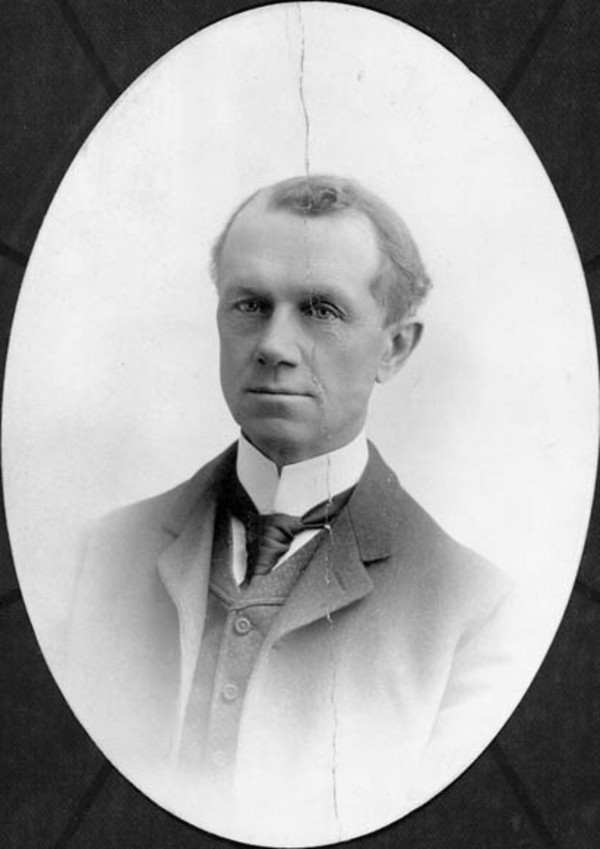

WATEROUS (Waterhouse), CHARLES HORATIO, manufacturer; b. 29 Sept. 1814 in Burlington, Vt, son of Eleazer Waterhouse and Emma Johnson; m. 5 Dec. 1839 Martha June, and they had six sons and a daughter; d. 10 Feb. 1892 in Brantford, Ont.

Charles Horatio Waterous’s father, a former principal of an academy at Burlington, died in 1816, shortly after he had abandoned his family and moved to St Louis. His widow struggled through financial difficulties until 1821, when she married Denson Tripp, a farmer at New Haven, Vt. From then until his 15th year, Charles worked summers on his stepfather’s farm and attended school in the winters. In 1829 he was apprenticed to Thomas Davenport, a blacksmith in Brandon, Vt. Waterous later remarked that his master was a “better inventor than blacksmith” and, when Davenport went out of business, he finished his training in a machine-shop.

Waterous’s apprenticeship had piqued his inventive curiosity and alongside his subsequent work as a machinist he continued to assist Davenport in experiments to develop an electric motor. In 1833 Waterous went to work in an uncle’s foundry and machine-shop in New York City. Over the next two years he was employed in machine-shops in Ohio. He then worked as an engineer on Great Lakes steamers. In January 1839 Davenport’s offer of a partnership drew Waterous back to New York City, where the inventor had established a workshop and laboratory. Their shop was above that of Samuel Finley Breese Morse, the perfecter of the telegraph, with whom Waterous later claimed to have discussed various technical problems. Unlike their neighbour, Davenport and Waterous were not successful: their motor, though capable of driving a small printing-press, lacked sufficient power for other industrial applications and was too expensive to produce. After a year, his savings depleted, Waterous borrowed money from friends to return to Ohio. He rented a machine-shop and ran his own business in Sandusky. Then, in 1842, with Julius Edgerton he constructed mills in and around Painesville; a fire in 1845 put them out of business. Again Waterous found employment on lake steamers. In 1846, however, he became a partner in a foundry in Buffalo with Edgerton and John D. Shepard, but the firm failed during the commercial depression of 1848.

Later that year Waterous accepted an offer to help reorganize the foundry business of Philip Cady Van Brocklin in Brantford. Although he probably brought little or no capital to it, he was made a partner and given a salary plus a quarter share of the profits. His technical expertise and innovative ability made it possible to transform the foundry into a factory producing steam-engines. Capital for this purpose was provided by another new partner, Thomas Winter, an Englishman recently arrived from the West Indies. Van Brocklin, Winter and Company continued until the retirement of its senior member in 1855. Unable to maintain the business on his own, Waterous entered a partnership that year with another Brantford foundry firm, Goold, Bennett and Company, to purchase the Van Brocklin works. His new partners were Franklin P. Goold and Adolphus B. Bennett, in Brantford, and Joseph Ganson, Holester Lathrop, and Ralph W. Goold, operators of a foundry in Brockport, N.Y. The new firm was named Ganson, Waterous and Company. Additional capital for plant expansion came from Brantford’s leading merchant, Ignatius Cockshutt*, who, though not a partner, was a co-owner of the factory.

The depression that began in 1857 nearly ended the business. Initially, customers’ remittances were sufficient to cover the purchase of raw materials, payrolls, and other expenses. But after 1857 the company suffered from a want of operating capital and, although the partners were generally considered wealthy, their assets increasingly became tied up in the business’s overdue accounts. In consequence, in 1857 Goold, Bennett and Company sold its original foundry, in Brantford, and by the end of the year Bennett, Lathrop, and R. W. Goold had withdrawn from Ganson, Waterous and Company. By 1859 the firm was unable to meet its obligations and began to liquidate its affairs. Its creditors, however, granted a last-minute reprieve in early 1860 in the form of a four-year extension of debt in return for an assignment of assets. Nevertheless, Ganson dissolved his connection in 1862, although to sustain public confidence the company’s name remained unchanged until 1864. That year, following the firm’s apparent repayment of its creditors and resumption of control, F. P. Goold left to run the Brantford Pottery, a business that he and Waterous had purchased in 1859 and continued to own until 1867, perhaps as a hedge against the failure of the foundry.

Waterous, however, decided to stick with the business, which he ran in partnership from 1864 with George H. Wilkes, forming a new firm, C. H. Waterous and Company. Wilkes had been a partner in Ganson, Waterous and Company since 1861, when it merged with another failed Brantford foundry whose creditors had employed him as manager. From the mid 1860s C. H. Waterous and Company prospered through the manufacture of grist-milling and sawmilling machinery, steam-engines, and pumping equipment for the petroleum industry in western Ontario and for municipal waterworks. Increased sales, from $120,000 in 1870 to $220,000 in 1875, justified ambitious plans for expansion, as well as the incorporation of the Waterous Engine Works Company Limited in 1874. The long and continuing financial participation of Ignatius Cockshutt was acknowledged in the selection of his son, James G., as president of the new corporation, with Waterous as general manager.

The depression of the mid 1870s deflated the optimism engendered in this reorganization. Only the foundations of a new factory had been laid before financial exigency forced the company to sell the land and remaining building material in early 1877. For protection, Waterous prudently complicated his personal finances by selling and mortgaging his property to his wife and children. Wilkes and J. G. Cockshutt lost interest in the business and in September 1879 Waterous, though still indebted to the senior Cockshutt, purchased all outstanding shares.

These difficulties, however, did not convert Waterous to support for protective tariffs as a solution to economic distress. Nor did he credit the impressive growth of his company from the late 1870s to the National Policy, introduced by the government of Sir John A. Macdonald in 1879 [see Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley]. During the 1880s Waterous negotiated with and obtained from the city of Brantford cash bonuses, tax remissions, and free utilities. In 1883 he sent his son Frank to Winnipeg to open and manage an agency and machine-shop to serve western customers. Since it employed only ten men, the branch probably simply managed regional accounts, erected and assembled mills and boilers, and undertook repair work. Three years later it was reduced to a sales agency and the machine-shop was closed when Waterous Sr decided to move into the American market. Responding to the lobbying efforts of the chamber of commerce in St Paul, Minn., the Waterous company opened a machine-works there under the management of another son, Frederick, who had been the assistant manager in Winnipeg. By 1888 the company employed 250 men and claimed, probably with some exaggeration, assets worth $750,000 including the plant in St Paul. Future growth, Waterous argued in 1891, depended upon the negotiation of a reciprocity treaty to open up the American market to Canadian manufacturers.

Waterous’s pronouncements on tariffs and reciprocity, usually in the Brantford Expositor, and his support of the Liberal party were the extent of his public involvement. For most of his life he belonged to the Congregational Church, but in later years he attended William Cochrane’s Zion Presbyterian Church. When not working, he preferred the quiet of his farm near Brantford and the company of his wife and family. Waterous never recovered from the death of his wife in 1889, and he died three years later.

In noting his death, the Toronto Globe praised Charles H. Waterous: “He was the friend of journeyman and apprentice alike and considered their comfort and contentedness as necessary to his own happiness.” Like many other self-made men, Waterous had a concern for his employees that was paternalistic and stopped short of union recognition, as it did, for example, during the strike against his plant in 1872 over the “nine hour” movement. His success, despite numerous setbacks and even failure, demonstrated, to both himself and others unsympathetic to the demands of labour, the efficacy of individual effort.

AO, MU 3307–8, esp. MU 3307, C. H. W[aterous], “Autobiographical sketch” (typescript). Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 13: 24, 55–57, 83, 108. Brant County Museum (Brantford, Ont.), Waterous papers. Brant County Surrogate Court (Brantford), Reg., liber G (1892–93), no.1513 (mfm. at AO). MTRL, T. S. Shenston papers, letter-book, 388–89. NA, RG 31, C 1, 1851, 1861, 1871, Brantford; 1861, 1871, Brantford Township. Private arch., Richard Waterous (Brantford), Family papers. In memoriam: Charles H. Waterous, Jr. (Brantford, 1892). The Waterous’ Engine Works Co.’s (Limited) illustrated catalogue of steam engines, saw and grist mill machinery, Waterous’ improved system of fire protection and water supply, saws and saw mill furnishings (Brantford, 1875; photocopy in AO, MU 3307). Expositor (Brantford), 14 Dec. 1888; 12, 19 Feb., 18 March 1892. Globe, 12 Feb. 1892. Canadian album (Cochrane and Hopkins). D. G. Burley, “The businessmen of Brantford, Ontario: self-employment in a mid-nineteenth century town” (phd thesis, McMaster Univ., Hamilton, Ont., 1983), 98–102, 138, 140–43, 146, 151.

Cite This Article

David G. Burley, “WATEROUS (Waterhouse), CHARLES HORATIO,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/waterous_charles_horatio_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/waterous_charles_horatio_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | David G. Burley |

| Title of Article: | WATEROUS (Waterhouse), CHARLES HORATIO |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |