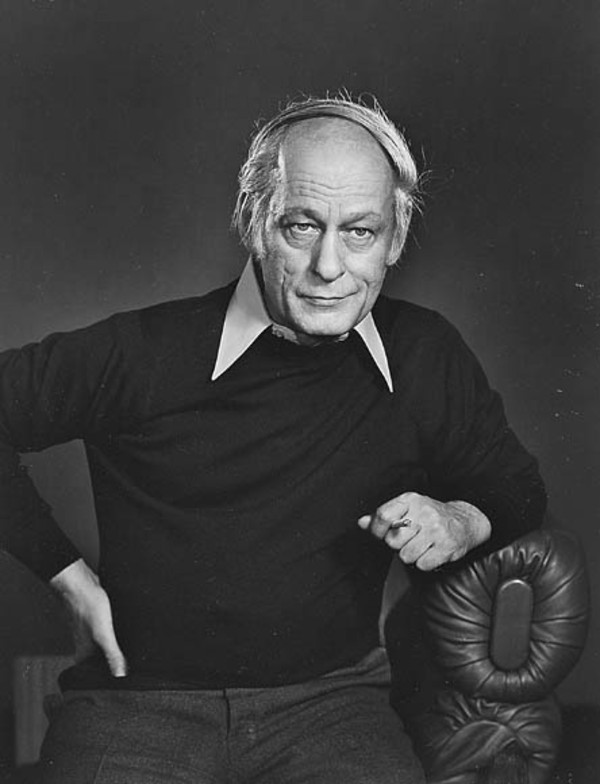

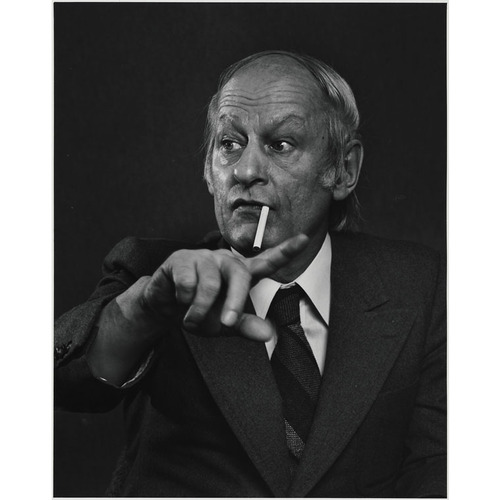

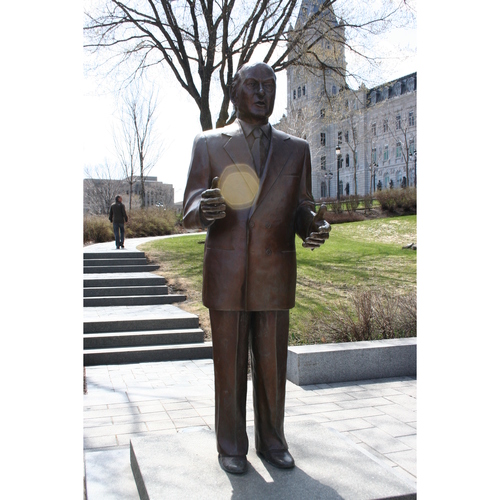

LÉVESQUE, RENÉ (baptized Charles-René), journalist, politician, and author; b. 24 Aug. 1922 in Campbellton, N.B., and baptized 10 September in New Carlisle, Que., the eldest son of Dominique Lévesque, a lawyer, and Diane Dionne; m. first 3 May 1947 Louise L’Heureux in Quebec City and they had two sons and a daughter; they divorced in 1978; m. secondly 12 April 1979 Corinne Côté (d. 2005) in Montreal; d. there 1 Nov. 1987 and was buried 5 November in the cemetery of Saint-Michel parish in Sillery (Quebec City).

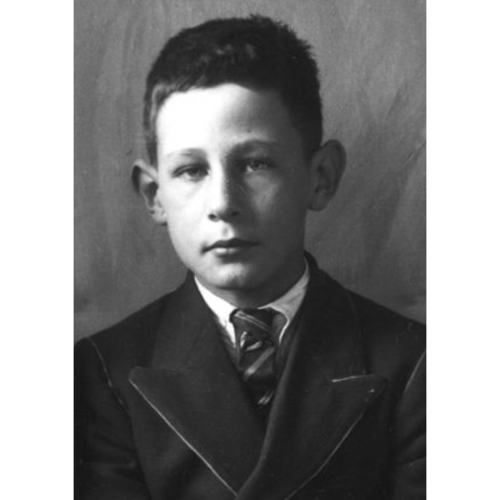

In the 1920s the south shore of the Gaspé, in the province of Quebec, had no hospital worthy of the name. Thus the quintessential Quebecer among the province’s premiers uttered his first cries in a hospital in New Brunswick, on the other side of Baie des Chaleurs. By his own account, René Lévesque enjoyed a happy childhood in New Carlisle by the sea, with a father he idolized, for whom the word “culture” had meaning, and a mother with a mercurial disposition like his own, which led to a relationship that was difficult, yet full of affection never put into words. He grew up in the unforgettable, remote Gaspé, with its cod fishers and its villages that ran down to the sea. According to his relatives and close friends, his lifelong marked compassion for the destitute and the common people stemmed from his roots in the Gaspé and his early contact with poverty and underdevelopment, even though he himself came from a well-to-do family. This attitude was probably also explained by the example set by the father he admired, of whom he would say that, lawyer though he was, he showed unconditional respect for others.

New Carlisle at that time had a population of not quite 1,300, of whom a third were French-speaking and subject to the dictates of the great loyalist families who had fled the American revolution and settled there in the 18th century. Two distinct societies, living side by side, they were a perfect symbol of Canada’s “two solitudes.” In this world, where English was required for making oneself understood, young René lost no time in becoming bilingual. He also discovered that the rich spoke English, lived in homes that looked like castles beside the modest houses of the francophones, and enjoyed a network of modern schools that showed his local one up for what it was: a “miserable shack more than a kilometre away from home,” as he put it in Attendez que je me rappelle …, the memoirs he was to publish in Montreal in 1986 (translated under the title Memoirs by Philip Stratford and published in Toronto in 1986).

Throughout his life Lévesque would present himself as a man of the people who would break away from his middle-class origins. His mother, Diane Dionne, was a doctor’s daughter and traced her lineage back to the seigneurs of Tilly, near Quebec City. His father, who came from Saint-Pacôme, in the Kamouraska region, was a prominent lawyer of the Quebec bar in the Gaspé. Before settling in New Carlisle and fitting himself into the French Canadian elite, allied to the loyalist “family compact” that ruled over the town, Dominique Lévesque had been a partner of Ernest Lapointe*, whose law office was in Rivière-du-Loup and who would become the Quebec lieutenant of Canadian prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King*. Young René’s rebellious streak ran in the family. One of his maternal ancestors, Germain Dionne, a rich farmer and bailiff of the seigneury of La Pocatière nostalgic for the French régime, had fought the British army alongside American insurgents during the rebellion in the colonies. On his father’s side, his ancestor Charles Pearson had mutinied when in the Royal Navy; after deserting his ship in the harbour at the mouth of the Rivière Ouelle, he had put down roots in the area and become the first miller of the seigneurial mill. In 1817 he married Marguerite Pastourel; their daughter Marcelline married Dominique Lévesque (René’s paternal great-grandfather), of the sixth generation of Lévesques originating in Normandy.

René Lévesque realized very early in life that he was born to be a leader. The eldest of four children, he made an impression on everyone, both at the local school in New Carlisle and at the Séminaire de Gaspé, where he began his classical studies in September 1933. When he arrived at the seminary, one of the first questions he asked its superior, Father Alphonse Hamel, was whether there was a library. He did not take well to discipline and had a calculating side to his personality, which was offset, however, by his obvious intellectual leadership. Having been introduced by his father to the great masters of French literature and to politics, he was brighter and more cultured than the average student. Conscious of his superiority, he did not make friends easily, preferring the company of such authors as Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas, Émile Zola, and Victor Hugo, whom he discovered in his father’s well-stocked library. Secretive by nature, he put up a wall against anyone who wanted to lead him into the realm of emotions and sentiments, and secretive he would remain throughout his life. But since he was a gifted student and took all the prizes, he was forgiven everything.

René’s Jesuit teachers, including Charles Dubé, a cousin of the famous François Hertel [Rodolphe Dubé], pampered him, while at the same time making him aware of the nationalist ferment and its causes, the economic and social inferiority of French Canadians that was intensified by the grinding poverty of the 1930s. In his memoirs, Lévesque would acknowledge that he had liked Hertel’s iconoclastic book, Leur inquiétude (Montreal, 1936), whose clear conclusion predicted that Quebec would separate from Canada some day. At a public meeting held in the seminary courtyard during the 1935 election campaign, he heard the nationalistic diatribe of Philippe Hamel*, a dentist and popular speaker for the Action Libérale Nationale, against the grip of “foreign trusts” on the lives of French Canadians. At the age of 13, he asked the existential question in the seminary’s newspaper “L’Envol”: Why remain French? His conclusion showed how precise his political thinking had already become and foreshadowed the realistic nationalist politician he would be, while also revealing a vaguely vengeful sentiment: “Let’s demand from the Jews and the Americans, not the insignificant positions that we now hold, but the high positions to which we are entitled. From the day when that is accomplished, we will be able to call ourselves masters in our own house.”

In June 1937, when René was 14 years old, tragedy struck him. His father, whom he would describe in his memoirs as the most important man in his life, died at the age of 48 in a hospital in Quebec City. As the summer of 1938 came to an end, René was transplanted from his native Baie des Chaleurs region to that city. He saw his mother’s swift remarriage in January 1939 as a betrayal. Diane Dionne wed Albert Pelletier, a lawyer with connections to the separatist Quebec City weekly La Nation, whose influence on René would be significant, despite their troubled relationship. Lacking the strictness of the father he had idolized, and at odds with his mother, he gradually lost interest in his studies. He had shone in the sixth year (Rhetoric) just as he had in the Gaspé, but at the beginning of 1940, while he was in the first year of the Philosophy program, the authorities of the Collège des Jésuites Saint Charles Garnier expelled him because he had slipped to wretchedly low marks. He was accepted at the Séminaire de Québec, where he concluded his classical studies with difficulty in 1941. He then enrolled at the law faculty of the Université Laval, but abandoned his studies in 1943, to the great despair of his mother.

Lévesque chose a Bohemian lifestyle, chasing girls and playing poker with Jean Marchand and Robert Cliche*, two Université Laval students destined, as he was, to become famous, and he dreamed of becoming a writer. A budding playwright, he co-authored with Lucien Côté “Princesse à marier,” a “light-hearted and highly imaginative little piece,” which he had staged at the Palais Montcalm in Quebec City. The play was a monumental flop. This failure did not keep him from making a second and last foray into the world of drama. Probably in 1943 he wrote a piece for radio entitled “Aux quatre vents.” The play would not be produced until it was rediscovered half a century later; it would be published in Montreal in 1999. In this work the 20-year-old Lévesque seems pessimistic about the future of the French Canadians of his time, whom he portrayed as reduced to a people made invisible by history. “Aux quatre vents” also foreshadowed the René Lévesque of the years to come. Indeed, what would he do with his life if not spend it all trying to liberate those French Canadians – who came to regard themselves as Quebecers – from their invisibility?

In fact, Lévesque’s true passion was radio journalism, which he had discovered earlier at CHNC, in New Carlisle, during the summer of 1938, his last in the Gaspé. While he was gaining experience in Quebec City at the private radio station CKCV on Carré D’Youville, and then at CBV, a regional station of Radio-Canada, the French-language network of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, in the Château Frontenac, World War II broke out. Like the many Quebecers of his generation who were loath to shed their blood for the commonwealth, Lévesque was opposed to conscription, an issue that was tearing Canada apart. But General Charles de Gaulle’s appeal to occupied France in June 1940 shook his convictions. The Nazis were threatening freedom and democracy. This was the challenge of his generation; he could not wash his hands of it.

In the fall of 1943 Lévesque was 21 years old. He was called up. He was quite willing to go and see the war that he was describing to his listeners on CBV, but with a microphone, not a gun. He pleaded first with his immediate superiors at Radio-Canada, who managed to have his military training postponed until sometime in January 1944. Shortly before that fateful date, he made a vain attempt to persuade the director general of Radio-Canada to find him a job as a war correspondent in one of its overseas teams. It was Uncle Sam who saved him from military service. As it happened, the American Office of War Information was recruiting bilingual information agents like him. And so, in May 1944 he was in London, attached to the French section of Voice of America / La Voix de l’Amérique, a program of the American Broadcasting Station in Europe that had been set up by the Americans and was flooding the occupied countries, particularly France, with propaganda. In June, when the Allies landed on French soil, Lévesque was eager to get to the line of fire, but his wartime odyssey did not really begin until February 1945. Holding the rank of junior lieutenant, he joined General Omar Nelson Bradley’s army, which had liberated part of France and then stopped in Paris. Next came the march to the German border with General George Smith Patton and General Alexander McCarrell Patch, the crossing of the Rhine, and the discovery of a shattered Germany with its great cities, such as Nuremberg, Stuttgart, and Munich, devastated. Finally, there was the horror of the Holocaust, which turned his stomach when he entered the concentration camp at Dachau with the first group of American journalists.

When Lévesque went back home in the fall of 1945, a gulf separated him from the apprentice journalist of pre-war years. All his life he would repeatedly utter warnings, insisting that every society has the potential for returning to the jungle and barbarism. He would always be suspicious of the possible blunders of the Quebec nationalism that he himself would nonetheless strongly and rationally personify.

Radio-Canada came to Lévesque’s rescue by opening its doors to him in late October 1945. Despite the feeble voice he had brought back from the war, he became an announcer on La Voix du Canada, a daily news program produced by the international service of Radio-Canada and broadcast from Montreal to France and other French-speaking countries and territories. Lévesque presented Canadian current affairs in four parts: news, documentaries, news reports, and cultural events. He would stay at this job for nearly eight years. He also found refuge in marriage, children, and family life. On 3 May 1947 he pledged his loyalty to Louise L’Heureux, his fiancée since before the war.

At Radio-Canada, Lévesque was not restricted to his work with La Voix du Canada (which was sometimes broadcast in Canada). He could also be heard nationally. After hosting Journalistes au micro (1949–50), he would work simultaneously on La Revue de l’actualité (1951–54) and La Revue des arts et lettres (1952–54), where he gave highly critical film reviews. Within a few years he established himself as one of Radio-Canada’s leading lights. Imaginative but unmethodical, he loved doing on-the-spot reports. Those he wrote from Korea, where he was a war correspondent from July to September 1951, made his reputation as a great international reporter. During these years he worked closely with Judith Jasmin*, with whom he carried on a love affair. Though he did not look the part, he was considered at the time the Don Juan of Radio-Canada. There was something appealing about him. He loved women and they responded to him in kind. In October 1951 he and Jasmin were assigned to cover the visit of Princess Elizabeth and her husband, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, to Canada. From January 1954 they were co-hosts of Carrefour, a new radio program devoted to news reports. But soon the rising medium of television shunned him. Lévesque was no Adonis. Short and balding, he had tics and smoked like a chimney. Yet his lively interview with some Russian schoolgirls on Red Square in the fall of 1955 was a sensation on the television news. Radio-Canada had assigned him for radio but also for television – just this once would not hurt – to cover the visit of Lester Bowles Pearson*, Canada’s minister of external affairs and future prime minister, to the Soviet Union. When the intransigent Nikita Khrushchev mistreated Pearson in Lévesque’s presence, the special correspondent for Radio-Canada got his first international scoop. In 1956, though his bosses at Radio-Canada doubted he had the looks for the job, Lévesque finally made the leap to television and quickly rose to the rank of “god of the TV screen,” to quote Georges-Émile Lapalme, leader of the provincial Liberal Party. On Point de mire, a cult program of the late 1950s, he used his passion for teaching and communicating to explain the world’s great dramatic events, such as the Suez crisis and the war in Algeria. It was at this time that the born seducer began a secret love affair with a young actress who, in 1958, bore him a daughter he would never acknowledge. This extramarital paternity prompted Louise L’Heureux to begin divorce proceedings, but she subsequently dropped them.

In December 1958 the producers at Radio-Canada went on strike for the right to form a union. The strike soon became politicized and foreshadowed the turmoil of the 1960s. This event, in which Lévesque was deeply involved, marked a turning point in his career. He went into it a journalist and came out a politician. The dispute dragged on for more than two months, with no movement on either side. He was dumbfounded by the indifference of John George Diefenbaker*’s government and of his English-speaking colleagues at the CBC, who boycotted the strike, considering it a revolt against Canada. Many people would say that this strike was a catalyst in Lévesque’s nationalistic development. Moreover, for the first time he had the experience of addressing large crowds, and became aware of his power over them. Once the dispute was settled, it seemed evident that television had become too small a world for him. Until then, he had asked the questions; from this time on, he would want to give the answers as well.

On 22 June 1960 Lévesque took the plunge, entering the political arena as a candidate in the riding of Montréal-Laurier, where he won by a narrow margin. Courted by the Liberals since his resignation from Radio-Canada in April, he had finally rallied to the slogan of their new leader, Jean Lesage*, “It’s time for a change!,” which prefigured the Quiet Revolution. The soundness and serious nature of the reforms proposed by the Liberals – free education, hospitalization insurance, a new direction in the economy, modernization of the state, and war on patronage – had persuaded him. He would soon assert himself as a star minister in the famous “fireball team,” which intended to bring the province into the modern era. This team, also baptized by the press as the “three Ls,” combined the three leading figures in the Liberal Party: Lesage, Lapalme, and Lévesque. The new premier, Lesage, initially gave Lévesque two portfolios, public works and hydraulic resources. At public works, convinced that it was possible to be a politician and remain honest, Lévesque attacked corruption, at the request of his leader, who had made it one of his priorities. More specifically, he attacked the system of patronage instituted by the former government of Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*. Henceforth, all government contracts for more than $25,000 would be tendered.

In March 1961 two ministries – hydraulic resources and mines – merged to become the ministry of natural resources. Lévesque would hold this portfolio until January 1966, but he left public works to René Saint-Pierre. A practical politician, Lévesque did not let ideology get in his way. If he counted primarily on the state as the lever of economic development, it was because French-speaking Quebecers possessed only one big business: their government. They had no true entrepreneurial class capable of combatting the province’s economic backwardness in certain sectors. He was of the opinion that electricity, which Quebec had in abundance, must become a public monopoly. It had been too hastily let go to foreign capitalists, who charged exorbitant and disparate rates, depending on whether one lived in Montreal or the Gaspé, and sent the profits out of the province. It must now be entrusted to the Quebec Hydroelectric Commission (or Hydro-Quebec), created in 1944 by the government of Adélard Godbout*, which had nationalized the Beauharnois Light, Heat and Power Company and Montreal Light, Heat and Power Consolidated to form the nucleus of Hydro-Quebec. What was needed for electricity to become the engine of the Quebec economy was the consolidation of its exploitation, which was divided at the time among 11 private companies that the government should nationalize. In 1962 Lévesque created an uproar by uttering for the first time the taboo word “nationalization.” He finally imposed it, despite the original refusal of Lesage, who was worried about its repercussions on the provincial debt.

The premier did indeed have a change of heart. He was outraged by the blackmail on the part of the Toronto and Montreal bankers, who not only refused to finance nationalization but threatened to have nothing to do with government loans if the administration took over the Shawinigan Water and Power Company. The argument that increasing the debt would drive the province into bankruptcy, put forward by George Carlyle Marler and other ministers opposed to nationalization, did not hold up. Douglas Henderson Fullerton, an independent financial expert consulted by Lesage, gave him a reassuring report. If Canadian moneylenders did not want to assist in underwriting nationalization, the Americans would be only too glad to do so, since the province’s debt was one of the lowest in the country. Lévesque got the same assurance from Roland Giroux*, a broker who had close ties to American financial circles. After the election, Lévesque would send him to New York with his advisers Michel Bélanger* and Jacques Parizeau* to borrow the money required to finance nationalization. As for the electrical companies, they had at last given in, confining their actions to raising the stakes with respect to the monetary compensation that the government planned to pay them. If Lesage finally stopped his shilly-shallying, it was also to reaffirm his leadership, which had been damaged by his indecision. There was no better way to re-establish unity than a surprise election he was certain to win, according to the opinion poll he had secretly commissioned.

On 14 Nov. 1962, in an election that was almost a referendum, fought under the slogan “Masters in our own house,” the voters gave their consent to the nationalization of the private electrical companies. The total cost, originally estimated at $600 million, would rise to $604 million. The loan negotiated in New York would come to $300 million. The nationalist fervour of the 1960s had worked in Lévesque’s favour. It had become inconceivable that huge foreign companies should exploit the province’s resources and then send most of their profits abroad. Besides, the advantages of nationalization had finally been made obvious. It was necessary to put an end to the waste caused by the overlapping of power lines and anarchy in the catchment areas, where private companies were stepping on each other, as well as to the varying rates being charged. The government would recover the taxes that companies had been sending to Ottawa. The Quebec economy would also benefit from the creation of a whole range of secondary enterprises in different regions. Last of all, Lévesque, whose charisma and persuasive powers were far from negligible, had had the support of the people and the press. He had also been able to count on the respect and admiration that Lesage still showed him.

Three years later, on 15 Oct. 1965, Lévesque would carry out an initial assessment of Hydro-Quebec. It had become the largest industrial enterprise in the province, with 17,000 employees and assets of $2.5 billion. It produced 34 per cent of Canada’s hydroelectric energy. Furthermore, this “colossus,” as the press called it, spoke French, both on the large construction sites and at its head office, where English had ruled absolutely until that time, even though a majority of the employees were French-speaking. Hydroelectricity became the field for training French-speaking managers and engineers, who had formerly been underestimated at the Shawinigan Water and Power Company.

Lévesque also discovered that the mining sector was simply a “branch” of foreign multinationals, which shipped ore to the United States, where factories transformed it into finished products. Since the province was satisfied with royalties that were among the lowest in Canada, the profits also ended up in foreign hands. The management and the expertise came from elsewhere. He also observed that there was no real policy on mining development. Convinced that the state had to play a role in exploring and exploiting its mineral resources, he undertook a radical revision of legislation on mining, which by now was more than 80 years old. Then, by forcing Lesage’s hand while the premier was under pressure from the big companies, he would create in 1965, with the support of his cabinet ally Eric William Kierans*, the Quebec Mining Exploration Company (SOQUEM). To ensure that the concessions would no longer lie dormant for years, the leases became revocable after ten years of inactivity. Last of all, he doubled the mining fees previously paid by the mining companies.

Long before the awakening of the First Nations, Lévesque was keenly interested in the aboriginal question. The Gaspé of his childhood was also the homeland of the Micmac, who were confined to their wretched reserves in Restigouche and Maria (Gesgapegiag), adjacent to New Carlisle. In the summer of 1954, as a reporter for Carrefour, he accompanied Prince Philip on a visit to the Inuit of Ungava Bay, and the discovery of their Third-World conditions left him feeling uneasy. In 1961, during a trip to New Quebec that he undertook as part of his portfolio as minister of natural resources, he rediscovered the almost prisonlike world in which First Nations people and Inuit were living. And he was distressed by the absence of French in the province’s northern latitudes. In the federal schools, neither French nor Inuktitut had any standing. This vast territory had been ceded to Quebec in 1912, but its governments had allowed Ottawa to move in with its schools, its health clinics, and its civil servants, all of which served to anglicize the aboriginals.

Determined to recover authority over New Quebec and its inhabitants, Lévesque came up against the refusal of the federal minister of northern affairs and national resources, Arthur Laing, who held back the transfer by claiming that the Inuit did not want to speak French. At the end of May 1964, in Winnipeg, Laing maintained that Ottawa had to keep control of education, health, and welfare, “in order,” according to the Montreal daily Le Devoir (30 May), “to preserve the rights of Eskimos as first-class citizens.” A furious Lévesque retorted that the minister’s fears “were inspired by political considerations and hypocrisy.” When Laing told the House of Commons he doubted Lévesque’s sincerity, the latter reminded him that Quebec was the only province in Canada that had set an example, since confederation, of respect for the linguistic and religious rights of the minority. The Toronto press, for its part, attributed “territorial ambitions” to Lévesque, according to the title of an article by Blair Fraser* in Maclean’s on 16 May 1964, and even separatist designs. Nevertheless, the territory in question belonged to Quebec and the Inuit population, who, not being considered “Indian” by the federal government, were not covered by the Indian Act. Even worse, in Lévesque’s eyes, was the fact that the neighbouring province of Newfoundland had been governing Inuit there since entering confederation in 1949. He was exasperated by this double standard and the words being put into his mouth. According to Fraser’s report, he warned: “This Ungava issue is a test case of federal-provincial co-operation. If we can’t even settle this, we can’t settle anything.” Common sense would finally prevail, thanks to the direct involvement of Prime Minister Pearson and Premier Lesage. During his term as federal minister of northern affairs and national resources, from 1953 to 1957, Lesage had not concerned himself with the question, but now he fully supported Lévesque’s claim. Although he occasionally toned down his minister’s aggressive behaviour, he nevertheless suggested to Pearson that he bring Laing into line and demanded, at the federal-provincial conference held in November 1963, that the transfer of jurisdiction be put into effect before 1 April 1964.

A few years later the New Quebec that Lévesque had known in the 1960s, with its unsanitary shacks lacking electricity and heating, would become unrecognizable. Electricity and heated dwellings would be the norm. But in addition the city of Kuujjuaq would have a hospital, a secondary school, an arena, and an administrative centre. Lévesque had had a hand in this result. By putting the north under his protection, he had stimulated intergovernmental innovation and competition in the fields of education, health, and the economy.

In October 1965 there was a surprise cabinet shuffle. The pendulum of Liberal reform swung from the economy to social policies. Lévesque left the natural resources portfolio for that of family and social welfare. The world of the underprivileged was familiar to him. On Saturday mornings, his riding office was crowded with ordinary individuals asking to see “René.” Lévesque himself had the natural humility of common people. His first objective was to put through one single law on social assistance, centred on the family. He tackled the problem of adoption, which he wanted to make more humane, got approval for free medical assistance to the poor, increased the allowances for unmarried mothers, and prepared a white paper on handicapped children. At the Ottawa conference held in January 1966, convinced that social security ought to come from the provincial government, he demanded – unsuccessfully – the return of responsibility for family allowances. Thanks to this last trial of strength with Ottawa, and the earlier one that had pitted him against Laing, Lévesque took the measure of Canadian federalism, which seemed to him to have been hardening with respect to Quebec’s demands since the arrival of Pierre Elliott Trudeau* in Ottawa following the November 1965 election. In February 1969 he would admit, in an interview with Jacques Guay of Le Magazine Maclean (Montréal): “[As for] me, I already no longer thought it possible that a federal state would agree to cut off a limb. As I watched the files and the conflicts with Ottawa multiply, I became, without daring to admit it to myself, more and more of a sovereignist.”

On 5 June 1966 his party’s defeat at the polls forshadowed the end of Lévesque’s political career as a Liberal. Stripped of power, he had the impression that he was staring into a void and was not too sure what to do with his future. Having been re-elected in his riding, his only immediate certainty was that he would complete his four-year term as a backbencher. After that, he would see – perhaps he would go back to journalism, but nothing was less sure. Lévesque rethought his political affiliations in a Quebec caught up in the fever of protest that was sweeping the western world. Pacifists were denouncing the war in Vietnam, students were occupying campuses, partisans of independence were chanting “Le Québec aux Québécois,” supporters of the Union Nationale were demanding “Égalité ou Indépendence” as their leader Daniel Johnson* – now premier – had written in his book published in Montreal in 1965. In July 1967 Charles de Gaulle, the president of France, unleashed his famous “Vive le Québec libre!” from the balcony of Montreal’s city hall. And then there was the Front de Libération du Québec, which was setting off its bombs.

Previously, when Lévesque was asked whether he was a nationalist, he would hesitate, still haunted by his memories of the war. Though he was a nationalist in his own way, the question would always make him uneasy. In 1948 he had written in the staff magazine of Radio-Canada’s international service: “I am for all practical purposes a Quebec nationalist, a perfect Laurentien.” In fact, what left him cold was traditional French Canadian nationalism, with its “Frenchifying gimmicks, bilingual cheques, the flag,” as he would put it in 1969 to Le Magazine Maclean. Lévesque, who peppered his remarks with tangible examples that inspired confidence, displayed a practical nationalism. If he made a reference to the massive dam on the Rivière Manicouagan, it was to suggest to French-speaking Quebecers that they were capable of great things. He would never be a flag waver, fearing the politics of the street with its ever-present potential for emotionalism and brutality. This was the reason why he was constantly at odds with the Rassemblement pour l’Indépendance Nationale, whose direct action, verbal violence, and chauvinistic language repelled him. Nevertheless, in the June 1966 election, when that party was running candidates, he was troubled. Since Pierre Bourgault*, then the leader of the RIN, had moderated his words and given a social-democratic flavour to his political position, Lévesque had the impression that he was fighting against a fraternal party.

Earlier, on 27 February, Lévesque had made it clear that the aim of nationalism, as he was trying to live it out, was to abolish the privileges, not the rights, of the English-speaking minority. He confirmed in his memoirs: “I am a nationalist … if that means being for oneself, fiercely for oneself – or against something … against a given situation. But never against someone.” He saw this “situation” more clearly after six years of political struggles. The Quiet Revolution was only a beginning. Quebec had to go further to free itself from the economic yoke it had laboured under for too long, and from a federal regime that had hardened after the first years of the decade, when there had been a more obvious willingness on Ottawa’s part to cooperate with the provinces. The acceleration of Quebec nationalism during the 1960s left its mark on Lévesque. Even though it was not really a question of conversion, he had been throwing around, especially since 1963, incendiary phrases that bore witness to his radicalization. During a stop in Toronto at the end of May 1963, he admitted to television interviewer Pierre Berton* that he would not shed many tears if Quebec separated. On 5 May 1964 Le Devoir’s headline on the report of his visit to Timmins, Ont., stated that, according to Lévesque, “better separation than constant quarrelling.” On 9 May, speaking to the students at the Collège Sainte-Marie in Montreal, he declared that the only appropriate status for Quebec was that of an associate state, a status which would have to be negotiated with the rest of Canada “without rifles and without dynamite as far as possible.… If Quebec is refused this status, we will have to separate,” Le Devoir noted two days later. According to the Montreal Star of 20 Feb. 1967, he warned his listeners in western Canada: “Either Quebec gets a new deal [with the rest of Canada] or eventually it will get out.”

During the summer of 1967, after carefully weighing all the factors, Lévesque concluded that the country had become a “madhouse,” and that the future lay somewhere else than in this federal Canada, which he rejected, and of which Trudeau had become the champion ever since his election to the House of Commons in 1965. “We are Québécois,” he declared in the manifesto he issued first to his supporters in the riding of Laurier on 18 Sept. 1967. (A slightly amended version would be published in Montreal the following year.) The title, Option Québec (published as An option for Quebec, Toronto, 1968), summed up its basic idea. At the age of 45, Lévesque chose to struggle henceforth for a Quebec homeland. By doing this, he assumed the role of fraternal enemy to Trudeau, his ally of the 1950s, when they and a handful of others comprised the informal opposition to the Duplessis government. When the Quiet Revolution made its first proclamations, they were in agreement on many things: a larger role for the state in education, the economy, and social affairs; the modernization of Quebec; and the democratization of its political life. But the conflict of personalities was never far below the surface. The nationalization of private electrical companies was one of the subjects on which they took opposite stands. Their relationship, never easy, was finally overwhelmed by the flood tide of the new nationalism. Just a few short months later, in April 1968, Trudeau would become prime minister of Canada. A battle of titans broke out between two strong leaders who had irreconcilable visions of their province’s future.

In October 1967 the convention of the Quebec Liberal Party opened in an atmosphere of hostility, which became contagious as soon as the party’s former star took his seat. The wind had changed. Lesage and Kierans, who had worked closely with Lévesque during the good years of Liberal reform, sealed his fate by threatening to resign if his ideas were supported by the delegates. Nevertheless, Lévesque tabled his resolution, “A sovereign Quebec within a Canadian economic union,” inspired by his manifesto. Quebec would no longer be a province but a sovereign state, levying taxes, passing laws, and dealing with other nations in its own name and its own language, but would associate with Canada at the economic level. Unable to convince his Liberal comrades-in-arms, Lévesque withdrew his resolution before the show of hands that would take place, nonetheless, after his departure. He announced that he would do his best to promote it elsewhere. Then, followed by a handful of supporters, he left the hall. From then on, the rebel would sit in the Legislative Assembly (renamed National Assembly the following year) as the independent member for Laurier, while preparing to launch his own party.

For some, Lévesque was now a heroic figure; for others, he was public enemy number one. With 400 adherents one month after his resignation, the group that would become the sovereignist party had grown to 2,000 by January 1968. On 19 April, at the founding of the Mouvement Souveraineté-Association, from which the Parti Québécois would be born, the membership had climbed to more than 7,000. From the moment the MSA was founded, Lévesque kept the future party from becoming sidetracked into political marginalization. He had to threaten to go home to win respect for the educational and linguistic rights of the English-speaking minority, which were contested by the faction within the movement that identified with the RIN. Lévesque gauged the fragility of his leadership and distinguished more clearly the various groups, often opposed to each other, that made up his new political family: former Liberals, the separatist followers of Bourgault (who would himself scupper the RIN), social-credit supporters from the Ralliement National, left-wing trade unionists with socialist leanings, and a multitude of students. Half of the delegates were under the age of 30. The founding convention of the PQ on 11 Oct. 1968, unlike that of the MSA, proceeded harmoniously. The PQ’s program would be similar to the one sketched out in the spring by the delegates of the MSA: French as the only official language, recognition of the rights of the minority, a unilateral declaration of independence, a presidential system, compulsory trade-union membership, an interventionist state that would yet respect free enterprise, territorial integrity, the recovery of Labrador, and withdrawal from military alliances such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

But before reaching the paradise of power, there was the desert to cross. Between 1966 and 1976, Lévesque led a rather Spartan existence. Until his personal defeat in the election of April 1970, he had drawn his salary as an mna. That summer he left Louise L’Heureux and went to live with Corinne Côté, a teacher from Alma. Lévesque could not rely on his mna pension since he was sending it to his wife, who was raising their three children. Fortunately, he had some income from his work as a journalist. Back in September 1966 the Montreal periodical Dimanche-Matin had commissioned him to write a weekly column, but he gave it up in 1969, shortly before the 1970 election. After his defeat in Laurier, Le Journal de Montréal in turn made him an offer of $200 a week. Lévesque had always refused to take a salary as leader of the PQ, but in February 1976, after the indépendantiste Montreal daily Le Jour ceased publication, depriving him of his income as a columnist, the party paid him $18,000 a year.

The PQ solicited votes for the first time on 29 April 1970 in a provincial election dominated by the fear of separatism fanned by the new Liberal leader, Robert Bourassa*, and by the intervention of the federal Liberals, who published in Montreal, in their internal newsletter What’s New?, a study purporting to show the benefits of federalism for the people of Quebec. The figures were so far-fetched, however, that Bourassa and Trudeau disowned the study. Bourassa’s promise to create 100,000 jobs, a key theme in Quebec where there was a high level of unemployment, also weighed heavily in the outcome of the voting. Defeated in the riding of Laurier, Lévesque succeeded in getting only seven members elected, even though his party received 23.1 per cent of the votes. That year the October crisis proved disastrous for his political position. The FLQ had kidnapped James Richard Cross, a British diplomat, and Pierre Laporte*, the provincial minister of labour and manpower, as well as of immigration, who would be found murdered on 17 October. To overcome the FLQ, Trudeau, under pressure from the Bourassa government, toyed with the idea of proclaiming the War Measures Act. On 14 October, in collaboration with Claude Ryan*, the publisher of Le Devoir, Lévesque brought together leaders from different social spheres, including Louis Laberge*, president of the Fédération des Travailleurs du Québec, Alfred Rouleau, future president of the Desjardins movement, and sociologists Fernand Dumont* and Guy Rocher. The objective of the 16 signatories to a common declaration drawn up by Lévesque was to encourage the governments to abandon strong-arm tactics and negotiate with the kidnappers to save the lives of the hostages. Their appeal was not heeded, however. On 16 October Ottawa proclaimed the War Measures Act, giving it sweeping emergency powers [see Trudeau]. By the next day some 40 members of the PQ had been arrested. In Lévesque’s view, this was an extreme and anti-democratic measure that violated the centuries-old British tradition of habeas corpus. Associated with the FLQ by its opponents, the PQ lost 45,000 members who would no longer risk describing themselves as “péquistes.”

Repudiated by public opinion, the PQ was a victim of illegal espionage by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. During the night of 8 Jan. 1973 RCMP agents broke into a building and stole the party’s membership list in what has become known as Operation Ham, as would be disclosed in the reports of inquiries by Judge David C. McDonald (1979–81) in Ottawa and Commissioner Jean F. Keable (1981) in Quebec City. Lévesque would accuse the Trudeau government of wanting to take advantage of the extremes of FLQ terrorism to strike a death blow to his party.

Lévesque’s handicap at the polls was still the same: people were afraid of sovereignty. Having shifted to the PQ in May 1972, Claude Morin, who had been deputy minister of federal-provincial affairs and intergovernmental affairs in the administrations of Lesage, Johnson, Jean-Jacques Bertrand*, and Bourassa, persuaded Lévesque to hold a referendum before making any declaration of independence. But Premier Bourassa called a snap election before Lévesque had a chance to get the idea accepted by the followers of economist Jacques Parizeau, who favoured independence with no referendum and no obligatory association with the rest of Canada. On 29 Oct. 1973 the Liberals won a landslide victory. Lévesque, who ran in the riding of Dorion, suffered personal defeat for the second time and lost one of the seven members elected three years earlier. All was not doom and gloom, however. The sovereignist vote increased from 23.1 to 30.2 per cent, and reached nearly 40 per cent among francophones. Furthermore, the PQ became the official opposition, led by an influential new member, constitutional expert Jacques-Yvan Morin. The Liberal Party elected 102 members, thanks to a not-very-democratic voting system that gave 5.5 per cent of the seats to the party that had won 30.2 per cent of the popular vote.

Lévesque wondered whether he was still the right man for the situation. He wanted to call it quits and do something else with his life. In Quebec City, his six National Assembly members were left on their own. Soon his lack of interest in the party led to grumbling. As the November 1974 convention drew near, he agreed, at the urgent request of his entourage, to stay at his post, but on his own terms. He was determined to bring to heel those who were eroding his authority by means of the debate on the need to hold a referendum before declaring independence. At the gathering, which has gone down in history as the “step-by-step” convention (because of the idea of “étapisme” attributed to Morin), Lévesque had the word “referendum” written into the program. In early September 1976 he put down the rebellion of mnas Robert Burns and Claude Charron, who were calling into question his leadership.

With peace restored, Lévesque began confidently and calmly to prepare for the fall’s election campaign. He had turned 54 on 24 August. He seemed more relaxed, less aggressive. His love life had become more stable now that he was living with Corinne Côté. For a pro-independence party, the prospects of coming to power had never been so good. Lévesque expected to win a minimum of 35 seats and, if luck was with him, to form a minority government. The proposal adopted at the 1974 convention – to hold a referendum conditional on the attitude of the federal government – now gave way to a clearer electoral promise: there would be a referendum before the end of the first term of office.

Lévesque was facing a government worn down by six years in power and discredited by patronage, political interference, and conflicts of interest in the Quebec Liquor Corporation and the Société d’Exploitation des Loteries et Courses du Québec (revealed by the commission of inquiry into organized crime). Bourassa was also facing accusations of nepotism. Moreover, the premier was deluding himself by thinking that he would achieve victory by using Ottawa as a whipping boy. When Trudeau had come to him in the spring seeking support for his plan to repatriate the British North America Act of 1867, Bourassa had refused. Trudeau had then threatened to proceed unilaterally, thereby giving Bourassa a pretext for calling an early election. Last of all, the fragility of the Liberal government was partly due also to the Official Language Act (also known as Bill 22), which, among other things, had proclaimed French as the official language of Quebec, but divided the English-speaking voters who traditionally supported the Liberals. Yet it was not so much the proclamation of French as the official language that had outraged anglophones, but rather the linguistic tests imposed on children who wanted to enrol in an English school. They were afraid that these tests would keep immigrants and francophones out of their schools. Lévesque, for his part, saw the act as an arbitrary and odious measure that opened the door to discrimination between different ethnic groups. Above all, Bill 22 did not deal realistically with the question of getting immigrants to acquire the French language.

On 15 November the PQ caucus increased from 6 mnas to 71 and the Liberal Party dropped from 97 to 26. To Claude Morin and some analysts, Lévesque owed his victory above all to having downplayed sovereignty during the campaign and having promised to hold a referendum. Be that as it may, his determination to introduce political transparency and good government (as the saying goes) also persuaded a majority of voters. Lévesque had accomplished the tour de force of not only rallying his customary electoral supporters – trade unionists, students, teachers, intellectuals, young people – but also making a breakthrough into circles that had previously rejected his message, such as small shopkeepers, mayors of villages and small towns, women, the elderly, farmers, and even military personnel. Unlike anglophones who had revived the moribund Union Nationale rather than cast their votes for the PQ, immigrants had proved much more receptive. History took an abrupt turn. For the first time, a party that proposed to break up confederation would form the government of Quebec. Prime Minister Trudeau, half-heartedly congratulating the winner, warned him that he would never negotiate the partition of Canada.

Lévesque would hold power for two terms, 1976–81 and 1981–85. For support, he called on a team of 18 ministers, 5 of whom held two portfolios, with a total of 23 ministries. Some of them had impressive credentials and were graduates of elite schools: Jacques Parizeau (London School of Economics and Political Science), Jacques-Yvan Morin (Harvard University and University of Cambridge), Claude Morin (Columbia University), Yves Bérubé (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), and Bernard Landry (Institut d’Études Politiques de Paris). Others, like broadcaster Lise Payette, brought qualities such as celebrity status, vivacity, and charisma that were sometimes missing in those who shone by reason of their education and experience. Lévesque would need all these abilities to turn around both the financial management of the province and the economy. Public services were more costly in Quebec than anywhere else in Canada. A family of four in Quebec paid $1,000 more in taxes than a comparable family in the other provinces. The economic growth for his first year in power would be lower than that of the country as a whole, while unemployment would rise to 9.5 per cent. Far from being paralysed by these sombre prospects, the new government, on its election, set in motion a huge wave of reform harking back to that of the 1960s. These changes would radically alter Quebec society. First of all, Lévesque could finally achieve his goal of political transparency; he pushed it to the limit by banning secret electoral funds and replacing them in 1977 with a system of public financing for political parties. As the victim of a system that created an imbalance between a party’s real strength and its representation in parliament, he began to redraw the electoral map, which gave up to six times as much weight to the rural vote as to the urban, and change the electoral system, which similarly created an imbalance between the percentage of votes and the number of seats. He introduced elements of proportional voting, but could not complete this last reform because of the solid opposition of his mnas. Relying on the public’s hostility to proportional representation and feeling threatened by the complexity of proportional voting, most of them also saw such a reform as a source of political instability, which would make it difficult, for instance, to pass controversial bills. On 23 June 1978 Lévesque would as well put through the Referendum Act, which was to govern the holding of a referendum.

During the election campaign, Lévesque had promised to make Quebec as French as Ontario was English. In his view, however, law and language were not a good match, as he had warned Premier Bourassa when the latter had proclaimed the Official Language Act in 1974. Moreover, he said openly that he found it humiliating to have to resort to legislation, since only a downtrodden and colonized people must brandish the law to impose their language. But the decline of French, especially in Montreal, the massive anglicization of immigrants, and the demographic and linguistic context of North America, where the ratio of French-speaking Quebecers to non-francophones was one to forty, threatened the survival of a French Quebec.

In Lévesque’s opinion, it was not a question of scrapping the Official Language Act in order to give birth to a new “Magna Carta” of language for general edification. He simply wanted to modify it in order to give back to francophones a useful enjoyment of their language at work, in signage, in business, and in public administration, and to get immigrants to acquire the French language. But Camille Laurin*, the influential and persuasive minister of state for cultural development, acting on the advice of sociologists Rocher and Dumont, took him further than he wanted to go. Proclaimed and put into force on 26 Aug. 1977, the Charter of the French Language, commonly known as Bill 101, declared Quebec a unilingual society and excluded English from the legislature and courts in violation of article 133 of the Canadian constitution, which guarantees the use of both languages. (This part of the Quebec law would be struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada in December 1979.) Moreover, the law made English schools available only to children whose parents had studied in English in Quebec. This is the “Quebec clause,” as opposed to the “Canada clause” favoured by Lévesque, which would have opened English schools to the children of all English-speaking Canadians. According to Dr Laurin, on 1 April 1977, the day before he tabled his white paper in parliament, the premier carelessly remarked to him during an emotional tête-à-tête: “I can’t say that I like your law, doctor. I have to pass it because we are not free. I can’t prevent immigrants from coming to our province, but if I do nothing, they will become anglicized and dispossess us. I have no choice. If we lived in a normal country, doctor, we wouldn’t need your law.” Though he finally accepted the Quebec clause, he did so also because he was gambling that the English-speaking provinces with a French-speaking minority would adopt the reciprocity he had offered them. Under this arrangement, anglophones from a province that granted its minority the same access to schools as was granted by Quebec to its English-speaking minority could enrol their children in English-language schools in Quebec. If this reciprocity were to be accepted by the English-speaking provinces, it would effectively cancel the Quebec clause. In cabinet, Lévesque could not oppose the bill’s article on the language of instruction without running the risk of finding himself in the minority. This text – which would become the law that would have the greatest effect on the face of Quebec and the mentality of its people – enjoyed solid support among the public, party members and mnas, and in the cabinet. This was far from being the case among anglophones, more than 130,000 of whom would choose to emigrate between 1976 and 1981, mostly to Ontario. Similarly, motivated by the westward shift of their financial activity, a number of large companies, such as the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, a multinational that did 80 per cent of its business outside the province, would move to Toronto, giving Bill 101 as the reason.

To end Quebec’s first-place standing for the greatest number of road accidents, the lowest compensation for claims, and the highest insurance premiums in Canada, and to correct a situation where one Quebec vehicle in five had no insurance, Lévesque introduced the system of public and compulsory automobile insurance advocated in 1974 in the Report of the committee of inquiry on automobile insurance. This study had been done under Jean-Louis Gauvin as chair and commissioned by the Bourassa government, which later shelved it. The Act to establish the Régie de l’Assurance Automobile du Québec and the Automobile Insurance Act, both of which took effect in March 1978, were unpopular pieces of legislation. The complicated new system required a driver to carry two forms of insurance, a public one for personal injury regardless of liability (which some ministers complained would absolve drivers of responsibility), and a private one for property damage (which, it was believed, would further increase the cost). Moreover, the reform caused an outcry among lawyers and insurance agents close to the PQ, who saw their livelihood being taken away from them. Under pressure from lawyers, who were well represented in the cabinet, the government was divided. The legislation crossed the finish line only with Lévesque’s decisive support for Lise Payette, the minister of consumers, cooperatives, and financial institutions.

According to Lévesque and his minister of agriculture, Jean Garon, Ottawa was favouring the big grain and cattle farms in the western provinces, while confining Quebec to dairy farming. This policy stood in the way of Lévesque’s determination to diversify Quebec agriculture to develop the food-processing industry and agricultural self-sufficiency. On 22 Dec. 1978, to curb financial speculation, he had the Act to preserve agricultural land proclaimed (which in its effects was retroactive to 9 November).

As well, Quebecers’ entrepreneurship emerged in the economy. In 1978 Parizeau, the finance minister, abolished the eight per cent sales tax on everyday consumer goods to assist low-income families while also helping the vulnerable sectors of the economy – textiles, furniture, footwear, and clothing. In 1979 he introduced stock-savings plans to initiate Quebecers into the stock market and at the same time create a reserve of local capital for small and medium businesses. Along the same lines, the government set up the Program to Stimulate the Economy and Uphold Employment (1977), adopted a policy of preferential purchasing (1978), and published in 1979 a strategy for economic development, Bâtir le Québec….

On the social front, Lévesque brought in a long list of measures that showed the social-democratic orientation of his government: free medicine for the elderly (1977), the Youth Protection Act (1977), therapeutic abortion (1977), the Act to secure the handicapped in the exercise of their rights (1978), and the Act respecting child daycare (1979). On the labour front, the government had a law against strike-breaking passed (1977), promoted labour-management dialogue by organizing the economic summit at La Malbaie (1977), and had the Act respecting occupational health and safety given royal assent (1979). In the field of culture, in addition to the Charter of the French Language and the creation of maisons de la culture, the Act to incorporate the Société Québécoise de Développement des Industries Culturelles was assented to in 1978. Justice minister Marc-André Bédard, for his part, dusted off and democratized the administration of justice, set up the Commission Québecoise des Libérations Conditionnelles, and instituted class-action suits that year. Lévesque also provided the province with a policy on scientific research (1980). To put an end to the grip of U.S. corporations on Quebec’s asbestos, which was being sent out of the country to be processed, he tabled Bill 121, authorizing the government to nationalize the Société Asbestos Limitée in 1978. Protracted judicial skirmishes with the American company began, which would go on until 1982. In the meantime, asbestos fibre would be declared carcinogenic, and the industry collapsed. The beautiful dream would cost the taxpayers $435 million.

In foreign policy, Lévesque pursued two main objectives. Following the example of premiers Lesage and Johnson, he sought to maximize Quebec’s visibility in the world by developing more and more contacts with other countries, whose sympathy would be useful if ever the people of Quebec authorized him to form a new country. The second pillar of his foreign policy was based on his determination to deal directly, in his own name and without a federal chaperone, with foreign dignitaries and heads of state. This policy brought him into conflict with Ottawa, which was jealous of its international sovereignty, and occasionally led to embarrassing situations. In January 1977, at the Economic Club of New York, where only the Quebec fleur-de-lys flag was flown beside the star-spangled banner, Lévesque tried to reassure the 1,600 guests – mostly American moneylenders and investors – about the security of their investments in Quebec. Since he spent almost his entire speech drawing a bold parallel between the independence of Quebec and that of the American colonies 200 years earlier, it was a “monumental flop,” as he would write in his memoirs. He made up for this failure in November of that year, during an equally sensational official visit to Paris. The French president, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, and his prime minister, Raymond Barre, welcomed him with all the show of respect due a real head of state, and not like an ordinary provincial premier, as Ottawa had insisted. But Ottawa was less worried about the thickness of the red carpet than about Lévesque’s determination to give Franco-Quebec dialogue a more political dimension. The creation of an annual summit meeting between the French prime minister and the premier of Quebec confirmed Canada’s fears, especially since the prime ministers of France and Canada did not meet once a year. Besides, placed on the same footing as the prime minister of a sovereign country, with complete authority, Lévesque, an ordinary provincial leader, might raise topics that went beyond Quebec’s jurisdiction. Ottawa would not rest until it had made Paris back down on the matter. And so, in February 1979, to lessen the impact of the first Franco-Quebec summit, which was held that year in Quebec City, Prime Minister Trudeau insisted that Barre should go to Ottawa first.

This visit gave Lévesque the opportunity to make clear his intentions with regard to Corinne Côté. Their liaison had become public on the night of 5 Feb. 1977, when Lévesque, with Corinne in his car, had accidentally run over a homeless man lying in the street. In September 1978 he had obtained his divorce from Louise L’Heureux. The presence of the young woman beside the premier of Quebec, on the occasion of a reception in honour of Barre and his wife, annoyed the French couple. In Paris a mistress is not among the invited guests. Power had not changed Lévesque in the slightest. Rebellious as ever, he sometimes refused to conform to the constraints that protocol placed on his office. He still smoked as much in front of the camera, and he wore short-sleeved shirts and, invariably, sports shoes, the eternal “Wallabees” that amused the press. He smoothed things over by confiding to his guests that Corinne Côté was his fiancée and they would be married in April – as indeed they were, at a private ceremony on 12 April 1979.

In this year preceding the referendum, however, Lévesque’s greatest challenge was to convince a majority of Quebecers to follow him all the way to independence. It was the battle of his life. During the 1976 election campaign, he had promised to hold a referendum before the end of his first term of office. On 1 Nov. 1979, despite unfavourable polls, he tabled in the National Assembly the white paper on sovereignty-association, which offered the rest of Canada a new agreement between two peoples, politically sovereign, but economically associated: Québec-Canada, a new deal: the Québec government proposal for a new partnership between equals, sovereignty-association. The document emphasized both Quebecers’ desire for autonomy and the deadlocked federal system, and it proposed to take back all powers and taxes within the framework of a new association, more economic than political, between two sovereign states. Provincial civil servants, who were more concerned about their working conditions, which they were in the process of negotiating, than about the outcome of the referendum, disrupted the event by singing O Canada before smashing windows and shutting the journalists in the press room. The situation became more complicated at a cabinet meeting on 19 Dec. 1979. The adoption of a complex and rather long referendum question created divisions among the ministers. The question included a request for a mandate to negotiate a new agreement with the rest of Canada, as well as the idea adopted at a convention the previous June of a second referendum (to consult the people on the results of discussions with the federal government following the first referendum). Some ministers, including Denis Lazure* and Lise Payette, went home early in the evening, convinced that the premier would get what he wanted, even at some cost to Parizeau. The finance minister’s opposition to what he considered the bizarre idea of a second referendum was flagging as time went on. Lévesque had to use all his authority to bring him into line. At the National Assembly the next day, he seemed to be troubled by the premier’s reading of the question. He hurried out of the room, convinced that the definitive wording was not the one accepted the day before. In fact, Lévesque had forgotten to inform him of some minor changes introduced afterwards by the lawyers. Being suspicious by nature, Parizeau had had immediate doubts, but revised his position after further consideration.

Lévesque had foreseen everything but the return of his eternal political rival, Trudeau. The Liberal leader, who had been defeated by Charles Joseph Clark’s Conservatives in the election of 22 May 1979, resurfaced in December after the Conservative government fell. On 18 Feb. 1980 Trudeau was re-elected, just in time for the referendum. On 20 June of the previous year Lévesque had reached a decision: the referendum would be held in the spring of 1980. He made this decision public the next day, but without specifying the date – 20 May 1980 – which he would divulge to the National Assembly on 15 April 1980. On 4 March the leading lights of the government had begun a 35-hour parliamentary debate on the referendum question that went on until 20 March. The confrontation, which was won hands down by the government, gave the Yes camp a slight lead. Indeed, for the first and only time, according to an internal poll conducted by the party, the PQ speakers had more than 58 per cent of the votes, and Ryan’s No camp just 12 per cent. Put at a disadvantage by subsequent negative polls, a strategy with no clear direction, an overly bureaucratic organization, and unmotivated party members, Lévesque’s campaign did not get off the ground. Moreover, Lise Payette, minister of state for the status of women, made women angry when she compared Ryan’s wife, Yvette, to a housewife living in the shadow of her husband. The “Yvette” movement in support of the No side caught fire and crippled the sovereignists, who were also hard put to counter the campaign led by the federal minister of justice and attorney general, Jean Chrétien, a campaign Lévesque considered illegal and immoral. The minister, without hesitation, disregarded the law on popular consultation, which, among other things, limited the spending of the two sides, and he had federal cheques being mailed out to Quebecers sent with slogans favourable to the federalist camp. The final blow came from Prime Minister Trudeau, who, in a few sentences and with a few promises, shattered Lévesque’s dream. Since Lévesque had stumbled earlier by emphasizing Trudeau’s middle name, “Elliott,” which recalled his mother’s Scottish ancestry (just as Trudeau himself had stumbled during the 1976 election by evoking the victory “of the blood brothers” to distinguish the francophones who had voted for the PQ from the anglophones and allophones who had supported the Liberals), the prime minister made a point of shouting out that his “name is a Quebec name.” On 14 May, shortly before the vote, Trudeau promised to resign if federalism was not renewed to the satisfaction of Quebecers. In so doing he gave the undecided voters a reason for voting No.

On 20 May Lévesque suffered the bitterest defeat of his political career. The surveys had left him no illusions, but he had hoped to win a majority of the francophone vote. He did not get it and had to be satisfied with a total of 40.4 per cent of the votes. He concluded that the people of Quebec were not yet ready for independence. It was hard for him to understand, however, that it was possible to say no to oneself. He was not asking for a mandate to separate, but for a mandate to negotiate a new agreement with Canada. Those around him would criticize him for having waited too long to hold the referendum, for having given his adversary, doubly decapitated by the departure of Bourassa and the defeat of Trudeau, a chance to recover. In the opinion of former premier Bourassa, the referendum was Lévesque’s most serious political error, for he had held it knowing that he would lose, thereby opening the way for Trudeau, who was burning with desire to repatriate the constitution without taking account of the province’s demands. In Lévesque’s view, the referendum had at least given judicial legitimacy to Quebecers’ right to self-determination. By participating in the popular consultation, Ottawa had accepted, at the international level, the idea that it was the people of Quebec who should determine their future, not Ottawa and not English-speaking Canada. Politically weakened and brought back to his role as a provincial premier, Lévesque put his struggle for a Quebec homeland on the back burner. He got down to the business of patching up the time-worn 1867 document, adopting the demands of his predecessors: equality between francophones and anglophones, constitutional recognition of Quebec’s distinct character, and a new sharing of powers between Ottawa and the provinces.

The ball was now in the federalists’ court, Lévesque had declared on the evening of his defeat. Trudeau caught it on the fly and invited him and the other premiers to join him in negotiating a new federalism. At the constitutional conference held in Ottawa in September 1980, the prime minister insisted on repatriating the constitution and enshrining within it a charter of rights and freedoms before really dealing with the actual question of the new sharing of powers demanded by a majority of the provinces. Matters came to an impasse, and to resolve it Trudeau threatened to proceed without the premiers’ agreement. On 6 October he presented a motion in the House of Commons for a unilateral repatriation of the constitution, including in particular an amending formula that gave all provinces the right to oppose any change in the constitution they considered unacceptable. But this veto would be valid for only two years following repatriation, after which the provinces and Ottawa would have to agree on a new formula, to be worked out. On 12 Nov. 1980 Lévesque presented his own motion in the National Assembly, opposing the federal “power grab,” which required unanimous agreement to be adopted. The opposition of Liberal leader Claude Ryan led to its defeat. This did not prevent Lévesque, in the course of the following winter, from building a common front against Ottawa, consisting of eight provinces, excepting only Ontario and New Brunswick, the two declared allies of the federal government. On 12 March 1981, in the midst of these negotiations, he decided to go to the people. His political acumen told him that the people of Quebec, worried by Trudeau’s threats (as Lévesque’s own polls showed), would elect him rather than Ryan, who had made the mistake of associating himself with the federal government in blocking the adoption of Lévesque’s motion against unilateral repatriation. His slogan was “We must remain strong in Quebec.” With the focus of the campaign on the accomplishments of his “good government,” the election of 13 April 1981 took on the appearance of a plebiscite. The PQ won two-thirds of the seats. On 16 April the eight provinces reached agreement on a plan for constitutional reform, which they intended to submit to Trudeau. To facilitate the agreement, Lévesque had to give up Quebec’s traditional right to a veto, in favour of the right to opt out and receive financial compensation.

On 28 September the Supreme Court of Canada, which in April had been called on for its opinion about the legality of unilateral repatriation, ruled partly in favour of Ottawa. Repatriation was legal, but would be un-constitutional in the “conventional sense.” There was an emergency session in Quebec City, where Lévesque put through, on 2 October, a motion of resistance which this time got Ryan’s support. Early in November, along with cabinet ministers Allan Joseph MacEachen and Jean Chrétien, as well as his personal advisers, Trudeau welcomed the provincial premiers to “the one last time” conference in Ottawa. On his side, Lévesque was accompanied by Claude Morin, the man in charge of the Quebec strategy, and two ministers, Marc-André Bédard and Claude Charron. There were some who felt that this was not a winning team, that it should have included ministers with a more solid grasp of constitutional matters and federal-provincial relations, such as Jacques-Yvan Morin and Jacques Parizeau. Of the ten or so subjects discussed at the previous constitutional meetings, there were only three left: the repatriation of the constitution, the amending formula, and the charter of rights – Trudeau’s three priorities. Brilliantly manipulated by Trudeau, Lévesque fell into the trap of a so-called Quebec-Canada alliance focused on the idea of an all-Canadian referendum on the constitution, something that the English-speaking provinces, who felt betrayed by Lévesque, wanted nothing to do with. Already showing cracks as a result of the Supreme Court decision and the desire of the premiers of the English-speaking provinces to reach an agreement with Ottawa, the united front of the provinces imploded. On the last morning of the conference, Lévesque was presented with the text of an agreement negotiated the evening before by three ministers, Chrétien (for the federal government), Roy John Romanow (of Saskatchewan), and Roy McMurtry (of Ontario), for which they had previously obtained the approval of the seven other provincial premiers. It was now Lévesque’s turn to feel betrayed by his former allies of the common front, whose nocturnal secret negotiations would go down in history as the “night of the long knives.” While resigning himself to the inclusion of a “notwithstanding” clause that would reduce the scope of the new constitution with respect to freedom of expression, religion, and language, Trudeau achieved his three main objectives. The right of francophones outside Quebec to have their own schools, “where the number of those children so warrants,” was stipulated in Article 23 of the new constitution. Anglophones coming to Quebec from other provinces would have access to English schools there, in violation of the Quebec clause of Bill 101, which granted this right only to anglophones from Quebec. But, unlike Ontario – whose French-speaking minority, while smaller in number than the English-speaking minority in Quebec, was nevertheless substantial – only Quebec had official bilingualism imposed on its parliament and courts, in keeping with Article 133 of the BNA Act, which was confirmed in the new constitution. To Lévesque, this was an injustice that would lead him to say that Trudeau had bartered institutional recognition of official bilingualism in Ontario for Premier William Grenville Davis’s support for his plan of repatriation. Lastly, there was no recognition of Quebec as a distinct society in the constitution and no right of veto, but there was a right of opting out with no financial compensation.

For Lévesque, it was a total disaster. The text of the new constitution reduced the powers of the only French government in the federation without its consent and fell so far short of the historic demands of Quebec, which was now subject to the law of the strongest, that he refused to sign it. This meant that the second most populous province in Canada did not recognize the fundamental law of the country, despite being bound by it. On 2 Dec. 1981, the day on which the House of Commons passed the motion on the new constitution, Lévesque had the fleur-de-lys flown at half-mast at the parliament buildings. There were now indeed two Canadas, as Trudeau and Lévesque had just demonstrated.

Worn down by his setbacks with the referendum, Lévesque found it difficult to come to terms with this new defeat. He became disillusioned and lost his grip in the final three years of his political career, during which he suffered blow after blow. Scarcely had he returned from the Ottawa summit when he learned that Claude Morin, the minister of intergovernmental affairs and the person mainly responsible for negotiations on the constitution, had taken money from the RCMP in exchange for information about the PQ. Lévesque would carry this secret with him to the grave. In the early 1980s a severe economic recession drove unemployment to new heights, a nasty shock for his government, which was struggling with a deficit of $700 million. He insisted that the unionized workers in the public sector, whose jobs were guaranteed and whose wages were higher than those in the private sector, do their share and give up some of their benefits. In June 1982, faced with the unionists’ refusal, Lévesque secured royal assent to the Act respecting remuneration in the public sector, which imposed wage cuts. That meant war. In December he promulgated the Act respecting the conditions of employment in the public sector, which imposed retroactive wage cuts of 19.45 per cent. The province was paralyzed by an avalanche of illegal strikes, which was brought to an end in February 1983 by special legislation, the Act to ensure the resumption of services in the schools and colleges of the public sector. He let himself be guided by the general interest, but he thereby attacked his electoral base and divided his party.

In the summer of 1984 the leader of the federal Conservatives, Martin Brian Mulroney, talked about national reconciliation and promised to bring Quebec to the constitutional table if his party were elected. Lévesque saw this overture as the longed-for opportunity to get rid of the hated federal Liberals and especially as a chance to recover from his constitutional setback of November 1981. Now that the referendum had been lost, he saw no point in discussing sovereignty, at least for a while. It was still on the horizon, but would not be an issue in the next election, expected to be held in a year. He was ready to take the “beau risque” (to borrow an expression from the title of a novel by François Hertel) of federalism, about which he made the following comment in November 1984, in Défis québécois, a PQ periodical published in Montreal: “It must be noted, after all, that we are not in a gulag!” And so Lévesque accepted the outstretched hand of Mulroney, who had become prime minister on 4 September, and he declared a moratorium on the issue of sovereignty, which tore his government apart. In November 1984 two of the original warhorses, the most influential ministers in the cabinet, Parizeau and Laurin, resigned. Convinced that their leader had lost faith in the cause, five other ministers – Gilbert Paquette, Denise Leblanc-Bantey, Jacques Léonard, Louise Harel, and Denis Lazure, and two backbenchers – Pierre de Bellefeuille and Jérôme Proulx – followed suit.

These defections undermined Lévesque’s authority and led him to behave erratically. He fell into a depression. In January 1985, in severe psychological distress, he had to be hospitalized against his will, in the interests of state security. The man was ill. At 62 years of age and worn out, he appeared to the youngest of his ministers and mnas, who spent the entire spring openly challenging his leadership, to be finished. Lévesque would cling to power until June. On 20 March he took advantage of the spring session to put a motion recognizing the rights of aboriginals through the National Assembly. This issue had been dear to him since the 1960s, and once he became premier he had made it his personal responsibility. Six years earlier, in December 1978, he had created a historic precedent by convening a meeting in Quebec City between the provincial government and the chiefs and representatives of 40 Quebec bands, with a view to initiating a rapprochement between whites and native people.