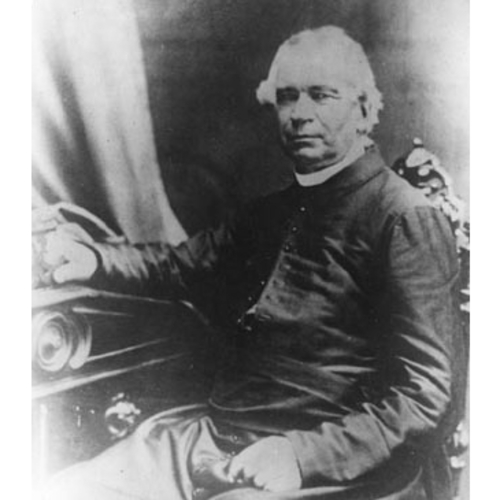

THIBAULT (Thibaud, Thebo), JEAN-BAPTISTE, secular Catholic priest, missionary, founder of the Lake St Anne mission (Alberta); b. 14 Dec. 1810 at Saint-Joseph-de-Lévis, L.C., son of Jean-Baptiste Thibault and Charlotte Carrier; d. 4 April 1879 at Saint-Denis-de-la-Bouteillerie (Kamouraska County), Que.

Jean-Baptiste Thibault, a farmer’s son, received his classical and theological education at the seminary of Quebec, where on 31 March 1833 he was admitted into the subdiaconate. On 28 April he set out for the North-West. Contrary to several of his predecessors, he had no debt to pay before his departure. Yet the Thibault family was scarcely well-to-do, if the sums of money that the bishopric subsequently sent rather often to his father are an indication.

During the voyage, the missionary was frequently shocked by the behaviour of the crew. Unable to quiet them, or to ensure the use of more acceptable language, he complained to the captain. He was sturdy, but, hampered by his timidity, he was unable to enforce respect from those who provoked him. This timidity was to be construed as pride when Thibault, feeling ill at ease with the employees, later refused the hospitality offered at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trading posts. He arrived at Saint-Boniface in June 1833, and began to study the Cree and Chippewa languages. On 8 September he was ordained priest by Bishop Joseph-Norbert Provencher*.

Two years later, in the bishop’s absence, Thibault showed himself to be a wise and skilful administrator of the western missions. The building of the cathedral at Saint-Boniface progressed, and the yield from the farm belonging to the mission increased. Thibault proved to be a good preacher, without being too verbose. Above all, he was good at expounding; this quality was appreciated by Bishop Provencher, who considered that Christianity should be brought to the Indians by persuasion, and not “in the Protestant fashion” by gifts. In such a manner the ministers of the different faiths accused each other of trading in souls.

In 1842, therefore, at the request of the Indians and Métis, Bishop Provencher sent Thibault as a missionary across the prairies to the Rocky Mountains. The bishop made this decision unknown to the HBC, which had refused to approve his plan; Thibault, however, met the preference of the company for Canadian rather than French missionaries. His first journey lasted six months, during which, prudently, he travelled on horseback across the plains as far as Edmonton House – the first Catholic or Protestant missionary to adopt this form of transportation. Delighted with the politeness and cordial welcome extended to him by the commandants of the company’s forts, he preached the gospel to all the Canadiens, Indians, and Métis who came to him. He welcomed the Blackfeet, whom he described thus: “These Indians . . . are very clean, and very well-disposed towards the whites; but their number, their warlike qualities, and particularly their rapacity make them the terror of their redskin enemies. They have only a very imperfect idea of the divinity.” This journey, the prelude to the diffusion of Catholicism throughout the American northwest, bore fruit: Thibault conducted 353 baptisms and celebrated 20 marriages, in addition to acquiring a better knowledge of the religious needs of this vast region.

For 10 years the missionary worked discreetly, without displaying excessive zeal, and visited the meeting-places of the Indians and Métis. Thibault was probably the first Catholic missionary to make his way to several of the HBC posts and to several places where the Oblates were later to establish missions [see Eynard; Reynard]. However, only one foundation is acknowledged unanimously as his, the Lake St Anne mission. Crees were accustomed to stay in this spot, which they called Devil’s Lake; Thibault substituted the name of St Anne. He stayed there in 1842 and 1843, but it was only in the summer of 1844 that a house was built for the missionary.

In 1852, acting on Thibault’s request to return to Quebec, Bishop Provencher recalled him to Red River. When Thibault reached Saint-Boniface, however, Provencher asked him to stay there, as there was no one to minister to the region. Thibault did so, and did not return to the diocese of Quebec until 1868.

While at Quebec in the autumn of 1869, Thibault was visited by Hector-Louis Langevin*, who asked him to go to Red River as a representative of the Canadian government. Thibault was believed to have a great influence over the Métis. Some of them had just refused to allow William McDougall*, who had been appointed lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories by the Canadian government, to enter the settlement. By this action the Métis and their leader, Louis Riel*, meant to force the federal government to negotiate with them the terms of their union with Canada. Conjointly with Charles-René-Léonidas d’Irumberry* de Salaberry, Thibault was to reassure them that Ottawa intended to respect their rights and not to treat them as a conquered people, and to convince them to lay down their arms [see Sir John Young]. A third delegate, Donald Alexander Smith*, was for his part to set at rest the minds of the company’s directors, and to discuss with all “the people of Red River” the conditions of their entry into the dominion. The prime minister, John A. Macdonald*, judging Thibault to be “a sensible old French Canadian” and “a shrewd and at the same time a kindly old gentleman,” was of the opinion that, if he accomplished nothing in particular, at least he would not commit any blunders since he knew the region and supported the Canadian government. A reserved and prudent man, Thibault was content to remain in the background, and this was where circumstances kept him during his governmental mission.

Salaberry having remained at Pembina, Thibault, on 25 December, arrived in the west alone. By order of the recently proclaimed provisional government, Thibault was escorted to the bishop’s palace at Saint-Boniface, where he was kept under surveillance so that he would not meddle in political affairs. On 6 Jan. 1870 Louis Riel and his council received Thibault and also Salaberry, who had just arrived. “Immediately we communicated our instructions to the president [Riel] and his council,” Thibault recounted, “and they took them under consideration.” However, no comment was received, and four days later Thibault wrote to the provisional government to ask about the conditions required by the colony in the event of its union with Canada, “in order that we can submit them,” he said, “to the examination of the government that sent us.” The next day the council replied to him that the documents Thibault and Salaberry had submitted did not confer on them the necessary powers to conclude an agreement. On 13 January the council expressed this opinion to Thibault and Salaberry by word of mouth. According to the commissioner D. A. Smith, Thibault ceased to be useful from then on. In general, historians agree that he had no influence on the course of events. But Smith wrote that had it not been for the steps Thibault took during the night of 19–20 January, he himself would have succeeded in settling everything at this time. During that night, as Smith has it, Thibault contributed to a closing of the ranks of the demonstrators, who that day had held public meetings which Smith’s money and promises had managed to break up. Subsequently Riel’s position grew stronger, and he became formally president of the provisional government, whose bases were enlarged. Then delegates were sent to Ottawa to negotiate the entry of the Red River colony into confederation [see John Black]. Was Thibault partly responsible for this sudden change? In his report, he said that he had had “to reason with the leaders, and with the people; always, however, by conversations with single individuals, as that seemed to me the best . . . way of effecting any good result.”

Thibault stayed two more years at Red River, ministering to the parish of Saint-François-Xavier; then in 1871 he accepted the post of vicar general of the diocese. The following autumn he returned to the east for good, and was successively in charge of the parishes of Sainte-Louise (L’Islet County) and Saint-Denis-de-la-Bouteillerie.

A man of little ambition, Thibault preferred to work in a parish where he could follow the instructions of a bishop, for he did not like to direct affairs himself. Although he spent the greater part of his life in the diocese of Saint-Boniface, he was of the opinion, as early as 1856, that secular priests should withdraw from that region. As a missionary, Thibault opened up the way to the west and north in America; as a government emissary, he defended the interests of those whom he was supposed to appease.

AAQ, Registre des lettres des évêques de Québec, 15, p.367; Rivière-Rouge et diocèse de Saint-Boniface (Man.), III, 161. ACAM, RLL, 5, p.383; RLL, 7, p.132; 255.109. ANQ, Collection Chapais, Fonds Langevin, Jean Langevin à Hector-Louis Langevin, 5 janv. 1870, Taché à Cartier, 15 mars 1870. Archives de l’archevêché de Saint-Boniface (Man.), Documents historiques, 1861–1872. ASQ, Séminaire, XXXVIII, 7, 9. PAC, MG 17, B2, C.1/M-C.1/M10; MG 26, A (Macdonald papers), 101, pp.40831, 40833, 41082, 41083, 41086, 41198; 516, pp.614–17, 646–51, 666–69, 717–18, 939–41; RG 6, C1, 10A, p.1041. PAM, Louis Riel papers; Red River Settlement, Copies of miscellaneous letters and documents, 92. ... Begg’s Red River journal (Morton), 81, 82, 88–91, 239, 240–50, 268, 289, 299, 301, 454, 468, 482, 533, 535. Canadian North-West (Oliver), II, 907–8. [P.-J. De Smet], Life, letters and travels of Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J.,1801–1873 . . . , ed. H. M. Chittenden and A. T. Richardson (4v., New York, 1905), IV 1560. Hargrave, Red River, 129, 135. HBRS, XXII (Rich), 917, 921–22, 932. James Wickes Taylor correspondence (Bowsfield), 97. Paul Kane, Wanderings of an artist among the Indians of North America . . . , intro. and notes by L. J. Burpee (Master-works of Canadian authors, ed. J. W. Garvin, VII, Toronto, 1925; repub. with intro. by J. G. MacGregor, Edmonton, 1968), 261, 276. “Lettres de Monseigneur Joseph-Norbert Provencher, premier évêque de Saint-Boniface, Manitoba,” Bulletin de la Société historique de Saint-Boniface, III (1913), 137, 138, 147, 154, 167, 173, 179, 195, 196, 234–35, 246, 247–48, 249–50, 256–57. McLean’s notes of twenty five years service (Wallace), 123, 318–19. [A.-A.] Taché, Vingt années de missions dans le Nord-Ouest de l’Amérique (Montréal, 1866; New York, 1970), 4, 20, 57–58, 64–66, 86, 88, 222, 238. ... Allaire, Dictionnaire. Morice, Dict. hist. des Can. et Métis, 297. Julienne Barnard, Mémoires Chapais: documentation, correspondance, souvenirs (4v., Montréal et Paris, 1961–64), III, 18–19, 156. F. E. Bartlett, “William Mactavish, the last governor of Assiniboia,” unpublished ma thesis, University of Manitoba, 1964. J.-É. Champagne, Les missions catholiques dans l’Ouest canadien (1818–1875) (Publ de l’Institut de missiologie de l’université pontificate d’Ottawa, I, Ottawa, 1949), 64–65. Georges Dugas, Histoire de l’Ouest canadien de 1822 à 1869; époque des troubles (Montréal, [1906]), 154; Monseigneur Provencher et les missions de la Rivière-Rouge (Montréal, 1889). Donatien Frémont, Monseigneur Provencher et son temps (Winnipeg, 1935). Giraud, Le Métis canadien, 1074–81. Morice, Hist. de l’Église catholique, I, 234; II. Alexander Ross, The Red River Settlement; its rise, progress, and present state . . . (London, 1856; Minneapolis, 1957), 275–300. Stanley, Birth of western Canada, 88–91, 93–96, 121, 146, 148; Louis Riel, 85. Gaston Carrière, “L’honorable compagnie de la Baie d’Hudson et les missions de l’Ouest canadien,” Revue de l’université d’Ottawa, XXXVI (1966), 15–39, 232–57. C. J. Jaenen, “Foundations of dual education at Red River, 1811–1834,” HSSM, Papers, 3rd ser., no.21 (1965), 35–68. G. F. G. Stanley, “Louis Riel,” Canada’s past and present; a dialogue, ed. R. L. McDougall, (Toronto, 1965), 21–40..

Cite This Article

Lionel Dorge, “THIBAULT (Thibaud, Thebo), JEAN-BAPTISTE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thibault_jean_baptiste_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thibault_jean_baptiste_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lionel Dorge |

| Title of Article: | THIBAULT (Thibaud, Thebo), JEAN-BAPTISTE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |