Source: Link

DOUGLAS, GEORGE, Methodist minister and educator; b. 14 Oct. 1825 in Ashkirk, Scotland, youngest of three sons of John Douglas and Mary Hood; m. 28 Nov. 1855 Maria Bolton Pearson in Toronto, and they had four daughters, one of whom died in childhood; d. 10 Feb. 1894 in Montreal.

In the company of his mother and two elder brothers, George Douglas arrived at Montreal in July 1832 to join his father, who had immigrated the previous year following a decline in his fortunes as a miller in Scotland. Douglas attended the British and Canadian School in Montreal and a private school in La Prairie before taking a job as a clerk in a Montreal bookstore. Hoping to become a marine engineer, he entered the ironworks of Sutherland and Burnett and attended design classes in the evening; delicate health later forced him to abandon this ambition.

Although Presbyterian in tradition, the family eventually became adherents of the Methodist St James Street Chapel. There young Douglas experienced conversion at a series of revival meetings held in 1843. Despite a retiring nature, he accepted the office of class leader, displaying – in the words of a contemporary – an “extraordinary gift of language and rare ability in the exposition of Scripture, together with a keen spiritual insight.” In 1847 he became a local preacher; the next year he was received on probation for the ministry of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. Determined to augment his rudimentary education, he left for England in December 1849 to attend the Wesleyan Theological Institution in Richmond (London). Immediately upon arrival, however, he was appointed to missionary work; on 1 March 1850 he was specially ordained prior to sailing for Bermuda. His term there was cut short by malaria, and he returned to Montreal in the spring of 1851. While recuperating, he attended lectures in medicine at McGill College, and he resumed his ministerial work the following year.

Beginning in 1854 Douglas received consecutive three-year appointments in Upper Canada to Kingston, Toronto, and Hamilton, before a relapse of malaria in 1863 forced him to take a year’s leave. The nerves and muscles of his hands atrophied so badly that he was subsequently unable to write without the aid of a mechanical device. His eyesight also deteriorated, and by 1877 he had to rely on his wife and daughters to read to him. Despite these handicaps, he returned in 1864 to the full-time pastorate in Montreal and emerged as one of the best known and most highly respected ministers in the country. He was awarded an honorary lld by McGill in 1870 and an honorary dd by Victoria College (Cobourg) in 1883. In 1876 a church in the west end of Montreal was named in his honour.

Although Douglas lacked a college education, he had managed, by dint of a phenomenal memory and constant application, to acquire a reputation for broad and comprehensive knowledge. When, in 1872, prominent Montreal Methodists such as James Ferrier* gained approval for a theological college in the city, Douglas was appointed principal and professor of theology. In the fall of 1873 Wesleyan Theological College opened with six students in the basement of Dominion Square Methodist Church; under Douglas it became a degree-granting institution affiliated with McGill, and by 1894 it boasted 72 students and 4 professors. Like many devout Protestants of his time [see Sir John William Dawson], Douglas feared that new trends in philosophy and science were “driving the ploughshare through all systems of thought.” Methodist institutions of higher learning could, he felt, protect society from unsettling scepticism by sending out “sons of the Church, armed with culture and science from its Christian standpoint,” who would meet the challenge of “the great electric twentieth century rising . . . like a mighty colossus with its swinging gait, with its resonant tread, with its eagle questioning eye, and its tremendous energy.” In training men for the ministry, Douglas struggled to balance the need for increasingly specialized learning and sympathy for contemporary issues with the retention of evangelical simplicity and enthusiasm.

Referred to by Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*] as “the Bismarck of Canadian Methodism,” Douglas was an ardent advocate of the movement in the second half of the 19th century to reunite its various branches in Canada. He rejoiced at the progress of Methodism relative to other Protestant denominations but felt that the church could not afford to be complacent in view of the growing strain placed on its spiritual and financial resources by the needs of both urban and frontier communities.

Known for his executive and administrative ability, he served as president of the Montreal Conference (1877) and vice-president (1874) and then president (1878) of the General Conference of the Methodist Church of Canada. His involvement with the Young Men’s Christian Association, the Evangelical Alliance, the Epworth League, and ecumenical Methodist conferences earned him an international reputation as a speaker.

Indeed, it was as the “Chrysostom of Canada” that Douglas gained his highest acclaim. His sermons were marked by strong argument, striking imagery, and eloquent phrasing. Douglas personified that combination of conservative theology and concern for holy living which was an important element within 19th-century Canadian Methodism. His was the uncompromising piety of an Old Testament prophet, and the Reverend Hugh Johnston recalled that “his rebukes scorched as with a flame of fire and fell like hot thunderbolts upon the dishonest and the corrupt.” He was especially outspoken in his condemnation of the theatre, modern novels, the liquor trade, political corruption, and divorce.

In the 1890s this concern with social purity prompted Douglas to become a prominent spokesman for the White Cross movement, which aimed to “protect the family in its integrity and virtue.” Like many reformers of the age, he placed great faith in “the ever-ascendant power of woman for good.” He recognized that one of the strengths of the Methodist Church was the active role that women had often played in its ministry. Although adamant in his condemnation of birth control, he championed access for women to higher education and the professions in order that they might gain “equality of independence.” “Give her but time,” Douglas asserted, “give her the ballot, give her the recognition that is coming on apace, and woman . . . will regenerate and cleanse political life, and put the impress of her purity, her elevation, on all that pertains to the recovery of this world for God.”

In Douglas’s opinion, the spiritual progress of the nation was also seriously endangered by “the subtle aggressions of Rome.” He used the facilities of the Wesleyan Theological College and of the French Methodist Institute, which he helped establish in Montreal in 1880, to train missionaries to proselytize the French Canadians. Alarmed by the close ties between the government of Honoré Mercier and the Roman Catholic hierarchy, he viewed the passage of the Jesuits’ Estates Act in July 1888 as a harbinger of the triumph of ultramontanism. An impassioned speech by Douglas helped persuade the Montreal Conference of the Methodist Church to protest both the act and the federal government’s refusal to disallow it. In July 1889 he was instrumental in founding a Montreal branch of the Equal Rights Association [see D’Alton McCarthy], which had been set up the previous month in Toronto to orchestrate a campaign against the act and its implications. Two years later he created a national sensation by denouncing Sir John Sparrow David Thompson as a “clerical creation” in league with the Jesuits and, therefore, an unfit successor to Sir John A. Macdonald as prime minister of Canada. Douglas’s censure of the Jesuits’ Estates Act and his support for the Manitoba School Act of 1890 were applauded and emulated by many prominent Methodists, but his very personal attack on Thompson’s morality was less well received.

On 10 Feb. 1894 Douglas succumbed to pneumonia and, following a simple service, he was buried in Mount Royal Cemetery. Although his candour had engendered considerable controversy, he had been almost universally admired for his uncomplaining endurance of physical affliction and his unwavering commitment to righteousness.

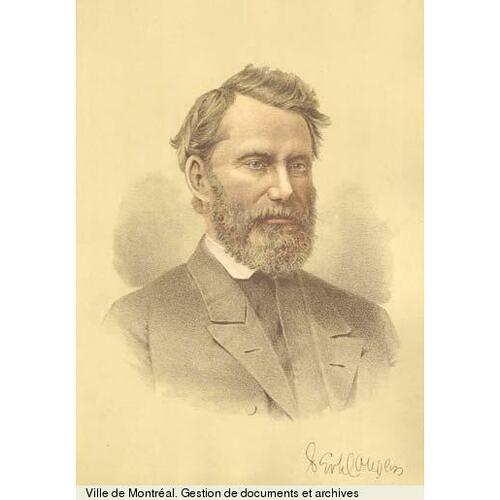

George Douglas is the author of Memorial of Rev. George McDougall, Indian missionary to the Saskatchewan, with his last two letters . . . (Montreal, 1876); Discourses and addresses (Toronto, 1894); Thou art the man! (Toronto, 1895); and, with William Morley Punshon*, A sermon in memory of the late Rev. Robert Watson Ferrier, M.A. . . . together with an obituary notice and a minute of the Montreal District meeting (Montreal, 1870). Portraits of Douglas appear in Discourses and addresses; Dent, Canadian portrait gallery; Montreal Daily Star, 12 Feb. 1894; and Cornish, Cyclopædia of Methodism.

ANQ-M, CE1-109, 13 févr. 1894. GRO (Edinburgh), Ashkirk, reg. of births and baptisms, 25 Nov. 1825. UCC, Montreal-Ottawa Conference Arch. (Lennoxville, Que.), M/50/1. UCC-C, Biog. files. French Methodist Institute, Annual report (Montreal), 3 (1883). Methodist Church (Canada, Newfoundland, Bermuda), General Conference, Journal of proc. (Toronto), 1890; Montreal Conference, Minutes (Toronto), 1889, 1894. Methodist Church of Canada, General Conference, Journal of proc. (Toronto), 1878. W. I. Shaw, “Memories of the Rev. Dr. Douglas,” Methodist Magazine (Toronto and Halifax), 39 (January–June 1894): 336–39. W. H. Withrow, “Death of Dr. Douglas,” Methodist Magazine, 39: 305–7. Christian Guardian, 4 Dec. 1855; 13 March, 12, 17, 19 June 1889; 14, 21 Feb. 1894; 3 Feb. 1904; 12 Sept. 1906; 18 March 1914. Gazette (Montreal), 6 July 1889. Montreal Daily Witness, 24 Dec. 1892; 12 Feb., 13 March 1894. Appletons’ cyclopædia (Wilson et al.), vol.2. Wallace, Macmillan dict. Frost, McGill Univ. N. H. Mair, The people of St James, Montreal, 1803–1984 ([Montreal, 1984]). J. R. Miller, Equal rights: the Jesuits’ Estates Act controversy (Montreal, 1979). Waite, Man from Halifax.

Cite This Article

Katherine Ridout, “DOUGLAS, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/douglas_george_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/douglas_george_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Katherine Ridout |

| Title of Article: | DOUGLAS, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |