Source: Link

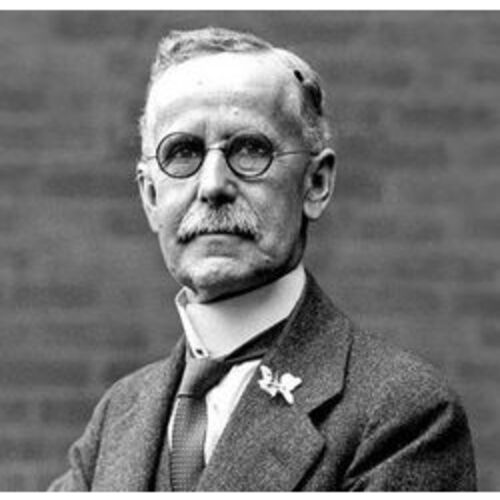

DOOLITTLE, PERRY ERNEST, cyclist, physician, surgeon, inventor, and automobilist; b. 22 March 1861 in Luton, Upper Canada, son of Ira Scott Doolittle and Sarah Jane Westover; m. 6 Oct. 1886 Emily Esther Pearson (1861–1956) in Toronto, and they had a son and a daughter; d. there 31 Dec. 1933 and was buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

Perry Doolittle was an enthusiast for bicycles and automobiles and an exemplar of the Canadians of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who embraced these new means of transportation. He was born into a Methodist family near Aylmer in southwestern Upper Canada; his father and mother were of English and German ancestry respectively. Perry attended Trinity Medical School in Toronto, graduating in 1885 with an md and cm (master of surgery). He then settled in the city and established a practice that he would maintain for the rest of his life, later specializing in electrotherapeutics (used to treat arthritis) and surgery.

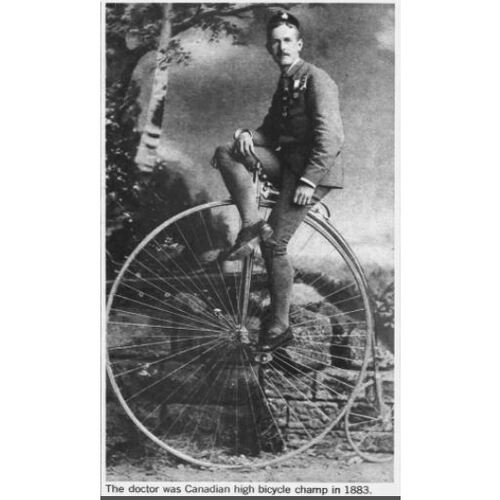

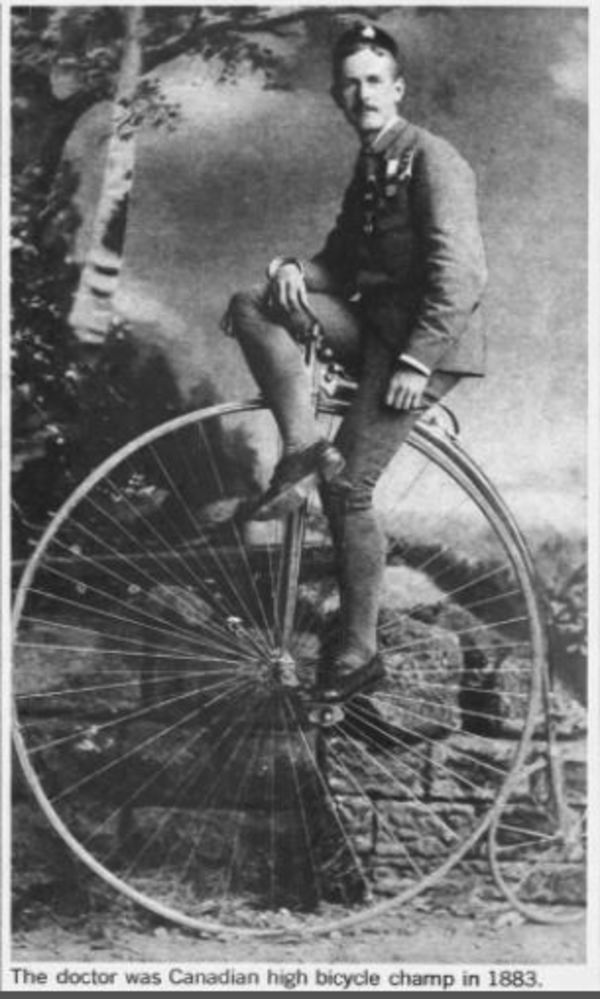

Doolittle’s first love was not medicine, but bicycles. He was given a bike at the age of seven, and as a teenager, after seeing illustrations in Scientific American (New York) of high-wheelers at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition, he constructed his own model, with a wooden frame and steel tires. His next bicycle, made of iron, had as a backbone the barrel of an old gun. Soon, he was racing. At the 1883 Canadian championships organized by the Canadian Wheelmen’s Association and held in London, Doolittle finished second in the five-mile race, which was officiated by sports journalist Philip Dansken Ross*. At the next year’s meet Doolittle triumphed in the half-mile no-hands race and the obstacle-course event. In all, he would win more than 50 competitions during his career.

Doolittle was an enthusiastic association builder. Hours after the 1883 race, he was elected vice-president of the Ontario-based CWA, which encouraged the building and maintenance of good roads across the country and briefly published a monthly journal, Bicycle (Hamilton), edited by journalist Walter Cameron Nichol*. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s Doolittle promoted the CWA, most notably by editing its 1895 travelogue, Wheel outings in Canada …, which he dedicated to Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon] and Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks]. Hoping to attract American tourists, Doolittle wrote, “If we can convince you that after all we are not a land of perpetual ice and snow, but that summer outings can nowhere else be found so enjoyable, we will have accomplished the task we have set ourselves.” He had stopped racing by 1890, but continued to ride recreationally and acted as surgeon to members of the Toronto Bicycle Club (Edmond Baird Ryckman, a future federal cabinet minister, was the secretary). An avid tinkerer on bikes, Doolittle was also an inventor: in 1896 and 1898 he patented hub brakes that were, for a time, commercially produced and widely used in Canada.

While on a trip to England in 1896 to obtain a British patent for his invention, Doolittle fell in love with the automobile. He soon became one of Canada’s most recognized car enthusiasts. “He drove for the sheer joy of it,” writers Hugh Durnford and Glenn Harry Baechler observe, “and wanted others to do the same.” In 1899 he made possibly the first used-car purchase in the country, buying a Winton from his friend James Robert Moodie, a Hamilton businessman. Doolittle was one of the first doctors in Toronto to use a car to make his rounds, and he organized early motorcades in the city, in which Moodie and merchant John Craig Eaton* were participants. Doolittle also invented the Doolittle Demountable Rim and other car parts. Not all of his ideas were successes, however: once, when he tried to seal two leaking tires on the Winton by filling them with molasses and milk instead of air, an odour that he called “indescribable” was released when one of them burst. In 1903 Doolittle was elected founding president of the Toronto Automobile Club, which became a part of the Ontario Motor League four years later. The league, in turn, was integral to the creation of the Canadian Automobile Federation in 1913. Doolittle chaired the inaugural meeting of the latter body, which renamed itself the Canadian Automobile Association in 1916. He would serve as its president from 1920 until his death.

A nationally recognized figure and a tireless advocate for more and better roads, Doolittle may deserve some credit for the Canada Highways Act [see Archibald William Campbell*], passed in 1919 by the Union government of Sir Robert Laird Borden. Two of Doolittle’s acquaintances, Ontario premier George Howard Ferguson* and New Brunswick premier Pierre-Jean Veniot, built roads that improved transportation in their provinces. Doolittle hoped to establish uniform traffic rules across the sprawling dominion, but this was hard to achieve: regulations were set locally and some provinces restricted the use of cars even after they appeared in numbers. (It was 1917, for example, before Prince Edward Island permitted their unlimited use, having first banned them and then allowing them to be driven only on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays.) Doolittle’s persistent lobbying nevertheless helped spark changes: in the early 1920s, after heated debates, the Maritime provinces and British Columbia switched from driving on the left side of the road to driving on the right, adopting the same practice as the rest of the country.

Doolittle completed several cross-country automobile trips, the most famous of which was made in 1925, when he drove from Halifax to Vancouver in a Model T produced by Gordon Morton McGregor*’s Ford Motor Company of Canada, which sponsored the journey. He hoped to claim the gold medal offered by Albert Edward Todd*, a founder of the Canadian Highway Association, for the first person to drive across Canada. During the 40-day trip, Doolittle spoke often to crowds who came out to see him, drawing attention to the problems faced by motorists and stressing the need to complete a highway across Canada. Once it was finished, he predicted, “We will be more than ever united by bonds of friendship and acquaintance from coast to coast.” Owing to a lack of suitable roads, however, he had to drive with flanged railroad wheels on tracks for more than 800 miles of the journey, thus breaking a rule that the vehicle must remain on the road at all times, which cost him the Todd Medal. (The feat of driving across the dominion solely by road would not be accomplished until 1946.) Later, he received an award of a different kind: in August 1928, at a Toronto luncheon attended by such prominent figures as Premier Ferguson, Mayor Samuel McBride, and car makers Thomas Alexander Russell and Robert Samuel McLaughlin*, Doolittle was given a cheque for $5,000 from the country’s “automobile men” in recognition of his “years of work in promoting automotive and highway affairs.”

Perry Doolittle, who would later be hailed by the CAA as the “King of Canadian Roads,” died of pneumonia, after several years of battling prostate cancer, on New Year’s Eve in 1933. He was 72 years of age. Russell and Premier George Stewart Henry* were honorary pall-bearers at the funeral. At the CAA’s 1934 convention, delegates “stood with bowed heads in silent tribute to the memory of Dr. Doolittle … and in rededication of the association to the great objectives to which he had so unstintingly devoted his great energy and talents – the completion of the Trans-Canada Highway and the unification of traffic regulations throughout the Dominion.” Although he did not live to see the cross-country route finished – it would be officially opened by Prime Minister John George Diefenbaker* in 1962 – Perry Doolittle is regarded, in the words of the CAA, as the “spiritual father of the Trans-Canada Highway.”

Perry Ernest Doolittle is the editor of Wheel outings in Canada and C.W.A. hotel guide (Toronto, 1895). UTARMS holds a clippings file, A1973-0026/086(60), that contains newspaper accounts of some of his public speeches. Several of Doolittle’s patents are available on the Google patents website, including his “Brake mechanism for bicycles”: www.google.com/patents/US576560 (consulted 29 June 2017) and his “Detachable rim for pneumatic tires”: www.google.com/patents/US1018238 (consulted 29 June 2017).

Globe, 3 July 1883; 16 May 1925; 28 Aug. 1928; 1, 3 Jan., 28 Aug. 1934. I. J. Bates, “The great Canada bicycle tour – part I,” Outing and the Wheelman (Boston), 4 (April–September 1884): 97–106. “The C.W.A. meet,” Outing and the Wheelman, 4: 473–74. R. A. Collins, A great way to go: the automobile in Canada (Toronto, 1969). D. F. Davis, “Dependent motorization: Canada and the automobile to the 1930s,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 21 (1986–87), no.3: 106–32. F. A. de Luna, “Rules of the road: left, right or down the middle?,” Beaver (Winnipeg), 73 (1993), no.4: 17–21. Hugh Durnford and Glenn Baechler, Cars of Canada (Toronto, 1973). H. English, “The Toronto Bicycle Club,” Outing (New York and London), 16 (April–September 1890): 490–91. Daniel Francis, A road for Canada: the illustrated story of the Trans-Canada Highway (Vancouver, 2006). F. G. Lenz, “What Frank G. Lenz, ‘Outing’s’ correspondent, says of Toronto,” Cycling (Toronto), 2 (26 Nov. 1891–10 Nov. 1892): 405. Glen Norcliffe, The ride to modernity: the bicycle in Canada, 1869–1900 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 2001).

Cite This Article

Dimitry Anastakis and Christopher Pennington, “DOOLITTLE, PERRY ERNEST,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/doolittle_perry_ernest_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/doolittle_perry_ernest_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Dimitry Anastakis and Christopher Pennington |

| Title of Article: | DOOLITTLE, PERRY ERNEST |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |