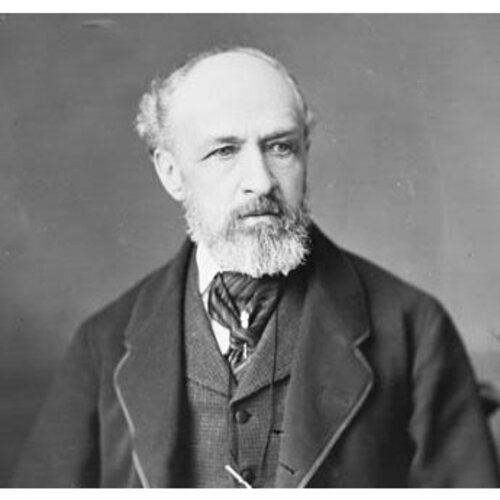

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

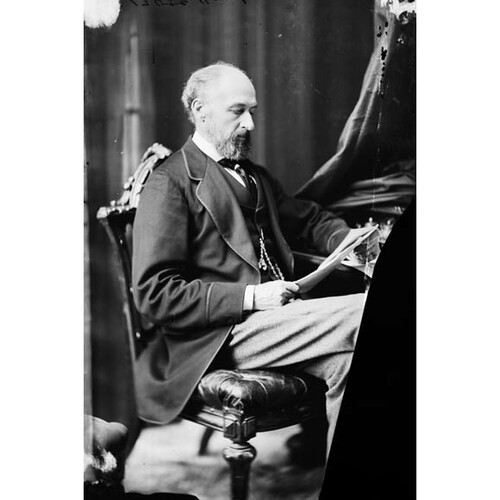

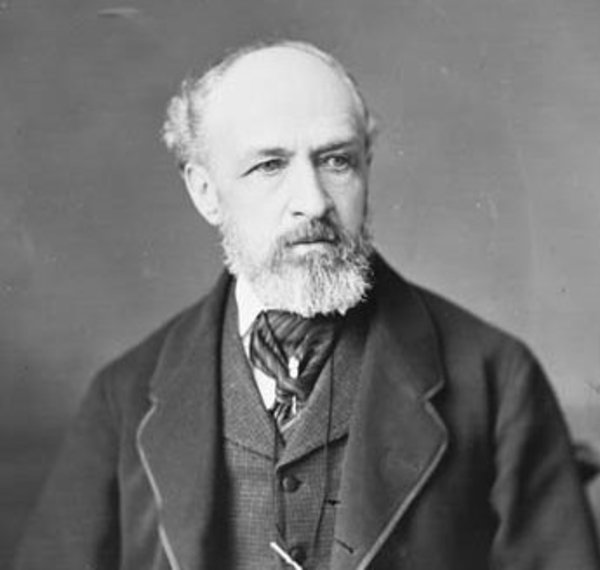

HAVILAND, THOMAS HEATH, lawyer, politician, militia officer, landowner, and lieutenant governor; b. 13 Nov. 1822 in Charlottetown, son of Thomas Heath Haviland* and Jane Rebecca Brecken; m. 5 Jan. 1847 Anne Elizabeth Grubbe, daughter of John Grubbe of Horsenden House, Buckinghamshire, England; d. 11 Sept. 1895 in Charlottetown.

For most of the 19th century, the Haviland name in Prince Edward Island was associated with wealth, political influence, and the tory cause. The elder Thomas Heath Haviland had, after his emigration to the Island in 1816, established himself as an office holder, politician, and landowner. His biographer describes him as “the perfect embodiment of the old régime,” an “elder statesman of the old Family Compact.” His son, Thomas Heath Haviland, was to follow the lead of his father in business, politics, and society. At the time of his death in 1895, in his 73rd year, Haviland Jr was widely regarded as the outstanding member of the old conservative establishment. Ties of church, militia service, business interests, and political outlook had made him a part of an élite group who guided the Island through the confederation era and beyond.

The young Haviland was far from typical among the generation of Islanders born in the early 1820s. His father was rapidly advancing in office, being named to the Council in 1823 and designated colonial treasurer in 1830, and he used his resources and position to advantage in becoming, by the 1840s, a major landowner. As a result, Thomas Heath Jr was sent abroad for a private education in Belgium. The rudimentary educational opportunities of the Island could hardly match the civilizing influence of European schools, at least for those who had sufficient means.

Returning to Prince Edward Island in the early 1840s, Haviland studied law with James Horsfield Peters in Charlottetown. In 1846, at age 24, he was called to the bar and began to practise. Within a year two other foundations of his life were put in place: he married Anne Elizabeth Grubbe and he was first elected to the colonial assembly. His marriage was to produce six children, three boys and three girls. His election began a political career that would span nearly 50 years.

He was returned to the House of Assembly from the Kings County riding of Georgetown and Royalty. The constituency was a natural choice for him since his father was an important landowner in rural Kings, and it was intended that young Haviland should work as an agent on the family lands. He would represent the riding until 1870, when he was elected to the Legislative Council for Queens County, 3rd District. He was returned to the assembly for Georgetown in 1873 and held the seat until 1876. His political leanings were decidedly conservative at a time of increasing agitation for reform and against the Island’s absentee land proprietors. Outside the domestic world of his family and the demands of law and politics, his interests were those one might expect of a maturing member of the Island establishment: the Anglican church and the volunteer militia. He was to be active in the affairs of the church all his life and would become a colonel in the Island militia by the 1860s.

The 1850s brought rapid growth to the Island. Between 1848 and 1861 the population grew from 62,678 to 80,857, and a booming shipbuilding industry and an active agricultural economy were assisted in 1854 by the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States. Political and social change was also on the agenda. The year 1851 saw the grant of responsible government to the colony under a Reform administration headed by George Coles*. In 1852 the Free Education Act was passed, providing public financial assistance to district schools, and the following year brought the Land Purchase Act, by which the government was authorized to purchase, as opportunity arose, estates of more than 1,000 acres and to sell them to tenants and squatters. Both education, particularly the use of the Bible in the classroom, and the land question were to occupy much of Haviland’s political energy during the decade.

On the land question, he was a staunch opponent of those who sought to buy the properties of proprietors at public expense. A spokesman for the landlords, he protested strongly against the purchase in 1854 of the 81,303-acre estate of Charles Worrell*. Joining issue in the assembly with William Cooper*, the former leader of the Escheat party, Haviland maintained in 1857 that he would “never consent to tax the present freeholder, who has acquired his farm by persevering industry, and hard labour for the exclusive benefit of the lease-holder.” The loan bill to finance the purchase of the estate was, in his view, “a tax laid upon industry for the benefit of laziness,” opposed by “all the intelligence and wealth of the country.” This and all other “class legislation” had to be vigorously resisted.

If anything, the Bible question was even more divisive than the land issue. By the late 1850s, Protestant demands for the reading of Scripture in classrooms, fuelled by religious and ethnic divisions, and used by Edward Palmer* and the conservatives as a weapon with which to flay the Coles government, came to dominate the political agenda. Roman Catholics and their bishop, Bernard Donald Macdonald*, opposed compulsory reading of the Bible in a school system that was religiously mixed. Haviland led the tory attack in the assembly. Claiming that the Catholics would be “satisfied with nothing but a godless system of education,” he objected that “education of my children will do more harm than good, unless it is religious.” Although Haviland argued that he “would not tyrannize over Catholics,” his arch-rival Cooper accused him of “sowing . . . seeds of jealousy, strife, hatred and malice.” The intemperate language was a symptom of the time and the issue. In 1859 the Coles government went down to defeat and an all-Protestant conservative administration headed by Palmer came to power. The 37-year-old Haviland joined the government as colonial secretary, and one of its most forceful spokesmen.

The 1860s and early 1870s were a period in Island life dominated by the question of confederation, the land issue, and the barely submerged debate on religion and education. Haviland was to be a leading actor throughout the decade. He was a member of the legislature for the entire period, serving in the Executive Council from April 1859 to November 1862, for a short period in 1865, from 1866 to 1867, and from 1870 to 1876. During most of his time in the government he held the post of colonial secretary, except during 1865 when he was solicitor general. In 1863 and 1864 he served as speaker of the assembly, and from 1867 to 1870 he was leader of the opposition. In and out of government, there was no more articulate and able debater in the house than Haviland. His friends sought his influence and patronage; his political foes often wilted under his wit and force of argument.

The decade of the 1860s was significant in personal terms for Haviland as well. The last of his six children was born in 1860, his law practice prospered, and he became a prominent player in the life of Charlottetown. By 1864 he was lieutenant-colonel of the Queens County Regiment of the volunteer militia, governor and trustee of Prince of Wales College, and trustee of the Lunatic Asylum. He was often to be seen about his law office on Water Street or his fine home on Upper Prince Street. With the death of his father in 1867, the family lands and business interests came formally under his control.

Haviland entered the 1860s profoundly fearful of what the rupture in the American republic might imply for British North America. Speaking in the house in favour of a bill to grant £400 to the volunteer militia in 1862, his scepticism about the republic surfaced. “Let us thankfully contrast our privileges with those of the people in the United States, where the press is shackled, editors imprisoned and Habeas Corpus unconstitutionally suspended,” he argued, pointing to the need for strong colonial militias to fend off a potentially hostile United States. Yet he was also distrustful of proposals for a closer association with other British North American colonies. Maritime union, for example, drew his fire. “Never,” he was reported by the Islander to have said in 1863, would he “sell his birth-right for a mess of pottage.” On the question of free trade with Canada, an issue in the house during 1862, Haviland spoke at length against any such scheme. Fiscal responsibility, if nothing else, inclined him against free trade, for the Island needed every possible source of revenue. “The people,” he noted, “expect to get everything without having to pay for it.”

Confederation, however, was a different matter. When, at Charlottetown in 1864, the attention of Maritimers was turned to the possibility of a broader federation, Haviland became perhaps the most ardent and consistent of the Island confederates. Wider nationhood, economic growth, and defence against the republic were the main elements of his rhetoric. In Charlottetown he proclaimed that “the Provinces would, ere long, be one great country or nation, from the Pacific to the Atlantic.” In Quebec, as a delegate from the Island, he was warmly received in a banquet speech when he proclaimed, “The despotism now prevailing over our border was greater than even that of Russia . . . Liberty in the States was altogether a delusion, a mockery and a snare. No man there could express an opinion unless [he] agreed with the opinion of the majority.” He concluded by emphasizing his belief in the power of railways, “an iron band . . . to unite the colonies.” As Island sentiment, encouraged by Coles, Palmer, and Andrew Archibald Macdonald*, turned against the confederation scheme, Haviland’s views remained firm. In the debates in the assembly in 1865, he again touched on the menace to the south. “It is to my mind very evident,” he chided his reluctant fellow Islanders, “that we must choose between consolidation of the different provinces and colonies, and absorption into the American Republic.”

The admonishments of Haviland and the rest of the small confederate group on the Island notwithstanding, the Island chose a separate course. His labour on behalf of the cause, however, never really ceased. Throughout the late 1860s he dismissed the insularity of the Island as misdirected and argued for the federation of the colonies as a path to a new, broader national spirit. When the Union Association of Prince Edward Island was formed in January 1870, he became its first president, with Joseph Pope as his vice-president.

Confederation was not the only matter preoccupying Islanders at this time. Once again the question of religion and education emerged as an explicit issue, its revival initiated by Bishop Peter McIntyre’s request in 1868 for public funding of Roman Catholic schools. It had, in fact, never really disappeared as an implicit problem and was really more central in many ways to Island political life than the confederation debate. Haviland, as before an outspoken participant in the discussions, was sympathetic towards the bishop’s demands. “Mere secular education,” he argued in 1868, “unless founded upon religious instruction, is utterly futile. “Other issues drew his attention as well. The dividing line between private and public affairs was always, for the business-minded politicians of the day, difficult to determine. An example, in Haviland’s case, was the 1868 bill to repeal the act regulating rates of interest. His role as a director of the Bank of Prince Edward Island (of which his father had been president for some years) was at least as important as his public position when he claimed that “the effect of a Usury Law is to drive capital out of the country, for capitalists will take their money to a place where there are no such restrictions.”

The confederation question forced its way back into the limelight in the early 1870s as the Island sank deep into a morass of railway debt. Construction of a line connecting Charlottetown with the eastern and western sections of the colony had begun in October 1871, and the government was soon in difficult financial straits. In February 1873, faced with a possible collapse of the Island’s economy and influenced by Lieutenant Governor William Cleaver Francis Robinson, Premier Robert Poore Haythorne reopened negotiations with the Canadian government on the subject of union. After the defeat of the Haythome administration in the subsequent election, Haviland went with the new premier, James Colledge Pope*, and George William Howlan* to Ottawa in search of better terms, but the die was cast. Except for two members, Cornelius Howatt and Augustus Edward Crevier Holland, the Island’s assembly was resolved to accept confederation. During the final debate on the question in May, Haviland put the matter in a practical perspective: “Unless we accept the Terms now before us and go into Confederation, it will be utterly impossible, with the large debt now thrown upon us to float our Debentures and establish our public credit.” Unable to resist yet another look southward, he also noted that “we may be proud that we are to form part of a Dominion that has a form of government so superior to that of the United States.”

Prince Edward Island entered confederation on 1 July 1873, and Haviland, as his reward for good service rendered, entered the Senate of the dominion in the same year. The railway whistle, which in some ways was the keynote of the confederation debate on the Island, was, in Haviland’s words, “as welcome to him as the song of the robin.” It was certainly a harbinger of change for the Island.

Two of the outstanding issues of the time were settled in 1873 for, as part of the union, arrangements to resolve the land question had been made. What remained was the thorniest question of all, that of the proper relation of religion and education, and it came to the fore in the general election of 1876. The issue in this contest was whether the Island would have a secular public-school system or a system of publicly funded denominational schools. Haviland, in the past a tory and “Biblican” who was not averse to government grants to separate schools, now joined with the Liberal “Free Schoolers” Louis Henry Davies* and Alexander Laird in a campaign against the “Denominationalists” led by J. C. Pope. Davies’s election card claimed that “old party ties have been severed. It is now a question not of men, not of party, but of principle.” Old party ties had, at least, been temporarily set aside. The result was a convincing win for the Davies government, and the passage of the Public Schools Act, 1877, which provided the Island with a much improved, non-sectarian public school system. The matter was resolved, and Haviland’s role in the issue had been critical. Although he did not stand for election himself, he campaigned vigorously and his association with Davies gave credence to the Liberal leader’s claim that the education issue was a bipartisan one. With this accomplishment behind him, Haviland concentrated his attention on federal affairs as senator.

In 1878 Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservative party returned to power in Ottawa, and on 14 July of the following year Haviland was appointed lieutenant governor of Prince Edward Island, succeeding Sir Robert Hodgson*. The role suited him. He was by now an elder statesman in Island politics, with friends on both sides of the house. He was to serve until 1884, enjoying a respite from the rough-and-tumble world of party politics.

In 1886, after the death of Mayor Henry Beer of Charlottetown, Haviland stepped in to serve out the short remaining term of the mayor, following in the footsteps of his father who had worn the chain of office from 1857 to 1867. It was a critical time for the city. The memory of a major smallpox outbreak was fresh, and a city water-works system was thought necessary by all parties. In January 1887 Haviland won election for a full term, promising to develop the city water system as a public enterprise. According to the Examiner, his mayoralty was a “decisive victory for the friends of order and progress.” Haviland was to serve as mayor until ill health forced him to retire in 1893. He could point with some satisfaction to the new City Hall, built in 1888, and an efficient public water system as his legacies.

Thomas Heath Haviland died on 11 Sept. 1895, survived by his wife, three daughters, and two sons, and was buried in the cemetery of St Peters Cathedral. His obituary in the Guardian noted that “the old men of this city and country who have been constantly mixed up with its political history are rapidly passing away. We shall miss them.” In many ways the virtues ascribed to Haviland by the editors who noted his passing were similar to those people had seen in his father. Courtesy, integrity, and a sense of duty and honour appropriate to his station in life were the hallmarks of his life.

PAPEI, RG 6, Bankruptcy Court, Bank of Prince Edward Island, minute-book, 1856–82; RG 18, 1848: 35; 1861: 17. Abstract of the proceedings before the Land Commissioners’ Court, held during the summer of 1860, to inquire into the differences relative to the rights of landowners and tenants in Prince Edward Island, reporters J. D. Gordon and David Laird (Charlottetown, 1862). C. B. Bagster, The progress and prospects of Prince Edward Island . . . (Charlottetown, 1861). P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1857–76. The union of the British provinces: a brief account of the several conferences held in the Maritime provinces and in Canada, in September and October, 1864, on the proposed confederation of the provinces . . . , comp. Edward Whelan (Charlottetown, 1865; repr. Summerside, P.E.I., 1949). Edward Whelan, “Edward Whelan reports from the Quebec conference,” ed. P. B. Waite, CHR, 42 (1961): 23–45. Examiner (Charlottetown), 5 Dec. 1864; 12 Sept. 1866; 10 Sept. 1880; 2, 6, 14 Sept. 1886; 20, 22 Jan. 1887; 12 Sept. 1895. Guardian (Charlottetown), 13 Sept. 1895. Islander, 5 June 1863, 25 Feb. 1865. Patriot (Charlottetown), 12 Sept. 1895. Protestant and Evangelical Witness (Charlottetown), 11 Feb. 1865. CPC, 1877. P.E.I. directory, 1864. Bolger, P.E.I. and confederation. Canada’s smallest prov. (Bolger). Gaslights, epidemics and vagabond cows: Charlottetown in the Victorian era, ed. Douglas Baldwin and Thomas Spira (Charlottetown, 1988). I. R. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in P.E.I.”

Cite This Article

Andrew Robb, “HAVILAND, THOMAS HEATH (1822-95),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 4, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/haviland_thomas_heath_1822_95_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/haviland_thomas_heath_1822_95_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrew Robb |

| Title of Article: | HAVILAND, THOMAS HEATH (1822-95) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 4, 2026 |