Source: Link

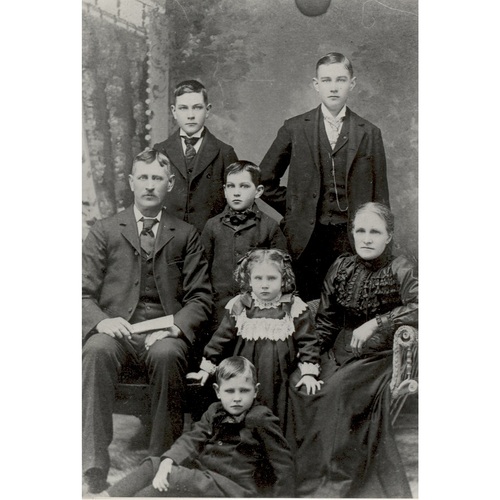

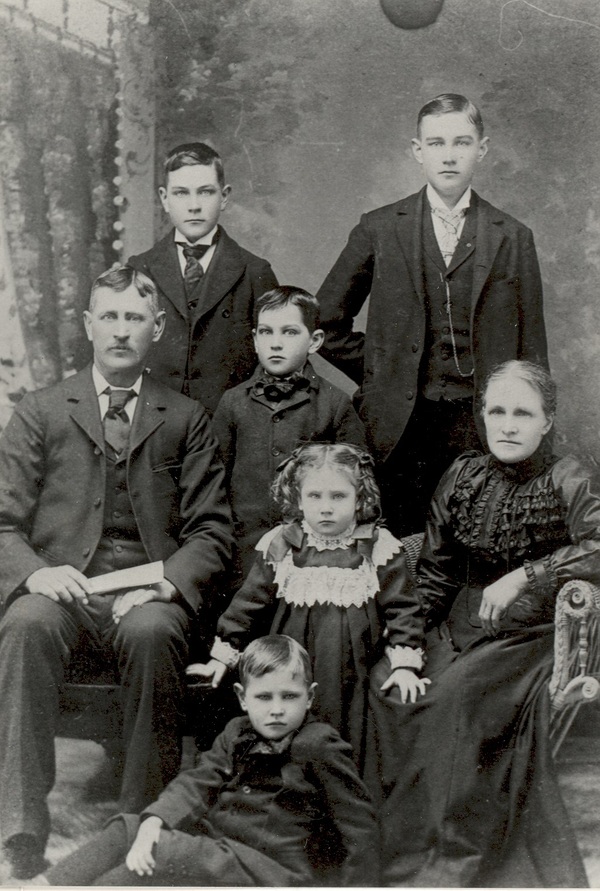

TRASK, CATHERINE (Brown), farmer and home-maker; b. 9 Feb. 1857 in Pilkington Township, Upper Canada, daughter of Charles Trask and Ann French; m. there 9 Jan. 1881 William Brown; d. 26 May 1925 in Peel Township, Ont.

Catherine Trask’s parents were English immigrants who settled as tenants in the Pilkington block, northeast of Guelph [see Robert Pilkington*]. One of seven children, she was left fatherless at the age of seven when Charles Trask died of appendicitis. In 1865 the children received title to the family farm. Catherine continued to live with her mother, and at age 23 she married William Brown, a Methodist farmer from neighbouring Peel Township. They settled initially in the hamlet of Alma, where William found work in a sawmill. Their first son arrived in 1882, a daughter born the following year died after six months, and a second son was born in 1884. When Catherine became pregnant again two years later, the couple took steps to increase their income.

The value of farmland in many counties in Ontario had started to decline after 1879, but there was still a strong demand for grain threshers, whose work was being altered considerably by the use of movable steam engines. Fascinated with mechanics, William Brown bought a 12-horsepower engine made in Elora. By 1887 he had saved enough money to purchase, in Catherine’s name, a 56-acre farm. The following year, when he acquired a better machine, a Champion from the Waterous Engine Works in Brantford [see Charles Horatio Waterous*], William sold his possessions to Catherine, subject to a chattel mortgage provided by flax miller John McGowan. Thereafter all of their property would remain in her name, partially as a hedge against legal liability and perhaps because her family had assisted with the finances. Their dealings in the late 1880s marked the beginning of a complicated series of mortgages and debts that continued throughout Catherine’s married life. Initially these were contracted locally, but later the couple gained credit from the Metropolitan Bank in Guelph and, through Guelph lawyer Walter Ellis Buckingham, the British Mortgage and Loan Company.

While William was threshing throughout the region, from late summer to the dead of winter, Catherine assumed responsibility for running their own farm, though she disdained the work. Since farm accidents were common, particularly those involving exposed machinery, in 1891 the Browns bought insurance from the Alma court of the Canadian Order of Foresters so that Catherine would receive $1,000 if William were killed. (In a work-related accident, he did lose an eye.) Catherine’s early years of marriage were trying in other ways. A third son had died months after she moved to the farm, though two more sons and a daughter would live to maturity. Her first-born shouldered some of the farm work, but he died in 1900. Shortly thereafter the next eldest son, Melvin, moved to the Canadian west in search of cheap land. William’s threshing nevertheless paid enough for the couple to add a kitchen to the back of their storey-and-a-half house. By 1906 they were sufficiently well off to subscribe to the local county historical atlas, where their biographical entry boasted of Liberal and Methodist connections and described William as “one of the best threshers in his section.” It was Catherine who found comfort in her faith – William was never a regular churchgoer.

On small and middling Ontario farms, children were expected to make a contribution through their labour, but allowance had to be made for differences. No sooner had Melvin Brown returned than his brother Ezra, who had shown an aptitude for mechanics, departed for the west too, and Melvin, whose constitution was not strong, left again to work for a manufacturer. Their departures increased the burden on the youngest son, Cecil, and on daughter Dinah. Cecil’s disdain for work and his physical weakness so worried his parents that they bought sickness and funeral insurance for him in 1914. Dinah, who picked up the slack on the farm, wanted to join her father in threshing, but he encouraged her to stay home and learn to plough; she demurred and eventually moved to Elora and then to Hamilton as a servant.

Catherine and William had added to their landholdings in 1909 by purchasing a 100-acre farm nearby. This expansion placed them well above the Ontario mean, but refinancing required a much larger mortgage; new threshing equipment was also purchased on credit the following year. Deciding to leave a business where costs were rising appreciably, William, who at various times had sought employment with implement firms in Waterloo and Hamilton and with Canada Flax and Fibre in Alma, applied in 1914 for the caretaking position at the county court-house in Guelph, but he did not get the job. During World War I inflation hit so severely that the Browns were sometimes unable to pay their grocery bills.

Family circumstances had improved sufficiently by 1919 to allow them to clear the debt on their original farm, but their second property remained encumbered. When Catherine died in 1925 without a will, William became the administrator of her estate. Too old to run the first farm, he turned it over to Cecil, who lacked the ability to make it profitable, and it was sold at auction in 1930. Until his death in 1946, William spent part of each year with Ezra in the west and the remainder with relatives in Ontario.

Catherine Brown’s life reveals the heavy labour that farm women undertook in addition to housework and rearing children. Inextricably bound to the life and career of her husband, she testifies to the importance of family and to the resiliency of farmers in a period of economic and technological change in Ontario. Willing to take risks through the assumption of debt and to engage in various occupations, Catherine and William Brown worked as a couple to improve the chances they had inherited.

[Family information was kindly supplied to the author in his 1993 interviews with Dinah [Brown] Cripps of Kitchener, Ont., and with Irene [Brown] Allan, Milton and Morley Trask, and Enid Whale, all of Alma, Ont. Additional details were provided by copies of family bible records in the possession of Milton Trask. t.c.].

AO, RG 80-5-0-103, no.12137. Elora Municipal Cemetery (Elora, Ont.), Records. NA, RG 31, C1, 1871, Pilkington Township, Ont., div.1: 22; 1881, Peel Township, Ont., div.2: 44. Univ. of Guelph Library, Arch. and Special Coll. (Guelph, Ont.), Wellington North Land Registry copy-books, Peel Township: 297–98, 703; XR1 MS A060 (Henry Wissler papers), box 1 (d). Wellington South Land Registry Office (Guelph), Deeds, instrument nos.Y27-11616, Y28-11640, Y34-16409, Y35-16411; Pilkington Township, abstract index to deeds, concession 1, lot 3; reg. of deeds, book 3, no.24401 (27 July 1865) (mfm. at AO). Historical atlas of the county of Wellington, Ontario (Toronto, 1906; repr. as Illustrated historical atlas of Wellington County, Ontario, Belleville, Ont., 1972). Threshermen’s Rev. (Detroit and St Joseph, Mich.), April, June 1911.

Cite This Article

Terry Crowley, “TRASK, CATHERINE (Brown),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/trask_catherine_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/trask_catherine_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Terry Crowley |

| Title of Article: | TRASK, CATHERINE (Brown) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |