Source: Link

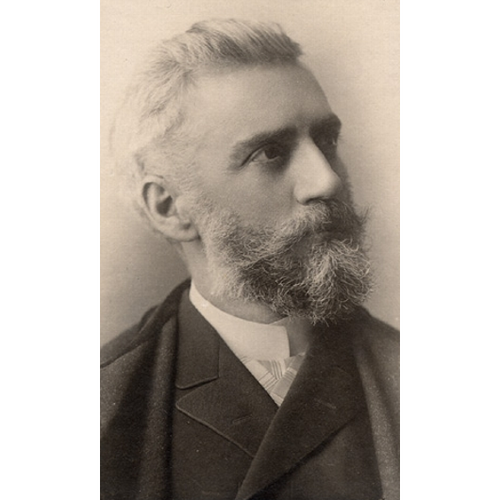

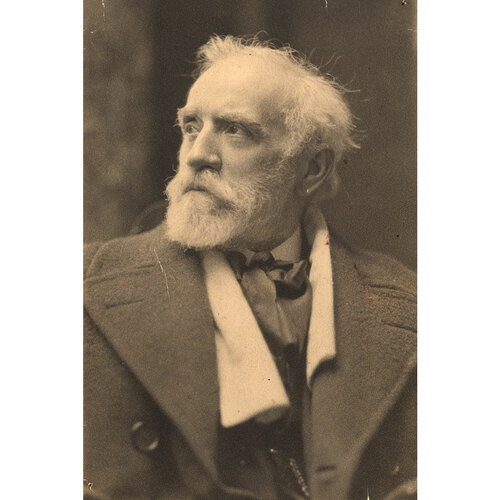

HUOT, CHARLES (baptized Charles-Édouard-Masson), painter, drawing teacher, and illustrator; b. 6 April 1855 at Quebec, son of Charles Huot, a merchant, and Aurélie Drolet; m. September 1885 Louise Schlachter in Belitz (Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania), Germany, and they had a daughter; d. 27 Jan. 1930 in Sillery, Que.

Hormisdas Magnan*, the painter’s friend and first biographer, would note in 1932 that Charles Huot was said to have demonstrated talent for drawing very early on, copying landscapes from a book his father had given him. Charles entered the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière as a boarder in January 1866 at the age of ten; he would leave in July 1870, having completed his first year of commercial studies. His mother died on 26 September as he was entering the École Normale Laval in Quebec City. Few traces remain of the four years he spent in this institution, but various facts suggest that Huot was becoming increasingly interested in painting. First, the sale of a “very beautiful painting of animals done by M. Huot” at the auction of Cornelius Krieghoff*’s estate – which was reported in Le Journal de Québec on 19 May 1877 – implies that the aspiring painter and the master had met. Huot may have used the occasion of Krieghoff’s final stay at Quebec (between 1870 and 1872) to take lessons, but there is no way to confirm this hypothesis. As well, Magnan revealed that the presentation of the Joseph-Légaré collection at the Université Laval in 1872 so fascinated Huot that he returned several times to examine some of the paintings. Huot learned and became a skilful painter, as his works from 1873 prove. He received his first official commission from Clément Vincelette, the superintendent of the Asile de Beauport, who wanted a painting of the institution and its outbuildings. The work, dated 2 Dec. 1873, was displayed in the window of a music shop owned by Robert Morgan on Rue de la Fabrique in Quebec City. From then on, the artist received encouragement. In June 1874 La Minerve would note that Antoine Plamondon*, “who, ordinarily, is quite harsh in his assessments, warmly praised this painting and fully acknowledged the artist’s talent.”

The success Huot achieved soon earned him the support of Abbé Pierre Lagacé, principal of the École Normale Laval, who set up a subscription committee chaired by architect Eugène-Étienne Taché* to send him to study in Europe. On 30 May 1874 Le Journal de Québec announced that $1,400 had been collected “to cover [the] travel costs and the expenses that a four-year stay in Paris will require.” Huot left Quebec on 6 June, at the age of 19, to enter the studio of academic painter Alexandre Cabanel; he lived with the family of Gustave Lefèvre, principal of the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse Niedermeyer. On 16 March 1875 he was finally admitted to the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, where he would do the classical academic program. An unpleasant surprise awaited him the following year, however: the subscribers withdrew their assistance, despite Abbé Lagacé’s repeated requests. Huot thus had to pursue his studies while supporting himself, though Lefèvre did cover his room and board.

In 1876, participating in the Paris Salon for the first time, Huot received an honourable mention and four of his works were accepted for the annual exhibition of the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts. He thus prepared actively for the 1877 Salon, where he presented a skilfully executed oil on canvas, Le bon Samaritain (now held at the Musée Tavet-Delacourt, in Pontoise, France), which showed both his academic training and his progress. After finishing his studies at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, probably in 1879, he took part in the salons of 1881, 1882, 1884, and 1885. During these years Huot worked on various projects. In La Presse on 20 Jan. 1927, he would note: “I came first in the competition in which the prize was a commission . . . to reproduce a masterly work by Paul Beaudry [Baudry], ‘Les Muses,’ imitative of tapestry, which one can admire in the foyer of the Opéra. This project took me two years. Then I did illustrations for Charles Delagrave, Firmin Didot, Hachette.” In 1881 he lived for a few months in a former residence of the Marquise de Sévigné, where he produced paintings of a decorative type for a Paris exhibition. An ageing Huot would take pleasure in telling certain anecdotes related to this sojourn, which Maurice Hébert would evoke in a poem entitled “Le soulier de satin; conte au coin du feu,” published in Le Canada français (Québec) in May 1925.

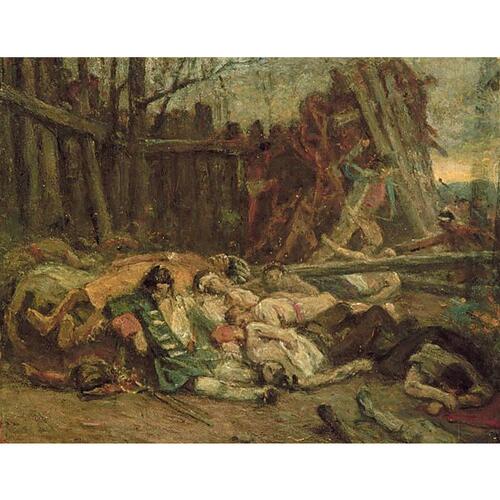

Huot married a pastor’s daughter, Louise Schlachter, in Belitz in September 1885. The following year, the chance to return home materialized when the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who were thinking of entrusting him with the task of decorating the church of Saint-Sauveur, had him come to Quebec City. Huot arrived on 18 July, with the lustre of his studies in Paris and of 12 years spent in Europe. He hurried to exhibit a few works in Montreal, on Rue Notre-Dame, namely genre scenes – his favourite subjects – and a religious painting in the style of Eustache Le Sueur. Also on display was a drawing that had won him a silver medal in the spring at the second Blanc et Noir exhibition in Paris. While establishing new relationships, Huot tended his old ones by publicly thanking his patrons in L’Étendard (Montréal). In January 1887 the Oblates officially commissioned 13 paintings. A few days later Huot left to rejoin his wife in Paris, intending to undertake his first large-scale project there. Instead, however, he moved in with his father-in-law in Neukrug (Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania), where his wife gave birth to their daughter. He had the use of a large studio for the painting of the five canvases that would decorate the vault of the church of Saint-Sauveur. The work progressed and by January 1888 Quebec’s Le Courrier du Canada reported on the success enjoyed by Huot, who exhibited each work in Germany upon finishing it. The following October the paper mentioned that in the three days the painting La fin du monde was on view, “more than 3,000 people went to admire this masterpiece.” The flattering remarks in the Rostock and Schwerin newspapers, which were quoted regularly in Quebec publications, created a favourable climate for Huot, who landed at Quebec with his wife and daughter on 28 Oct. 1889, with his five finished canvases. Unquestionably, the Saint-Sauveur undertaking launched the painter’s career; he could count increasingly on influential connections. His fame spread through an article by Ernest Gagnon* in the Revue canadienne (Montréal), and then pieces in L’Électeur (Québec) by Louis Fréchette* (who, by 1890, suggested Huot for the job of decorating the provincial legislative building). The decor of the church of Saint-Sauveur was appreciated by Huot’s contemporaries, who regarded him as a true artist. The present condition of the paintings and the loss of a portion of them make it difficult to evaluate the work, but they still give the impression of derivative academicism. Although the work has been criticized for its lack of unity, its monumental decor nonetheless constitutes an important example of the aesthetics flourishing at the turn of the 20th century.

Back at home, Huot set about building up a clientele. He first had to finish the eight other paintings commissioned for the church of Saint-Sauveur, which would be completed in May 1893. By the summer of 1890 he was doing portraits; in the autumn he opened a painting school in his home, located at the corner of Avenue de Salaberry and Rue Grande Allée. At about the same time, he was commissioned to do 18 paintings for the church of Saint-Joseph parish in Carleton, whose interior decor was finished in November 1892. In the years that followed, the parishes of Saint-Jean-Baptiste and Notre-Dame in Quebec City, the parish of La Nativité-de-Notre-Dame at Beauport, as well as the Sœurs de la Charité de Québec would purchase works from him. The painter also accepted certain projects that ensured him good visibility, for example, the creation of an Apothéose de la charrue for the festival of the Order of Agricultural Merit in 1890, and the photo-engraved reproduction of a drawing of the carnival of Quebec in 1894. Thousands of the latter would sell in Canada and 30,000 copies of it would be printed in New York. In 1894 Huot participated for the first time in the exhibition of the Art Association of Montreal, and he would be present again in 1908 and 1909. From 1895 he also taught freehand drawing at the École des Arts et Métiers at Quebec.

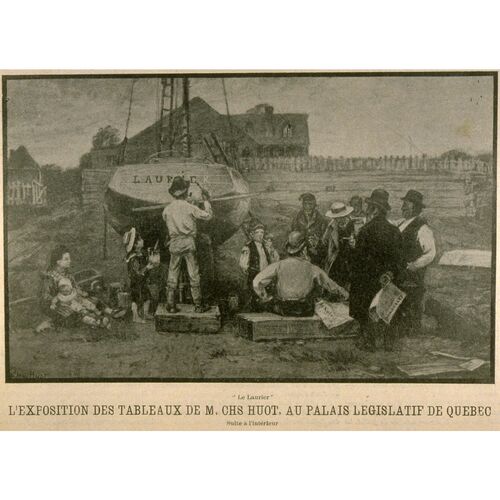

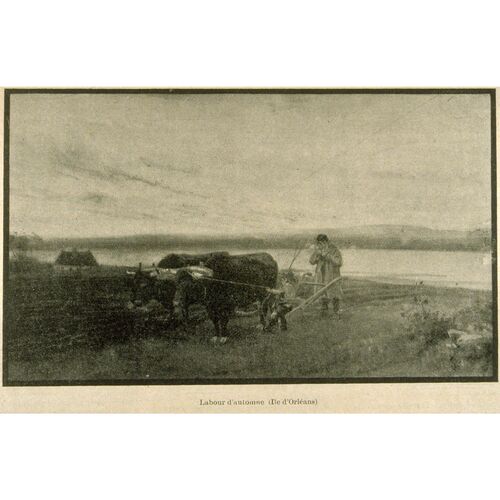

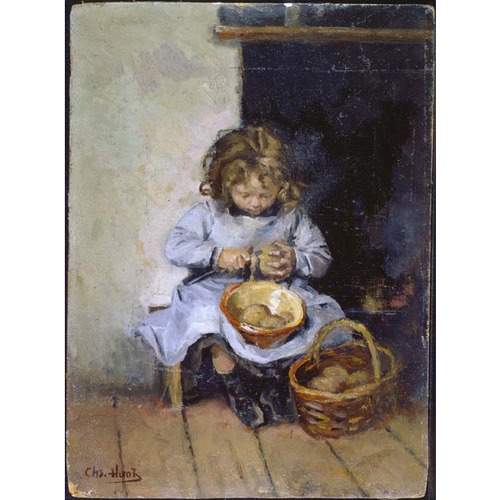

From 10 to 21 May 1900 Huot had a solo exhibition of some one hundred pieces at the legislative building, where, at least in 1898, he had his studio. The event earned him rave reviews, such as the one in Le Courrier du Canada on 22 May, highlighting the nationalist character of the works: “The first thing that strikes the visitor . . . is . . . the national, almost patriotic character of the works. . . . The perfume of Canadianism that they give off is exquisite.” The landscapes and genre scenes inspired by the inhabitants of the Île d’Orléans, where Huot had spent his last few summers, were well received by people supporting clerical-nationalism. At the time, attachment to religion and to tradition dominated the discourse of French Canadians, who recognized themselves in and projected themselves into some of the subjects treated by the painter. These works should, in fact, be compared with the paintings of Horatio Walker* and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté* that celebrate the traditional way of life. When Pierre-Georges Roy* published his book L’île d’Orléans in 1928 in Quebec City, he would recall this aspect of Huot’s career by reproducing a few of the pieces shown in the 1900 exhibition. Also, the texts of Henri Beaudé, known as Henri d’Arles, would help publicize the painting Le sanctus à la maison (destroyed in the fire of February 1966 at Spencer Wood in Sillery, the official residence of the lieutenant governor of the province of Quebec); it would become extremely popular and inspire a poem by Pamphile Le May* (in Les gouttelettes: sonnets, an anthology published in Montreal in 1904). Towards the end of his life, in 1925, Huot was to recognize the importance of this work: in that year he presented it at the salon of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, even though he had participated in their exhibitions in 1902, 1903, and 1908.

From 1900 Huot regularly undertook contracts in the Saguenay region. He owed them largely to his cousin and friend Abbé Elzéar De Lamarre, who was then the chaplain of the Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Vallier in Chicoutimi. In the autumn he did a painting for its chapel. Then he created in wax a recumbent statue of St Anthony of Padua in the throes of death, a model sculptor Louis Jobin would render in wood. In 1901 he painted a Résurrection for the church of Saint-Patrice-de-la-Rivière-du-Loup parish in Rivière-du-Loup, to which, in 1903, he delivered stations of the cross that he had exhibited initially with the Ursulines of Quebec. One commission followed another: they came from the cathedral of Saint-François-Xavier in Chicoutimi, St Patrick’s Church at Quebec, and the parish of Saint-Jérôme (Métabetchouan) in the Lac-Saint-Jean region. In addition, in 1903 La Nouvelle-France (Québec) printed a talk he gave upon the death of painter James Tissot, and Beaudé published a work in New York entitled Propos d’art that was devoted to Huot.

Huot returned to Europe with his family in November 1903 and, after a brief stay in Germany, he went to Italy; in Rome he took classes with Francesco Gai at the Accademia di San Luca. He came back to Quebec City alone in June 1904. Immediately upon his return, the parish of Saint-Ambroise in Loretteville commissioned him to do four paintings, which were hung in the church the following spring. He then went to Chicoutimi, where he finished a canvas he had begun in Rome for the seminary chapel; the chapel was enhanced by a second work of his in the autumn. After selling a portrait of Pius X to the Séminaire de Québec, Huot rejoined his family in Brussels in May 1905. A perfectionist as a painter, he took classes again for seven months, this time with Jean Delville, senior professor at the Académie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique. Little is known about this sojourn. There is no doubt, however, that Huot lived in Saint-Malo, France, in the spring of 1907 and that his wife died on 28 June at a nearby beach resort. Huot returned to Quebec City with his daughter in August; he set up his studio on Rue Saint-Jean and quietly resumed his activities. He produced a few illustrations for the 1907 edition of Le May’s Contes vrais and drew the costumes and flags for the celebrations of Quebec’s tercentenary in 1908.

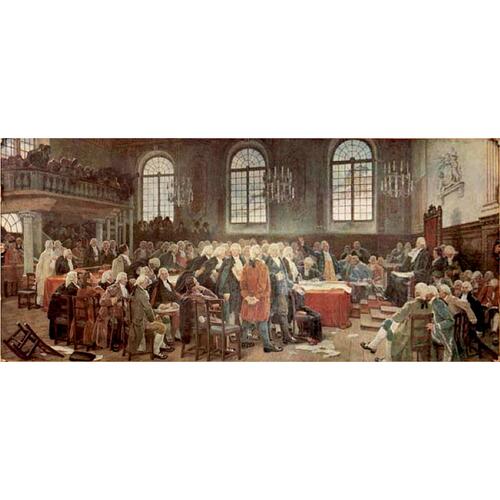

In his prime, Huot received the commission that painters in the province of Quebec had dreamed of for decades: to produce a historical painting for the legislative building. On 16 Aug. 1910, having been selected by a committee composed of Thomas Chapais*, Eugène-Étienne Taché, and Ernest Myrand, Huot agreed to paint an oil on canvas whose subject would be Le débat sur les langues: séance de l’Assemblée législative du Bas-Canada le 21 janvier 1793. The canvas would be glued onto the wall above the speaker’s chair in the chamber of the assembly. That Huot was awarded this contract was hardly surprising, for Quebec’s intellectual elite had supported him from the outset of his career, and he also had useful connections in the political milieu. Chapais was a personal friend (they attended the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière at the same time) and Jules Tessier, a Quebec lawyer and politician, had already obtained a studio for him in the legislative building. In addition, his conservative aesthetic was entirely pleasing to his contemporaries. Huot worked for three years on this mural, the sketch for which was finished in February 1911. A few months later he went to France to complete his historical research and to do certain tasks deemed necessary to create the work. Back home in November, he set himself up at the Quebec Technical School until January 1913 and then began to paint directly on the canvas glued onto the wall of the chamber of the assembly. Unveiled on 11 November, the work was such a tremendous success that the government quickly gave him a new contract. This time he was to paint an allegory based on the theme of Quebec’s motto, Je me souviens, to decorate the ceiling of the same room. Huot would spend years deciding on the composition of this work; he found it difficult to define its subject, which seemed neither to enthuse nor to inspire him. The painting would not be finished until December 1920.

While working on the sketches for Je me souviens, Huot accepted other commissions. In 1914 he drew an allegory of knowledge that would serve as the model for a stained-glass window in the legislative building’s library. He painted stations of the cross for the Sœurs de Saint-Antoine de Padoue in Chicoutimi in 1915, did seven paintings for the church of Notre-Dame parish in Hébertville the following year, and produced a few illustrations for Ulric Barthe’s work, Similia similibus ou la guerre au Canada: essai romantique sur un sujet d’actualité, which was published at Quebec in 1916. One project, however, held a special place in Huot’s life between 1910 and 1920: the decoration of the chapel at the Ermitage San’Tonio (in Lac-Bouchette). Out of friendship for Abbé De Lamarre, who wanted to establish a pilgrimage site there, Huot did 22 paintings for the chapel during his summer holidays.

Huot was reducing his activities by 1920. In 1924, however, he drew the medal commemorating the tercentenary of the consecration of New France to St Joseph, which Alfred Laliberté* rendered in relief. At the age of 71, he enthusiastically accepted a final contract from the government: Conseil souverain, a depiction of the first meeting of that body to decorate the Legislative Council chamber. In order to gather information, he spent the spring of 1927 in Paris. Huot worked on this painting until his death on 27 Jan. 1930. It would be completed by two students from the École des Beaux-Arts in Montreal and in Quebec City under the supervision of their respective principals, Charles Maillard* and Henry Ivan Neilson*. In March 1930 the French government would posthumously name Huot an officier de l’Instruction publique.

Charles Huot had many students, including Edmond Lemoine and Louise Gignac. He was a respected and admired man, whose conservative aesthetic met the expectations of his contemporaries. Posterity would be harsher on him, however; he would be criticized for his academicism and his work as a copyist. In fact, Huot’s oeuvre probably deserves to be re-evaluated in the light of new research and directions in the field of art history.

Several of Charles Huot’s religious paintings have been destroyed in fires, but those in the churches of Saint-Sauveur (Quebec), Saint-Joseph (Carleton, Que.), Saint-Patrice-de-la-Rivière-du-Loup (Rivière-du-Loup, Que.), and Notre-Dame (Hébertville, Que.) and in the chapel of Lac-Bouchette have survived. Examples of Huot’s work are also found in Quebec City in the legislative building, the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, the National Commission of Battlefields, and the Museum of Civilization, Dépôt du Séminaire de Québec; the Musée du Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean in Chicoutimi, Que.; the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; and the Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. Huot is the author of “Causerie artistique: l’œuvre de Tissot,” La Nouvelle-France (Québec), 2 (1903): 188–92. Despite extensive research, it has proven impossible to locate his marriage record.

ANQ-Q, CE301-S1, 10 avril 1855. Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, P 24 (fonds Charles-Huot). Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, dossier Charles Huot; Fonds Gérard-Morisset, dossiers Charles Huot et paroisses. L’Action sociale (Québec), 22 juill. 1908, 2 févr. 1911. Le Canadien (Québec), 15 mai 1876. Le Courrier du Canada (Québec), 9 déc. 1873; 2 mars 1881; 8 janv., 8 oct. 1888; 28 oct. 1889; 8 nov. 1890; 22 mars, 11–12 juill., 16 nov. 1892; 23 mai 1893; 8 févr. 1894; 8–9, 12, 22–23 mai 1900. Le Devoir, 28 janv. 1930. L’Électeur (Québec), 27 nov., 13 déc. 1890; 11 juill. 1892; 12 févr., 25 juill. 1894. L’Étendard (Montréal), 30 nov. 1886, 14 juin 1901. L’Événement, 27 sept. 1870, 6 déc. 1873, 6 avril 1875, 15 mai 1876, 23 mai 1900, 16 nov. 1911, 28 janv. 1930. Le Journal de Québec, 30 mai 1874; 15 mai, 16 sept. 1876; 19 mai 1877. La Minerve, 6 juin 1874; 16 juill., 6 août 1886; 4 févr. 1887. L’Opinion publique (Montréal), 15 mars 1877. La Presse, 26 mai 1900, 8 avril 1913, 13 nov. 1920, 20 janv. 1927. La Semaine commerciale (Québec), 6 mai 1898. Le Soleil, 25 mai 1900, 12 févr. 1930. Sylvain Allaire, “Élèves canadiens dans les archives de l’École des beaux-arts et de l’École des arts décoratifs de Paris,” Journal of Canadian Art Hist. (Montreal), 6 (1982), no.1: 98–111; “The Charles Huot paintings in Saint-Sauveur church, Quebec City,” National Gallery of Canada, Annual bull., 2 (1978–79): 17–30. Henri d’Arles [Henri Beaudé], Pastels (New York, 1905); Propos d’art (New York, 1903). Commission des Biens Culturels du Québec, Les chemins de la mémoire (3v., Montréal, 1990–99), vol.3 (Biens mobiliers du Québec, 1999). Robert Derome, “Charles Huot et la peinture d’histoire au Palais législatif de Québec (1883–1930),” National Gallery of Canada, Bull., 27 (1976); “Charles Huot, peintre traditionnel?” Vie des arts (Montréal), no.85 (hiver 1976–77): 63–65. “Description de la chapelle de S. Antoine,” Le Messager de Saint-Antoine (Chicoutimi), 7 (1901–2), no.10: 145–51. Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs de tous les temps et de tous les pays (nouv. éd., 10v., Paris, 1976), 5: 676. Ernest Gagnon, “M. Charles Huot et l’église de Saint-Sauveur,” Rev. canadienne (Montréal), 26 (1890): 463–65. Maurice Hébert, “Le soulier de satin; conte au coin du feu,” Le Canada français (Québec), 2e sér., 12 (1924–25): 673–81. Maurice d’Hesry, “Charles Huot et l’abbé Delamarre,” Saguenayensia (Chicoutimi), 2 (1960): 129–33, 142–48; 3 (1961): 3–10. J.-S. Lesage, Notes et esquisses québécoises; carnet d’un amateur (Québec, 1925). Hormisdas Magnan, Charles Huot, artiste-peintre, officier de l’Instruction publique: sa vie, sa carrière, ses œuvres, sa mort (Québec, 1932). Raymond Montpetit, “Un exemple de peinture d’histoire au Québec: Charles Huot à l’Assemblée nationale,” RHAF, 31 (1977–78): 397–405. J.-R. Ostiguy, Charles Huot (Ottawa, 1979); “Charles Huot raconte les miracles de saint Antoine de Padoue,” Vie des arts, no.87 (été 1977): 16–17.

Cite This Article

Joanne Chagnon, “HUOT, CHARLES (baptized Charles-Édouard-Masson),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/huot_charles_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/huot_charles_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Joanne Chagnon |

| Title of Article: | HUOT, CHARLES (baptized Charles-Édouard-Masson) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |