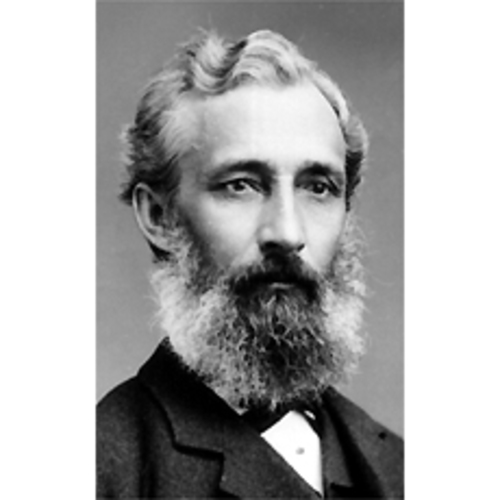

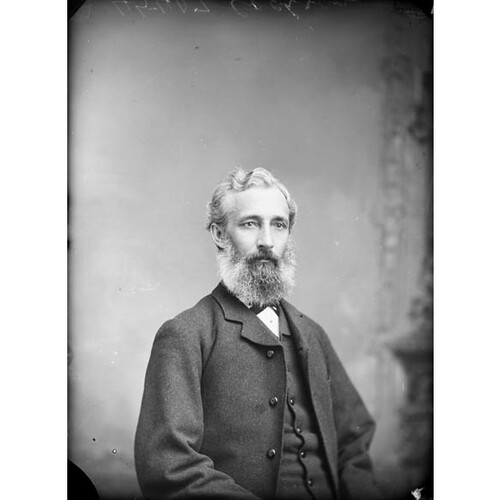

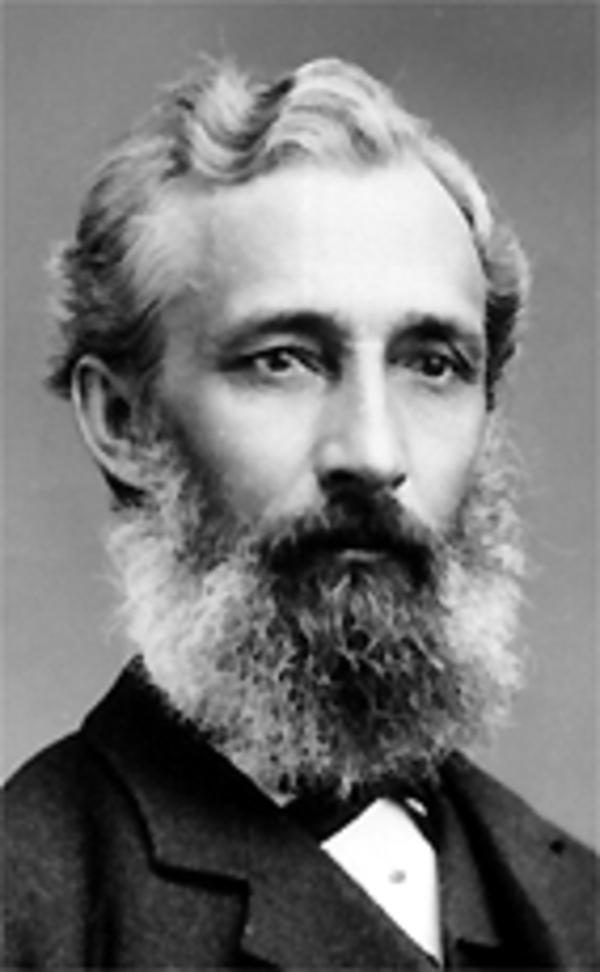

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

COCHRANE, EDWARD, farmer and politician; b. 1 Jan. 1834 in Cramahe Township, Upper Canada, son of James Cochrane and Mary Davis; m. first 5 Aug. 1856 Mary Hicks; m. secondly 29 April 1876 Ellen Louisa Bule, née Thorne; m. thirdly 30 March 1899 Lillian Elucia Odell in Ottawa; he had three daughters and four sons; d. 8 March 1907 in Ottawa.

After establishing himself as a prosperous farmer in Cramahe, Edward Cochrane entered local politics. He held office as school trustee, township councillor, deputy reeve, reeve, and in 1880 warden of the United Counties of Northumberland and Durham. First elected to the House of Commons two years later for Northumberland East, Cochrane, a Conservative, was defeated in 1887 but was eventually returned in a by-election the following year; he gained re-election in 1891, 1896, 1900, and 1904.

Cochrane vigorously supported the administration of Sir John A. Macdonald*. For example, in 1886 he pointed out to the commons the benefits of the National Policy for the agrarian community while loyally ignoring the design’s shortcomings. He was never slavish in backing the Conservative government, however, as is evidenced by his support for John Fisher Wood*’s motion in 1885 that the publication of Hansard be halted, a proposal that was rejected by Macdonald and most Conservatives. Cochrane’s stand flowed from his concern for public economy, which he shared with many other Canadian farmers.

Nevertheless, Cochrane did not endorse the call for independent political action to defend the rural interest that emanated from groups like the Patrons of Industry [see George Weston Wrigley]. Throughout his career the member for Northumberland East would express the agrarian vision, Tory style. The opportunity to do so increased appreciably with the election of Wilfrid Laurier* and the Liberals in 1896. A natural oppositionist, Cochrane was now free to criticize those in power and he castigated the Liberal cabinet for its abuse of patronage, which was used to reward party workers and buy votes, especially in the Maritimes and Quebec. Though he equated Ontario’s interest with the national interest, he argued that federal projects should be important from a dominion, rather than a local, perspective. Parliament should not become a forum for “parish politics.”

Cochrane further denounced the special privileges that some corporations enjoyed through a close association with the Liberals. When new transcontinental railway schemes were put forward by both the Grand Trunk and the Canadian Northern, he asserted in 1903 that the government had “gone mad” in issuing subsidies to railways. As the representative of a rural constituency, he was intent on securing a reduction in the civil service, a larger role for private enterprise, and the use of public tendering as measures to ensure a more economical administration. Cochrane assailed the “hypocrisy” of the Liberals as well as their profligacy. All too often they dismissed criticisms on the flimsy grounds that a policy or practice had been tolerated by their Tory predecessors. According to Cochrane, the government should stand or fall on the merits of its own program. Similarly he felt that it should provide more, and clearer, information to the commons. The voice of the farmer could also be heard in his related demands that legislation, government publications, and the electoral process be simplified in the interests of the average voter.

In presenting these points Cochrane occasionally spoke in a bitterly partisan, and at times rude, fashion. During a debate in 1899 he even threatened to break the nose of a Grit antagonist. On the whole, however, he was well liked and respected on both sides of the house, where he became fondly known as “Uncle Ned.” By mid 1905 he had retired from farming and had moved to Brighton, but he continued as an mp. Political friend and foe alike mourned his passing in 1907 after an extended bout with throat cancer. Though never a leading man on the national political stage, Edward Cochrane was a significant supporting actor, first as a Conservative back-bencher and then as a prominent critic of the Laurier regime.

AO, RG 22, ser.191, no.5887; RG 80-5, nos.1876-007157, 1899-003954. Brighton Ensign (Brighton, Ont.), 8, 15 March 1907. Globe, 10 March 1907. Sentinel (Toronto), 14 March 1907. World (Toronto), 9 March 1907. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1882–1907. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). CPG, 1887–1907.

Cite This Article

Peter E. Paul Dembski, “COCHRANE, EDWARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cochrane_edward_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cochrane_edward_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter E. Paul Dembski |

| Title of Article: | COCHRANE, EDWARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |