Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BRYCE, PETER HENDERSON, physician and civil servant; b. 17 Aug. 1853 in Mount Pleasant, Brant County, Upper Canada, son of George Bryce and Catherine Henderson; brother of George Bryce; m. 17 Aug. 1882 Kate Lynde Pardon (d. 14 March 1931) in Whitby, Ont., and they had four sons and two daughters; d. 15 Jan. 1932 at sea and was buried in Beechwood Cemetery, Ottawa.

The second son of a prominent Scots Presbyterian family, Peter H. Bryce attended Upper Canada College and then earned his ba (1876), ma (1877), and mb (1880) at the University of Toronto, winning the silver medal in medicine and the Starr gold medal. In Edinburgh he was admitted to the Royal College of Physicians, and in Paris he briefly studied neurology at Jean-Martin Charcot’s clinic in the giant Salpêtrière public hospital. Bryce returned to Canada and opened a general practice in Guelph, Ont., and in 1882 Arthur Sturgis Hardy*, provincial secretary in Oliver Mowat*’s Liberal government, appointed him secretary of the Provincial Board of Health. He would hold this position for 22 years, working with such individuals as John Joseph Cassidy* and John Joseph Mackenzie* to grapple with enormous problems that received little government funding. In 1888 he completed his md at the University of Toronto, but by 1890 he had closed his medical practice because of the pressure of his work as a civil servant, which increased in 1892 when he also became deputy registrar general in charge of vital statistics. Along with other physicians in the field of public health such as Edward Playter*, Charles John Colwell Orr Hastings, and John Gerald FitzGerald, Bryce was an advocate of preventive medicine and improved sanitation, particularly in urban areas. His reputation soon spread: he was elected president of the American Public Health Association in 1900, and four years later he was made vice-president of the American International Congress on Tuberculosis. As well, he was an active member of the Canadian Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis.

In 1904 Clifford Sifton*, minister of the interior and superintendent general of Indian affairs in the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, appointed Bryce chief medical officer of his two departments. In this position Bryce was responsible for the medical inspection of newcomers at a time of massive immigration, as well as for overseeing the health conditions of the indigenous population. A member of the Canadian Purity-Education Association and a regular commentator on contemporary questions of social and moral reform, Bryce agreed with Sifton that immigrants from the rural areas of southern and eastern Europe were preferable to those who belonged to the working classes of Great Britain and the United States, who, as Bryce put it, “have been for several generations factory operatives and dwellers in the congested centres of large industrial populations.” In keeping with contemporary medical ideas, he believed that city life led to “a type of feeblemindedness” and the “degeneration of a race who once had Anglo-Saxon freemen for their ancestors.” Bryce kept statistics on immigrants who were suffering from tuberculosis and knew that British physicians often recommended a change of climate as treatment for the disease. He therefore advised them to send their well-off patients in the “initial stage of the disease” to Canada’s farms and pleasant valley orchards, “and there, with English capital, English ideals and English methods,” they would regain their health.

Bryce had been well aware that tuberculosis was prevalent among Ontario’s indigenous population before he joined the federal civil service, and had struggled to counter the disease by setting up tent sanitariums staffed by trained nurses in the southwestern part of the province. Despite his presentation of facts and figures showing the need for a new approach and the support of a multi-denominational committee chaired by lawyer and philanthropist Samuel Hume Blake*, money was not forthcoming. In 1907 Bryce, in his capacity as chief medical officer of the Department of Indian Affairs, reported on the health conditions of 35 industrial and boarding schools on the prairies. Run by churches, funded by the state, and supervised by men such as Hayter Reed, former Indian commissioner for the North-West Territories, these institutions were intended to assimilate indigenous people. Bryce did not examine the children, but instead inspected the state of the school buildings as well as the available student records. His Report on the Indian schools of Manitoba and the North-West Territories made clear the links between poor sanitation and ventilation in the schools and the infection of undernourished children. “We have created a situation so dangerous to health,” Bryce wrote, “that I was often surprised that the results were not even worse than they have been shown statistically to be.” Of the 1,537 students with records, nearly 25 per cent were dead, and at the school in the File Hills Colony run by William Morris Graham in southern Saskatchewan, 69 per cent of all ex-pupils had died. Bryce noted an “intimate relationship between the health of the pupils while in school and that of their early death subsequent to discharge.” His report, distributed to principals and employees of the department, found its way into the hands of journalists, who were naturally outraged by what they read. For those Indian Affairs bureaucrats who had for some time been planning to shut the expensive industrial schools, the negative publicity was not altogether unwelcome, but many principals took offence: Father George Hallam, for example, dismissed Bryce’s ideas as “new fangled” and declared that he “shouldn’t expect palaces for children.” In the Report’s recommendations, which were never made public, Bryce directly blamed the government for the appalling conditions [see Allen Patrick Willie] and especially criticized its inadequate per-capita funding, which forced the churches to enrol more students and feed them less. His suggestion that the government assume complete financial and administrative control of the schools went far beyond what his superiors were willing to do.

Two years later an inspection of 243 children in southern Alberta schools found high rates of tuberculosis, prompting Bryce to recommend not only the standard treatment of fresh air, rest, and an improved diet, but also the medical supervision of students without interference from the churches. His advocacy of non-denominational schools and increased government financial commitment was not well received. Duncan Campbell Scott*, the superintendent of education for the Department of Indian Affairs, found Bryce’s recommendations “scientific … [but] quite inapplicable to the system under which these schools are conducted.” Citing the work of internationally known physician William Osler*, Scott made a few limited reforms: improved medical inspections upon enrolment, an increased per-capita grant, and contracts with each school binding it to higher standards of sanitation and diet. Scott assured his superiors that these commonsensical adjustments would “remove the imputation that the Department is careless of the interests of these children.” Bryce’s recommendations would surely have bettered, if not saved, many lives, but the residential schools (as they were renamed after 1923) would remain essentially unchanged until 1946.

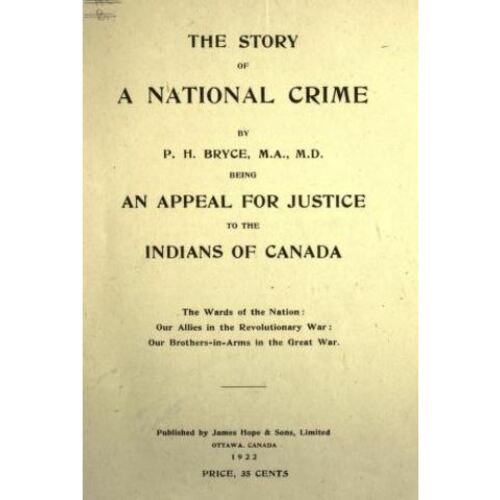

Bryce was pensioned off in 1921, and the following year he wrote a scathing attack on the Department of Indian Affairs, blaming Scott personally for the continuing deaths of children after 1907. In The story of a national crime he claimed that when Scott became deputy minister in 1913 he effectively pushed Bryce out of Indian Affairs. Accusing the “reactionary” Scott of failing to implement even the simplest measures to deal with ongoing health problems, Bryce wrote: “This trail of disease and death has gone on almost unchecked by any serious efforts on the part of the department of Indian Affairs.” He also denounced the Union government of Sir Robert Laird Borden for refusing to include responsibility for the health of indigenous people in the mandate of the new Department of Health, established in 1919 under Newton Wesley Rowell*. Bryce was openly bitter that he had not been appointed its first deputy minister, however, and his resentment may have diminished the public impact of his criticisms of the government.

Although Bryce pursued his quarrel with Scott and the department that he led after he left the civil service, he also followed other interests during his retirement. He was a founder of the Canadian Historical Association and a member of the Arts and Letters Club of Ottawa, and he wrote on topics as diverse as the life of Sir Oliver Mowat and the history of the Quinte loyalists. He died at sea on 15 Jan. 1932 while travelling to the West Indies for his health, just two weeks after the death of Dr Henderson Lynde Bryce, his youngest son. Bryce’s contributions to Ontario’s public health and to Canadian immigration practices were recognized in his time, but his attempts to extend even the most basic public-health protections to indigenous individuals were not. Not until the late 20th century, when Canadians began to listen to indigenous voices and historians began to tell the shameful story of ill health in the residential schools, would his efforts finally be acknowledged. In 2011 the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada established awards in his honour to recognize adults and youths who have advocated for systemic changes that will benefit the health and well-being of indigenous children in Canada.

Peter Henderson Bryce is the author of: Report on the Indian schools of Manitoba and the North-West Territories (Ottawa, 1907; a copy with background material is available at LAC, RG 10, vol.4037, file 317021); “Tuberculosis in Canada as affected by immigration,” British Journal of Tuberculosis (London), 2 (1908): 264–67; “Effects upon public health and natural prosperity from rural depopulation and abnormal increase of cities,” American Journal of Public Health (New York), 5 (1915): 48–56; “Feeblemindedness and social environment,” American Journal of Public Health, 8 (1918): 656–60; “The scope of a federal department of health,” American Journal of Public Health, 9 (1919): 650–53; and The story of a national crime: being an appeal for justice to the Indians of Canada … (Ottawa, 1922).

LAC, RG 10, vol.3957, file 140754-1, “Notes on Dr. Bryce’s report – with suggestions for future action,” 7 March 1910. A. J. Green, “Humanitarian, m.d.: Dr. Peter H. Bryce’s contributions to Canadian federal native and immigration policy, 1904–1921” (ma thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1999). M. K. Lux, Medicine that walks: disease, medicine, and Canadian plains native people, 1880–1940 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 2001). J. R. Miller, Shingwauk’s vision: a history of native residential schools (Toronto and Buffalo, 1996). J. S. Milloy, “A national crime”: the Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879 to 1986 (Winnipeg, 1999). Alan Sears, “Immigration controls as social policy: the case of Canadian medical inspection 1900–1920,” Studies in Political Economy (Ottawa), 33 (1990): 91–112. Megan Sproule-Jones, “Crusading for the forgotten: Dr. Peter Bryce, public health, and prairie native residential schools,” Canadian Bull. of Medical Hist. (Waterloo, Ont.), 13 (1996): 199–224. E. B. Titley, A narrow vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver, 1986). Mariana Valverde, The age of light, soap, and water: moral reform in English Canada, 1885–1925 (Toronto, 1991). G. J. Wherrett, The miracle of the empty beds: a history of tuberculosis in Canada (Toronto, 1977).

Cite This Article

Maureen K. Lux, “BRYCE, PETER HENDERSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bryce_peter_henderson_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bryce_peter_henderson_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Maureen K. Lux |

| Title of Article: | BRYCE, PETER HENDERSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | December 17, 2025 |