Source: Link

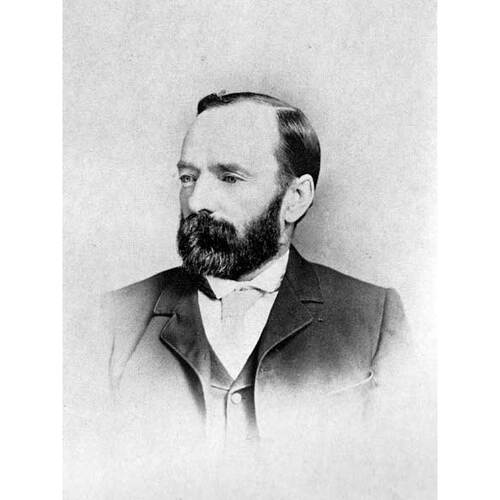

ASHDOWN, JAMES HENRY, tinsmith, businessman, and politician; b. 31 March 1844 in London, England, eldest of at least six children of William Ashdown and Jane Watling; m. first 30 Nov. 1872 Elizabeth Allen (d. 1873) in Poplar Point, Man.; m. secondly 10 Feb. 1876 Susan Crowson in Winnipeg, and they had one son and three daughters; d. 5 April 1924 in Winnipeg.

William Ashdown brought his family to Upper Canada in 1852. They settled first in Etobicoke Township, but later moved to Weston (Toronto), where William taught school for a time and subsequently ran a store. Although James worked as clerk in the store from age 11, he continued to study at night school. When the store failed in 1862, the family moved to a bush farm in Brant County. At age 18 James left home and was apprenticed to John Zryd, a tinsmith in Hespeler (Cambridge), for three years. He kept the books of a local blacksmith to supplement his wages.

At the end of his apprenticeship, Ashdown headed west and worked for ten months on the construction of a blockhouse at Fort Zarah in Kansas. His experiences in the west left him restless and eager for new opportunities. In 1868 he set out for Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) in the Red River settlement (Man.). He arrived at the end of June and took on various jobs. In 1869 he signed on with the survey crew of John Stoughton Dennis*. His savings from these jobs and a loan of $1,000 from Dennis allowed him to set up a tinsmith business and on 14 September to purchase the hardware store of George Moser.

Ashdown had arrived in the Red River settlement at a time of increasing uncertainty over the implications of the transfer of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territories to Canada. He felt that the actions of businessman John Christian Schultz* exacerbated tensions. Nonetheless, his sympathies were with Schultz’s Canadian party, which favoured annexation to Canada. Reluctantly, he joined the small, armed group that attempted to keep Schultz’s warehouse from falling into the hands of Louis Riel*’s provisional government. On 7 Dec. 1869 Riel and his supporters forced their surrender. Ashdown and the others were confined in Upper Fort Garry for 69 days.

With the establishment of Canadian governance, Ashdown concentrated on his business, meeting the growing demands of newcomers for stoves, stove-pipes, metal roofing, and all varieties of tinware and hardware. Because of the cost of transporting his goods into the region, he was one of several Winnipeg businessmen who operated the Merchants’ Line of steamboats on the Red River from 1871 to 1873 in competition with those owned by James Jerome Hill*.

The demand for hardware and metal ware was considerable in the frontier market. In 1875, 1878, and 1880 Ashdown expanded his Winnipeg premises. In 1881 he opened branches in Portage la Prairie and Emerson and in 1889 in Calgary. The credit reports of R. G. Dun and Company charted his rapidly increasing business assets from less than $2,000 in 1870 to $25,000–$50,000 in 1876 and $75,000–$150,000 in 1881. Already the west’s major hardware merchant with capital estimated at $200,000–$300,000 in 1891, he benefited even more during the boom of the late 1890s and first decade of the 1900s through his wholesale operation.

In 1896 Ashdown constructed a large warehouse in Winnipeg, which he expanded in 1902 and again in 1906. To advertise his business, on 6 March 1900 he dispatched from Winnipeg the Ashdown Special, a 40-car freight train pulled by three locomotives. Prominently displaying his name, the train travelled only during daylight to various prairie centres to fill orders for the current season. The train’s length attested not only to Ashdown’s sales, but also to the advantages that differential freight rates gave Winnipeg as a wholesale centre. The complaints of British Columbia and prairie boards of trade from 1907 persuaded the Board of Railway Commissioners, in a number of decisions up to 1914, to reduce Winnipeg’s favoured position. Ashdown was already well positioned to respond to changing transportation costs. He had expanded his Calgary branch into wholesaling in 1909. In 1911 he transferred a branch operation set up in 1896 in Nelson, B.C., to Saskatoon (Sask.), where he had a large warehouse erected. By 1911 his assets exceeded $1,000,000 and by World War I he employed over 300 workers. In 1923 he opened a branch in Edmonton.

The importance of transportation policy for his business had drawn Ashdown to politics. He was a member of the Winnipeg City Council in 1874 and 1879 and was active on the Winnipeg Board of Trade from its founding in 1879. As its president in 1887, he prepared pamphlets that criticized the monopoly of the Canadian Pacific Railway and denounced the government of Sir John A. Macdonald* for “the abuse of the vice-regal veto power” during the controversy over the federal disallowance of provincial railway legislation [see John Norquay*]. He continued his opposition to the CPR, carrying the board of trade’s complaints about rates to the railway committee in 1894 and pressuring the newly elected government of Wilfrid Laurier* in March 1897 to reduce rates. In 1903 he was appointed to represent the west on the royal commission on transportation.

Ashdown’s prominence and advocacy of Winnipeg had led him to enter federal politics. In 1896 he ran unsuccessfully as a Liberal in Marquette. On the Manitoba school question he declared his position by sharing a platform with Joseph Martin and urging Manitobans to welcome D’Alton McCarthy*. In 1911 he again stood unsuccessfully for the Liberals, this time in Winnipeg and he campaigned in favour of reciprocity. It was in the municipal arena, however, that he made his political mark.

In November 1906 Ashdown had agreed to enter the mayoralty election. The contest marked a departure for city government since it was the first to elect a board of control and to implement administration by commissioners. Ashdown had advocated municipal reform for two decades. In 1883 he had joined a citizen’s committee to investigate the city’s debt and irregularities in its tax assessment and collection system. In November 1895 he chaired a new citizen’s committee on reform of municipal government. Both of these initiatives expressed the concerns of businessmen and property owners that municipal government, in which council initiated legislation and committee chairs expended funds, was too decentralized to be responsible to those with a stake in the city. The corporate model instituted through a board of control promised sound business management.

The major issue in the election of December 1906 was Ashdown himself. His main opponent, former alderman J. G. Latimer, sought election, “to represent the city as a whole – to see that the laboring man has a fair chance against the monied interests.” The Independent Labor Party endorsed no candidate, although its chairman, Arthur W. Puttee*, favoured Latimer. His newspaper, the Voice, predicted that the trade unionists “most assuredly will not vote for Ashdown.” Ashdown countered aggressively, proclaiming that he was not opposed to unions and that he favoured “paying a good fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work.” Moreover, he had long been a critic of large corporations. He had fought the HBC’s attempts to prevent municipal incorporation in 1872–73 and as a city councillor he had confronted the company’s influence. As well, he charged that William Mackenzie, Donald Mann*, and their Winnipeg Electric Railway Company controlled Latimer and he contended that the street railway franchise should never have been given to a private company. “What might be called the natural monopolies, water and light,” should be owned and operated “by the people in the interest of the people.” Ashdown won by the largest margin to that time in a Winnipeg civic election.

Although Ashdown had been a member of the Power Association, a group of prominent businessmen who had pressured the provincial government of Rodmond Palen Roblin* in 1905 to pass legislation permitting the city to sell electric power generated at its own plant, he shocked supporters not long after taking office by arguing that the construction of a municipal power utility be postponed. The state of the city’s finances had surprised him. The city had overdrawn its account with the Canadian Bank of Commerce by $2,900,000 and owed another $1,300,000 to the Bank of Scotland. In January 1907 the Commerce, willing to hold only $750,000 of Winnipeg’s debt, pressed Ashdown to refinance the city’s obligations. He was turned down by eight major Canadian banks. He persuaded the Commerce to accept another $250,000 in debt and secured $1,150,000 from several British and American lenders, but at rates reaching seven per cent.

In this context, raising money for hydroelectric development was a daunting prospect. The advice Ashdown received in Canada and abroad was not encouraging and he recommended to council that the city postpone all non-essential expenditure until its finances were reorganized. In his view, improvements to the city’s water supply should in any case receive a higher priority than hydroelectric development. His recommendation to delay the power project provoked controversy. When the matter came before the council and board of control on 5 Nov. 1907, few accepted Ashdown’s reservations and some suspected his motives. Controller William C. W. Garson, who led the faction supporting immediate construction, asserted that “power is a necessity, and water . . . is not.” The labour press had long supported hydroelectric development, hoping that the transformation of Winnipeg into a manufacturing centre would create jobs. Councillor A. H. Pulford later charged that “the financiers and the corporations were trying to beat out the power scheme. It was a fight between capital and the people.” The council and board of control voted 13 to 5 to accept a financial arrangement from the Anglo-Canadian Engineering Company, the only firm that had tendered for the entire power project, but Ashdown vetoed their decision.

With the expiry of Anglo-Canadian’s bid and in the absence of another contractor, the campaign for immediate construction lost its steam. Criticism of Ashdown persisted, but he had argued only to postpone, not cancel the scheme. His position was so widely accepted that in the election campaign which began not long after his veto the hydroelectric project was not an issue. He was acclaimed mayor late in 1907 for a second and uncontroversial term.

The controversy revealed that, regardless of his position, Ashdown was often perceived to represent capitalist interests and was criticized for it. His role in the dismissal of the Reverend Salem Goldworth Bland* as professor of church history at Wesley College provided another example of the opprobrium easily attached to business success. Ashdown had been a member of the college’s board of directors from its founding in 1888, bursar from 1888 to 1890, and vice-chairman from 1890 to 1908; he would serve as chair from 1908 to 1924. In 1917 the college faced a difficult financial situation and needed to reduce expenses. In early June it informed Bland and two others that their services were no longer required. Because of Bland’s social activism, the firings provoked controversy within the Methodist Church and among the public.

Bland charged that wealthy businessmen who had declined to contribute to the college’s endowment fund while he was on faculty had pressured the college’s board to fire him. Letters and articles in the local press echoed his interpretation. In response, the Saskatchewan Conference of the Methodist Church empowered a commission to investigate in September 1918. Ashdown chafed under the commission’s questioning. He reiterated that the board sought only to reduce expenses, but admitted that he thought Bland’s activism had hurt the college’s fund-raising. The commission’s report upheld the board’s explanation of the dismissal, but also wondered why more consideration had not been shown to Bland.

In response to Bland’s questions before the commission, Ashdown had declared that he had let go his own employees only for incompetence, never for financial reasons. Ashdown was a paternalistic employer, confident that he treated his workers fairly and he was hence unlikely to be responsive to labour’s demands for greater control over conditions of employment. As with other businessmen who were not directly involved in the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 [see Mike Sokolowiski*], his exact role in that conflict is not clear. He no doubt sympathized with efforts to suppress what increasingly seemed to his class to be a revolutionary disruption of civil order. The conflict disturbed him, however. He conceded that some new basis had to be found for the relations between capital and labour.

Ashdown represented western Canadian wholesalers at the National Industrial Conference of Dominion and Provincial Governments in Canada, held in Ottawa in September 1919. The conference was a result of the royal commission on industrial relations. Whatever his position during the strike, he had felt no triumph afterwards and agreed that “a realizable modus vivendi [should] be evolved whereby interests apparently antagonistic, but in reality inter-dependent, shall continue to work in harmony.” In a 50th anniversary history of his business, published just prior to the conference, he felt compelled to claim that “his relations with his own employees have been exceptionally cordial.” At the conference he would look with sympathy on the demands of organized labour, “if kept within reasonable limits.” He played only a minor role in the conference, however.

As a successful businessman, Ashdown participated in the affairs of several corporations, as a promoter of the Great-West Life Assurance Company, president of the Gold Pan Mining Company and the Canadian Fire Insurance Company, vice-president and director of the Northern Crown Bank, and director of the Bank of Montreal as well as of several mortgage and insurance companies. In addition, he contributed to a number of charities and was president of the Children’s Aid Society, a director of numerous civic organizations, and a trustee of Grace Methodist Church. In his will he left to charities $300,000 from an estate valued at $1,634,000.

His business success made James Henry Ashdown a controversial public figure in Winnipeg, especially as social conflict increased through the first two decades of the 20th century. As class positions hardened, labour spokespersons easily associated him with the interests of capitalism. He was indeed a man of his class and his times. His views on a number of public issues, however – his criticism of monopolies, desire for a corporate model of government, support for the reformist provincial Liberal party, preference for safe water over public power, and willingness to reach some accommodation with the conservative elements of organized labour – revealed that he was much more of a progressive than many recognized. His public demeanour did little to promote understanding or sympathy. Accustomed as a businessman to making unchallenged decisions, he was impatient to the point of blustering anger when others did not readily accept his positions or explanations. Even the Reverend John Henry Riddell, principal of Wesley College and a friend, conceded, “We never met without a difference of opinion.” Ashdown died unexpectedly and had remained actively involved in his business to the end.

As president of the Winnipeg Board of Trade, James Henry Ashdown prepared the board’s pamphlet An open letter to the shareholders of the Canadian Pacific Railway Co. . . . ([Winnipeg?], 1887). In addition, he is the author of “Winnipeg’s board of control,” Canadian Municipal Journal (Montreal), 4 (1908): 445–46.

City of Winnipeg, Arch. and records control branch, City Council, communications, 1896, no.3312; 1907, nos.8154, 8162; 1908, nos.8284, 8307, 8455; Report of Marwick, Mitchell and Company on city of Winnipeg finances, 1908. Univ. of Winnipeg Library, “Proceedings of commission of Saskatchewan; [Methodist] Conference re Wesley College affairs, 1917–18” (typescript, 1918). Manitoba Free Press, 6 March 1900; 16 Oct. 1905; 29 June, 2 Nov., 6, 7, 12 Dec. 1906; 5, 9 Nov. 1907; 16 May, 1 July 1908; 1 Nov. 1915; 21 Sept. 1917; 17, 20 Sept. 1919. Edith Paterson, “It happened here: James H. Ashdown – tinsmith,” Winnipeg Free Press, 28 June 1969, Leisure Magazine. Voice (Winnipeg), 7, 14, 28 Dec. 1906; 17 May, 1, 8, 15, 29 Nov., 7, 14 Dec. 1907; 8 June 1917. Winnipeg Tribune, 29 Jan. 1910; 2 May 1911; 13 June, 6 Aug. 1917; 25 June 1924; 6 April 1965. Richard Allen, “Salem Bland and the spirituality of the Social Gospel: Winnipeg and the west, 1903–13,” in Prairie spirit: perspectives on the heritage of the United Church of Canada in the west, ed. D. L. Butcher et al. (Winnipeg, 1985), 216–32; The social passion: religion and social reform in Canada, 1914–28 (Toronto, 1971). A. F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: a social history of urban growth, 1874–1914 (Montreal and London, 1975). J. H. Ashdown Hardware Company Limited, Semi-centenary of the J. H. Ashdown Hardware Co., Limited, Calgary, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, established 1869 ([Winnipeg, 1919]). A. G. Bedford, The University of Winnipeg: a history of the founding colleges (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1976). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). D. J. Hall, Clifford Sifton (2v., Vancouver and London, 1981–85). Kenneth McNaught, A prophet in politics: a biography of J. S. Woodsworth (Toronto, 1959). The mercantile agency reference book . . . (Montreal), 1870, 1876, 1881, 1891. Newspaper reference book. Pioneers and prominent people of Manitoba, ed. Walter McRaye (Winnipeg, 1925). L. A. Shropshire, “A founding father of Winnipeg: James Henry Ashdown, 1844–1924,” Manitoba Hist. (Winnipeg), no.19 (spring 1990): 23–26. Winnipeg, Manitoba, and her industries (Chicago and Winnipeg, 1882).

Cite This Article

David G. Burley, “ASHDOWN, JAMES HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ashdown_james_henry_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ashdown_james_henry_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | David G. Burley |

| Title of Article: | ASHDOWN, JAMES HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |