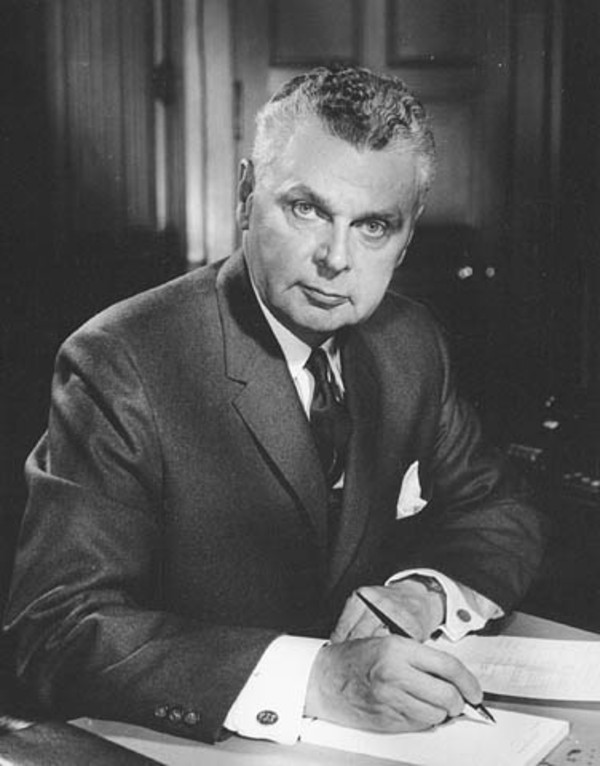

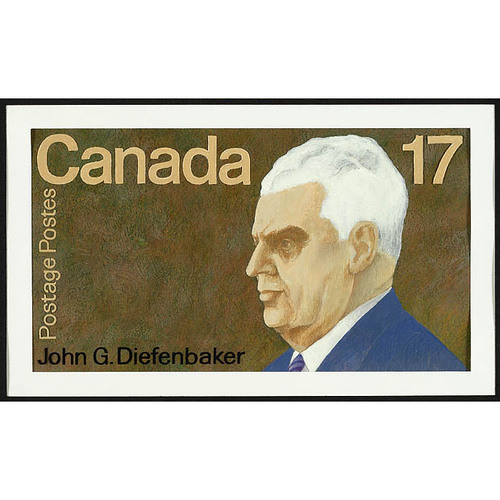

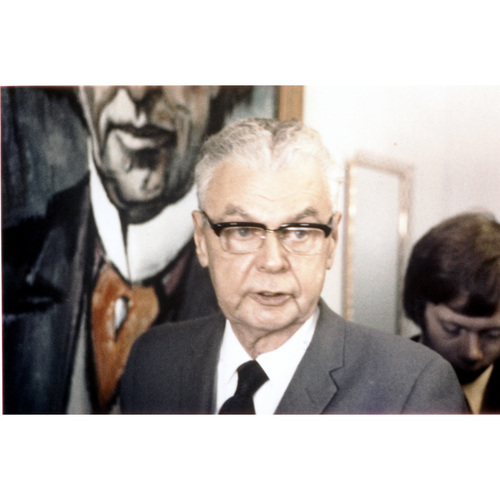

DIEFENBAKER, JOHN GEORGE, lawyer and politician; b. 18 Sept. 1895 in Neustadt, Ont., elder son of William Thomas Diefenbaker and Mary Florence Bannerman; m. first 29 June 1929 Edna Mae Brower (d. 1951) in Toronto; m. there secondly 8 Dec. 1953 Olive Evangeline Palmer, née Freeman (d. 1976); no children were born of either marriage; d. 16 Aug. 1979 in Ottawa.

In his memoirs John Diefenbaker describes his ancestors as “dispossessed Scottish Highlanders and discontented Palatine Germans.” His paternal grandfather, George M. Diefenbacker (Diefenbach or Diefenbacher), was born in the Grand Duchy of Baden (Germany). In the 1850s he immigrated to Upper Canada, where he married and worked as a wagon maker. His son William, one of seven children, was born in April 1868, attended school in Hawkesville and Berlin (Kitchener), Ont., and received a teaching certification from the Model School in Ottawa in 1891. In May 1894 he married Mary Bannerman, whose grandparents had lost their Scottish tenancies during the land clearances of 1811-12 in Sutherland. They had been members of the third party of immigrants that Lord Selkirk [Douglas*] brought to the Red River settlement (Man.), arriving via Hudson Bay in June 1814. After one harsh winter they travelled by canoe brigade to Upper Canada and finally settled in what would become Bruce County, where their granddaughter Mary was born in 1872.

William and Mary Diefenbaker were living an itinerant life when their first son, John, was born in 1895. A brother, Elmer Clive, arrived in 1897. During John’s early years, the family followed William from one low-paying teaching job to another, first in Neustadt, then in Greenwood, then in Todmorden. Young John began his schooling at age four in his father’s classroom. In 1903, suffering from debt and ill health, William sought a teaching post in the North-West Territories and was offered work in the Tiefengrund Public School District near the site of Fort Carlton (Sask.), halfway on the wagon route between Winnipeg and Edmonton. For two winters the Diefenbakers lived in primitive quarters attached to the rural schoolroom, supplementing their income with gifts of vegetables, sausages, and firewood from their farming neighbours. In December 1904, on payment of a $10 registration fee, William took possession of a quarter-section homestead in nearby Borden, but a lack of capital prevented him from occupying the land until the summer of 1906. In the interim, the family moved once more, to Hague for the winter of 1905-6, where William taught school and served as village secretary.

In the summer of 1906 the Diefenbakers took up their property, built a three-room frame house, a barn, and a shack, planted a garden, broke ten acres of grassland for crops, and welcomed William’s bachelor brother Edward Lackner to a neighbouring homestead. The two brothers found teaching jobs at local one-room schools – William at Hoffnungsfeld and Edward at Halcyonia – and that autumn John entered grade 7 at his uncle’s school. For three harsh winters the family survived on the homestead, but in 1910, after satisfying the minimal residence requirement for full title to the land, the Diefenbakers departed for Saskatoon, where William found work as a clerk in the provincial public service. In 1911 he became an inspector in the customs office, where he remained until his retirement in 1937.

John attended the Saskatoon Collegiate Institute for two years. With his mother’s encouragement he entered the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon in the autumn of 1912 to study arts and law. His early university record was undistinguished. He already had a political career in mind; in later years his family recalled that his ambition to be prime minister had been expressed before he was ten. In the spring of 1914 he took up a contract teaching primary school in the Wheat Heart Public School District. In October, after teaching for five months of the seven-month contract, he made an unusual arrangement to delegate completion of the school term to his uncle Edward in order to return to university. Subsequently Diefenbaker sought payment of what he claimed was a deficiency in his salary, a claim rejected by the school board and the Department of Education.

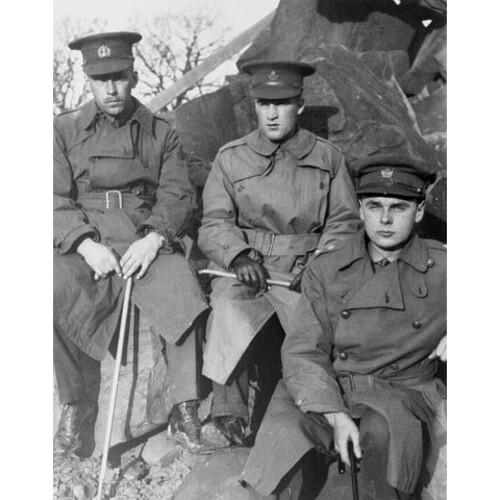

In the spring of 1915 Diefenbaker received his ba and that autumn he returned to university for an ma in political science and economics. Meanwhile, World War I had become a contest of steady slaughter on the Western Front. In March 1916 he enlisted for officers’ training and was commissioned a lieutenant in the infantry. He received his ma in absentia and, after a month of lectures and drill, he undertook three months of articling in a Saskatoon law office before requesting an overseas posting in August. He sailed for England in September as a member of the 196th (Western Universities) Battalion and spent the autumn at camps in Shorncliffe and Crowborough. After a few months he was found medically unfit for service at the front and in February 1917 he returned to Canada. He was demobilized in December and denied a pension sought on grounds of disability. The military records and his own account of this episode are contradictory and were never reconciled during his lifetime; the official records suggest that he was judged unfit because of “general weakness” without demonstration of any physical disability, while he claimed to have been injured by a falling pickaxe. During the 1920s he showed gastric symptoms consistent with a possible diagnosis of psychosomatic illness in 1916-17. Similar cases of neurasthenia, more or less intense, would be common in both world wars.

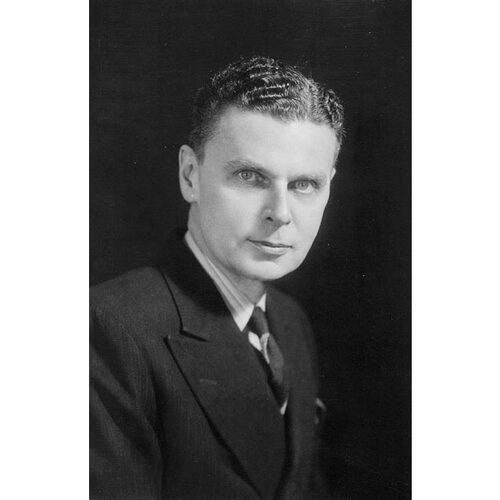

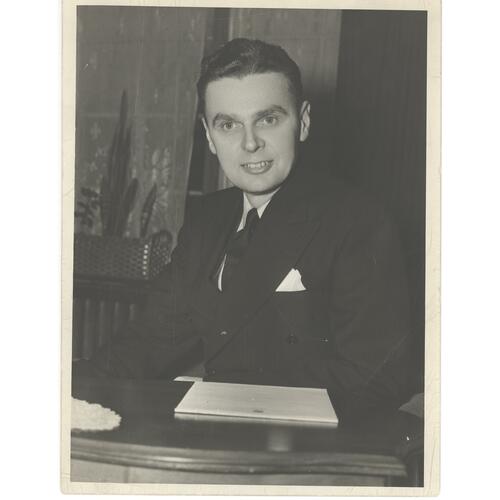

After returning to Saskatoon, Diefenbaker articled in three law firms during 1918-19 and attended classes in law at the university. He received one year’s credit in law school for his undergraduate courses in law and an additional year’s credit as a veteran. In May 1919 he obtained his llb. At his request, the Law Society of Saskatchewan granted him two years’ exemption from articling and in June 1919 he was called to the bar. He opened his first office in Wakaw, 40 miles north of Saskatoon. Wakaw was a thriving market town of 400 in a farming district settled by immigrants from central and eastern Europe. It was on the district court circuit and had easy access by rail and road to high court sessions in Saskatoon, Prince Albert, and Humboldt. The tall, thin young man with deep blue eyes and wavy black hair, dressed soberly in a dark three-piece suit, made an immediate and striking impression in the small town.

Diefenbaker’s first court case involved the defence of a client accused of careless wounding with a rifle. The assailant had immediately offered first aid and turned himself in to the police. Diefenbaker argued successfully in October 1919 that the shooting was an error committed in the fading evening light. He was soon busy with other cases and within a year he was able to move to larger offices and buy a Maxwell touring car. In the fall of 1920 he was elected to the Wakaw village council for a three-year term. In his first widely noticed case, he acted on appeal for clients from the French-speaking community in the Ethier Public School District, defending two school trustees against a charge that they had violated the province’s School Act by permitting teaching in French. Although the court found that the act had indeed been violated, he won the appeal in May 1922 on the technical ground that trustees could not be held responsible for the internal operations of the school. He became known as a defender of minorities and his legal fees in the case were paid by the Association Catholique Franco-Canadienne de la Saskatchewan.

Although Diefenbaker’s civil case list grew, his reputation would be founded on his record as a criminal defence lawyer. In the courtroom he discovered and honed his dramatic genius. He mastered juries with his powerful and edgy voice, his penetrating stare, his waving arm and accusatory finger, his ridicule and sarcasm, and his command of evidence and the law. He identified naturally with the dispossessed and the poor, with all those who lacked the wealth, power, and confidence of the British Canadian mainstream; and he argued his cases with passion. Saskatchewan was fertile ground for these talents. In 1924 he took on a partner, Alexander Ehman, in his Wakaw office and moved his own practice to Prince Albert. Two other partners succeeded Ehman before Diefenbaker closed the Wakaw branch in 1929.

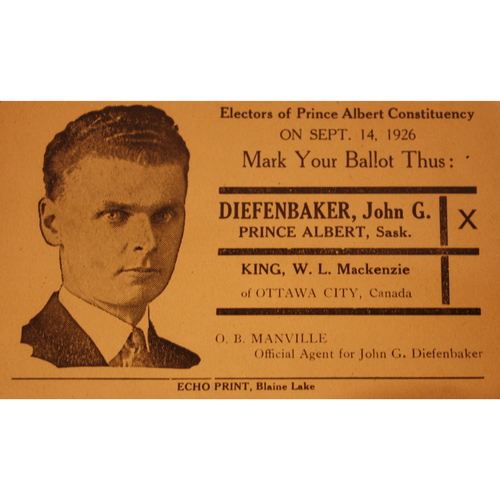

The young lawyer’s father had been a supporter of Liberal prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*. As a repatriated soldier, Diefenbaker had supported the Union government of Sir Robert Laird Borden* in the election of 1917, although he was opposed to the War-time Elections Act, which deprived recently naturalized Canadians of the vote. In 1921 his political affiliation was uncertain. He admired Andrew Knox, the mp for Prince Albert who had successfully shifted his candidacy from the Unionists to the Progressive Party, but he kept his own political views private. He would later say that the Liberal Party, which dominated Saskatchewan politics in the 1920s, hoped to recruit him, but claimed that “I was never keen.” In 1925 his name was proposed and rejected for nomination as a Liberal in the June provincial election, but on 6 August he was acclaimed as the Conservative candidate for Prince Albert in the forthcoming federal election. “I haven’t spent a lifetime with this party,” he would reflect in 1969. “I chose it because of certain basic principles and those . . . were the empire relationship of the time, the monarchy and the preservation of an independent Canada.” But he distrusted the Ontario-centred policies of the party and disagreed publicly with its leader, Arthur Meighen*, who opposed completion of the Hudson Bay Railway and threatened to change the railway freight rates benefiting the movement of the prairie grain crop. On the hustings Diefenbaker campaigned feverishly and responded angrily to the insult that he was a “Hun.” Despite Conservative gains elsewhere in the election of 29 October, the party won no seats in Saskatchewan. In Prince Albert, Diefenbaker ran third and lost his deposit.

The Liberal victor in Prince Albert, Charles McDonald, almost immediately resigned his seat to make way for Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King*, who had lost his own seat in York North. The Conservative Party did not nominate against him, although Diefenbaker privately encouraged the entry of an independent candidate. King won easily. In late June 1926 his government resigned in what became known as the King-Byng affair and was replaced by Meighen’s Conservatives, who were defeated at once in the House of Commons. The house was dissolved for a September election. Diefenbaker stood again in Prince Albert, facing the former prime minister in a two-way contest. Once again he was at odds with his own leader, who opposed King’s recently established old-age pension scheme and maintained his unpopular views on freight rates and the Hudson Bay Railway. King’s Liberal Party was returned to power with an absolute majority, while the Conservatives lost all but one seat in the three prairie provinces.

Despite his electoral losses Diefenbaker was beginning to attract attention elsewhere in the country. When he made his first political journey out of Saskatchewan in 1926 to address a Conservative convention in British Columbia, he was described by the journalist William Bruce Hutchison* as “tall, lean, almost skeletal, his bodily motions jerky and spasmodic, his face pinched and white, his pallor emphasized by metallic black curls and sunken, hypnotic eyes.” Yet from this “frail, wraithlike person,” continued Hutchison, “a voice of vehement power and rude health blared like a trombone.”.

