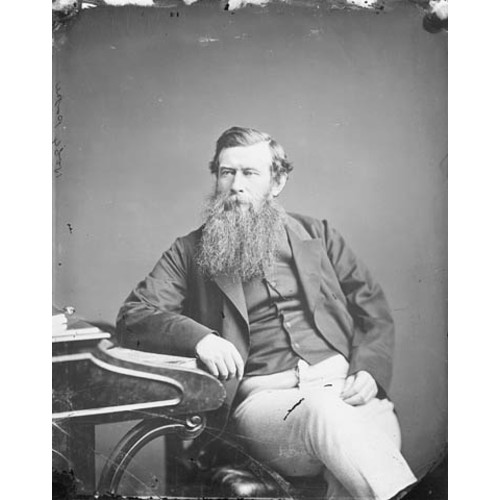

POPE, WILLIAM HENRY, lawyer, land agent, journalist, politician, and judge; b. 29 May 1825 at Bedeque, P.E.I., elder son of Joseph Pope* and Lucy Colledge; d. 7 Oct. 1879 at St Eleanors, P.E.I.

William Henry Pope received his early education in Prince Edward Island and proceeded to higher studies in England, from which his father had emigrated in 1819. William read law at the Inner Temple in London, then returned to his native colony to article in the office of Edward Palmer* in Charlottetown; he was called to the bar in 1847. He married Helen DesBrisay in 1851, and they had two sons and six daughters; their elder son, Joseph Pope*, became private secretary to and biographer of Sir John A. Macdonald*.

Like many contemporary lawyers in the colony, William Pope also became a land agent. His legal practice and his land business remained his principal activities until he entered journalism and government office in 1859. His father, a shipbuilder and politician, was a prominent member of the local élite which originally served primarily as an intermediary between the absentee landowners of the Island and their tenants; consequently, William Pope gained important clients, such as Captain Cumberland, Lady Cecilia Georgiana Fane, and Charles Worrell*. It was as Worrell’s agent that Pope acquired lasting unpopularity on Prince Edward Island. In 1854, after the Liberal government had passed a land purchase act, Worrell’s trustees, on the Island, decided to advise him to sell. They delegated one of their members, Theophilus DesBrisay*, Pope’s father-in-law, to gain Worrell’s acquiescence. DesBrisay persuaded Worrell to give up his estate to the government for £10,000, but withheld this news from the other trustees. He then, apparently with no justification, informed Worrell that the government no longer wished to buy the property. Worrell now suggested that the estate be offered to a certain potential buyer for £9,000, but DesBrisay failed to make the offer. Having thus by his own authority suppressed both possible transactions, he next advised Worrell to discuss the matter with Pope – who happened to be on his way to England.

Worrell, impatient to be rid of his debt-encumbered and far-away estate, readily accepted Pope’s offer of £14,000. On 28 Dec. 1854 Pope and his financial backers – his father, his father-in-law, and one George Elkana Morton of Halifax – resold the property to the government for £24,100. The Liberals had been persuaded to pay what they knew to be an exorbitant price by Pope’s thinly veiled threats to take the tenantry on his new estate to court for payment of arrears in rent. The property consisted of five adjacent townships, numbers 38 to 42, in northern Kings County, and such a proceeding would have caused riots. In addition, DesBrisay allegedly extorted £1,700 from Worrell for his “services.” However, the failure of Pope and his associates to transfer all of the promised 81,303 acres to the government led to the refusal of the latter to pay the final £3,000 of the purchase-price. Although his actions became public knowledge, Pope never took the trouble to deny vigorously the essentials of the case against him; as he was capable and politically ambitious, it is probable that he would have contested them could he have done so successfully. The result of this jobbery, unique in its magnitude for this period on the Island, was that his public reputation was permanently scarred.

As the 1850s progressed, William and his younger brother James Colledge Pope* became increasingly active in the Conservative party, which was then in opposition. When the Liberal government under George Coles was defeated in 1859, James, an assemblyman, was named to the Executive Council, and William, who was a member of neither branch of the legislature, was appointed colonial secretary. William’s appointment was in accord with the policy of “non-departmentalism” practised by the new government. The Tories claimed that the Liberals had instituted a “spoils system,” with the legislators themselves as the prime recipients of patronage, and they had promised to exclude representatives of the people from public offices of emolument, which were supposedly to be filled by nonpartisans. Pope was immediately recognized by the Liberals as the most influential of the new government’s public officials. Two months earlier Edward Whelan* had written that “Mr. Pope is a man whom the Tories rather fear than respect . . . he has more cunning, more perseverance in pursuit of his object (no matter what it is,) and more real talent than any other man in his party.”

William Pope had already assumed a strategic position within the ruling élite. Shortly after the election of 1859, Duncan MacLean*, the editor of the Islander, the leading Conservative newspaper in the colony, had died, and Pope had been appointed his successor by John Ings, the Islander’s publisher and the new queen’s printer. As an editor, Pope maintained the important position of his paper, and, in the tradition of MacLean, carried on a running battle with Whelan, the publisher and editor of the Examiner. Pope and Whelan were controversialists by nature, and they exhibited an interesting contrast in abilities Whelan was a master of literary style and the pungent epigram; Pope, whose style was more laboured, exhibited precise logic and flawless argument. Together, they provided the Island public with an invaluable political dialogue.

The most momentous and lingering issue in Island politics prior to confederation was the land question. Pope’s position was that although leasehold tenure was “obnoxious” and had “injurious” effects upon the colony, whatever was to be done must be done “without infringing the rights of property.” The absentee landlords were “not blamable for the existence of the leasehold system”; rather, the “great injustice” had been inflicted by the imperial government in 1767 when it imposed the system upon the Island. The current owners had full legal title to their holdings, and hence all benefits to their tenants must come “by the favor of the Proprietors.” Radical schemes such as escheat were out of the question: “the rights of property – sacred in all civilized countries – will be inviolably preserved.” The proper course for the tenantry was to enter into “friendly negociation [sic] with the Proprietors.” The new Tory government, intimately connected with men of position and wealth, was ideally suited to play the role of mediator between landlord and tenant.

But it was not over the Worrell estate, or the land question in general, that Pope gained his greatest fame – or notoriety – on the Island. The Conservative victory of 1859 had been accomplished largely through skilful exploitation of Protestant anxieties over the Bible question, in which Pope himself had not taken an active part, and the result had been division of the electorate almost entirely on religious lines. Although William Pope had been born into a Methodist family, he was widely known to be an “infidel” – the contemporary Island name for atheists, agnostics, Unitarians, and apostates – and he did not have strong convictions about the intrinsic rightness or wrongness of either Protestantism or Roman Catholicism. After 1860, or when the role of the Bible in the district schools had been defined to the general satisfaction of all concerned, Pope and the premier, Edward Palmer, saw no reason for the estrangement between their party and the Roman Catholic Church to continue. In early 1861 Palmer and his chief lieutenant in the cabinet, Colonel John Hamilton Gray*, made two clandestine attempts to gain the friendship of the Catholic hierarchy by offering certain concessions in the field of education; both efforts failed, largely because of ill fortune.

Meanwhile, William Pope stumbled upon a third opportunity for reconciliation. By chance, Bishop Peter MacIntyre* mentioned to him that he planned to present a petition to the government asking for endowment of the Roman Catholic St Dunstan’s College. Pope then promised to approach the government and its friends, in order to canvass support for the grant in advance, if the bishop would postpone presentation of his petition. MacIntyre agreed, and Pope proceeded to consult with the Executive Council, the caucus, and members of the Protestant clergy. With the exception of Palmer and Gray, no one gave him much encouragement; indeed, most of those with whom he spoke said they would oppose the endowment under any circumstances.

When Pope reported his bad news to MacIntyre, the latter became angry, and declared that in the next election he would mobilize the Island’s Roman Catholics as never before in order to defeat the all-Protestant government. Pope apparently believed that the bishop was in earnest, and consequently changed his mind about the direction that relations between the Conservatives and the Catholic population should take. The Tories, it seemed, would have to rely upon a purely Protestant appeal if they were to retain the support of a majority of Island electors. In the summer of 1861, Pope published a series of “Letters to the Protestants of Prince Edward Island.” His political message, expressed in the first letter, was that “as parties now stand, any government other than an exclusively protestant one must of necessity be virtually a roman catholic one.” The letters that followed became abusive of Catholic beliefs, referring to the Real Presence as “a God made of a little flour and water,” and warning Protestants that the Council of Trent had pronounced non-believers in the Eucharist “accursed.” “Pope’s Epistles against the Romans,” as Whelan labelled the series, marked the beginning of 18 months of religious disputation in the Island press. The main protagonists were Pope and the rector of St Dunstan’s, Father Angus MacDonald*. A formidable polemicist, who always acted in full consciousness of his objectives rather than an excess of zeal, Pope was rapidly becoming the most controversial public figure in the colony, and the bête noire of the Liberals.

Father MacDonald and William Pope had already clashed in public concerning the temporal powers of the papacy, and now, in the latter part of 1861, the rector took up the defence of his church. Matters became more serious in February 1862 when MacDonald, in referring to some abusive anonymous correspondence in David Laird*’s Protestant, declared that the letters in question were obviously written “by some low rabid character who holds the same position in the literary world, that a rowdy, blackleg, or pimp does in the social one.” Such a person, said the rector, was W. H. Pope. This prompted Pope to write an open letter to MacDonald, in which he quoted St Jerome to show that Roman Catholicism and ignorance were natural concomitants, cited Baronius to prove that the early popes were “harlot chosen,” and finally asked whether, like the augurs of ancient Rome, Father Angus laughed at the credulity of those who believed that “a little wheaten flour” could become God. In the same number, “A Protestant,” who in reality was William Pope, submitted a price-list of indulgences and dispensations, dated 1514. After these inflammatory epistles, Pope retired from the quarrel.

MacDonald added a new dimension to the feud in the summer of 1862 by asking both the lieutenant governor, George Dundas, and the secretary of state for the colonies, the Duke of Newcastle [Henry Pelham Clinton], to dismiss Pope from office because of his attacks upon Roman Catholic beliefs. The attempt was unsuccessful, and after the furor surrounding it had subsided – MacDonald published his letters and Pope replied – the vendetta dropped out of public sight for two months. Then in September Pope wrote an editorial claiming: “The grand aim of the Roman Catholic Clergy on this Island is to obtain a grant for their College of Saint Dunstan. This they cannot procure unless the present Government can be ousted.” The Liberal press and MacDonald replied by asserting that the government itself had intended to endow the college. Pope denied this, and gave his full version of the conversations of the spring of 1861, which had not hitherto been made public.

In the course of his disclosures, Pope drove his accusers from the field; it was a devastating display of the logical powers of his mind, and it meant that the Palmer government retained the confidence of Island Protestants. The results of the controversies generated by the revelations of September and October were momentous: an ultramontane newspaper was founded, the militant Presbyterians and Orangemen were mobilized against “Romish aggression,” and the Conservatives won the general election of January 1863 on the religious-educational issue. William Pope entered the lists, and successfully contested Belfast, the most Presbyterian constituency in the colony. Once elected to the assembly, Pope joined the Executive Council, and remained colonial secretary, as non-departmentalism was abandoned after a trial of four years.

The session following the election was tempestuous from start to finish. William Pope, at the apex of his power and influence in Island politics, was brimming with calm spite, for he was aware that MacDonald was again writing – although in vain – to London to have him removed from office. On St Patrick’s Day, Pope introduced a bill to incorporate the colony’s Grand Orange Lodge, and the ferocity of the debate which followed has probably never, before or since, been equalled in the legislative history of the Island. The nadir was reached when George William Howlan*, a Catholic Liberal, accused Pope of having said outside the house “that a Catholic woman going to confess to a priest was the same as taking a mare to a stallion.” But the “religious question” had by this time reached a peak in intensity; within a few months it appeared to have burned itself out.

In the meantime, the land question remained unsolved. The Palmer government had in 1860 arranged for the appointment of a distinguished three-man commission, whose recommendations had been disallowed by the London government, at the urging of the proprietors. In the summer of 1863, the Island government, now led by Colonel Gray, renewed its efforts to settle the issue, and delegated two leading cabinet members, Pope and Palmer, to go to England to confer with the Colonial Office and the landlords. The two delegates proceeded to London, and on 13 October presented Newcastle with a new set of proposals; he immediately passed them on to Sir Samuel Cunard*, who at that time owned one-sixth of the land in the colony, and who was acting on behalf of a group of proprietors. Since it appeared that the negotiations would be lengthy, Palmer sailed for the Island in early November, leaving Pope alone to deal with the British government and Cunard. The Colonial Office expected little difficulty in handling Pope for they had formed an unflattering opinion of him through the unseemly vendetta with MacDonald; on 14 September the permanent undersecretary had written that “the appointment of Mr. Pope does not look as if this matter [the delegation] could come to much.”

However, when Cunard and his associates refused the October proposals, Pope responded vigorously. He wrote detailed and well-documented replies to Cunard’s statement, and declared that “high as may be the respect entertained for the legal rights of the land owners, there are cases in which they should give way to the requirements of ‘public policy’” For example, there was no possibility that full arrears in rents could be collected; the whole purpose of the delegation was to get the landlords to consent to a compromise. The consequence of intransigence, Pope predicted on 13 Jan. 1864, would be “those much to be dreaded evils, which necessarily result from wide-spread agrarian agitation.” Events soon proved him correct: the tenants of the Island were already forming a new and militant organization, the Tenant League, whose members were pledged to resist payment of rents. The commission and the delegation had failed, and by August 1865 troops were required to maintain the legal rights of property in Prince Edward Island [see Hodgson].

When the question of a union of the British North American colonies arose in 1863 and 1864, William Pope was one of the very few Islanders to advocate it enthusiastically. He attended both the Charlottetown and the Quebec conferences, and was an honorary secretary of the latter. Soon after the Quebec Conference, he found himself at odds with Palmer, who opposed confederation, and who attempted to regain the premiership at the expense of Colonel Gray. In mid-December 1864, Gray resigned under pressure; but Palmer failed to become president of the Executive Council, because William Pope came to the defence of the colonel. At issue was Palmer’s consistency on the confederation question, and Pope pursued him with the cold fury and relentless logic which he had unleashed upon MacDonald in September and October 1862. Pope won the argument, but in the longer perspective Palmer could claim a considerable victory: the Conservative party would not now lead the Island into confederation. With this in mind, and aware that public opinion supported Palmer rather than himself and William Pope, Gray refused to resume the premiership or a seat on the Executive Council.

A makeshift government, led by James Pope, took office. Although his brother was now premier, William became increasingly isolated within the cabinet. During the 1865 session, when James was on the point of moving the house into committee on the Quebec terms, William presented eight pro-confederation resolutions before his younger brother could speak. James accused William of having, “to say the least of it, acted most un-courteously.” The defeat of William’s resolutions, and the acceptance of James’s counter-resolutions, were foregone conclusions, but the incident served to widen the breach between the colonial secretary and his colleagues. The finishing blow came in the 1866 session, when William was absent on a trade delegation to Brazil: James Pope presented the “No terms Resolution” on confederation, expressing the belief that union with Canada was not a foreseeable possibility. Shortly after his return, William resigned as executive councillor and colonial secretary, in protest against this position.

The rest of William Pope’s public career is anti-climactic when contrasted with the immense power and influence which he had wielded in the first half of the 1860s. He remained editor of the Islander until Ings sold the newspaper in October 1872, but he did not even contest the election of 1867 which the Tories lost badly. The party was hopelessly fragmented by the confederation question; Gray and James Pope also declined to run. From this time until his appointment to the bench in 1873, William Pope concentrated upon two objectives: the entry of the Island into confederation, and, as the means to this end, the rebuilding of the Conservative party on a strong confederate base.

The Tories were in a sad state, but the Liberal government was vulnerable because they had their own serious divisions over the land and school questions. The session of 1868 revealed a deep fissure in their ranks over whether to give public aid to Roman Catholic schools, including St Dunstan’s, under the control of Bishop McIntyre. William Pope had already shown renewed interest in the college’s financial problems; in February he had declared in favour of a grant, without mentioning any conditions to be met. He warned of the tendency of the age to infidelity, and recommended that Roman Catholics “force” the school question upon the government.

Pope – who had with his usual coolness and deliberation changed his political strategy, not his religious convictions – kept constant pressure on the government throughout early 1868, and eventually published a draft bill that embodied the amendments he desired in the education act. In November 1868 James Pope contested a by-election in Prince County, Fifth District, on the promise to give public aid to all “efficient” schools. Despite the active support of MacIntyre, the Islander, the leader of the opposition (T. H. Haviland* Jr), and the approval of Gray, James lost badly. Consequently, the Popes decided to let the school question stand for the present. Their attempt to inaugurate a new party system on the basis of a partnership between the Conservative confederates and the Roman Catholic Liberals had been premature.

Nonetheless, William Pope did not give up his advocacy of confederation. He continued to write editorials on the subject, gave public lectures, kept in contact with John A. Macdonald, and sent memorials and pamphlets to London. The election of 1870 provided the opportunity for forging the new alliance. Palmer and David Laird, the leaders of the anti-confederate faction within the Conservative party, were defeated, and James Pope, now ambivalent on the confederation issue, was returned to the assembly as leader of the party. The Liberals had won by the margin of 17 to 13, but they immediately shattered on the rock of the school question, largely owing to the inept leadership of Robert P. Haythorne*.

Soon after the Liberals split, James Pope joined with George Howlan and his followers to form a coalition government. But in the meantime, William Pope had prepared a rationale for his brother to refuse the Roman Catholic demands, which, if met, might have split Pope’s group: no Protestant Conservative had submitted the subject of denominational grants to his constituents at the late election, and nothing, William said, could be done without a mandate from the people. Yet the Popes did not follow the example of the Protestant Liberals, and close the door for all time – denominational grants were not rejected in principle. The basis of the new alliance was mutual self-denial: no action would be taken on the confederation or school questions until they had been presented to the electorate. The Tories had won over the Roman Catholic legislators and returned to power; one of William Pope’s objectives had been accomplished.

Less than three years after its formation, the Pope–Howlan coalition led the Island into confederation. In early 1871 a sudden desire for a railway swept the Island, and the coalition responded by passing appropriate legislation. The new project, which William Pope had been advocating for several years, drove the colony to the brink of bankruptcy; by early 1872 public alarm was so great that James Pope was forced to call an election, in which his government was badly defeated. However, the damage to the Island’s finances was irreparable: Haythorne and Palmer, the strongly anti-confederate leaders of the new government, conceded defeat in February 1873 and delegated Haythorne and David Laird to go to Ottawa to negotiate terms. When they returned, a new election was called, which was won by James Pope on the promise of better terms.

With the coming of confederation in July 1873, the Macdonald government appointed William Pope judge of the Prince County Court. He had an outstanding record on the bench: of several thousand decisions, only two were appealed, and in both cases he was upheld by the provincial Supreme Court. During his career as a lawyer and jurist he was twice (in 1861 and 1878) asked to undertake the revision and consolidation of the Island’s statutes.

William Henry Pope died on 7 Oct. 1879 as the result of a stroke suffered a few days earlier. He had been a truly remarkable Islander. As well as being an outstanding member of his chosen profession, he had a wide variety of interests and connections. At the time of his death he was planning to write a history of the Island; he had done primary research in the archives of the Colonial Office and elsewhere during trips to the mother country. In London itself, he was three times (in 1863, 1866, and 1870) elected as one of the 15 honorary non-British members of the Athenaeum Club; he was also a friend and correspondent of some of the most distinguished Englishmen of the period. By the standards of the day, his tastes were quite extravagant, and despite his shrewdness, he was a poor manager of his personal finances. His sudden death left his family in difficult circumstances.

William Pope’s principal vocations were politics and journalism. With undoubted abilities he was for years considered to be the most influential member of his party. When his brother was premier, it was often said that “William made the snowballs and James threw them.” William was at the centre of the bitter religious-educational controversies of the early 1860s. He was also the Island’s most forceful and persistent advocate of confederation, and he masterminded the creation in 1870 of a new Tory party, which was destined to be the vehicle for the entry of the Island into confederation. Most famous off the Island as a father of confederation, it was, nevertheless, in the role of political manipulator that Pope was best known at home. In short, from the late 1850s to the early 1870s, William Henry Pope was the éminence grise of the Conservative party of Prince Edward Island.

[There are two collections of W. H. Pope papers; the larger is in PAC, MG 27, F2, and the other in the possession of General Maurice Pope of Ottawa to whom the author is indebted for his permission to examine the material and for a helpful interview on 20 May 1968. PAC, MG 26, A (Macdonald papers), includes a number of Pope-Macdonald letters written between 1870 and 1876. Pope appears to have been Macdonald’s closest ally on P.E.I. Letters referring to Pope’s financial problems can also be found in PAPEI, Henry Jones Cundall, letter books, 1874–78. The papers of administration for Pope’s estate are in Prince Edward Island, Supreme Court, Estates Division. Prince Edward Island, Executive Council, Minutes, 1863–66, the years during which Pope was a member of the Executive Council, can be found at PAPEI. The Grand Orange Lodge of Prince Edward Island allowed the author to examine its records. Its Annual Report, 1865, refers to Pope as “Brother, the Honorable W. H. Pope,” indicating that he was, at least temporarily, an Orangeman. Scattered references to Pope can also be found in PRO, CO 226, throughout the volumes covering the years 1857 to 1873. For details of the sale of the Worrell estate see CO 226/88, 248–69, 446–65; for Pope’s views on the defences of P.E.I. see CO 226/102, 294–97. See also: Prince Edward Island, House of Assembly, Debates and proceedings, 1856, 61; 1857, 105; 1863–65, especially 1864, 16; Journals, 1863–65, especially 1864, app.W. Abstract of the proceedings before the Land Commissioners’ Court, held during the summer of 1860 to inquire into the differences relative to the rights of landowners and tenants in Prince Edward Island, reporters J. D. Gordon and David Laird (Charlottetown, 1862), 13, 30, 237 (copies in PAC, PAPEI, and Redpath Library at McGill University).

Islander (Charlottetown), 1859–71, provides the most comprehensive picture of the political positions and attitudes of W. H. Pope. The most valuable source for tracing the progress of the Pope-Palmer delegation of 1863–64 is a series of 19 letters written between September 1863 and February 1864 and published in the issue of 26 Feb. 1864. Pope’s own description of the objectives of the delegation is given in the issue of 21 Aug. 1863. For examples of Pope’s efforts on behalf of confederation see Islander, 10 Feb. 1865, in which he published a lecture he had given on the subject. The issue of 21 June 1867 gives Pope’s opposition to the efforts of the Coles government to obtain a loan in aid of settling the land question. The issues of 24 Nov. and 1 Dec. 1865 explain Pope’s purposes as a member of the 1865–66 delegation to Brazil; see also 18 May 1866 and 19 Feb. 1869.

In 1862 and 1863 the Examiner (Charlottetown) and the Vindicator (Charlottetown) published a considerable number of anti-W. H. Pope articles. Some are interesting and useful for the factual material they contain on Pope’s life, for example, Vindicator, 27 March and 26 June 1863. Its 7 Nov. 1862 issue carried the proceedings of a libel suit launched by Pope against Edward Whelan.

Obituaries of William Henry Pope will be found in Examiner, 7 Oct. 1879; Patriot (Charlottetown), 9 Oct. 1879; Pioneer (Montague, P.E.I.), 10 Oct. 1879; Gazette (Montreal), 20 Oct. 1879 (reprinted from Island Argus (Charlottetown), 14 Oct. 1879, which does not survive).

The main studies of interest include: Bolger, PEI and confederation, which gives a full account of Pope’s role as a father of confederation: see especially 90–99, 113–14, 155–60. Duncan Campbell, History of Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown, 1875).,163–66. Careless, Brown, II, 155, gives George Brown’s impression of the W. H. Pope household. W. L. Cotton, Chapters in our Island story (Charlottetown, 1927), 80, briefly mentions one of Pope’s early business ventures. Creighton, Road to confederation, 13. MacKinnon, Government of PEI. MacMillan, Catholic Church in PEI, chap. 13–17, 20, 23, and 24, give a partisan and sometimes misleading account of Pope’s involvement in the church-state issue. Past and present of Prince Edward Island . . . , ed. D. A. MacKinnon and A. B. Warburton (Charlottetown, [1906]), contains three relevant articles: “The Pope family” (which does not include a consideration of W. H. Pope but provides valuable background material on his family), “W. H. Pope,” and W. L. Cotton, “The press in Prince Edward Island.” Pioneers on Prince Edward Island, ed. Mary Brehaut (Charlottetown, 1959), 13. J. B. Pollard, Historical sketch of the eastern regions of New France, from the various dates of their discoveries to the surrender of Louisburg, 1758: also Prince Edward Island, military and civil (Charlottetown, 1898), 200. [Joseph Pope], Public servant: the memoirs of Sir Joseph Pope, ed. and completed by Maurice Pope (Toronto, 1960), contains several interesting personal sidelights on W. H. Pope. Waite, Life and times of confederation, 8, 51–52, 180. W. M. Whitelaw, The Maritimes and Canada before confederation, with intro. by P. B. Waite (Toronto, 1966), 198. D. C. Harvey, “Dishing the Reformers,” RSCT, 3rd ser., XXV (1931), sect.ii, 37–44, gives an account of the genesis, growth, and eventual death of the system of “non-departmentalism” under which Pope held office for four years. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in PEI,” assesses Pope’s role in the issues centring on religion and education in chap. 4–8; see also 153–54, 166, 167, 174, 289. i.r.r.]

Cite This Article

Ian Ross Robertson, “POPE, WILLIAM HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pope_william_henry_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pope_william_henry_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ian Ross Robertson |

| Title of Article: | POPE, WILLIAM HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |