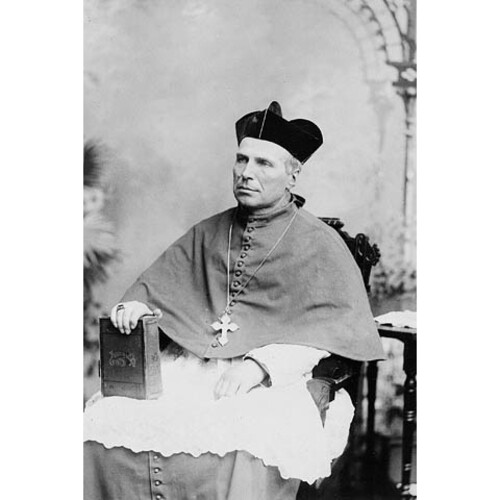

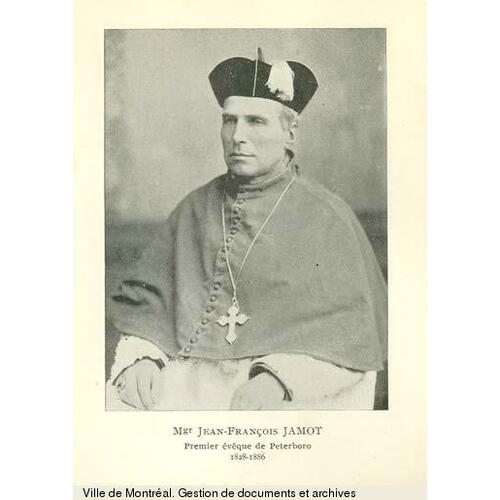

JAMOT, JEAN-FRANÇOIS, Roman Catholic missionary and bishop; b. 23 June 1828 at Châtelard, dept of Creuse, France, son of Gilbert Jamot, a farmer and landowner, and Jeanne Cornabat; d. 4 May 1886 at Peterborough, Ont.

Jean-François Jamot received his elementary education in his native town and in July 1849 graduated bachelier ès lettres from the Académie de Bourges of the Université de France. He then began studies in theology at the Grand Séminaire de Limoges and on 9 Oct. 1853 was ordained priest. The following year, while teaching classics at the Collège d’Ajain, Jamot met the French-born bishop of Toronto, Armand-François-Marie de Charbonnel*, and expressed to him a desire to work as a missionary in Canada. Charbonnel advised him to learn English, and Jamot spent eight months at All Hallows College in Dublin, Ireland, before arriving in Toronto on 10 May 1855.

A month after his arrival Jamot was appointed parish priest in Barrie, with additional responsibility for Catholics in nine surrounding townships. During his eight years in this charge Jamot displayed an aggressive and conscientious approach to the work of the church despite the frustrations of insufficient staff and finances. He built two schools and in 1857 recruited the Congregation of the Sisters of St Joseph of Toronto as teachers, bought and exchanged income properties and sites for prospective churches and schools, built churches in the outlying missions and a presbytery in Barrie, visited the missions and closely directed the spiritual life and work of the few assistant priests he had, and cultivated the support of laymen capable of helping his work. He kept his superiors in Toronto fully informed of his activities and problems, and despite his protest that he would “like rather to have nothing to do with money matters,” he left the Barrie post in September 1863 both well established and solvent, though at considerable cost to his own pocket.

In 1860, while still in Barrie, Jamot had been appointed vicar-general and chancellor of the diocese of Toronto by Bishop Charbonnel’s successor, John Joseph Lynch, who late in 1863 also named Jamot rector of St Michael’s Cathedral, Toronto. The Catholic population of the city of Toronto in 1860 had numbered over 12,000, of whom one-third were Jamot’s parishioners. The diocese, although it stretched east and west of the city, and far north, was overwhelmingly urban, Irish, and working class. Besides his work as vicar-general on what Lynch called “the organization of church machinery,” Jamot supervised the fund raising and construction for the completion of St Michael’s Cathedral and in 1866 served as chaplain to the forces on the Niagara frontier during the Fenian raids. In 1869–70 he accompanied Lynch to the Vatican Council. While in Rome Lynch argued for the creation of a separate diocese for the northern reaches of the diocese of Toronto.

The efforts of Lynch and Joseph-Bruno Guigues*, bishop of Ottawa, to have a diocese created in northern Ontario were finally successful when on 25 Jan. 1874 Pope Pius IX created the vicariate of Northern Canada and appointed Jamot its vicar apostolic; his episcopal consecration took place at Issoudun, France, on 24 Feb. 1874, and in July he returned to Toronto.

Jamot’s vicariate was bordered on the south by the Muskoka River, from Georgian Bay east to the Lake Huron-Ottawa River watershed; it then stretched north and northwest to the extent of the political boundaries of Ontario, and included the Canadian islands in lakes Superior and Huron. He estimated that there were approximately 8,000 Catholics in a total population of over 20,000; the inhabitants previously had been Indians, French Canadians, and Métis, but the federal and Ontario governments were encouraging immigration and the building of railways in the area, and an influx of construction workers and settlers of varied ancestry had already begun. Jamot had the help of ten priests, including six Jesuits, who manned 13 chapels in the Algoma District, but in the districts of Parry Sound and Muskoka there were no churches and no priests; the total value of church property he estimated at less than $3,000. Five schools were run by religious orders of men and women – two at Wikwemikong on Manitoulin Island, one at Garden River, and two at Fort William (now part of Thunder Bay) – with 200 Indian students.

Jamot installed himself at Sault Ste Marie in September 1874 and, having started the construction of a church there, began to cast around for sources of support. He fixed upon the Society for the Propagation of the Faith in Paris, and did not hesitate to play upon the sympathies or prejudices of its directors. For the vicariate’s first full year of operation Jamot estimated the costs of personnel and of building maintenance and construction at $4,500, with income of only $240. He also alerted the society to the activities of missionaries of the Church of England who were attempting to undermine the faith of Catholic Indians and to the recent election of a “Huguenot” Anglican bishop, Frederick Dawson Fauquier. Jamot argued that the conversion of the nomadic Indians could best be achieved by encouraging them to settle in Catholic tribal communities; but to do this, more priests were needed, and books and catechisms in native languages were essential. The Paris organization responded to Jamot’s appeals with generous grants, and from 1874 to 1883 annually supplied between $4,000 and $5,000, almost half of his financial requirements. He also made fund-raising tours of southern Ontario dioceses in winter, when travel throughout his vast territory was impossible.

In 1876 Jamot moved his headquarters to Bracebridge, the chief town of the districts of Parry Sound and Muskoka which were being rapidly populated by free grant settlers. He was instrumental in encouraging this settlement by publishing letters in newspapers and working closely with Ontario government officials; in December 1877 Jamot reminded Timothy Blair Pardee, the commissioner of crown lands, that through public meetings and his visits to parishes to southern Ontario he had had “a great deal to do” with attracting the “immense number of people who have come in.” In return for aiding settlement policy and for discreet help during elections, the Liberal government of Oliver Mowat* often appointed surveyors and land agents whom Jamot recommended and who he thought would encourage settlement by Catholics. But friction also characterized the relationship: Jamot attacked the government for not opening up lands on the south shore of Lake Nipissing to settlers he had recruited in Waterloo County, and Pardee was shocked in 1877 by Jamot’s “open and direct threats of determined opposition to the government unless certain requests made were not immediately acceded to.”

During the late 1870s and the early 1880s the feverish activity of settlement in the southern districts of his vicariate and of railway construction and logging in Algoma, though gratifying to Jamot, greatly increased the demands on his already insufficient funds and harried priests. As early as 1877 he had urged the apostolic delegate in Canada, Bishop George Conroy*, to recommend attaching to his vicariate part of the heavily populated and generously endowed diocese of Kingston, and in 1879 the bishops of Ontario unanimously endorsed the suggestion. On 11 July 1882 Pope Leo XIII appointed Jamot bishop of the new diocese of Peterborough, adding the counties of Durham, Northumberland, Victoria, Peterborough, and part of Haliburton to the existing vicariate. Jamot’s diocese now stretched from Port Hope to the Manitoba border; to the 27 churches, 22 schools, 14 priests, and 10,000 Catholics of the former vicariate the five counties added 20,000 members, 11 priests, 13 schools, 20 churches, and debt-free church property valued at over $200,000. From his cathedral of St Peter-in-Chains in Peterborough, which he enlarged in 1884, Jamot attacked his work with a new vigour.

Jamot strengthened the well-established church in the southern counties by creating new missions, building churches, establishing separate schools and recruiting religious orders to teach in them, and supervising the education of seminarians, six of whom were ordained for service in his diocese between 1883 and 1886. But the problems of the northern part of the diocese required more unconventional methods. The education of native children continued to concern Jamot: he repeatedly argued with the federal government for larger grants, better salaries for teachers, and Indian involvement in school administration. He also denounced as bureaucratic folly the selection of teachers and textbooks by Indian agents and the attempts to make compulsory both attendance and English as the language of instruction. When a Jesuit at Port Arthur (now part of Thunder Bay) complained to Jamot in 1883 that the Indians, “the little ones who were crushed by the mighty ones,” were cheated of the timber rights on reserve lands, Jamot tackled the federal government, dismissing Sir John A. Macdonald*’s charge that the Indians were engaged in a “conspiracy” to revoke a legal surrender. Political action in the pursuit of Christian goals was risky since, as another missionary at Fort William suggested, Macdonald was “dissatisfied at seeing the friendly relations which exist between the Episcopacy and the clergy of Ontario and the Ontario Government.”

Jamot showed special concern for the welfare of the thousands of men who worked in lumber camps, mines, railway construction, and public works projects in the north. He encouraged the Sisters of St Joseph to establish a hospital at Fort William, opened in 1884, to treat injured workers, and in 1883 he stationed a priest on the railway line between the construction camps of North Bay and Sudbury. During his last extensive tour of the diocese late in 1884 Jamot saw new settlements, churches, schools, and orphanages throughout the north. When on 10 Nov. 1885 he left Peterborough for Rome to report to Leo XIII on the condition of his diocese, Jamot represented a church still hard-pressed for resources yet one which had successfully met numerous and unique challenges.

Jamot resumed his work after his return from Rome in March 1886, but contracted pneumonia and died in Peterborough on 4 May. Relentless in his commitment to his goals and adept at marshalling and manipulating any means of furthering his work, Jamot was a builder of heroic proportions whose devotional workbooks also reveal the vibrant spiritual life that those around him always felt.

Arch. of the Archdiocese of Toronto, Barrie, Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, general corr. 1849–99; Edward Kelly, “Biographical notes of some interest to me probably not so to anybody else” (copy at Univ. of St Michael’s College Arch., Toronto); Peterborough; St Michael’s Cathedral, 1866–73. Arch. of the Diocese of Peterborough (Peterborough, Ont.), Bishop J. F. Jamot corr., 1862–81; 1882–86; Diocese of Peterborough, Canada, Memorandum book; Personal effects of Bishop Jamot. Daily Evening Review (Peterborough), 6, 7 May 1886. Daily Examiner (Peterborough), 4–6 May 1886. E. J. Boland, From the pioneers to the seventies: a history of the diocese of Peterborough, 1882–1975 (Peterborough, 1976). H. C. McKeown, The life and labors of Most Rev. John Joseph Lynch, D.D., Cong. Miss., first archbishop of Toronto (Montreal and Toronto, 1886). J. S. Moir, “The problem of a double minority: some reflections on the development of the English-speaking Catholic church in Canada in the nineteenth century,” SH, no. 7 (April 1971): 53–67.

Cite This Article

Alan Stillar, “JAMOT, JEAN-FRANÇOIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jamot_jean_francois_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jamot_jean_francois_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alan Stillar |

| Title of Article: | JAMOT, JEAN-FRANÇOIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 26, 2025 |