Diefenbaker attended the 1927 federal leadership convention in Winnipeg that chose Calgary millionaire Richard Bedford Bennett* to replace Meighen and became Bennett’s admirer as he rebuilt the national party. In Saskatchewan the Conservatives prepared to confront the entrenched provincial Liberal government, whose strength lay in its good relations with the grain growers’ associations and the large, mostly Catholic, immigrant communities. The Conservatives turned elsewhere for support. From 1926 to 1928 a ragtag Canadian offshoot of the Ku Klux Klan created more than 100 local branches in the province, appealing to anti-Catholic, anti-French, and anti-immigrant sentiments. Although Diefenbaker was never a member, his party was caught up in this bigoted wave of nativism, reflecting or tolerating support for extremist views at its 1928 convention in Saskatoon and during a by-election in Arm River later that year. During the by-election campaign Diefenbaker shared the platform several times with one of the Klan’s promoters, James Fraser Bryant, and at one campaign meeting he challenged Premier James Garfield Gardiner* over the “sectarian influences . . . pervading the entire education system.” The Liberal Party won by a narrow margin, but Conservatives drew the lesson that extreme claims could win votes. They carried their anti-Catholic message into the provincial election of 6 June 1929, emphasizing the issues of race, religion, language, and immigration. Diefenbaker was the Conservative candidate in Prince Albert and was promised the attorney generalship in the event of victory. He lost the contest to the sitting Liberal, Thomas Clayton Davis, but Gardiner’s Liberals were replaced by a Conservative minority government dependent on Progressive support. The Klan soon disappeared from Saskatchewan.

In the summer of 1928 Diefenbaker had become engaged to Edna Brower, a vivacious Saskatoon schoolteacher. They were married three weeks after the provincial election. Edna was an immediate asset to the aspiring politician, offsetting his dour presence with her warmth and spontaneity. She was resented by Diefenbaker’s mother, however, who insisted that she remain first in her son’s affections. John maintained close ties with his parents, making frequent visits to Saskatoon at their call. He also played a protective and dominating role towards his brother, Elmer, who now occupied part of the Diefenbaker law office in Prince Albert as an insurance broker and minor entrepreneur. Edna was closely involved in Diefenbaker’s legal life, watching and commenting on his courtroom behaviour, observing the reactions of judges and juries, and offering support and reassurance to his clients.

In the late 1920s Diefenbaker defended four men on charges of murder. In the first case, The King v. Bourdon in 1927, he appeared as junior counsel, but afterwards always acted as lead. The defendant was found not guilty. The following year, in The King v. Olson, Diefenbaker requested on appeal that a conviction for murder be quashed on the ground that the trial judge had improperly directed the jury. The judgement was sustained, but on the court’s recommendation Diefenbaker petitioned for mercy, claiming that the defendant had been mentally incapable of standing trial. The federal cabinet commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. He was similarly successful in The King v. Pasowesty in having a death sentence commuted to life imprisonment. In The King v. Wysochan he defended his client by arguing that the murder had been committed by the victim’s husband. The defendant was convicted, the appeal was dismissed, the federal cabinet denied a reprieve, and Alex Wysochan was hanged in the Prince Albert jail in June 1930.

During this trial, Diefenbaker suffered a recurrence of his gastric illness and afterwards took leave from his law practice to recuperate. He was not a candidate in the federal election of 28 July 1930 which resulted in a Conservative majority government under Bennett and eight seats for the party in Saskatchewan. As a result of the provincial Conservative victory of 1929, however, he had been named a kc on 1 Jan. 1930. Later in 1930 he served as junior counsel to the provincial royal commission known as the Bryant charges commission, investigating Conservative claims that the previous government had interfered with the operations of the provincial police force for partisan advantage. The commission wound up inconclusively in early 1931.

As the great depression deepened on the prairies into a descending spiral of drought, crop failure, debt, and unemployment, the new provincial government lost its revenues and its sense of direction. Diefenbaker’s law practice in Prince Albert contracted modestly, but he was able to maintain a comfortable income throughout the 1930s. In 1932 his law partner, William G. Elder, departed in conflict, he claimed, over finances and ethics. The following year Diefenbaker recruited John Marcel Cuelenaere as an articling student. Cuelenaere would stay on as his partner until 1957 and, as a Liberal partisan, would later serve as mayor of Prince Albert, an mla, and a provincial cabinet minister.

In October 1933 Diefenbaker was elected vice-president of the Saskatchewan Conservative Party and in November he put himself forward as a last-minute candidate for mayor of Prince Albert on a platform of interest reduction on the civic debt. He lost by only 48 votes in a record poll. Diefenbaker was not a candidate in the June 1934 provincial election, but he campaigned for the Conservatives in a hopeless cause. The party lost all its seats to the Liberals under Gardiner, who faced a small Farmer-Labour opposition.

Meanwhile, Diefenbaker continued to admire Bennett’s leadership. After the prime minister announced his New Deal in January 1935, Diefenbaker wrote that Bennett’s radical proposals “have given our rank and file something to enthuse over – a new hope and a new spirit.” But the federal government was divided and demoralized by the continuing depression. In July 1935 Diefenbaker turned down an offer of the federal nomination in Prince Albert. He campaigned for the party during the October election, only to see its prospects shattered once more in a national Liberal landslide. In Saskatchewan the Conservatives elected only one member in the province’s 21 seats. Bennett led the opposition for another three years while King returned to the prime ministership.

After its electoral defeat in 1934, the Saskatchewan Conservative Party had led a ghostly existence with no more than a handful of activists. In August 1935 Diefenbaker inherited the post of acting president of the provincial party. He hesitated in calling a leadership convention until October 1936. One week before the convention he presented his candidacy and on 28 October he was acclaimed party leader, promising a platform that would be “radical in the sense that the reform program of the Honourable R. B. Bennett was radical.” The Leader-Post (Regina) commented that he “thunders forth his convictions and ideas in resonant tones of purposeful youth.” For 18 months Diefenbaker ran the party from his law office while Cuelenaere carried the firm’s legal work. Diefenbaker appealed fruitlessly to the national party for financial aid and travelled the province seeking potential candidates. When a general election was called for June 1938 he was nominated in Arm River and took a personal loan to pay the nomination deposits for 21 other candidates. The party’s moderately progressive program called for refinancing the provincial debt, an adjustment of farm debts, a study of crop insurance or acreage payments, and a commitment in principle to public health insurance. The Conservatives were barely visible in a campaign dominated by the incumbent Liberals, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), and the Social Credit. The Liberal government was re-elected with 38 seats against 14 opponents, none of them Conservative. The Conservative Party’s vote fell to 12 per cent, but no one blamed the leader for the result. When the party met in convention four months later, Diefenbaker’s resignation was unanimously refused and he remained leader by default for two more years.

During the 1930s Diefenbaker served as defence counsel in four well-publicized murder trials. In The King v. Bajer his client, a destitute young woman with two children, was found not guilty of suffocating her newborn child. He was unsuccessful in The King v. Bohun, his client being found guilty of murdering a storekeeper. The jury’s recommendation for clemency was rejected and Steve Bohun was hanged in the Prince Albert jail in March 1934. After a raucous preliminary hearing in The King v. Fouquette, the crown stayed charges through lack of evidence and the murder remained unsolved. In The King v. Harms Diefenbaker called for a verdict of manslaughter in an unwitnessed alcoholic killing. John Harms was convicted of murder, but Diefenbaker successfully appealed on the ground of an improper charge to the jury. At the second trial he presented meticulous evidence of Harms’s intoxication and won conviction on the reduced charge. Harms was sentenced to a prison term of 15 years.

Diefenbaker’s political ambitions remained focused on national rather than provincial politics. By the spring of 1939 he was making tentative plans for a nomination in Lake Centre, the federal counterpart of his provincial constituency. On 15 June he was acclaimed the Conservative candidate and began intensive preparations for an election the following year. When Germany invaded Poland in September, the Conservative Party declared its solidarity with the King government’s declaration of war. Arrangements for the election campaign were suspended, and commenced again only when the house was dissolved in January 1940. King campaigned confidently as a wartime incumbent, while the Conservatives under Robert James Manion* were divided and disorganized. In Lake Centre, Diefenbaker called for a statutory floor price for wheat, asserted his own loyal service in World War I, and attacked the King government for its “marked tendency towards dictatorship.” The Liberal Party won an overwhelming majority on 26 March. Manion was defeated, but Diefenbaker gained a narrow victory as one of two successful Conservatives from Saskatchewan. After five successive electoral defeats, he would never suffer another.

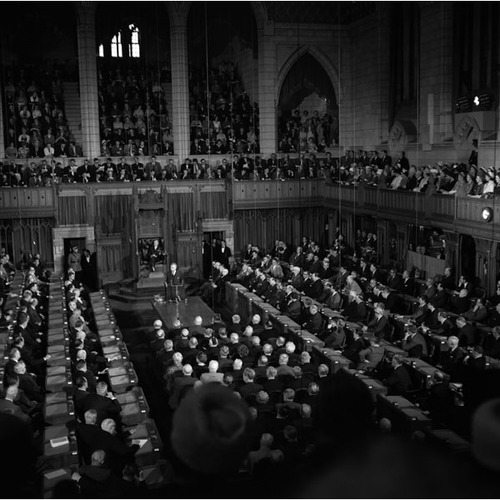

As one of 40 Conservatives in the new house, Diefenbaker was appointed to the house committee on the defence of Canada regulations, reviewing wartime emergency measures. He made his maiden speech on this subject with a strong declaration of patriotism, supporting wartime restriction of liberty and calling for national registration of adult males. Under the War Measures Act, the cabinet governed for the next five years by decree, while the role of the house was reduced to approval of the annual budget and spending estimates and modest questioning of the war effort within the self-imposed limits of general loyalty. Diefenbaker quickly established himself as one of the opposition’s most effective critics, emphasizing the need for conscription for overseas military service and criticizing the cabinet’s contempt for the role of parliament.

In the autumn of 1941 a meeting of the national party association chose the former leader, Senator Arthur Meighen, as Conservative chief. Meighen declared that he would pursue a program of coalition and resigned his senatorship to run in York South. The Liberal Party did not contest the by-election, but covertly aided the CCF candidate, who emerged victorious. This defeat – and the Liberal government’s political shrewdness – left the Conservatives in confusion. While Meighen pondered a leadership convention, a group of party activists met in Port Hope, Ont., in September 1942 to draft a progressive and internationalist program that might counter the growing challenge of the CCF. The conference reaffirmed the party’s belief in private enterprise and individual initiative, but also called for a wide range of social benefits and limited state intervention. When the leadership convention was scheduled for December, the chief organizers of the Port Hope conference were given prominent roles. Meanwhile, Meighen set out to arrange the draft of the Liberal-Progressive premier of Manitoba, John Bracken*, as party leader. When the convention opened in Winnipeg, four western candidates, including Diefenbaker, had declared themselves. Bracken joined the race at the last possible moment and won easily on the second ballot. Diefenbaker ran a respectable third. His nomination speech had incorporated the progressive vision of the Port Hope resolutions, together with a plea for the “preservation of Canada within the British Empire” and “the security of the common man.” He came out of the meeting with his reputation and friendships enhanced. The party had adopted a socially progressive platform satisfying to him and, at Bracken’s insistence, it would henceforth be known as the Progressive Conservative Party.

Since Bracken decided not to enter the commons, the Conservative caucus met to elect a new parliamentary leader when the house reconvened. Diefenbaker remained in the contest against Ontario mp Gordon Graydon through several ballots; but on the final one Diefenbaker announced that he would support Graydon, who won by a single vote.

The King government began its preparations for the post-war period when it declared in January 1944 that it was committed to a national program aimed at full employment, price stability, and a range of welfare measures. The first of these, a family allowance plan, was introduced in legislation that summer. Diefenbaker took the lead in persuading a reluctant Conservative caucus to support the proposal and led the party in debate on the bill, which was adopted unanimously in July. In the autumn the Liberal government confronted a crisis over the reinforcement of Canadian troops in Europe, reversing its policy and committing 16,000 home service conscripts for duty overseas. Diefenbaker and the Conservatives risked the loss of votes in Quebec by arguing unsuccessfully for full overseas conscription.

While King fought the general election of June 1945 on a forward-looking platform of welfare, national unity, and international cooperation, the Conservative Party under Bracken looked backwards in criticism of the Liberal war effort. As in 1940, Diefenbaker campaigned in Lake Centre on a personal platform. King lost seats to the Conservatives in Ontario and to the CCF in the west, returning to power with a bare majority of 125 seats. In Saskatchewan the only survivors of the CCF sweep were Gardiner for the Liberals, one independent Liberal, and Diefenbaker for the Tories.

Bracken led the party listlessly for three more years. Meanwhile, Diefenbaker solidified his reputation as an mp, supporting progressive causes and criticizing the government for maintaining wartime regulations in peacetime and ignoring the rights of individuals. In 1946 he proposed a bill of rights “under which freedom of religion, of speech, of association . . . freedom from capricious arrest and freedom under the rule of law” would be guaranteed. He told the house that his goal was to see “an unhyphenated nation” in which citizens of many origins and religions would be regarded and treated equally. The call for a Canadian bill of rights became his leitmotif.

Despite (and partly because of) his growing public reputation, Diefenbaker remained an outsider in the Conservative caucus, regarded by other members as aloof, temperamental, and too much the showman. In Ontario, party barons viewed him as erratic and unreliable. When he contested the leadership for the second time at the convention in the autumn of 1948, it was no surprise that he lost on the first ballot to the premier of Ontario, George Alexander Drew. On 27 June 1949 the Liberal government went to the polls under its new prime minister, Louis-Stephen St-Laurent, who campaigned on a bland program of prosperity and growth. The government’s majority increased and Conservative seats fell from 67 to 41, but in Saskatchewan Diefenbaker added almost 2,000 votes to his majority and remained the sole Conservative member.

During 1945-46 Edna Diefenbaker had suffered several months of illness, identified as severe depression, but she returned to good health in 1947. In the fall of 1950, however, she was diagnosed with acute leukaemia and she died in February 1951. In the House of Commons, three mps – Arthur Laing, Howard Charles Green*, and Gardiner – offered unprecedented eulogies to a colleague’s wife. For months Diefenbaker was overwhelmed by this loss. Two years later he married a childhood friend, the widowed Olive Freeman Palmer, a senior civil servant in Ontario’s Department of Education. For the rest of his political career, Olive gave John her loyal support, discreetly encouraging his ambitions and reinforcing his beliefs. Her regal presence on platforms at his side gave him strength and reassurance.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s Diefenbaker was uncertain about continuing his political career in the opposition. But his combative instincts were challenged by a brazenly partisan redistribution of parliamentary seats in 1952, which added potential Liberal and CCF voters to his Lake Centre constituency. With his private cooperation, an all-party committee arranged for his nomination in Prince Albert for the federal election of 10 Aug. 1953. In that campaign he made appearances for the Conservatives in four other provinces, but in Prince Albert he stood without party identification. He was returned again as the sole Conservative from Saskatchewan, while the party made slim inroads into what seemed to be a perpetual Liberal majority.

Public dissatisfaction over the long Liberal incumbency was gradually demonstrated over the next few years as Conservatives took power in New Brunswick under Hugh John Flemming* in 1952 and in Nova Scotia under Robert Lorne Stanfield* in 1956. In the summer of 1955 the St-Laurent government had stumbled and retreated in face of a Conservative filibuster over its attempted extension of emergency powers under the Defence Production Act, and in 1956 it confronted combined Conservative-CCF opposition in five weeks of parliamentary tumult over public financial assistance for construction of a natural gas pipeline. Diefenbaker, who was doubtful about the tactics of the filibuster, played a curiously low-key role in this struggle. In September 1956 Drew was unexpectedly forced by illness to resign from the party leadership. A convention was called for early December 1956.

Diefenbaker’s candidacy was taken for granted. It was boosted by support from vigorous provincial parties in Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Manitoba. Despite brief efforts to create a “Stop Diefenbaker” campaign in Ontario, he was the instant favourite over his opponents, Donald Methuen Fleming* and Edmund Davie Fulton*. In his nomination speech Diefenbaker called on the party to banish a sense of defeatism. According to his Quebec supporter Pierre Sévigny*, “As he proceeded, the magnetism of the man, the hypnotic qualities which were to entrance a whole nation came to the fore. He spoke with an obvious sincerity and an inspired fervour.” Diefenbaker won a decisive victory on the first ballot.

The Liberal government remained complacent as it prepared for an early summer election in 1957. By contrast, Diefenbaker, despite his 61 years, injected energy and ideas into his reviving party with the assistance of his policy adviser, Merril Warren Menzies. Inspired by Menzies, and in his own visionary language, Diefenbaker put forward a program of national economic development aimed primarily at growth in the Atlantic provinces, the north, and the west. For three months he led a feverish national campaign with the assistance of campaign manager Allister Grosart, advertising director Dalton Kingsley Camp*, and the efficient organization of Leslie Miscampbell Frost’s Ontario Conservative Party. In Quebec the party received discreet assistance from the Union Nationale machine of Premier Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*. With freshly enhanced funding the party was able to contribute generously to local campaigns in all provinces. Diefenbaker’s message to voters was positive, even utopian, recalling the party’s role in the country’s foundation under Sir John A. Macdonald*. “We intend to launch a National Policy of development in the Northern areas which may be called the New Frontier Policy,” he promised. “Macdonald was concerned with the opening of the West. We are concerned with developments in the Provinces . . . and in our Northern Frontier in particular. . . . The North, with all its vast resources and hidden wealth – the wonder and the challenge of the North must become our national consciousness.” The party campaigned on a personalized slogan, “It’s time for a Diefenbaker government,” and the country awoke on 10 June to a surprise Conservative victory of 112 seats to the Liberals’ 105; the CCF (with 25 seats) and Social Credit (with 19) held the balance of power. Diefenbaker took office on 17 June 1957 as leader of a minority government.

With over 60 new members in his caucus, Diefenbaker chose his cabinet entirely from sitting mps. These included D. M. Fleming in Finance, Fulton in Justice, Gordon Minto Churchill* in Trade and Commerce, Howard Green in Public Works, Douglas Scott Harkness* in Northern Affairs and National Resources, George Harris Hees* in Transport, George Randolph Pearkes* in National Defence, George Clyde Nowlan in National Revenue, Michael Starr in Labour, Léon Balcer as solicitor general, and Ellen Louks Fairclough, née Cook*, as secretary of state (the first woman to become a federal minister in Canada). In August Francis Alvin George Hamilton assumed the Northern Affairs portfolio and Harkness moved to Agriculture. The following month Diefenbaker drew his first minister from outside the house when Sidney Earle Smith*, then president of the University of Toronto, became minister of external affairs. Drew became the Canadian high commissioner in London. The cabinet seemed competent and workmanlike, but it noticeably lacked French-speaking ministers in major portfolios. This failing Diefenbaker never corrected.

In his administration’s early days Diefenbaker made a public commitment to divert 15 per cent of Canada’s foreign trade from the United States to the United Kingdom. The promise would remain unfulfilled despite his government’s continuing efforts to lessen dependence on the American market and to promote trade with the British Commonwealth. Beyond this initial misstep, the new government proceeded boldly with an ambitious legislative program of farm price supports, housing loans, aid for development projects across the country, tax reductions, and increases in old-age pensions and civil service salaries. Public opinion polls showed strong support for the new government. When the Liberal leader, Lester Bowles Pearson, moved a motion of no-confidence proposing that the Conservatives hand power back to the Liberals, Diefenbaker seized the occasion to request a dissolution of parliament for an election in March 1958.

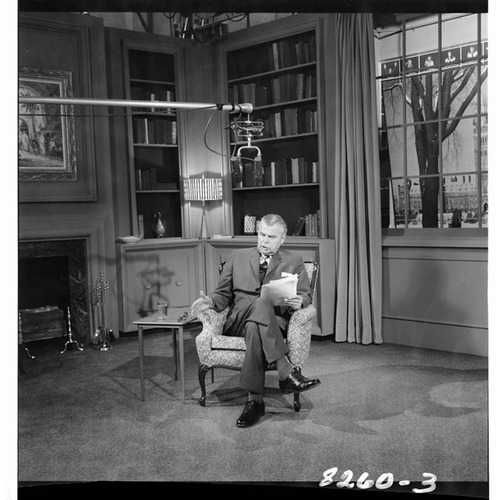

Diefenbaker’s 1958 platform was a simplified and more exuberant version of the party’s 1957 program, involving a new vision of the nation both economic and spiritual. He preached a populist, secular faith. “Everywhere I go,” he declared, “I see that uplift in people’s eyes that comes from raising their sights to see the Vision of Canada in days ahead.” Diefenbaker’s rhetoric caught the public mood. His campaign swept the country in a wave of euphoric enthusiasm. The posters called for voters to “Follow John” and the electorate responded by granting the Conservatives an astonishing 208 of 265 seats, including 50 in Quebec. In his victory speech Diefenbaker declared that “the Conservative Party has become a truly national party composed of all the people of Canada of all races united in the concept of one Canada.” His “Vision” had raised public expectations beyond the possibility of satisfaction. He would need rare skill and good fortune to avoid a crashing descent from those heights.

Diefenbaker was soon accused of running a one-man government. This charge was true in the sense that his election victories and the political system focused public attention on his leadership, but untrue as a description of the governing process. In opposition he had been a loner in the Conservative caucus and in power he took pride in his dominating presence. He tended to distrust close advisers and was not at ease with his intellectual superiors – although he relied heavily on his clerk of the Privy Council, Robert Broughton Bryce. His cabinets contained few ministers of brilliance and he had no inclination to bring along potential successors. Throughout his term of office he held endless cabinet meetings in search of consensus, delayed decisions out of uncertainty, and (in the absence of crisis) left his ministers to manage their own departments with unusual freedom of action. Diefenbaker was neither an imaginative policy maker nor a skilled compromiser, preferring the stimulation of the hustings and debate in the house to any long-term promotion and brokering of his ideas. As he came under increasing attack, his suspicions, his tenacious fighting instincts, and his talent for the dramatic overwhelmed his capacity for calm judgement and his ability to lead a united political team.

The prime minister’s initial decisions in foreign and defence policy, however, were taken confidently and decisively. They involved Canada’s defence relationship with the United States, and were made in an atmosphere of cordiality with the American administration of President Dwight David Eisenhower – whose view of the threat from the Soviet Union during the Cold War was fully shared by Diefenbaker. The decisions grew naturally out of cooperation between the previous Liberal government and the United States and intensified Canadian absorption into the American military system. In July 1957 Diefenbaker and defence minister Pearkes – acting without consultation in cabinet – committed Canada to participation in the integrated North American Air Defence Agreement, known as NORAD. In 1958 Diefenbaker agreed with the United States to locate two short-range Bomarc anti-aircraft missile bases in northern Ontario and Quebec and to arm the missiles, once installed, with nuclear warheads. This decision at first caused little controversy.

In February 1959 (after ambiguous warnings had been delivered to the manufacturers in previous months) Diefenbaker announced the immediate cancellation of development of the Avro Arrow (CF-105), a Canadian-designed, advanced interceptor aircraft being built in Toronto. The Arrow decision raised questions about the government’s style and judgement and eventually weakened Diefenbaker’s confidence in his own political intuitions. In subsequent years the Arrow would become a cult symbol of mistakenly abandoned Canadian industrial and military opportunities, although in the cooler light of financial and military prudence the decision could easily be justified.

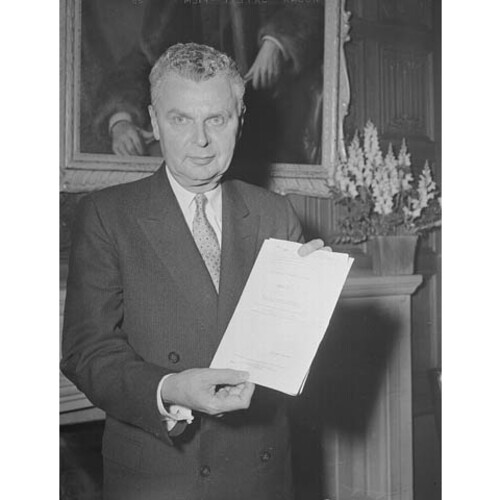

In opposition Diefenbaker had been a renowned champion of civil liberties. In 1958, as prime minister, he promised to protect rights “defined and guaranteed in precise and practical terms to all men by the law of the land.” After two years of intense discussion on the merits of a constitutional amendment binding on all levels of government versus the passage of declaratory federal legislation, he opted for an ordinary act of parliament which would not become lost in controversy over amending the constitution. The bill, he declared, would serve to educate citizens on their existing rights and would act as a restraint and a guide for federal lawmakers. Diefenbaker acknowledged – in the absence of a constitutional amendment – that his bill was only a first step for Canada, but it was nevertheless a pledge to all citizens that their rights would henceforth be respected. He told the house what this change would mean for him: “I know something of what it has meant in the past for some to regard those with names of other than British or French origin as not being that kind of Canadian that those of British or French origin could claim to be.” The bill was adopted unanimously in August 1960, and in retrospect Diefenbaker regarded it as his outstanding achievement. It contained two escape clauses, one permitting parliament to override the guarantees contained in the act, providing legislation specified that it had been adopted “notwithstanding the Canadian Bill of Rights,” and a second exemption for actions taken under the War Measures Act. The act was interpreted cautiously by the courts, but had an exemplary political importance. Under Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau*, it would be transmuted into the more comprehensive Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, containing the same exemptions. In 1960 as well, parliament extended the federal franchise to Canada’s aboriginal population.

The following year the Diefenbaker cabinet dealt with another issue of conscience long troubling to the prime minister. For three years after assuming power, cabinet had reviewed every criminal conviction involving the death penalty in time-consuming and anguishing detail, confirming some sentences and commuting others. Their task was eased after passage of justice minister Fulton’s amendments to the Criminal Code, which created two categories of murder and limited the death penalty to a narrow range of deliberate offences.

The Diefenbaker government’s first budget, in 1958, had held the line on further spending in the face of an economic slowdown, but the prime minister’s preference for aid to prairie farmers and an uncoordinated program of development projects in the Atlantic provinces and the west progressively undermined the highly conservative instincts of finance minister Fleming. Annual budgets fell into deficit. Beyond his conviction that fairness required a new concern for the poor, the unemployed, the ill, and the elderly, Diefenbaker lacked any coherent economic strategy. As unemployment continued to grow in 1959, 1960, and 1961 despite infusions of fresh public spending, he was troubled by Liberal claims that “Tory times are hard times” and haunted by memories of Bennett’s loss of power in 1935. Under relentless pressure from the cabinet for expansionary policies, Fleming came to share Diefenbaker’s belief that the restoration of prosperity was hindered by the Bank of Canada’s restrictive interest rate policy and the outspokenness of its governor, James Elliott Coyne*. For five months in 1961 Diefenbaker and Fleming engaged in an unseemly public battle with the governor, as they sought his resignation. Coyne’s refusal prompted the government to introduce legislation dismissing him, but that was frustrated by a Liberal majority in the Senate. On 14 July, once Coyne was allowed to make his case before a Senate committee, he offered the resignation he had previously refused. The conflict resulted in agreements between the bank and the government to avoid similar disputes in the future, but the immediate political effect was to undermine popular faith in the competence of the Diefenbaker regime.

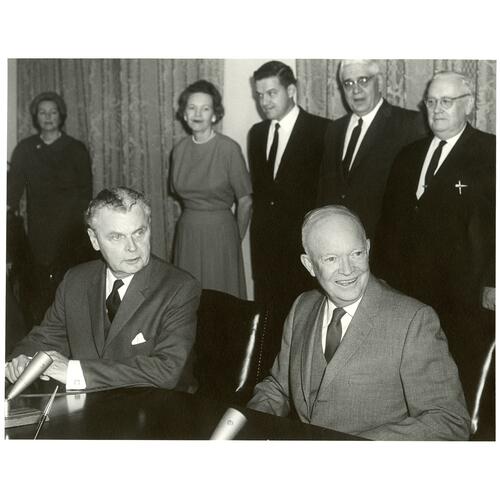

As prime minister, Diefenbaker was eager to make an impact on the international scene equalling that of his political rival Pearson. In the summer of 1958 he had welcomed both the British prime minister, Maurice Harold Macmillan, and the American president, Eisenhower, to Ottawa and in the autumn of that year he toured Europe and the Asian Commonwealth. In Europe he gained the respect of President Charles de Gaulle of France, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer of the German Federal Republic, and Prime Minister Amintore Fanfani of Italy. In Asia he admired the anti-communism of the new Pakistani dictator General Mohammad Ayub Khan and the political realism of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru of India, while warning against the neutralism of Prime Minister Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike of Ceylon (Sri Lanka). He made a major speech to the General Assembly of the United Nations on 26 Sept. 1960, denouncing the Soviet Union for its domestic tyranny, its crude colonialism in eastern and central Europe, and its threats to the western alliance. The speech evoked praise from other western leaders.

Despite his vehement rejection of the South African policy of apartheid, Diefenbaker was hesitant to consider exclusion of South Africa from membership in the British Commonwealth on the ground that the association should not interfere in the domestic affairs of its members. Political pressure for action intensified after disorders and a police massacre of peaceful demonstrators in Sharpeville in March 1960. At a meeting of Commonwealth prime ministers in May Diefenbaker worked with Prime Minister Macmillan to avoid a split among the leaders along racial lines. They found their escape in convenient delay. The conference offered South Africa time to revise its policies by agreeing that in the event it chose to become a republic, it would have to request consent from other Commonwealth members for readmission to the association. When South Africa’s whites voted that October in favour of a republic, Prime Minister Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd announced that he would seek continuing Commonwealth membership at the meeting in March 1961. Diefenbaker arrived at that meeting carrying divided counsels on South Africa, some calling for its exclusion, some for renewal of its membership coupled with a Commonwealth statement on racial equality, and others for further delay. As the conference opened he was undecided, but at the suggestion of Bryce he advocated a declaration of principles to be adopted before a decision on South Africa’s readmission. The effect would be to force a choice on South Africa rather than on the other members. When Verwoerd called for additional wording which would exclude his country’s practices from blame, Diefenbaker sided with the non-white leaders in rejecting the proposal. Verwoerd withdrew the South African application and left the meeting. Following South Africa’s departure, the conference dropped the effort to adopt a declaration of principles, but Diefenbaker told reporters that non-discrimination was an “unwritten principle” of the association and that it was “in keeping with the course of my life.” He accepted the outcome as the least divisive one possible and received wide praise at home and abroad for his defence of the principle of non-discrimination.

As president of the United States, Eisenhower had showed constant respect and consideration toward his northern colleague. Potential points of friction in joint defence policy and other matters were handled from Washington with amicable deference or delay. As his last official act before departing office, Eisenhower invited Diefenbaker to the White House for a ceremonial signing of the contentious Columbia River Treaty on 17 Jan. 1961. The easy political relationship died when John Fitzgerald Kennedy became president. Kennedy was young, brash, wealthy, and an eastern sophisticate whose manner grated on the prime minister. To Diefenbaker’s intense annoyance, Kennedy called him “Diefenbawker” when he first became president. Although their initial meeting in Washington on 20 February was superficially cordial, Kennedy told his brother Robert Francis that “I don’t want to see that boring son of a bitch again,” and the American administration began almost at once to show impatience over Canada’s hesitation to negotiate agreements on dual control of the nuclear warheads intended for Canadian Bomarc missiles. When Kennedy visited Ottawa in May 1961 tensions intensified. Diefenbaker explained his political difficulty in accepting possession of nuclear warheads in the face of growing anti-nuclear sentiment across the country; Kennedy responded that failure to arm the new weapons would turn Canada into a neutralist in the Cold War. When Diefenbaker accidentally discovered a confidential White House memorandum advising Kennedy “to push” Canada on a number of issues, the prime minister chose to ignore the advice of his staff to return it, instead filing it away for potential future use against the president. (It would be leaked during the 1963 election campaign.) Formal negotiations for an agreement on the warheads made no progress in this atmosphere of distrust – although at the time Kennedy made no public complaint over Canada’s hesitation.

Meanwhile, the Diefenbaker government’s good relations with the British government were fading. Macmillan’s initial respect cooled as Diefenbaker took an unexpectedly strong and decisive position on the subject of South African membership in the Commonwealth, and effectively disappeared when Canada criticized the British application for entry into the European Economic Community, or Common Market. Diefenbaker and his high commissioner, Drew, regarded the application as a betrayal of Canada’s sentiments and economic interests and acted to subvert its success in the absence of firm trading guarantees for Commonwealth members. Diefenbaker made frequent complaints about Britain’s lack of consultation with its Commonwealth partners on the subject and privately took satisfaction at hints of French intransigence. (The British application would be vetoed by President de Gaulle in January 1963.) Canadian opinion on the matter was divided, but the Canadian government’s reputation was undermined by comments in the press that it had been overbearing and obstructive in its reaction to British policy.

In Quebec the Quiet Revolution was transforming the province and elsewhere appeals were mounting for fairer treatment of the country’s French-speaking minority. Diefenbaker, who had neglected the French-speaking members of his own caucus, was indifferent to the signs of change. He refused to consider proposals for a royal commission on French-English relations. In Ottawa the formerly admiring press gallery had grown disillusioned and hostile as the government’s record revealed an ineptitude frequently traceable to the prime minister’s character. Diefenbaker’s disorganization and growing indecisiveness had discouraged and divided his cabinet. When the commons was dissolved for a general election to be held on 18 June 1962, reporter James Stewart of the Montreal Star described the entire parliamentary term as “sometimes aimless, often ill-tempered, and always potentially explosive.” As the election campaign began, the government faced a major monetary crisis. A lingering recession, a series of budget deficits, an unfavourable balance in the current trade account, and general uncertainty about government policy provoked a loss of confidence in the exchange market. For weeks the Bank of Canada sold foreign reserves to maintain the value of the floating Canadian dollar and in May the cabinet was forced to devalue and peg the dollar at 92.5 cents (U.S.) in order to prevent a cascading collapse of the currency. The devaluation was cruelly caricatured by the press and the opposition during the election campaign; phoney Diefendollars or Diefenbucks passed from hand to hand.

Diefenbaker campaigned defiantly in the face of vigorous opposition from the refreshed Liberal Party, from the newly formed New Democratic Party, and in rural Quebec from the Ralliement des Créditistes, which under its charismatic leader, Réal Caouette, had been allied with the Social Credit Party since 1961. The Conservative program offered no novelty. The Toronto Globe and Mail reported that “the Conservative campaign has been essentially a one-man show with Mr. Diefenbaker the man. If they fail to win, he must take the blame; if they do win he can claim the victory, no matter how many seats they lose, for his own.” For Diefenbaker, the election results were devastating. He kept his hold on the prairies, but in the Atlantic provinces, rural Quebec, urban Ontario, and British Columbia the Conservatives lost their dominance. Five ministers were defeated. Diefenbaker held 116 seats against 100 Liberals, 30 Social Crediters/Créditistes, and 19 New Democrats. Following the campaign, a new run on the dollar required the imposition of tariff surcharges, reduced government spending, and emergency borrowing from the International Monetary Fund, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Diefenbaker retreated into weeks of seclusion before reconstructing his cabinet and reconvening parliament in the autumn.

The cabinet was directionless. Up to a third of Diefenbaker’s ministers speculated openly but indecisively on the prime minister’s removal. In October 1962 the Cuban missile crisis diverted everyone’s attention and Diefenbaker deepened his cabinet’s divisions by responding hesitantly to President Kennedy’s appeal for allied solidarity. In the aftermath, ministers insisted that negotiations with the United States on the acceptance of nuclear warheads should be reopened. The sudden impact of the international crisis and the prime minister’s demonstrated inability to make decisions under pressure suggested that an agreement with the United States to supply the warheads had become a matter of urgency. Negotiations quickly foundered and Washington raised the stakes by accusing the Diefenbaker government of lying and neglecting its military obligations. Diefenbaker’s minister of defence, Douglas Harkness, resigned. The opposition united to condemn Diefenbaker’s indecision and on 5 Feb. 1963 his government was defeated in the house.

Diefenbaker entered the 1963 election campaign with a disintegrating cabinet. Harkness, Hees, Sévigny, Fleming, Fulton, and others had resigned or retired. His supporting newspapers, the Toronto Telegram, the Globe and Mail, and all but four other papers across the country, had abandoned him. The party organization had collapsed – although his chief campaigners, Grosart and Camp, maintained their loyalty. Diefenbaker set out on the campaign trail fighting “the Bay Street and St. James Street Tories,” the American government, and his Liberal challengers. As he crossed the country in a whistle-stop campaign, greeting voters at little railway stations in the bitter cold, he was inspired by American president Harry S. Truman’s “Give ‘em hell!” election of 1948. His rural, prairie, and small town public responded enthusiastically as he derided the Liberal Party and the American Department of State. Throughout the campaign Conservative support held steady while that of the Liberals declined until, on 8 April, Diefenbaker left Pearson five seats short of a majority. Diefenbaker resigned office and Pearson took power on 22 April, once he had received an assurance of support from six Créditiste mps. In 1963 the journalist Peter Charles Newman published his vivid, best-selling account of Diefenbaker’s career, Renegade in power, the first of a new Canadian genre of popular contemporary history, which romanticized the prime minister’s dramatic rise and fall.

For three and a half years Diefenbaker carried on as leader of the opposition under siege from elements of his own party, but aggressive and menacing towards his Liberal opponents in the house. He ferreted out one embarrassing scandal after another – all of them involving Quebec ministers. The majority of his mps, dependent on him for their success in politics, remained faithful. For eight months in 1964 Diefenbaker and his loyalists delayed approval of a new Canadian maple leaf flag because they said it lacked any historic symbols. The resolution was eventually adopted in mid December after closure was used to cut off debate. Most of Diefenbaker’s Quebec mps voted with the government. Pearson, harassed and distracted by Diefenbaker’s relentless attacks in the house, called an election for 8 Nov. 1965, hoping to deliver a fatal blow to his nemesis. Old Conservative foes (including Hees and Fulton) returned to the fold in the hope of a political life after Diefenbaker, while the party leader himself dreamed of returning to power. At age 70 he conducted another vigorous national campaign. Pearson could find no clear theme beyond his call for a majority government and the final destruction of his foe, but he appeared to have little taste for the battle. Once more Diefenbaker’s Conservatives deprived the Liberal Party of its desired majority. The Conservatives, with 97 seats, held two more than previously, as did the Liberals with 131. The NDP, at 21 seats, gained four, while the Créditistes and Social Crediters (now separate) suffered losses.

By this time, the political conflict between Diefenbaker and Pearson had become malignant. The 1966 parliamentary year began with Diefenbaker’s renewed attacks on the government’s integrity, prompting countercharges against his own administration for having failed to act on a matter of security. A judicial inquiry under Mr Justice Wishart Flett Spence, appointed to examine what became known as the Munsinger affair, was in effect an ex post facto investigation of the political discretion exercised by the Diefenbaker government. Diefenbaker, Fulton, and their lawyers withdrew in protest from the inquiry midway through the hearings. The final report found no breach of security, but censured Diefenbaker for having failed to dismiss his associate minister of defence, Pierre Sévigny, six years earlier when he had learned of his extramarital liaison with Gerda Munsinger, who had apparently been a low-level Soviet agent. The Globe and Mail called the inquiry’s terms of reference “vague, vengeful, prosecutory . . . setting a precedent for endless witch-hunts as government succeeds government in Canada.”.

Diefenbaker’s second battle of the year was fought within his party, where he struggled to control the party office and the national association and to hold onto his own leadership. Eruptions of discontent multiplied, but in the absence of any formal system of leadership review he took for granted that his term was unlimited. Once convinced that the leader would not take voluntary retirement, the party president, Dalton Camp, proposed a reform in the party constitution to require an automatic vote on whether to hold a leadership convention subsequent to the loss of a general election. Diefenbaker met Camp’s challenge with charges of back stabbing, but failed to carry the annual meeting. It agreed on a leadership convention, to be held in 1967.

As planning for the convention proceeded, Diefenbaker refused to confirm his candidacy. Finally, he stood for re-election in opposition to a convention resolution emerging from the party’s policy conference at Montmorency falls, Que., that spoke of Canada’s “two founding peoples” or “deux nations.” (The draft resolution actually described a country “composed of the original inhabitants of this land and the two founding peoples [deux nations] with historic rights, who have been and continue to be joined by people from many lands.”) “That proposition,” he told reporters, “will place all Canadians who are of other racial origins than English and French in a secondary position. All through my life, one of the things I’ve tried to do is to bring about in this nation citizenship not dependent on race or colour, blood counts or origin.” Diefenbaker’s vision of “One Canada” meant equality for individuals and regions, but he could not accept the notion of “founding peoples” or “nations” which seemed to include some communities while excluding others. His familiar appeal to equality – always drawing on his personal experience – did not work in a period when the country had grown more complex. On the first ballot, he ran fifth behind Stanfield, Dufferin Roblin, Fulton, and Hees. He remained on the ballot through three votes. Stanfield was chosen leader on the fourth.

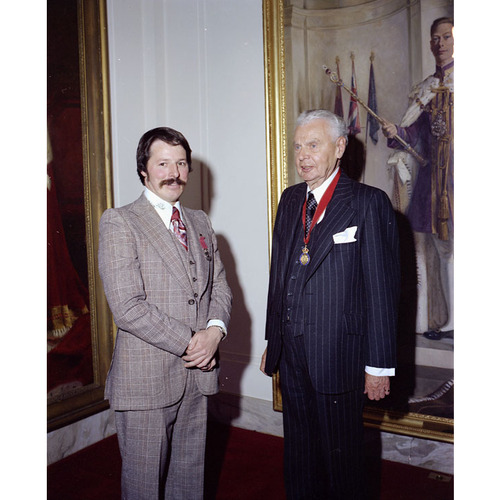

Through 12 more years and four more general elections, 1968, 1972, 1974, and 1979, Diefenbaker remained in the House of Commons. For a few years his prominent claque on the Conservative backbenches made life awkward for the new leader and for the rest of his life he could rivet the house’s attention and embarrass ministers with his pungent and sarcastic questions. On his 30th anniversary as an mp, in 1970, he joked that he would live as long as Moses. Six years later he was named a ch in the queen’s New Year’s honours list and he travelled proudly to England for the presentation ceremony at Windsor Castle. In the mid 1970s he published three volumes of ghost-written memoirs. He conducted his last election campaign in ill health during the spring of 1979, returned to Ottawa, and died at home on 16 August.

Diefenbaker’s state funeral was the most elaborate in Canadian history. He had planned it meticulously in consultation with the secretary of state’s department. For three days the open casket lay in the parliamentary hall of honour before it was moved in a ceremonial parade to Christ Church Cathedral for an interfaith service. From Ottawa, an eight-car funeral train carried the coffin and more than 100 passengers westwards to Prince Albert and Saskatoon, with stops both scheduled and unscheduled for crowds along the way. On the high bluffs of the South Saskatchewan River, the old chief was buried beside the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker Centre, which had been constructed on the grounds of the University of Saskatchewan to house his papers and relics. The new Conservative prime minister, Charles Joseph (Joe) Clark, delivered the graveside eulogy, describing Diefenbaker as “the great populist of Canadian politics . . . an indomitable man, born to a minority group, raised in a minority region, leader of a minority party, who went on to change the very nature of his country and to change it permanently.” The body of his late wife Olive was moved from Ottawa to lie beside him.

Commentators and historians have not been kind to Canada’s 13th prime minister. J. L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer wrote that Diefenbaker’s memoirs, “arguably the most mendacious ever written by a Canadian politician, burnished his own image and refought all the old battles with only one victor. . . . Yet the record remained, one of deliberate divisiveness, scandalmongering, and mistrust.” Historian Michael Bliss – perhaps slightly kinder – judged that “Diefenbaker’s role as a prairie populist who tried to revolutionize the Conservative Party begins to loom larger than his personal idiosyncrasies. The difficulties he faced in the form of significant historical dilemmas seem less easy to resolve than Liberals and hostile journalists opined at the time. . . . But his contemporaries were also right in seeing some kind of disorder near the centre of his personality and his prime-ministership. The problems of leadership, authority, power, ego, and a mad time in history overwhelmed the prairie politician with the odd name.” For writer George Bowering, Diefenbaker was the wittiest of all the country’s prime ministers, “and he was the most amazing campaigner anyone would ever see or hear.” But he got everyone – the Americans, the British, the Liberals, the economists, the Quebecers, and his own party establishment – mad at him.

Diefenbaker’s entire adult life was aimed at a political career. He was moved by ambition and a sense of injustice that was both personal and regional, a determination to succeed at the centre of Canadian politics in Ottawa and in doing so confirm the equal rights of those he believed had been excluded from power and influence in Canada. His attitudes were shaped in the 1920s and 1930s, when Canadian public life was dominated by a privileged circle of Ontario and Quebec politicians in the Liberal and Conservative parties. With his personal and western preoccupations, however, he failed to sense the potential grievances of the French-speaking Canadian minority, who felt similarly excluded from a full role in national life.

Possessed of a rare determination that was reinforced rather than dulled by early slights and defeats, Diefenbaker had nurtured a dramatic and corrosive talent as a criminal defence lawyer which served him well as a member of the opposition, though less well as a member of government. He was a British Canadian with a sentimental attachment to the imperial connection and to Canada’s parliamentary institutions. His convictions on welfare and employment policy were shaped in the 1940s by his experience of the great depression on the prairies and were broadly shared by colleagues in the Liberal and CCF parties. In his approach to fiscal and monetary policy, on the other hand, he remained an instinctive conservative, never fully absorbing the lessons of Keynesian economics.

By temperament Diefenbaker was never a team player. Once he was in office, it was quickly evident that he could not produce harmony in his cabinet, nor could he master the technical complexities of financial, defence, and foreign policies. He was overwhelmed by the problems of administration and was relieved by the prospect of escape into the House of Commons or onto the hustings, where his talents as a populist preacher could be exuberantly exercised. There, he was melodramatic and overbearing, appealingly comical, whimsical, and sarcastic. He put on a great show. He was one of the last pre-television democratic leaders, who sought direction and self-confidence by face-to-face and intuitive connection with his voters rather than by polls, focus groups, and opinion management. He nursed resentments and in his later adversity his sense of isolation gave rise to dark visions of persecution and conspiracy. In politics he had little more than two years of success in the midst of failure and frustration, but he retained a core of deeply committed loyalists to the end of his life and beyond. The federal Conservative Party that he had revived remained dominant in the prairie provinces for 25 years after he left the leadership.

The biography is based on the author’s Rogue Tory: the life and legend of John G. Diefenbaker (Toronto, 1995), which contains an exhaustive list of primary and secondary sources. The Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker Centre for the Study of Canada, Univ. of Saskatchewan (Saskatoon), holds the Diefenbaker papers along with some photographs, films, and other documents. A selection of the letters deposited at the Centre have been published: J. G. Diefenbaker et al., Personal letters of a public man: the family letters of John G. Diefenbaker, ed. Thad McIlroy (Toronto and New York, 1985). Diefenbaker’s memoirs are gathered under the general title One Canada: memoirs of the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker (3v., Toronto, 1975-77) and are divided into three periods: [1]: The crusading years, 1895-1956; [2]: The years of achievement, 1957-1962: [3]: The tumultuous years, 1962-1967. Library and Arch. Canada holds a microfilm copy of the Diefenbaker papers along with additional documentation, in particular files concerning the Diefenbaker government and various ministries. The following list mentions some of the most useful secondary sources.

Michael Bliss, Right honourable men: the descent of Canadian politics from Macdonald to Mulroney (Toronto, 1994). George Bowering, Egotists and autocrats: the prime ministers of Canada (Toronto, 1999). D. [K.] Camp, Gentlemen, players and politicians (Toronto and Montreal, 1970). John English, The life of Lester Pearson (2v., New York and Toronto, 1989-92), 2. D. M. Fleming, So very near: the political memoirs of the Honourable Donald M. Fleming (2v., Toronto, 1985), 2. Eddie Goodman, Life of the party: the memoirs of Eddie Goodman (Toronto, 1988). J. L. Granatstein, Canada, 1957-1967: the years of uncertainty and innovation (Toronto, 1986). J. L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer, Prime ministers: ranking Canada’s leaders (Toronto, 1999). Simma Holt, The other Mrs. Diefenbaker (Toronto and New York, 1982). Knowlton Nash, Kennedy and Diefenbaker: fear and loathing across the undefended border (Toronto, 1990). P. C. Newman, Renegade in power: the Diefenbaker years ([new ed.], Toronto, 1989). Patrick Nicholson, Vision and indecision (Don Mills, Ont., 1968). H. B. Robinson, Diefenbaker’s world: a populist in foreign affairs (Toronto, 1989). Pierre Sévigny, This game of politics (Toronto, 1965). Dick Spencer, Trumpets and drums: John Diefenbaker on the campaign trail (Vancouver and Toronto, 1994). Thomas Van Dusen, The chief (New York and Toronto, 1968). Garrett and Kevin Wilson, Diefenbaker for the defence (Toronto, 1988).

Cite This Article

Denis Smith, “DIEFENBAKER, JOHN GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 20, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/diefenbaker_john_george_20E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/diefenbaker_john_george_20E.html |

| Author of Article: | Denis Smith |

| Title of Article: | DIEFENBAKER, JOHN GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 20 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |