Source: Link

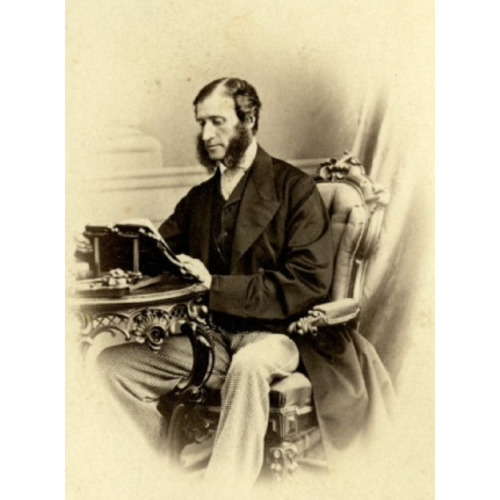

DUNDAS, GEORGE, army officer, politician, and colonial administrator; b. 12 Nov. 1819 in England, first son of James Dundas of Dundas, Scotland, and Mary Tufton Duncan; d. 18 March 1880 on St Vincent in the Windward Islands.

Following completion of his education, George Dundas entered the British army in 1839. He served for five years and during that time was posted to Bermuda and Nova Scotia. After resigning his commission, he was elected as a Tory to the British House of Commons where he sat for Linlithgow from 1847 to 1858. He married Mary Clark in April 1859 (they did not have children), and in the same year embarked upon a new career, as colonial administrator.

When Dundas arrived in Prince Edward Island on 7 June 1859 to take up his duties as lieutenant governor, he was stepping into a delicate position. His four predecessors in office had become openly identified with one party or the other in local politics, with the result that they had been unreservedly abused by whatever section of the factious Island press felt itself to be out of favour. A few months before Dundas’ arrival, the Tories under Edward Palmer* had defeated the Liberals led by George Coles. In his early dispatches to the Colonial Office, the new governor sometimes betrayed a partiality towards the Palmer government and a corresponding irritation with the opposition. He confidently described the Tories as having the support of “far the greatest proportion of the educated and the most respectable classes.” In contrast, he portrayed the Liberal legislative councillors as “obscure, uneducated, and ignorant, selected from the lower classes, irresponsible for their actions.”

In late 1860 Dundas became embroiled in a public controversy with William McGill, a militia officer and former Liberal assemblyman. A group of Roman Catholic volunteers had resigned from their company because of a dispute with their commanding officer, a Captain Murphy, also a Catholic, and had requested that McGill, a Presbyterian, command a new company. Dundas refused to give arms to the new company. McGill took the issue to the public, and chaired a meeting at which Dundas was censured. When the governor, through his adjutant general, Lieutenant-Colonel P. D. Stewart, asked for a retraction, and was refused, he stripped McGill of his rank. McGill responded by publicly accusing Dundas, as an Anglican and a former Tory member of parliament, of having acted out of religious prejudice and political partisanship. Dundas then struck McGill’s name from the list of justices of the peace. In taking these actions, Dundas was widely considered to have exceeded his authority; whether he had done so or not, the whole affair was unfortunate for him, as he subsequently became a target for abuse in the Liberal press.

Edward Whelan*’s Examiner and Edward Reilly’s Vindicator were especially critical of Dundas in 1862 and 1863, when he was caught in the middle of polemical battles between William Henry Pope, the colonial secretary, and Father Angus MacDonald*, the rector of St Dunstan’s College. In June 1862 MacDonald wrote to Dundas and demanded that he dismiss Pope from office for his offensive writings on the Roman Catholic religion. When Dundas, a personal friend of Pope, refused, the rector sent the same request to the secretary of state for the colonies, the Duke of Newcastle [Henry Pelham Clinton]. The latter also declined to intervene officially but did, however, write a private letter to Dundas referring to Pope’s conduct as “disgraceful” and asking the governor to “do all in your power” to terminate the controversy. The vendetta was renewed in early 1863, when MacDonald wrote two more letters to Newcastle, in which he attacked both Pope and Dundas; the secretary of state, weary of the “quarrelsome priest,” again refused to become involved. Although these differences with MacDonald, and related episodes, apparently did not affect Dundas’ standing with the Colonial Office, they led to an intensification of the attacks upon him in the Examiner and the Vindicator. These did not slacken until a general political calm descended late in 1863.

Dundas took an active part in attempts to settle the Island’s land question. In his first year as governor, he intervened personally to ensure that the Selkirk estate was sold to the government rather than to private individuals. George Coles stated in 1869 that “Mr. Dundas had more influence with the proprietors in inducing them to sell, than any Lieut. Governor we ever had.” Nonetheless, in the mid-1860s Dundas was repelled by the radicalism of the Tenant League whose members were pledged to refuse payment of rents. He called the league a “contemptible” organization, led by “senseless demagogues.” He was on leave in Britain when in 1865 the administrator, Robert Hodgson, called in troops to deal with disorders caused by the league. Dundas heartily approved of this vigorous action, and wrote to Edward Cardwell, the secretary of state for the colonies, telling him that he had more than once urged his constitutional advisers to take legal action against Ross’s Weekly, the organ of the league.

When the confederation issue arose, Dundas privately urged the Quebec resolutions upon Island politicians. He fully agreed with his superiors in London in their hope that Prince Edward Island would join the other British North American colonies, and in May 1866 he reported to Cardwell that “at one time I even indulged in the hope that if the other Colonies agreed to terms of Union, I should be able to form a Party [on the Island] to carry it.” This was a vain hope, for in the election of 1867 the Island population strongly supported the anti-confederate candidates running for assembly seats.

George Dundas returned to Britain in October 1868. He never came back to Prince Edward Island, although the decision to transfer him to another posting was not finally taken until the end of 1869. Dundas died in 1880 on the Island of St Vincent where he had been governor for several years.

Dundas’ decade as governor of Prince Edward Island was eventful. He was the object of much criticism, and even abuse, in the early 1860s. This may have been inevitable, considering the verbal violence of Island public life at that time, and the role which his predecessors in office had played in local politics. He failed in his efforts to further the cause of confederation, but public opinion was almost totally opposed to the measure. Despite his hysterical reaction to the challenge of the Tenant League to established authority, he nevertheless appears to have been genuinely concerned with the plight of the tenantry. The judgement rendered in 1863 by Arthur Hamilton Gordon*, then lieutenant governor of New Brunswick, that “Dundas though no Solomon has some quiet sense” seems valid; by the time he left the Island, he had few enemies. Placed in a difficult position, with many pitfalls, Dundas had done a competent job and had won the respect of both Liberals and Conservatives.

University of Nottingham Library, Newcastle mss, Letter books, Colonial correspondence, 1859–64 (microfilm in PAC). PAC, MG 27, I, F2 (Pope papers), George Dundas to James Dundas, 1 Sept. 1863. PRO, CO 226/91–226/104, especially 226/91, 156–63; 226/100, 153–55, 463–66; 226/101, 664–67; 226/102, 160–63; 226/103, 138–39; 226/105, 513–14. Prince Edward Island, House of Assembly, Debates and proceedings, 1869, 131–38, 142–46, 154, 160–61. Examiner (Charlottetown), 13 April 1880. Vindicator (Charlottetown), 1863 – especially important are 6, 13, 20 March, 3, 17, 24 April, 22 May. Bernard Burke, A genealogical and heraldic history of the landed gentry of Great Britain (12th ed., London, 1914), 572. Bolger, PEI and confederation. MacKinnon, Government of PEI. MacMillan, Catholic Church in PEI, 193–206, 231–33. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in PEI,” 78–91, 94–143, 150–54, 157–60.

Cite This Article

Ian Ross Robertson, “DUNDAS, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dundas_george_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dundas_george_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ian Ross Robertson |

| Title of Article: | DUNDAS, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |