaud a stern rebuke: “It is openly said that this government is the most corrupt ever to sully the panelled walls of the legislative building; that everything there is for sale; that there are no principles, no honesty, no trust, no honour.” Nevertheless, Mercier won the 1890 election with an increased majority. But cracks were beginning to appear: the ultramontamst press, concerned about the rampant corruption, and Pelletier’s La Justice, which objected to state control of asylums, took an independent position on certain questions, particularly on the loan that the premier was going to negotiate in Paris.

While he was away Pacaud settled a number of irritating matters. He cut off government contracts to the ultramontamst papers and had Pelletier ousted from the presidency of the company that published La Justice. He manoeuvred the government into paying damages of $175,000 to Charles Newhouse Armstrong, a contractor who had been excluded from the Baie des Chaleurs Railway Company. This transaction gave rise to rumours that were confirmed by an inquiry launched in August 1890 by the Senate railway coinmittee. Pacaud was believed to have pocketed some $100,000 and distributed it to friends. There was a huge scandal. Mercier repudiated Pacaud. Lieutenant Governor Auguste-Réal Angers* appointed a royal commission of inquiry, which held hearings in October 1891. Pacaud declared that he had used the money to pay election expenses, to underwrite the operations of certain newspapers, including the Waterloo Advertiser and the Quebec Daily Telegraph, and perhaps, inadvertently, to pay off a few personal debts. On 16 December the commission concluded “the transaction between Armstrong and Pacaud . . . was fraudulent, contrary to law and order.” Angers dismissed Mercier as premier and in the election that ensued the Conservatives swept the Liberals from office. Pacaud faced two charges, one in the Superior Court for having masterminded the fraud connected with the Baie des Chaleurs Railway Company, and the other in the Court of Sessions of the Peace for having conspired with Mercier to award a contract to Joseph-Alfred Langlais for supplying stationery in return for a 20 per cent commission on government purchases. He was acquitted by both courts, but thereafter the Liberals made him confine his activities to journalism.

Laurier, now the leader of the party, deplored Pacaud’s mistakes but was unstinting in his help, friendship, and advice. The editorial line he laid down for him can be summed up in three points: maintain a united front within the Liberal party, go easy on the Catholic bishops, and tone down personal attacks. “It is time,” he wrote to Pacaud on 27 Nov. 1894, “for you to turn over a new leaf, and for your newspaper from now on to have its own style, a superior style, beyond and above the vulgarities of our country’s press. No more personal abuse, no more diatribes, no more invective.” However, the hotheaded editor could not always curb his sudden changes of mood. His editorial of 28 Jan. 1896 sharply criticizing Bishop Michel-Thomas Labrecque for requiring Catholics to vote only for candidates who would support the remedial legislation on the Manitoba school system [see Thomas Greenway], deeply upset Laurier. Other articles on the rights of the church with regard to schools, and the serial publication of Le clergé canadien: sa mission, son œuvre, a pamphlet by Laurent-Olivier David that had been condemned by the Congregation of the Index, brought episcopal wrath down on Pacaud’s head. On 27 Dec. 1896 the curés read from the pulpit a collective letter by the bishops of the ecclesiastical province of Quebec that forbade the reading of his newspaper. The Liberal leadership decided to put up a fight. Pacaud changed the paper’s name and the next day, on the same presses and with the same staff, he published Le Soleil. He appealed to the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda and, to cover his tracks, the Compagnie d’Imprimerie de Québec was set up, with Pacaud as the principal shareholder. Bishop Labrecque’s next punitive move was to forbid the reading of Le Soleil. Apostolic delegate Rafael Merry del Val lifted the ban during his stay in Canada in 1897. From then on Pacaud had smooth sailing in Laurier’s wake. He supported the Laurier-Greenway settlement of the Manitoba school question, held forth on the many varieties of imperialism, spoke out against the pitfalls of too much provincial autonomy, attacked the nationalism of Henri Bourassa* and Joseph-Israël Tarte, and argued in favour of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and the Quebec Bridge Company.

But Pacaud was prematurely worn out. In July 1903 he fell seriously ill. Confined to his bed, he dictated articles and sketched out editorials. A stay in Florida did not help him. Back in Quebec, he turned to Laurier to reorganize Le Soleil in the interests of the party and his family. The ill feeling between factions in the party made it difficult to settle the question. Judge Philippe-Auguste Choquette* was hoping to buy the paper and turn it into a pro-Laurier publication, but Simon-Napoléon Parent*, who was then premier of Quebec, opposed the idea. Laurier preferred that Le Soled “be the organ of no one in particular, but that its sole mission be to defend the party.” He imposed his choice. In early December 1903 the Compagnie de Publication “Le Soleil,” made up of Liberals of all shades, including Choquette and Parent, bought the paper for about $112,000.

Ernest Pacaud, who according to Laurier was “not only the heart and soul of this enterprise,” but had “incorporated [it] into his own person,” died reassured about the future of his life’s work. He left behind the memory of a devoted and sincere friend, a loyal party-member, and a courageous fighter.

AC, Québec, État civil, Catholiques, Notre-Dame de Québec, 22 avril 1904; Minutiers, Joseph Allaire, 26 mars 1887; 2 juin 1888; 10 juill., 6 nov. 1889. ANQ-MBF, CE1-48, 26 août 1850, 23 août 1876. ANQ-Q, CN1-328, 11, 13 juill. 1882; T11-1/29, nos.2848 (1882), 3067 (1883), 3084 (1883), 3476 (1885), 4285 (1889); 30, nos.4864 (1892), 5050 (1893); 116, no.1962 (1926); 125, no.31 (1884); 283, no.295 (1894); 303, no.329 (1889); 322, no.463 (1889); 352, no.411 (1894); 378, no.456 (1890); 541, no.734 (1881); 592, no.833 (1891); 614, no.873 (1889); 707, no.1045 (1895); 800, no.1236 (1892); 826, no.1290 (1892); 935, no.1521 (1893); 990, no.1640 (1883). Arch. du Séminaire de Nicolet, Qué., F002 (M.-G. Proulx), 5, no.8; Fichier des étudiants. NA, MG 26, G: 68833–34; MG 29, D36. La Concorde (Trois-Rivières, Qué.), 2 mai 1879; 23, 25 févr., 6, 19 avril, 29 nov., ler déc. 1880. Les Débats (Québec), 31 août 1902. L’Électeur, 1er, 15, 20 déc. 1880; ler janv. 1888; 26 déc. 1896. L’Événement, 14 mars 1902. Le Journal d’Arthabaska (Arthabaska, Qué.), 5 oct., 2 nov. 1877. L’Opinion publique, ler janv. 1880, 3 mars 1893. La Presse, 10 juin 1890, 20 avril 1904. Le Soleil, 28 déc. 1896; 10 mars 1902; 20, 22 avril 1904; 14 avril 1928. Réal Bélanger, Wilfrid Laurier; quand la politique devient passion (Québec et Montréal, 1986). Marguerite Bourgeois, La belle au bois dormant (Trois-Rivières, 1935), 48. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). C.-P. Choquette, Histoire de la ville de Saint-Hyacinthe (Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué., 1930). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), 2: 405. Raoul Dandurand, Les mémoires du sénateur Raoul Dandurand (1861–1942), Marcel Hamelin, édit. (Québec, 1967). Désilets, Hector-Louis Langevin. Directory, Quebec, 1883–1904. J.-A.-I. Douville, Histoire du collège-séminaire de Nicolet, 1803–1903 . . . (2v., Montréal, 1903). P. A. Dutil, “The politics of Liberal progressivism in Quebec: Godfroy Langlois and the Liberal Party, 1889–1914” (phd thesis, York Univ., North York [Toronto], 1987). J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise, vols.2–3. Philippe Landry, Cette enquête: lettres de M. Ph. Landry, député à la Chambre des communes du Canada à M. E. Pacaud, rédacteur de “L’Électeicr” (Québec, 1883). Marc La Terreur, “Armand Lavergne; son entrée dans la vie publique,” RHAF, 17 (1963–64): 42–45. J. A. Macdonald, Troublous times in Canada; a history of the Fenian raids of 1866 and 1870 (Toronto, 1910). Mandements, lettres pastorales et circulaires des évêques de Québec (19 vol. parus, Québec, 1887– ), [8]. Quebec Official Gazette, 1878–80. Ernest Pacaud, Lettre de monsieur Ernest Pacaud, protonotaire, à l’hon. L.-O. Loranger, procureur général, 16 février 1880 (Trois-Rivières, 1880). Lucien Pacaud, Sir Wilfrid Laurier; lettres à coon père et a ma mère, 1867–1919 (Québec, [1935]). Joseph Pope, Public servant: the memoirs of Sir Joseph Pope, ed. Maurice Pope (Toronto, 1960). Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.1–11. Henri Vallée, Les journaux trifluviens de 1817 à 1933 (Trois-Rivières, 1933), 43–45. [J. S. C.] Würtele, Adresse de l’hon. juge Würtele aux petits jurés dans la cause de la reine vs l’honorable Honoré Mercier et M. Ernest Pacaud, 4 novembre 1892 ([Montréal?], 1892).

Cite This Article

Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin, “PACAUD, ERNEST (baptized Philippe-Olivier),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pacaud_ernest_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pacaud_ernest_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | PACAUD, ERNEST (baptized Philippe-Olivier) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |