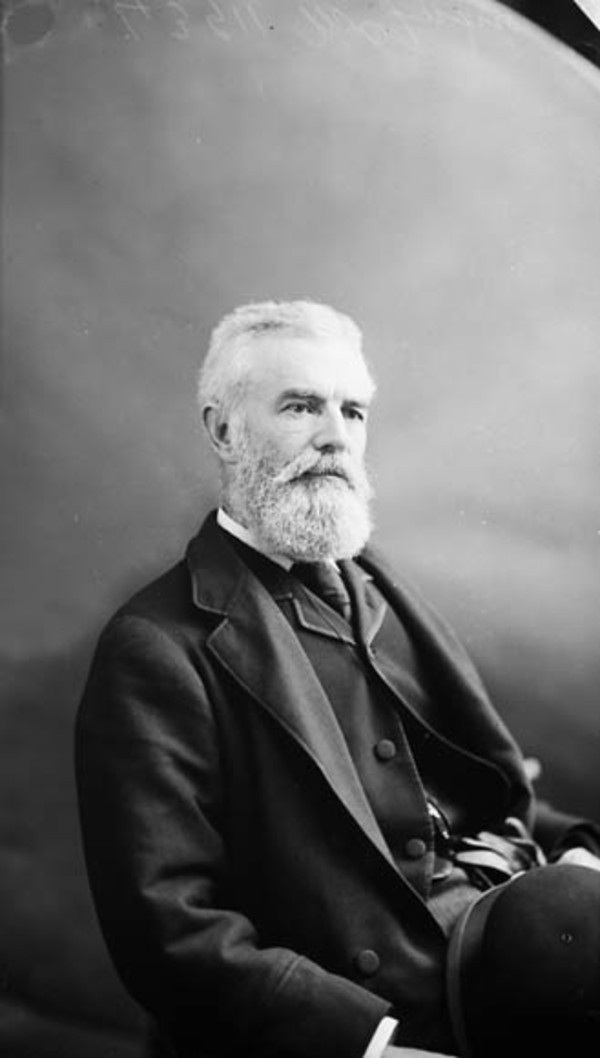

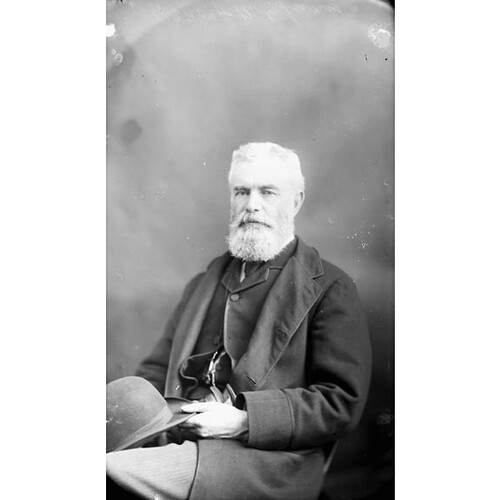

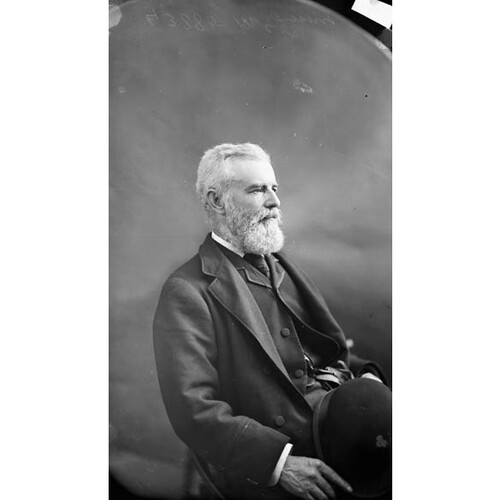

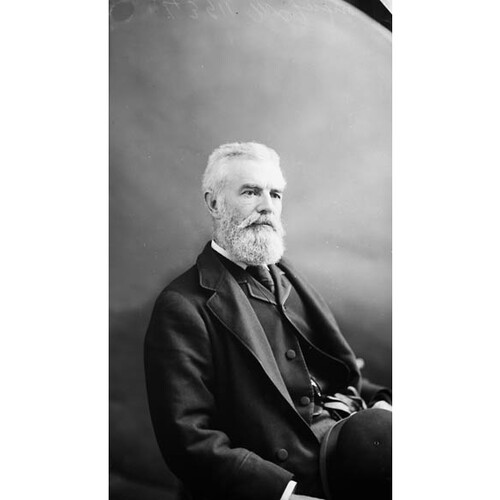

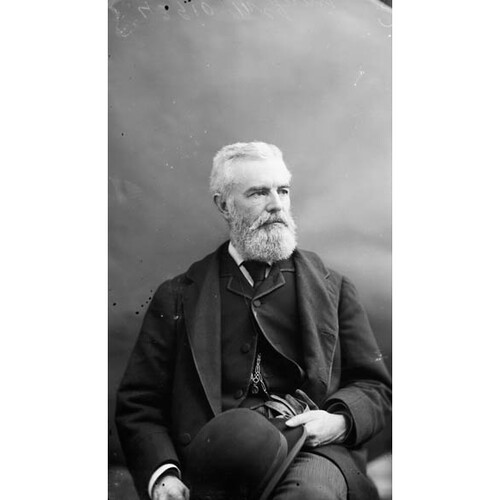

McINNES (MacInnes), DONALD, businessman and politician; b. 26 May 1824, 15 Oct. 1824, or 1826 in Oban, Scotland, son of Duncan McInnes, grazier, and Johanna Stuart; m. 30 April 1863 Mary Amelia Robinson, and they had five sons and a daughter; d. 1 Dec. 1900 in Clifton Springs, N.Y., and was buried in Hamilton, Ont.

Donald McInnes’s family emigrated to Upper Canada in 1840 and settled at the head of Lake Ontario on a 200-acre farm in Beverly Township, which the father worked until his death in 1852. By that point Donald, who had begun his business career in Dundas, was already well established in Hamilton under the style of D. McInnes and Company, manufacturers’ agents and dry-goods wholesalers. McInnes had started that firm in partnership, perhaps with Guy R. Prentiss, a New York capitalist, but came to carry it in partnership with his brothers, Hugh and Alexander. At various times Donald also undertook partnerships with John Calder of Hamilton. Initially McInnes imported largely from New York, where he did much buying in person, sometimes under direct instructions from retailers, sometimes even, in his early years, for individual retail purchasers. Increasingly he imported from England via Montreal. This route gave him access to some superior cotton prints and let him establish important links in the Montreal business community. When possible he liked to purchase supplies domestically, as his buying from a Niagara region cotton-mill in the 1860s made apparent. There is evidence that he attempted to export Canadian-made clothing to Britain, though without success.

Along with Isaac Buchanan*, McInnes represented the Hamilton Board of Trade at the American boards of trade convention in Detroit in 1865, a clear indication of his stature in the Hamilton business community. McInnes and Company was reputed to be the largest dry-goods wholesaler west of Toronto by the early 1870s. It certainly was a massive concern: even in July 1879, in the midst of depression, when the business had undoubtedly shrunk from its highest levels, total stock on hand in its Hamilton warehouse was valued in the Monetary Times at approximately $250,000.

An ambitious man, McInnes sought a degree of vertical integration in his operations. He financed his brother Alexander in forming a partnership with William Eli Sanford to open a clothing manufactory in Hamilton in 1861. Though highly successful, the partnership was dissolved in 1871, by which point Donald McInnes was already spreading his investments into textile manufacturing. In 1867 McInnes, together with George Stephen* and Warwick M. Hopkins of Montreal, John Proctor of Hamilton, and John Warwick of Speedsville, a small woollen centre in Wellington County, had established the Cornwall Manufacturing Company; its woollen mill was rebuilt in 1871. Early the following year, with Stephen, Bennett Rosamond*, Donald Alexander Smith*, and others, McInnes took a large stock position in the Canada Cotton Manufacturing Company of Cornwall, which they formed to compete against the Stormont Cotton Manufacturing Company of Andrew Frederick Gault* and Robert Leslie Gault of Montreal. Since they paid no duty on raw cotton and imports of finished cottons were subject to a 15 per cent tariff from 1867, McInnes and other manufacturers could hope to make substantial profits in a protected, domestic market. McInnes was president and managing director of Canada Cotton for several years. For a time its plant was the largest in Canada, with 20,000 spindles and 350 employees, even in the depression years of the 1870s. The company expanded in 1882, when more than 200 employees were added. In the 1880s McInnes tried to have some of the Cornwall-produced cottons printed in England to broaden his market.

As a wholesaler McInnes was vitally interested in the process of distribution, and so he had a stake in the expansion of transportation facilities in southwestern Ontario. He invested in the Great Western Railway, one of Hamilton’s efforts to express its commercial hegemony over this region. He rose to be a director and a vice-president of the Great Western. His purchase in 1872 of Dundurn Park, the former home of Hamilton’s first great railway politician, Sir Allan Napier MacNab*, was symbolic of McInnes’s growing interest in railways as well as his position in the community. His involvement in the politics of railways was extensive. In 1872 he became a provisional director of the Canada Pacific Railway Company. He was briefly in the running to head a syndicate for the construction of the Pacific railway in 1880 and from 1888 he was a director of the Canadian Pacific Railway. He used his political influence to gain support for his South Saskatchewan Valley Railway Company, incorporated in 1880.

Like businessmen elsewhere, McInnes grasped the importance of local banking establishments to expedite commerce. Given Hamilton’s growth and its function as a wholesaling entrepôt for southwestern Ontario, the weakness and then the amalgamation of the Gore Bank with the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 1870 made the establishment of another local bank imperative. McInnes was the key figure in pushing for such a bank, the Bank of Hamilton, and he served as its first president (1872–81) . He was thus assured of adequate credit facilities for his various enterprises. As well, he had investments in the Hamilton-based Canada Life Assurance Company, of which he was a director.

For a man of great wealth, prestige, and power, McInnes would leave a relatively small estate, worth about $82,000. It is evident that through the depression of 1874–79 and later he suffered significant business reverses. The Great Western was not enormously profitable, necessary though it was in his wholesaling activities. His efforts to establish lines of integration in his dry-goods business, by heavy investment in the cotton company at Cornwall, ran into difficulties in the depression. The plant suffered from severe flooding in 1887. Nor was it spared labour troubles. A minor strike in 1883 was followed by major ones, especially that of 1888, when, organized by the Knights of Labor [see Daniel John O’Donoghue*], the workers protested potential wage cuts. Although the strike did not last long, it was bitter and McInnes, wisely for such a resolute man, chose to compromise on the wage issue and not to prosecute arrested strikers. None the less, another strike followed in 1889. The attempt to cut wages in 1888 reflected competitive conditions. The company had done well during the boom of the early 1880s, but when it broke in 1883 the firm faced relentless rivalry in the domestic market. Not surprisingly, McInnes was a whole-hearted supporter of cartel arrangements in the cotton-textile industry, and in 1883 he became the president of the Cotton Manufacturers’ Association, which aimed at fixing prices and production.

McInnes’s sizeable investment in the Canada Iron and Steel Company at Londonderry, N.S., in which he was associated with Scottish capitalists and such Montreal investors as Hugh Allan* (until 1874), Alexander Thomas Paterson, George Stephen, and J. Greenshields, also did not provide large returns; indeed, he undoubtedly lost money in that enterprise. Access to raw materials and markets was not optimal for the Londonderry firm, there were serious labour problems, and production techniques were, perhaps, excessively experimental. The company folded in 1883, after incurring considerable losses. Nor did McInnes’s South Saskatchewan Valley Railway Company prove to be a money-maker.

Most devastating of all, McInnes’s commercial base – his enterprises in importing and wholesale distributing – suffered erosion and severe loss. Channels of distribution were changing and Hamilton’s position as a major entrepôt for southwestern Ontario was in decline. Twice in the 1870s McInnes was rumoured to be moving his operations to Toronto. His diversification of investment was undoubtedly a result of these pressures. The volatility in the geography of business was compounded by the severity of the depression of the 1870s. Because his wholesale operations required him to extend a great deal of credit to those below him in the distribution chain, he was badly exposed in the harsh economic downturn. In 1894 he would claim that the federal Insolvent Act of 1875 had made it easy for some of his debtors to escape their obligations and that he had “suffered very severely from it.” Nor was he spared acts of God. One partnership in which he was involved, McInnes and Calder, suffered losses from fire in 1870. An innovative auction which involved heavy advertising, three days of auctioning, and such enticements as no reserve bids, credit arrangements for retail bidders, free luncheons, and a round of drinks for toasts for some 300 bidders, permitted substantial recovery. The crippling blow was the destruction by fire of his huge Hamilton warehouse and offices on 1 Aug. 1879. The magnificent warehouse, insured for $86,000, and the stock, worth an estimated $100,000 more than the insurance of $159,000, were completely destroyed. McInnes and Company, already over-extended because of the depression, compromised with its creditors at a meeting in Montreal, agreeing to pay forty-five cents cash on each dollar of debt. McInnes continued in the wholesale business only until 1882.

In person McInnes was articulate, charming, and well read. He esteemed elegant surroundings, witness his substantial renovations at Dundurn, his presidency of the Hamilton Golf Club in 1897, and his attendance at the Hamilton Club, the Toronto Club, the Manitoba Club in Winnipeg, the Rideau Club in Ottawa, the St James Club in Montreal, and the Conservative party’s United Empire Club in Toronto. He was no stranger to the politics of social status, as the purchase of Dundurn Park and his entertainment of notables, including Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell*] made evident. His early captaincy in the militia showed his strong sense of social place, despite his resignation in 1863. McInnes’s powerful attachment to Great Britain was expressed during visits to England and Scotland necessitated by business, in his subscription to Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, and in his insistence that each of his sons receive some education in Britain. McInnes waited until he was well established before he married Mary Amelia Robinson in 1863, at St James’ Cathedral (Anglican) in Toronto. She was the fourth daughter of the late Sir John Beverley Robinson*, a former chief justice. Though McInnes may have been a Presbyterian early in life, he became a practising Anglican. His wife died in 1879. By 1883, for reasons that are unknown, he had changed the spelling of his name to MacInnes.

McInnes had a sharply defined sense of personal, group, and class interest, which found expression in his political activities. He had a startlingly clear conception of confederation as a device through which a larger domestic market could be created, and even before it occurred he was testing out the Maritimes. Certainly by 1866 he felt the larger market should have vigorous tariff protection. After 1867 his attachment to Sir John A. Macdonald and the Conservative party was unmistakable. In the election of 1872 Sir John requested him to stand in Hamilton, pointing out that the reduction in federal revenues as a result of the elimination of duties on tea and coffee, and the contemplated expenditures on a transcontinental railway, would make higher tariffs inevitable. Although he did not run, McInnes used his prestige and authority to bring voters and money to the Conservatives in that election. By 1873 Macdonald already considered him an excellent prospect for a senatorship.

McInnes’s relationship with Macdonald was cemented during the mid 1870s, when the Hamiltonian was an important figure in persuading the Conservative leader of the centrality of tariff protection. Giving a pointed and personal example of the damage being done in Canada by international competition during the depression, McInnes impetuously wrote to Macdonald in 1877 that the cotton industry was “starving . . . & cant make both ends meet. Market market is the great cry.” American dumping of cottons was destroying that market, he claimed. Certainly the rapid and uneven decline of cloth prices in a context of fierce domestic and international competition meant that even the duties imposed in 1874 by the government of Alexander Mackenzie, 10 per cent on cotton thread and 17½ per cent on finished cotton, provided little protection for Canadian manufacturers in their production of undyed, unprinted cotton. In the campaign leading to the election of 1878, which would end the Liberals’ spell in power, McInnes worked tirelessly in both Cornwall and Hamilton to ensure Conservative victories. He organized for the protectionist Dominion National League (the unacknowledged offspring of the Conservative party and the Ontario Manufacturers’ Association), provided funds for various local party organizations, and stooped to sway individual voters through techniques that were virtually coercive. (The election of Darby Bergin in Cornwall was controverted in 1879 because of the “corrupt practices” used on his behalf.) McInnes threw his influence as well into the debate among businessmen. He was vice-president of the highly protectionist Ontario Manufacturers’ Association and he frequently spoke in public to persuade businessmen of the necessity for protection. He received a partial reward in the tariff of 1879, which set high duties on cotton goods, though he worried that Samuel Leonard Tilley, the finance minister, had insufficient protectionist backbone. Further rewards followed: in 1880 he obtained the chairmanship of the royal commission on the organization of the civil service and on 24 Dec. 1881 he was granted the senatorship he had coveted.

In a letter to Macdonald in 1879 McInnes claimed that manufacturers should not “act in a warm selfish spirit for the sake of personal gain. Speaking for me at least I disdain it in toto.” His business activity at the time of the making of the 1879 tariff, and his involvement with the South Saskatchewan Valley Railway Company in the 1880s, shows McInnes’s confusion of his own “warm selfish spirit” with industrial patriotism. Satisfied with the tariff on cotton, he made his chief concern in 1879 the duty on pig-iron. He found the $2-per-ton level inadequate to allow for profitable manufacture at the Londonderry iron- and steel-works; indeed, he outlined to Macdonald in stark detail the heavy losses the Londonderry works was enduring. When the pressure of founders and secondary iron manufacturers made a higher duty on iron unlikely, he pursued government support by other means. From Charles Tupper*, minister of public works, McInnes requested subsidization by the government-controlled Intercolonial Railway for the carriage of iron from Nova Scotia to the central Canadian marketplace. In following years he continued to seek higher iron tariffs while large industrial consumers lobbied for the reverse, among them Hart Almerrin Massey, who at the same time wanted higher tariffs to protect his agricultural implements – just as McInnes did for his cotton.

As president of the South Saskatchewan Valley Railway Company, McInnes similarly indulged in endless special pleading with Macdonald and others on its behalf. Pleas for higher than normal freight rates for the proposed line were piled on top of entreaties for special considerations in land grants to the company. These entreaties followed on arrangements for work on a government-financed railway by a construction company with which McInnes was associated. The Hamilton financier was typical of businessmen in the late 19th century who used private relationships to foster personal or group interests.

The South Saskatchewan Valley Railway was both symbol and means of Senator McInnes’s growing fascination with the Canadian west. He was enthralled by the massive profits George Stephen and his colleagues garnered on the first Prairie sections of the CPR during the boom of the early 1880s. His railway, designed to be a feeder to the CPR, might have enjoyed similar profitability, but it was never built: by about 1883 it had been outmanœuvred by a railway controlled by the Allan interests of Montreal, the Manitoba and North Western. Travelling in the South Saskatchewan region, McInnes became an advocate of its geographic splendours and for the grievances of its settlers, transmitting to Macdonald their concern over railway monopoly and their need for sawmills, more railways, better postal service, and land agents who clearly understood land regulations. There is little correspondence to record the disappointment he must have felt at witnessing the paucity of settlers in the region during most of the 1880s. McInnes was blind, however, to the range of social and political dynamics in the west. He failed to comprehend the western roots of the North-West rebellion of 1885 [see Louis Riel*], for example, seeing it purely as an issue of Quebec-based French nationalism, which he thought should be stamped out.

McInnes’s career as senator, while not notable, was fairly busy. Until Macdonald’s death in 1891 McInnes was active as a Conservative organizer and fundraiser. In the first years after his appointment in 1881 he participated little in the debates and legislative operations of the Senate, but later he was constantly occupied forwarding bills of incorporation, especially of railways. He saved most of his oratorical fire for his advocacy of civil service reform, though occasionally he spoke at length on trade and tariff matters, on the development of the west, and on proposed insolvency legislation. The recommendations in 1881 of the royal commission on the civil service, which he had chaired, stressed the necessity of reorganizing the public service internally and professionalizing it on the British model: competitive entrance examinations, promotion based on merit, and a watch-dog civil service commission. The Civil Service Act of 1882, as McInnes proclaimed at length in 1891 and again in 1895, did not meet the strictures of those recommendations, though he was willing to take credit for the act’s best features. The senator’s last lengthy speech, in 1895, was on the necessity for further reform of the civil service. He spoke relatively little after that and his participation declined abruptly after 1898.

In the 1890s McInnes became less active in business and political life, as the generation of men with whom he had extensive contacts died or retired. A stroke left him partially paralysed and he moved to Toronto, probably to be close to one of his sons. In delicate health, he consolidated his estate, selling Dundurn Park to the city of Hamilton in 1899 for a reputed $50,000, and he sought rest-cures. It was in the midst of one of these, at Clifton Springs, that he died, on 1 Dec. 1900. His burial service was held at All Saints’ Church (Anglican) in Hamilton.

AO, RG 22, ser.205, no.5112; RG 55, partnership records, Wentworth County, copy-book, no.12; declarations, nos.222, 625, 864, 875–76. Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 25: 225 (mfm. at NA). HPL, Arch. file, Brown–Hendrie papers, reminiscences of Adam Brown, 10–11; Scrapbooks, H. F. Gardiner, 218: 58–59. NA, MG 24, D16: 23183; MG 26, A; RG 16, A1. Can., House of Commons, Journals, 1876, app.3: 142; Senate, Debates, 7 March 1889; 5 March, 18 April 1890; 20 Aug. 1891; 17 April 1894; 29 May, 15 July 1895. HBRS, 31 (Bowsfield). Ontario Manufacturers’ Assoc., Report of proc. of annual meeting (Toronto), 1877: 3. Hamilton Spectator, 1 Dec. 1900. Monetary Times, 8–22 Aug. 1879; 31 Aug.–14 Sept., 12 Oct. 1883. CPC, 1883–85, 1887. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. DHB. [J. J.] B. Forster, A conjunction of interests: business, politics, and tariffs, 1825–1879 (Toronto, 1986); “Finding the right size: markets and competition in mid- and late nineteenth-century Ontario,” Patterns of the past: interpreting Ontario’s history . . . , ed. Roger Hall et al. (Toronto and Oxford, 1988), 150–73. Elinor Kyte Senior, From royal township to industrial city: Cornwall, 1784–1984 (Belleville, Ont., 1983), 228.

Cite This Article

Ben Forster, “McINNES (MacInnes), DONALD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcinnes_donald_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcinnes_donald_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ben Forster |

| Title of Article: | McINNES (MacInnes), DONALD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |