Source: Link

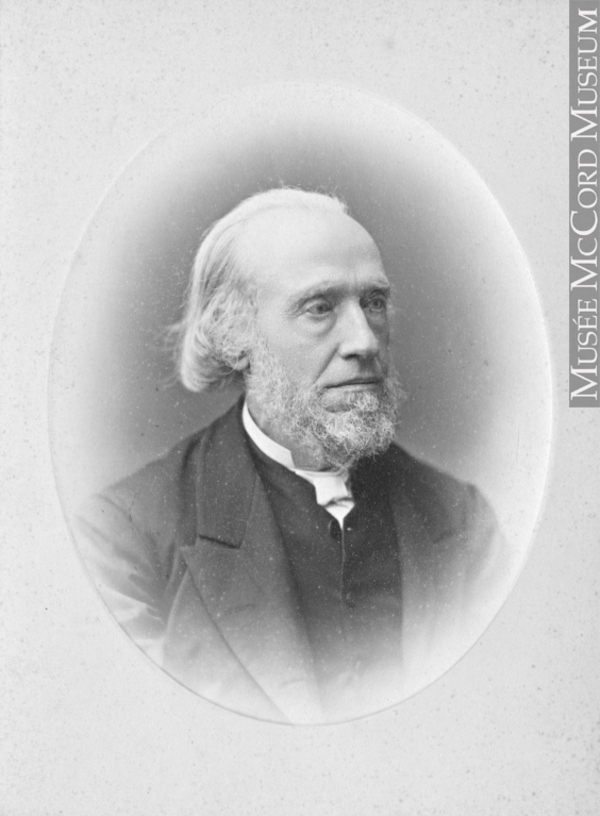

CORDNER, JOHN, Unitarian minister, editor, and author; b. 3 July 1816 in Ireland, son of John Cordner, clockmaker, and Mary Neilson; d. 22 June 1894 in Boston, Mass.

John Cordner grew up in Newry (Northern Ireland), although he may have been born in Hillsborough. The Irish Presbyterian Church of his upbringing was the scene of increasingly acrimonious polarization between orthodox Calvinists and liberals. Many of the latter were avowedly Arians or Unitarians, and were also political radicals. They were ousted from the main Presbyterian body in 1829 and established their own Remonstrant Synod of Ulster. It was for ministry in this body that Cordner, after having spent some time in business at Newry, prepared himself at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution. In 1843, the year he completed his studies, Cordner’s supervisor, Henry Montgomery, received a request for help in finding a minister for the recently established Unitarian Society of Montreal, the only Unitarian congregation in the Canadas. Cordner was persuaded to accept this pioneering role and was ordained in Ireland on 12 September, the same day on which the Montreal congregation became a member of the Remonstrant Synod of Ulster. He arrived in Montreal on 4 November.

Cordner launched his ministry with a welter of activities. To clarify, defend, and disseminate Unitarian views, he began a monthly journal, the Bible Christian (Montreal), in 1844. Having attracted new members, and with a congregation numbering 200 in which the business community was prominently represented, he initiated construction of a church on Beaver Hall Hill; the handsome structure, seating 450, was opened in 1845. That year Cordner obtained the right, through legislation, to hold baptismal, marriage, and burial registers on behalf of his congregation. In 1845 as well he travelled to Toronto to launch a congregation there. Early the following year, in Montreal, he delivered a well-advertised series of doctrinal lectures, which attracted large audiences and provoked a storm of denunciations from Protestant pulpits and newspapers.

The statements that drew such a response were conservative enough by Unitarian standards, Cordner’s religion being Bible-centred. However, Montreal in 1846 was not prepared to hear that reason must be the final arbiter in religious belief, that God is an undivided unity, that Jesus was a human being (though divinely commissioned), and that his death was significant as an example of fidelity to principle at all costs rather than as an atoning sacrifice for sin. No less shocking was Cordner’s rejection of the doctrine of original sin in favour of a conception of human nature as open to continuous progress under providential guidance. Roman Catholics, mindful of the contribution Unitarians had made toward establishing their civil rights in the British Isles and New England, did not join in the denunciations by Protestants.

Cordner’s views were generally congenial, however, to the leading figures in commercial and political life who comprised the nucleus of the Unitarian Society, among them Adam Ferrie*, Francis Hincks*, Luther Hamilton Holton*, John Young*, Benjamin Holmes*, Harrison Stephens*, Theodore Hart*, and Benjamin, Thomas*, and William* Workman. Cordner’s teachings largely harmonized with their emphasis upon freedom of the individual, self-reliance, and the possibility of progress through human effort. Capitalism as such he defended as a great advance over the restrictive feudalism that had preceded it, but the wealth it produced, he argued, should be used responsibly for the benefit of all, particularly the less fortunate.

This moral approach to economics and politics led Cordner to take strong stands on most issues of the day. For example, despite opposition by most Montreal merchants, including Stephens, to the British movement towards free trade in the 1840s, Cordner joined Holton and Young in defending it, in part on the grounds that it would render food cheaper for the needy and increase commerce among nations, thus reducing the risk of class and national conflicts. Nothing, indeed, was closer to Cordner’s heart than the cause of world peace; in 1849 he was a delegate to the peace congress in Paris. He vigorously denounced imperialism and in particular British rule in India and his native Ireland. He championed women’s rights, non-sectarian public education, a more humane penal system, and a more compassionate approach to care of the mentally ill. He supported American Unitarians in their campaign against slavery and was a major speaker at a great rally in Montreal in 1861 to protest the proposed extradition of a runaway slave. Although self-interest led many Montreal businessmen to favour the South in the American Civil War, Cordner rallied opposition to Southern attempts to embroil Britain in armed conflict with the Union government. In 1867 he gave an outspoken address to the Institut Canadien of Montreal in which he promoted openness of mind and spirit to new ideas and to peoples of other cultures, attacked censorship, and lauded the institute and its library as flagships of liberty and toleration in a war “against the exclusiveness and domination of ultramontanism.” The invitation to speak and the use he made of it contributed, no doubt, to the deterioration of relations between the Institut Canadien and Bishop Ignace Bourget*.

Aggressive promotion of his causes, coupled with the backing of influential members of his congregation, made Cordner a force to be reckoned with. He continued to edit the Bible Christian until its end in December 1848, and five years later he founded another monthly, the Liberal Christian, which he used as a forum until 1858. Although reserved about his personal history, experiences, and feelings, and disconcertingly taciturn in social situations, he could soar to passionate eloquence when pleading a cause from pulpit or platform.

On his arrival in North America, Cordner had established excellent relations with the thriving American Unitarian movement, especially with New England Unitarians; indeed they had paid nearly half the cost of constructing his church. His marriage in Boston on 20 Oct. 1852 to Caroline Hall Parkman, sister of the historian Francis Parkman, cemented these ties (they would have three daughters). In 1854, at Cordner’s invitation, the annual Autumnal Unitarian Convention brought to Montreal some 300 delegates from all over North America, including significant American intellectual, social, and political figures. Within the Unitarian Society, however, Benjamin Workman viewed with alarm this shift of the congregation’s connections from Ireland to the United States and sought to oppose it. In 1856 Cordner forced the issue to a head by resigning; the congregation refused to accept his resignation and instead withdrew from the Remonstrant Synod of Ulster.

By the 1850s, in fact, Cordner and the Unitarian Society were prospering together. They had been pointedly ostracized in 1846 when the Protestant churches of the city established the Strangers’ Friend United Society, but after the famine in Ireland the following year Cordner became a leading figure in organizing relief. In 1852 he had a prominent role in the establishment of Mount Royal Cemetery, and 11 years later he was welcomed among the incorporators of the Montreal Protestant House of Industry and Refuge. Apart from Cordner’s personal efforts, the convention of 1854 and the economic prosperity of the 1850s, which was reflected in the growth and increasing affluence of the Unitarian Society, account for its gradual acceptance in Montreal religious circles. In 1857 the congregation decided to erect a new church; the old one, although large enough, was not sufficiently imposing. This time no outside funding was required. The building, named Church of the Messiah on the example of several in the United States, was first used at Easter 1858. After it was damaged by fire in 1869 the Unitarians accepted the invitation of the Irish Roman Catholic priest Patrick Dowd to worship temporarily in rooms at St Patrick’s Church. The following year Cordner was honoured by McGill College with a degree of lld.

Although increasingly continentalist in outlook, Cordner asserted that “our nationality as it grows must savor of the soil on which it grows,” and he insisted that the funds sent by his congregation to the American Unitarian Association be used for ministry in the Canadas. He saw in the province of Canada, and later in the country, a divinely provided opportunity for building a righteous nation, and he attacked as apostasy the politics of expediency practised by Sir John A. Macdonald as well as the popular enthusiasm for material progress regardless of human cost. He was, however, silent on confederation, over which his congregation was divided.

Since 1858 Cordner had increasingly suffered from poor health, and from 1872 only the insistence of his congregation that he remain prevented his retirement. It was finally accepted in 1879, and three years later he moved to Boston; there he could enjoy a milder climate, Parkman’s company, and the companionship of many Unitarian colleagues, while working on a limited scale for his denomination. In June 1894 he died at his home on Chestnut Street of “old age prostatic disease” and “hypostatic congestion of the lungs.” Though he had claimed in 1851 to be no lover of controversy, Cordner had spent the greater part of his ministry in Montreal in the thick of it, and he continued to write on controversial issues until shortly before his death.

In addition to editing the Bible Christian (Montreal) and the Liberal Christian (Montreal), John Cordner wrote at least 120 articles, pamphlets, and books, some of which have particular importance because of their influence or because of what they reveal of Cordner’s ideas and beliefs. His articles in the Bible Christian include “The moral results of unrestricted commerce,” 3 (August 1846): 2; “Public opinion in Montreal,” 5 (January 1848): 3; “Popular power and its proper guidance,” 5 (April 1848): 3; “The university question,” 5 (May 1848): 3; and “Protestantism,” 5 (September–October 1848): 3. Other articles which should be noted are “Unitarianism in Canada,” Unitarianism exhibited in its actual condition . . . , ed. J. R. Beard (London, 1846) ; 83–87; “L’hospitalité de l’esprit,” Institut canadien, Annuaire (Montréal, 1867), 9–14; and “The railway scandal and the new issue,” Montreal Herald, 19 Aug. 1873. His pamphlets include A pastoral letter to the Christian congregation assembling for worship and education in the Unitarian Church, Montreal (Montreal, 1853); The foundations of nationality . . . (Montreal, 1856); The Christian idea of sacrifice: a discourse preached at the dedication of the Church of the Messiah, Montreal, on Sunday, 12th September 1858 (Montreal, 1858); Righteousness exalteth a nation . . . (Montreal, 1860); The providential planting and purpose of America (n.p., n.d.); The American conflict . . . (Montreal, 1865; repr. as Canada and the United States . . . , Manchester, Eng., 1865); Is Protestantism a failure? . . . (Montreal, 1869); and A letter to Geo. W. Stephens, esq. (Boston, 1892). His book Twenty-five sermons . . . (Montreal, 1868) contains several of these publications. Some important articles, published in unidentified newspapers and assembled in a scrapbook at the Unitarian Church Arch. (Montreal), Church of the Messiah, are “Wisdom is better than weapons of war” (1857); “Royalty and its recognition” (28 Aug. 1860); “The true purpose of the Christian Church” (4 April 1876); “Rights of tenant farmers in Ireland” (24 Dec. 1879); and “Forty-one years” (October 1884). Portraits of Cordner are at the Unitarian Church Arch.

Boston, Registry Division, Records of births, marriages and deaths, 22 June 1894. Private arch., Phillip Hewett (Vancouver), Mary Lu MacDonald, “John Cordner” (typescript). Unitarian Church Arch., Church of the Messiah, E. A. Collard, manuscript history of the church, 1984; W. N. Evans, manuscript history of the church, 1892. Christian Inquirer (New York), 8 May 1858. Christian Register, Unitarians (Boston), 28 June, 5 July 1894. Montreal Herald, 20 April 1872. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), 1: 98–99. Phillip Hewett, Unitarians in Canada (Toronto, 1978).

Cite This Article

Phillip Hewett, “CORDNER, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cordner_john_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cordner_john_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Phillip Hewett |

| Title of Article: | CORDNER, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |