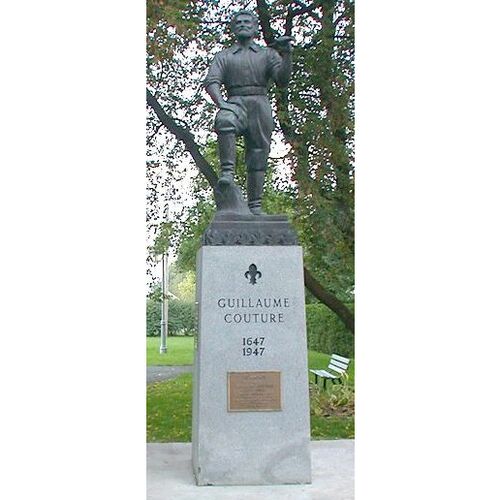

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

COUTURE, GUILLAUME (he sometimes signed himself Cousture), carpenter, a donné of the Society of Jesus, discoverer, interpreter, diplomat, judge of the seneschal’s court, first settler at Lévis; baptized 14 Jan. 1618 in the parish of Saint-Godard, Rouen (province of Normandy), son of Guillaume Couture and Madeleine Mallet; d. 4 April 1701.

It is impossible, by reference to existing documents, to determine the year of his arrival in New France. The Jesuits, who in their Relations never tire of praising his devotion and his courage, furnish no information on this point. The years 1639 and 1640 seem the most likely. He may have made the crossing in the spring of 1640 at the same time as René Goupil* and Father René Ménard*, and have undertaken to be an assistant to the Jesuits before he left France. His vocation as a donné may have been inspired by Goupil, who was already one. In an act dated 26 June 1641 at Quebec, in which he bequeathed to his mother and sister the modest amount of landed property left to him in France by his father, he styled himself “servant of the reverend Fathers of the Society of Jesus in the Huron mission in New France.” He set off shortly afterwards for Huronia, taking with him various items for the missionaries. It was the first of his long trips. He returned to Quebec the following spring, with Fathers Isaac Jogues* and Charles Raymbaut*, who was gravely ill; they were accompanied by a few indigenous chiefs, among whom was the famous Ahatsistari*. Altogether there were 25 travellers in 4 canoes.

Scarcely 15 days after their arrival, Jogues and Couture, accompanied this time by René Goupil, set out once more for the Huron country. The expedition was an important one, for the chiefs, who had come to Quebec on an official mission, were returning to their country at the same time, having been assured of the protection of the French authorities against their Iroquois enemies. On 1 Aug. 1642, 12 canoes, carrying some 40 persons, left Trois-Rivières. The departure did not escape the vigilant eyes of the enemy sentries. On the first evening of the journey, when the convoy had barely reached the entry to Îles-du-Sud in Lac Saint-Pierre, they halted for the night [see Ahatsistari]. The next day, at dawn, they were on the point of setting out when scouts discovered tracks on the shore. They started all the same, but less than half an hour later the little band heard firing and returned hastily to land. Goupil, a novice in forest lore, was quickly captured. Jogues, who had hidden for a moment in the undergrowth, surrendered himself to the Iroquois in order not to abandon his companions. Couture thought the missionary was in a safe place and managed to flee; but not finding him anywhere and not wanting to leave him, he returned towards the site of the ambush. On the way he encountered five Iroquois; one of them took aim at him but missed his target; Couture fired in his turn and killed his adversary. The four others captured him, and as the dead man was their chief Couture experienced Iroquois vengeance for the first time. His nails were torn out, his joints were broken, and then the palms of his hands were slowly pierced. One finger was sawn off with a shell. Couture bore all this without a cry, for not far away his companions were suffering in silence. The prisoners who had not been killed outright were borne off to the Mohawk villages, where further tortures awaited them. All were stripped naked, and were forced to pass between two rows of men armed with whips and clubs who struck them in turn. Couture headed this ghastly procession, which was repeated in each village.

In accordance with custom, Couture was turned over to the family of the chief whom he had killed so that they could dispose of him as they thought fit. He was made to witness the horrible death meted out to the chief Ahatsistari, details of which he later gave to Father Jogues. He was then adopted by a widow of the tribe, who dressed his wounds and treated him well. He was to acknowledge later to Jogues that, despite the proposals that were made to him, he remained faithful to his vows as a donné.

Goupil was murdered on 29 September 1642. Jogues succeeded in escaping in November 1643, with the complicity of the Dutch nearby, and eventually got to France. Couture could have joined him, but he did not want to compromise the missionary’s flight, and decided to wait for another opportunity. He continued to improve his knowledge of the Iroquois language, observe customs, and note particularly the intentions of the chiefs. He adapted himself readily to his new kind of life, and his peaceful attitude won him the confidence of the members of the council. One Relation mentions that “the Iroquois held him in esteem and high repute, as one of the first men in their nation. Consequently he assumed the position of a captain among them, having acquired this prestige by his prudence and wisdom.” Léo-Paul Desrosiers was correct in writing that “Couture is therefore the first Frenchman to win a great influence in the Iroquois country, after being adopted there, and, right in this enemy territory, to play a role favourable to France. Like several of his successors, he was to rise within this strange nation from the state of prisoner to that of chief.”

Thus in July 1645 he accompanied the chief Kiotseaeton*, the recognized diplomat and great warrior of the Mohawk tribe, to a council held at Trois-Rivières by the governor general, Huault* de Montmagny, and François de Champflour*, the commandant and local governor. Couture was dressed in Iroquois style, like his companions. He identified himself, but everyone, including Father Jogues, who had returned from France some time before, hesitated to recognize him, for all hope of seeing him again had been lost. “As soon as Couture was recognized,” notes the Relation of 1645, “each person threw himself on his neck. They looked on him as a man come back to life who gives joy to all who thought him dead, or at least in danger of spending the rest of his existence in a most bitter and barbarous captivity.”

It was indeed with a genuine desire for peace that the Mohawks brought back their precious prisoner, for Couture had convinced them of the friendly intentions of the French. But Couture’s idea went still further: he would have liked to be the instigator of a permanent peace between all the indigenous nations and the French colony. To this end he agreed to return with the Iroquois ambassadors, to try to encourage them to open serious peace negotiations with the Hurons.

When he returned in the spring of 1646 from this embassy to the Mohawks, Couture sought from the Jesuits authorization to break his vows as a donné, because he intended to get married: perhaps he wanted to marry an Iroquois girl with a view to strengthening the alliance between indigenous and white people. The superior, Jérôme Lalemant*, gave his consent on 26 April. Couture continued his peace parleys at Trois-Rivières and Quebec with the chiefs of the various nations. He was on the point of succeeding when on 18 Oct. 1646 Father Jogues, who since his escape had returned twice to the Mohawks as an emissary, and his companion Jean de La Lande* were murdered. Negotiations were broken off. The Algonkins and Hurons were secretly delighted, for they alone would retain the friendship of the French. Couture, in no way discouraged, went to the Huron country in 1647 to try to renew the treaties of alliance. His efforts were fruitless, but on his return the population of Trois-Rivières and loyal aboriginals welcomed him warmly at the instigation of Father Jacques Buteux*, who had a high regard for him and who in a report dated 1652 called him “the worthy Couture.” A similar welcome was given him at Sillery, “with joy on the part of all the Huron, Algonkin and Anniehronnon [Mohawk] Indians,” as the Journal des Jésuites noted.

In this same year, 1647, Couture entered into partnership with François Byssot* de La Rivière, and went to settle at Pointe-Lévy, on the Lauson seigneury. He agreed to clear a tract of land and erect a main building for his partner, the latter providing the money and materials. The building was finished in the autumn; Byssot gave Couture 200 livres for his work, and allowed him to remain in the house until he had completed his own dwelling on a neighbouring piece of land. On 15 Oct. 1648 both obtained official title to their land grants from the seigneur, Jean de Lauson*. On 18 Nov. 1649 Couture married Anne, one of the three Esmard sisters, who had come together from Niort, in the province of Poitou. (The others were Barbe, wife of Olivier Letardif*, and Madeleine, wife of the son of Zacharie Cloutier*.) The marriage ceremony, presided over by Abbé Le Sueur*, took place “in the house of the said Sieur Couture at Pointe-Lévy,” according to the register of the Roman Catholic church in Quebec.

Although Couture wanted to stay quietly on his property and make it bear fruit, his knowledge of indigenous languages and his experience of life in the woods were often made use of by the authorities. There can be no doubt that in the relation of Father Buteux the detailed part that concerned Father Jogues’ captivity was to a large extent inspired by Couture. Apart from a few Hurons, he was the sole witness of it. He was called upon in 1657 to be an interpreter for the founding of a mission among the Onondagas, a mission earnestly requested by the tribe itself. In 1661 he agreed to take part, along with Fathers Gabriel Druillettes* and also Claude Dablon*, Denis Guyon, and François Pelletier, in an expedition sent by Governor Voyer d’Argenson to discover the northern sea. The guides, dreading the presence of Iroquois in the region, abandoned the French at the watershed. Two years later Couture accepted Governor Dubois* Davaugour’s invitation to assume command of an expedition to accompany “the Indians northwards as far and as long as he shall deem it expedient for the service of the king and the good of the country: and he may go himself or send others to winter with them, if he thinks that his own safety may thereby be ensured and that some public advantage may ensue.” The expedition was an important one: to find an inland route to the northern sea. Two Frenchmen, Pierre Duquet*, later a notary, and Jean Langlois, a shipwright, accompanied Couture; the others were indigenous men. In all there were 44 canoes. In an affidavit which he swore in 1688, Couture went over the itinerary they had followed: the group left Quebec in mid-May, started up the Saguenay River, and reached Lake Mistassini on 26 June. A sudden storm left a foot of snow. The group pushed on, and reached a river [Rupert] “that empties into the Northern Sea.” The French were unable to continue on their route, for the guides refused to go any farther. Couture thus affirmed in 1688 that in 1663 he was unable to make his way to the northern sea. Nevertheless, this daring expedition permitted him to become acquainted with the vast region to the north of the St Lawrence, a region peopled with tribes whose customs were very different from and more peaceful than those of the Iroquois and Hurons. In 1665 he arranged with Charles Amiot*, Noël Jérémie*, and Sébastien Prouvereau that they would accompany Father Henri Nouvel, who was going to preach the gospel to the Papinachois. The following year he was delegated by the governor to go to New Holland to protest against the murder of two French officers by the Mohawks. He went to the Iroquois and ordered them to hand over the murderers, under threat of a punitive expedition. He returned to Quebec on 6 September with two Mohawks, one of whom was the leader of the group that had killed Lieutenant Chazy.

This episode marks the end of Guillaume Couture’s adventurous career. From that time on he seldom left his domain at Pointe-Lévy. The 1667 census places him there, with his wife and nine children. He had 20 acres under cultivation and 6 head of cattle. In turn or simultaneously he held the most important offices in the seigneury: captain of the militia, clerk of court, “judge of the seneschal’s court for the Lauzon shore.” According to an act of 16 Nov. 1684, drawn up by Nicolas Métru, he may also have acted as a notary. In 1675 he requested a resident parish priest for the seigneury, where the copyholders were beginning to be numerous. Owing to the scarcity of priests, he did not obtain one until 1690. Through these different sources, one can feel that he was the moving spirit of the newly formed seigneury. Yet in the 1681 census he reported only the humble title of carpenter.

One can give only an approximate idea of the last years of his life, which were those of an ordinary settler of the earliest period. The attack on Quebec by Phips* in 1690 put the inhabitants of the south shore of the St Lawrence in a state of alert. It is probable that the former hero did not dissociate himself from the defence plans, but we have no precise indication as to his participation in them. The archives of the Conseil Souverain have preserved the details of misunderstandings that arose sometimes between Couture and Byssot, at other times between the two pioneers and the other copyholders of the seigneury. An analysis of these documents clearly indicates that Couture did not seem to be easy to get along with, and that he intended to see that his rights were respected. According to the same documents, he appears sometimes to have exceeded his prerogatives as judge and captain of the seigneury. Nonetheless, on several occasions he was invited to sit on the Conseil Souverain, in the absence of regular members. Meanwhile the majority of his ten children had formed connections by marriage with people of good family. Thus, in 1678 Marie married François Vézier, and five years later Claude Bourget; in 1680 Marguerite married Jean Marsolet, son of Nicolas Marsolet* de Saint-Aignan; in 1688 Louise married Charles-Thomas Couillard de Beaumont.

His wife, Anne Esmard, was buried at Pointe-Lévy on 15 Jan. 1700. On 28 June following, Guillaume Couture acknowledged that he owed to “his younger son” Joseph-Oger Couture, Sieur de La Cressonnière, the sum of 600 livres for having assisted his father and mother during the last six years, and “even long before.” He died on 4 April 1701. On 14 November an inventory was made of the possessions of “the late Guill. Couture, during his lifetime judge of the seneschal’s court for the Lauzon shore, and Anne Hemard.” We do not know the place where this hero of the early days of the colony is buried.

JR (Thwaites). JJ (Laverdière et Casgrain). Jug. et délib., I, 417, 438; II, 674. Ici ont passé (Société hist. du Saguenay pub., II, Chicoutimi, 1934). Jean Delanglez, Louis Jolliet, vie et voyages (Montréal, 1950). L.-P. Desrosiers, Iroquoisie (Montréal, 1947). Archange Godbout, Les pionniers de la region trifluvienne (Trois-Rivières, 1934). J.-E. Roy, Le premier colon de Lévis: Guillaume Couture (Lévis, 1884). F.-X. Talbot, La vie d’Isaac Jogues: un saint parmi les sauvages (Paris, 1937). Lucien Campeau, “Un site historique retrouvé,” RHAF, VI (1952), 31. Jean Côté, “L’institution des donnés,” RHAF, XV (1961), 344–78. Archange Godbout, “Les trois sœurs Esmard,” SGCF Mémoires, I (1944–45), 197–200.

Revisions based on:

Arch. départementales, Seine-Maritime (Rouen, France), “État civil,” Rouen (paroisse Saint-Godard), 14 janv. 1618 : www.archivesdepartementales76.net (consulted 31 Oct. 2017). Arch. du Monastère des Augustines (Québec), F5 (fonds Hôpital du Monastère des Augustines de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec), G1, 2/1: 2 (reg. des malades, vol. 2 (1698–1709)), p.60. Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Québec, CE301-S1, 18 nov. 1649.

Cite This Article

Raymond Douville, “COUTURE (Cousture), GUILLAUME (d. 1701),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/couture_guillaume_1701_2E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/couture_guillaume_1701_2E.html |

| Author of Article: | Raymond Douville |

| Title of Article: | COUTURE (Cousture), GUILLAUME (d. 1701) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1969 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |