Source: Link

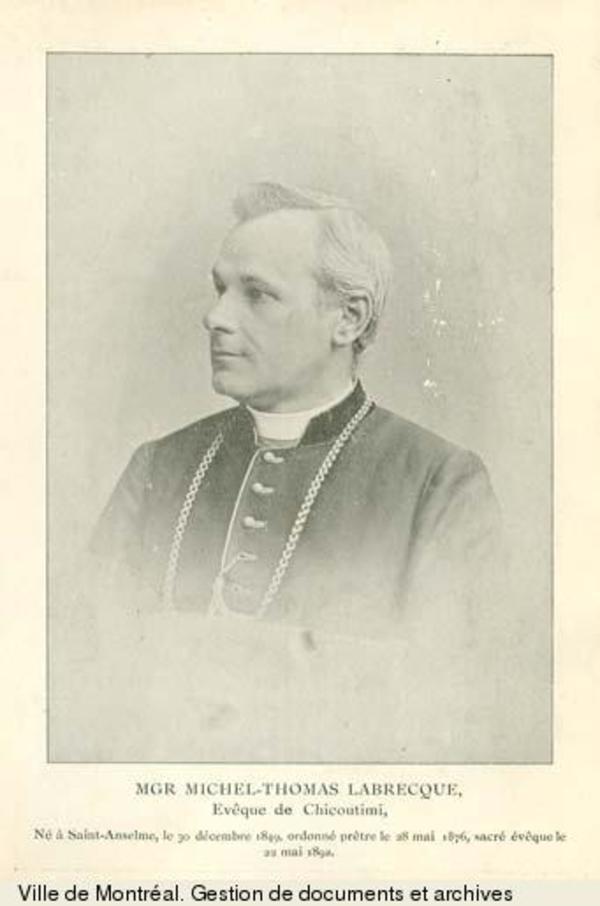

Labrecque, MICHEL-THOMAS (baptized Labreque), Roman Catholic priest, teacher, and bishop, b. 30 Dec. 1849 at Saint-Anselme, Lower Canada, son of François Labrecque (Labreque), a farmer, and Emélie Lemelin; d. 3 June 1932 in Chicoutimi (Saguenay), Que.

The fourth child in a family that would number 13 children, Michel-Thomas Labrecque attended elementary school at the Collège de Lévis (1858–63) and pursued his classical studies at the Petit Séminaire de Québec (1864–72). His teachers remarked not only on his talents in writing and oratory, but also on “his love of work, his diligence, his good judgement and his outstanding intelligence.” L’Électeur of Quebec would echo these sentiments on 25 April 1892.

Having aspired to the priesthood from a very young age, Labrecque entered the Grand Séminaire de Québec in 1872, where Abbé Louis-Nazaire Bégin* was one of the teachers who inspired him. While pursuing theological studies, which led to his ordination on 28 May 1876, he taught second-form pupils (1872–73) and rhetoric students (1873–80) at the Petit Séminaire de Québec. After earning an ma from the Université Laval in Quebec City on 23 June 1880, he travelled that same year to the French Seminary in Rome to further his training. He received a doctorate in canon law from the Roman Seminary on 26 June 1882 and a doctorate in theology from St Thomas College on 13 May 1883.

Abbé Labrecque took advantage of his sojourn to gain an understanding of the intrigues and deep division in the Canadian episcopate, and also to familiarize himself with the functioning of the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda. In his spare time he visited museums and witnessed the splendour of papal celebrations. He went to the sanctuary of Our Lady of Good Counsel in Genazzano to worship before the image of the Virgin Mary, for whom he felt a special devotion. He also followed the meetings of the Pontifical Academy of St Thomas Aquinas when Thomist philosophy once again spread throughout the seminaries. He was passionately interested in lectures by the great names among Roman teachers, including Father Matteo Liberatore, one of the authors of Pope Leo XIII’s future encyclical Rerum novarum. The rampant anti-clericalism in Europe also attracted his attention. Throughout his life Labrecque suffered from an immense and obsessive fear of freemasonry and liberalism, which promoted secular public schools and the separation of church and state. He expressed this dread in 1896 while defending the rights of denominational schools for Roman Catholics in Manitoba [see The Electoral Campaign of 1896 and the Manitoba School Crisis]. He expressed it again in 1917 and 1918 when he attacked the Conservative government of Sir Robert Laird Borden for calling up clerks (tonsured seminarians or those in the process of becoming so) for compulsory military service. So strong was his opposition to their conscription that he went so far as to advocate the separation of the province of Quebec from Canadian confederation.

During his return journey Labrecque visited Paris, Marseilles, and Lourdes, before stopping to see two of his brothers in the United States. He arrived in Quebec City in 1883, equipped with the latest useful publications for teaching and immediately became professor of moral theology at the faculty of theology of the Université Laval. In 1887 he joined the council of the Séminaire de Québec and that same year took up the post of director of seminarians at the Grand Séminaire de Québec. He was also a founding director of the Œuvre des Clercs, chaplain to the Académie Commerciale de Québec, and, from at least 1889 to 1892, assessor of the metropolitan tribunal. He thereby proved himself a man of action, able to manage several tasks at once.

Just as Labrecque was considering the pursuit of a career devoted to study, teaching, and prayer, the question arose of a successor to the cardinal and bishop of Quebec, Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau*, because of his health. On 18 Dec. 1891 Bégin was named titular archbishop of Cyrene and the cardinal’s coadjutor, leaving his Chicoutimi seat vacant. In both the Séminaire de Québec and the Vatican, rumours circulated concerning his replacement. On the recommendation of the Canadian episcopate, three names were advanced at the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda: Joseph-Clovis-Kemner Laflamme*, dean of the faculty of arts of the Université Laval in Quebec; Olivier-Elzéar Mathieu*, principal of the Séminaire de Québec; and Labrecque. Following Laflamme’s refusal of the post, Labrecque – who was considered an ultramontane by his defenders, bishops Louis-François Laflèche* and André-Albert Blais of the dioceses of Trois-Rivières and Rimouski respectively – became bishop of Chicoutimi on 8 April 1892.

On 22 May, in the basilica of Notre-Dame in Quebec City, Cardinal Taschereau presided over the consecration of the new prelate “with all the pomp and solemnity established by the Roman Church,” as L’Électeur reported the next day. Following a reception at the Séminaire de Québec and then at Saint-Anselme, Labrecque was welcomed at the Chicoutimi wharf on 28 May. The installation ceremony, including the prescribed speeches, took place in the recently completed cathedral of Saint-François-Xavier, in the presence of bishop Bégin and Abbé Benjamin Pâquet*, rector of the Université Laval and superior of the Séminaire de Québec.

In his prime, at age 42, Labrecque began his life as a bishop and prince of the Catholic Church. In his opening decree, he unveiled his concept of his role as pastor. Referencing St Thomas Aquinas, he stated that a bishop was automatically “the lieutenant of Jesus Christ,” “the servant of souls,” and “the dispenser of truth.” His motto, taken from the Second Epistle to the Corinthians, chapter 12, verse 15, set forth his plan of action: Impendam superimpendar (I will very gladly spend and be spent for you).

The newly consecrated bishop made the customary visit to the Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Vallier, run by the Augustines de la Miséricorde de Jésus (Augustinian nuns), whom he would help to acquire the Hôpital de la Marine through his representations to the federal government between 1893 and 1895. Labrecque then moved on to the Séminaire de Chicoutimi, where waiting students and faculty paid tribute to him. On 12 and 13 June his tour continued towards Lac Saint-Jean. He stopped at Saint-Louis-de-Métabetchouan (Chambord), staying with his former fellow disciple at the Grand Séminaire de Québec, the curé François-Xavier Belley, and at the Ursuline monastery in Roberval [see Malvina Gagné*]. He informed Bégin on 15 June that he was “delighted with the priests and the people of [his] diocese,” despite “childish behaviour” by certain members of his clergy when he arrived. Subsequently, in May 1893 he undertook the first of ten pastoral rounds of his episcopate, each requiring two months of his time. These rounds allowed him to take the measure of a diocese that was flourishing as a result of settlement and industrialization in the pulp and paper and aluminum sectors. Created in 1878, the diocese already numbered 39 parishes, 64 priests, and nearly 55,000 souls; the number of faithful would reach 125,000 by the time he resigned in 1927. During this first tour the bishop ascertained that there were insufficient numbers of priests, missionaries, and teachers. He also became aware of the vastness of the territory to be covered: as well as the regions of Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean and Charlevoix, the diocese included, as of 30 May 1892, the apostolic prefecture of the Gulf of St Lawrence (it would, however, be entrusted to the Eudists [Congregation of Jesus and Mary] in 1903), where Anticosti Island was situated. In addition to these rounds, he made three ad limina visits to Rome – in 1896, 1903, and 1914. During his second trip he supported, in the presence of Pope Pius X, the cause of Bégin’s promotion to cardinal.

During his episcopate Labrecque established 34 parishes and ordained 175 priests. He founded three orphanages, two normal schools, and two congregations: the Sœurs de Notre-Dame du Bon Conseil de Chicoutimi in 1894, to address the educational needs of the diocese [see Françoise Simard], and the Sœurs de Saint-Antoine de Padoue in 1904, for domestic service at the Séminaire de Chicoutimi [see Elzéar De Lamarre*].

Labrecque also welcomed religious communities to give structure to his diocese. Among them were the Little Franciscans of Mary in the parish of Saint-Pierre et Saint-Paul [see Marie Bibeau*], the Trappists, who served the ecclesiastical district of Saint-Michel-de-Mistassini (Dolbeau-Mistassini) (1892) [see Pierre Oger*], the Marist Brothers in Roberval and Chicoutimi (1897 and 1901), the Sisters of Charity of St Louis in Saint-Irénée (1908) [see Sir Rodolphe Forget*], the Capucins at the Ermitage San’Tonio at Lac Bouchette (1925) [see Elzéar De Lamarre], the Jesuits in Chicoutimi (1925), and the Brothers of the Christian Schools in Port-Alfred (Saguenay) (1926). In 1903 he met with French communities in exile: the Brothers of Saint Francis Regis in Saint-Amédée (Péribonka), the Eudists in the parish of Sacré-Cœur-de-Jésus [see Gustave Blanche*], where he had worked from 1893 to 1903 as an officiating priest and confessor in the chapel he had built in 1892, and the Servants of the Blessed Sacrament in Chicoutimi, founders of a eucharistic cenacle. To complete the canonical organization of his diocese, he would establish the chapter of the Chicoutimi cathedral in 1926.

In Chicoutimi, as in any diocese, spiritual and temporal affairs intermingled; they provided an opportunity to gauge Labrecque’s temperament and convictions. Certain personality traits – such as irascibility, impulsiveness, and authoritarianism – revealed themselves to be quite the opposite of those of St François de Sales, whom Labrecque looked to as his guide. Labrecque’s decrees and correspondence attest to this: in 1896, for example, he prohibited the faithful from attending meetings of candidates who were in favour of the Laurier–Greenway compromise on Manitoba schools [see Thomas Greenway*; The Laurier–Greenway Agreement (1896)]. At the end of December Labrecque censored the local press and ordered his clergy to refuse absolution to readers of La Patrie and Le Cultivateur, Montreal newspapers that supported Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier* [see Ernest Pacaud*]. As he had stated on 6 March 1896 in a letter to Bégin, he considered Laurier a “traitor to his religion and his nationality” because of his conduct in Ottawa and his refusal to acknowledge that the church took precedence over the state in school issues. In Labrecque’s view it was ill-advised to renounce the right to separate schools, which was enshrined in the constitution of 1867, as the same situation could arise sooner or later in the rest of the dominion. Furthermore, he felt the church had to stand firm on not making any concessions at all.

Labrecque’s temperament was also revealed on 8 March 1900, when the bishop ordered the seminary’s superior, Abbé De Lamarre, to put an end to the era of deficits. The growth of the seminary suffered from the decision, despite the imposition six years earlier of a 2 per cent tax over 20 years, taken from the income of the secular clergy to repay the mortgage Bégin had authorized to expand the institution. For Labrecque, thriftiness was a virtue acquired through his education, and which he exercised in the extreme, to the point of the bare necessities only. Self-denial permeated his management style and was to engender a climate of fear and suspicion that would undermine his episcopate.

The bishop’s authoritarian tone was also apparent in 1902 when he spoke out against the immigration of a group of Lutheran Finns to the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region. His intervention contributed to the failure of a project by brothers Knut and Oscar William Nordin to build a sawmill and a bark mill, a plan supported by the press and local leaders. In a letter written in April 1902 to one of the project’s supporters, the Conservative mp for Chicoutimi-Saguenay, Joseph Girard, the bishop stated his regret about the politician’s stand. He implored him to change his mind and pointed out that the plan was “a national and religious danger” for a largely Catholic, francophone area. Furthermore, he doubted the benefits of establishing the venture. He advanced as evidence the experience of some one hundred Finnish immigrants sent the previous month into the future townships of Ferland and Boilleau: the Nordins had not honoured their commitment to settle them in small groups, make them learn French, and convert them to Catholicism before they eventually married Canadian women. He believed that after exploiting the forest, the Finns would rapidly leave the region, “saddling us with imported people in large numbers who will be an obstacle to the functioning of the parishes and the ruin of our homogeneity, which is a source of so many temporal and spiritual benefits.”

Labrecque’s followers were also subjected to his impulsiveness. This led to several arguments and disputes, which sometimes turned to his disadvantage. The most sensational incident concerned a case of verbal abuse, brought against him by the lawyer Louis de Gonzague Belley – counsel for Price Brothers and Company Limited as well as mayor of Chicoutimi (1907–8) – in the Superior Court of Chicoutimi on 21 Feb. 1908. It followed testimony given by the bishop at court during a libel case that pitted Belley against his political enemies during the municipal election of 1907. While the priests of the seminary attempted to keep the case out of the local newspapers, the affair caused a big stir in the Quebec City and Montreal press. The religious and civil authorities in Quebec were afraid that the Protestant press would use the trial to belittle the Canadian episcopate and clergy. On 29 February judge Honoré-Cyrias Pelletier stressed in a letter to Bégin that he was doing all he could to pacify the parties. Labrecque had to try not to lose his temper, and Belley had to remember “that a Catholic was not allowed to mistreat his bishop, whatever the latter’s behaviour.” Upset by this case, Labrecque took refuge in his bishop’s palace. On 1 April, he proposed an out-of-court settlement: he agreed to pay the sum of $400 in damages and retract his comments by writing a letter dictated by Belley. Published in Chicoutimi’s Le Travailleur on 9 April 1908, the letter confirmed the good reputation of the lawyer with regard to his family, clients, and fellow citizens.

The rebuilding of the cathedral in Chicoutimi, which had been destroyed in 1912 during the great fire that ravaged the entire eastern district of the city, illustrates once again Labrecque’s blunt, stubborn character. He categorically rejected the plan of Abbé Eugène Lapointe* and Abbé Jean Bergeron, vicar general and procurator of the seminary respectively, to rebuild the cathedral on the site of the seminary, which had also been consumed by fire. So it was that the new seminary, inaugurated in 1914, was erected on higher ground, signalling urban renewal and architectural modernity in Chicoutimi. To cut costs, the cathedral, which was consecrated in 1916, was constructed above the ruins. Despite the recommendation of the architect, René-Pamphile Lemay, it was not rebuilt to be fireproof, and it burned down again in January 1919. To remedy the situation, a concrete structure would appear, but not until 1922.

On another matter Labrecque was among the first bishops in the province of Quebec to take an interest in social projects called for by Pope Leo XIII. In 1904, therefore, he had inaugurated a series of lectures for workers, which were organized by the Chicoutimi Pulp Company [see Joseph-Dominique Guay*]. Also that year he obtained for the company’s general manager, Julien-Édouard-Alfred Dubuc*, the title of knight of the Order of St Gregory the Great. With the help of Eugène Lapointe, from 1905 he fought a hard battle against international unions and Sunday labour. He authorized the reorganization of the Fédération Ouvrière de Chicoutimi (founded in 1907) to enable, in 1912, the creation of the first Catholic trade union in North America: the Fédération Ouvrière Mutuelle du Nord. A defender and promoter of French Canadian nationalism, he was chaplain to the conscripts incarcerated in the Chicoutimi district jail for their refusal to take part in the First World War.

Labrecque suffered serious health problems from 1919 onward. In 1924 he appointed Abbé Léon Maurice second vicar general to help him with administration. In 1927 he resigned after 35 years in the episcopate, having been designated by Rome the titular bishop of Helenopolis in Bythinia. Charles-Antonelli Lamarche succeeded him in 1928. Labrecque withdrew to the Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Vallier of Chicoutimi on 2 Jan. 1928, suffering from nervous depression and experiencing misgivings about some of his ordinations. After a long illness he died there on 3 June 1932, the day of the procession of the feast of the Sacred Heart, which he had established in the diocese in 1918. In keeping with his spiritual testament, his body was buried on 8 June in the crypt of his cathedral and his heart in the chapel of the Servants of the Blessed Sacrament.

During the celebration of the silver anniversary of his episcopate in 1917, Labrecque had been given, at the instigation of Abbé Lapointe, the honorary title of assistant to the pontifical throne. As was reported in the Le Progrès du Saguenay of Chicoutimi on 24 May, the bishop gloried in having maintained and strengthened “the Church of Chicoutimi in the sentiments of an unshakeable submission to the Holy See and its doctrines, where [his] predecessors had established it so firmly.… The Pope, the papal doctrine, and the papal directions, he asserted, these have been my primary concern in governing this diocese.” Considered by clerical biographer Mgr André Simard to be one of the outstanding figures of the Canadian episcopate, Michel-Thomas Labrecque exemplifies, through his life story, accomplishments, and writings, the spirit and the institution of a triumphant Roman Catholic Church in a world where secularization had not yet accomplished its work.

Mgr Michel-Thomas Labrecque is the author of, among other works, Sermon pour la fête de saint Jean-Baptiste: prononcé à la basilique de N.-D. de Québec le 25 juin 1888 (Québec, 1888) and Catéchisme de la perfection religieuse: commentaire de la règle des Sœurs du Bon-Conseil fait suivant la doctrine de S. François de Sales (Chicoutimi [Saguenay], Québec, 1903). Many of his writings can be found in Mandements, lettres pastorales et circulaires des évêques de Chicoutimi (26v., Chicoutimi, 1878–79), 3–8.

Arch. de l’Archidiocèse de Québec, 31 CR (diocèse de Chicoutimi, vol. I–II); I: 86 (lettre de l’abbé Eugène Lapointe à Son Éminence le cardinal Bégin, 12 mars 1917); I: 95 (lettre de S. E. le cardinal Ledochowski, préfet de la S. C. de la propagande à Rome, à Mgr Michel-Thomas Labrecque, du 26 juin 1897); II: 26 (lettre du juge Honoré Cyriac à S. G. Mgr L. N. Bégin, 29 févr. 1918); II: 86a (lettre de l’abbé Eugène Lapointe à Son Éminence le cardinal Bégin, 27 mars 1917); II: 177 (lettre de Mgr Michel-Thomas Labrecque au Très Saint-Père, 29 août 1927); 210 A (reg. des lettres, vol.36–42). Arch. de la Soc. Hist. du Saguenay (Saguenay), P002 (coll. de la Soc. Hist. du Saguenay), S1, D275 (Labrecque, Michel-Thomas (Mgr)–Affaire Belley); S2, P813 (mémoires de Mgr Eugène Lapointe). Arch. de l’Évêché de Chicoutimi (Saguenay), P53 (fonds Mgr Michel-Thomas Labrecque); Reg. des lettres des évêques de l’évêché de Chicoutimi, sér.A., vol. I (1878–96), vol. II (1896–1912), vol. III (1912–63). BANQ-Q, CE306-S3, 1er janv. 1850. BANQ-SLSJ, CE201-S2, 8 juin 1932; TP11, S14, SS2, SSS7, 21 févr. 1908. Centre Hist. des Sœurs de Notre-Dame du Bon-Conseil (Saguenay), P001 (fonds Mgr Michel-Thomas Labrecque). MCQ-FSQ, SME13/MS34-4; MS34-5. Gérard Bouchard, “Les Saguenayens et les immigrants au début du 20e siècle: légitime défense ou xénophobie?,” Canadian Ethnic Studies (Calgary), 21 (1989), no.3: 20–36. Antonio Dragon, L’Abbé Delamarre, fondateur des Sœurs antoniennes de Marie et des pèlerinages du lac Bouchette ([Chicoutimi], 1974). F. X. E. Frenette, Monseigneur Michel-Thomas Labrecque, troisième évêque de Chicoutimi (1892–1932) (Chicoutimi, 1954); Notices biographiques et notes historiques sur le diocèse de Chicoutimi (Chicoutimi, 1945). Gaston Gagnon, Au royaume du Saguenay et du Lac-Saint-Jean: une histoire à part entière, des origines à nos jours (Québec, 2013); “Genèse d’un livre: Les évêques et les prêtres séculiers au diocèse de Chicoutimi, 1878–1968,” Saguenayensia (Chicoutimi), 20 (1978): 81–85. P[olyeucte] Guissard, Histoire de la congrégation des Sœurs antoniennes de Marie, reine du clergé, 1904–1958 (Chicoutimi, [1960]). Histoire de l’Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Vallier de Chicoutimi, 1884–1934 (Chicoutimi, 1934). Histoire du catholicisme québécois, sous la dir. de Nive Voisine (2 tomes en 4v. parus, Montréal, 1984– ), tome 2, v.2 (Philippe Sylvain et Nive Voisine, Les XVIIIe et XIXe siècles: réveil et consolidation (1840–1898), 1991); tome 3, v.1 (Jean Hamelin et Nicole Gagnon, Le XXe siècle (1898–1940), 1984). V. A. Huard, Labrador et Anticosti: journal de voyage, histoire, topographie, pêcheurs canadiens et acadiens, Indiens montagnais (Montréal, 1897). Les Labrecque en Amérique: 1657–2007, sous la dir. de Gaston Labrecque et al. (Saint-Raphaël-de-Bellechasse [Saint-Raphaël, Qué., 2008]). Jean LeBlanc, Dictionnaire biographique des évêques catholiques du Canada … (2e éd., Montréal, 2012). Marius Paré, L’église au diocèse de Chicoutimi (4v., Chicoutimi, 1983–2000), 2–4. Normand Perron, Un siècle de vie hospitalière au Québec: les Augustines et l’Hôtel-Dieu de Chicoutimi, 1884–1984 (Sillery [Québec] et Chicoutimi, 1984). Denise Robillard, La traversée du Saguenay: cent ans d’éducation: les Sœurs de Notre-Dame du Bon-Conseil de Chicoutimi, 1894–1994 ([Saint-Laurent [Montréal]], 1994). Jacques Rouillard, Les syndicats nationaux au Québec, de 1900 à 1930 (Québec, 1979). André Simard, Les évêques et les prêtres séculiers au diocèse de Chicoutimi, 1878–1968: notices biographiques (Chicoutimi, 1969), 32–36. O. D. Simard, “Monseigneur Michel-Thomas Labrecque, troisième évêque de Chicoutimi, 1892–1927,” dans Évocations et témoignages: centenaire du diocèse de Chicoutimi, 1878–1978 (Chicoutimi, 1978), 257–64. Robert Simard, Le séminaire de Chicoutimi: sa participation au monde de l’éducation et de la culture dans les régions du Saguenay Lac St-Jean et de Charlevoix, 1873–2007 (Chicoutimi, [2013]). J. C. Tremblay, Les noces d’argent épiscopales de S. G. Monseigneur M. T. Labrecque (Chicoutimi, 1917). Univ. Laval, Annuaire, 1865–93.

Cite This Article

Gaston Gagnon, “LABRECQUE, MICHEL-THOMAS (baptized Labreque),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/labrecque_michel_thomas_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/labrecque_michel_thomas_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gaston Gagnon |

| Title of Article: | LABRECQUE, MICHEL-THOMAS (baptized Labreque) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 14, 2025 |