Source: Link

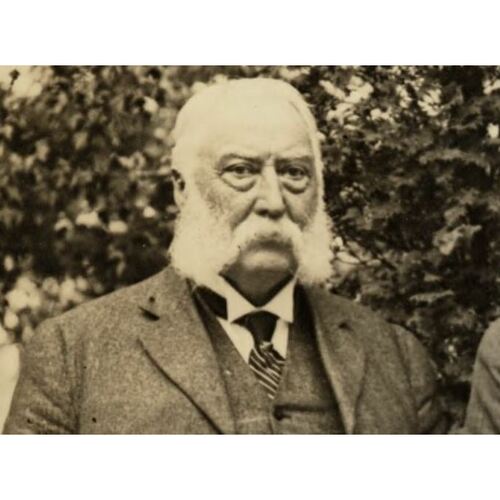

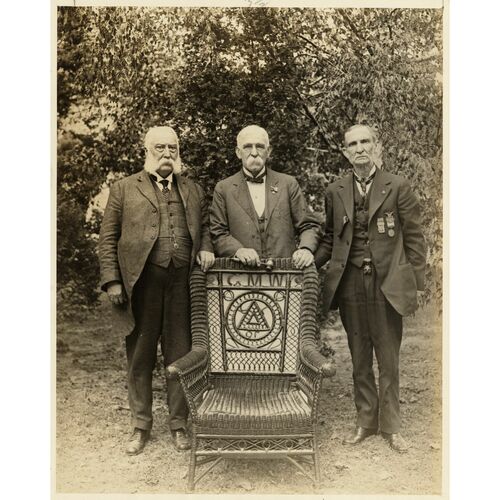

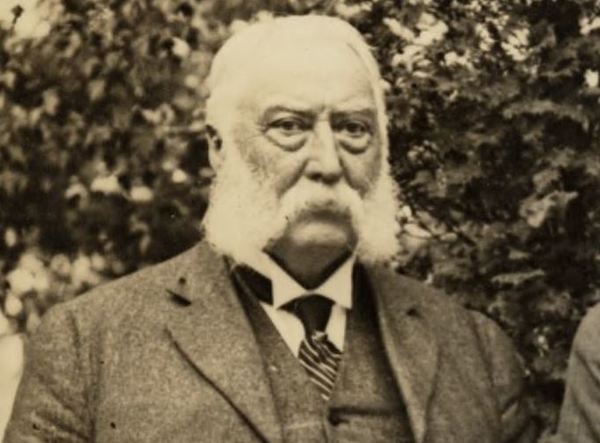

WRIGHT, ALEXANDER WHYTE, militiaman, journalist, labour leader, reformer, office holder, and political organizer; b. 17 Dec. 1845 in Upper Canada, son of George Wright and Helen Whyte; m. 26 Jan. 1876 in Guelph, Ont., Elizabeth Runciman Simpson (d. 1913), and they had a daughter; d. 12 June 1919 in Toronto.

The son of Scottish immigrants, A. W. Wright was probably born near the settlement of Almira in Markham Township, though some sources give his birthplace as Elmira in Waterloo County. He attended public school in New Hamburg in the 1850s and after brief employment as a drugstore clerk he entered the woollen industry, in which his family was engaged. He started in 1863 in Linwood and subsequently worked in Preston (Cambridge), St Jacobs, and Guelph. Active in athletics and lacrosse in his youth, he joined the Orange order and the Waterloo militia. He saw action with the 29th (Waterloo) Battalion of Infantry against the Fenians in 1866 and participated in the Red River expedition of Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley in 1870–71 as a sergeant-major in the 1st (Ontario) Battalion of Rifles.

Sometime in the late 1860s Wright became a printer. He started his career in journalism with the Guelph Herald and progressed to editorial positions with the Orangeville Sun, the Stratford Herald, and County of Perth Advertiser, and the Guelph Herald. As an editor and Tory fixer, he promoted nationalism and industrial development but combined them with an inclination to radical economic solutions involving government ownership, and currency and labour reform. Wright advanced these positions not only in print, but as a highly skilled platform speaker. In the federal by-election in Guelph in 1876, for instance, he spoke on behalf of the Conservatives’ protectionist candidate, James Goldie. “When dealing with a subject with which he was familiar,” wrote one biographer, “he was unsurpassed. He had bright, incisive style and a talent for keen analysis. He was at his best when heckled. He courted interruption, for no one could get the better of him in a clash of wits.”

After he moved to Toronto in 1878 as editor of the National, Wright used it to promote the National Policy of Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald*. Perhaps the most intellectually interesting of the plethora of Toronto newspapers of the 1870s, the National had been the vehicle for prominent radical Thomas Phillips Thompson*. Both he and Wright were heavily influenced by the producer ideology of Isaac Buchanan* of Hamilton. Indeed, Wright worked as a pro-protection lecturer for Buchanan’s Dominion National League in the National Policy election of 1878. In the aftermath of the Tory victory, Wright schemed with Buchanan to imbue the Workingmen’s Liberal Conservative Union with the ideas of currency reform and government ownership. In a typical attempt to bridge the leadership of the Conservative party and the members espousing reform ideology, Wright sought Macdonald’s support for both the National and his proposal to author a popular biography of the prime minister. Neither scheme came to fruition.

The financial difficulties of the National led Wright and his partner, Henry Edward Smallpiece, to take over the Guelph Herald in the summer of 1879. As its editor and co-producer, Wright promoted a scheme to have the Canadian Pacific Railway built publicly through a complicated mechanism of financing that involved radical currency reform. In addition, he joined Buchanan in reorganizing the Financial Reform League of Canada as the Currency Reform League, of which he became secretary and William Wallace* chairman. Still active in the WLCU, Wright continued his efforts to use this innovative Tory organization to transform the working-class vote into a vehicle for his radical ideas, including advocacy of the Beaverback cause, a Canadian variant of the American greenback movement and an amalgam of protection for native industry, the government’s resumption of the right to issue monetary notes, and a system of paper money based on the credit of the dominion. After Wright returned to Toronto in 1880 to edit the Commonwealth, a Beaverback paper that promoted land, labour, and currency reform, he gained the backing of the WLCU for his Beaverback candidacy in the federal by-election in Toronto West. Although he won only a little more than one per cent of the vote, Wright’s independent stand prefigured labour’s political challenges to Tory hegemony in Toronto during the 1880s.

After stumping through the northeastern and mid-western United States for the National Greenback Labor campaigns later in 1880, Wright came back to Toronto to become an editorial writer at the Tory World. As secretary of the Ontario Manufacturers’ Association in 1882–86, he worked hard for the Tory party in traditional ways. In 1885, with publisher Frederic Nicholls*, he compiled a commemorative volume on the massive conventions held to honour Sir John A. Macdonald’s 40 years in public life. But Wright also continued to focus his attention on the working-class vote. In the following decade, he would emerge as the main Canadian leader of the Knights of Labor, the major North American reform organization; in the process Wright would help undercut the labour revolt of the 1880s in Ontario and aid in the restoration of the Tory party’s working-class base. How he arrived at these ends is a complex reconstruction of back-room intrigue, at which Wright became a master.

In 1883 Wright had joined the Knights, probably Excelsior Local Assembly 2305, since it was the only local in Toronto to encompass various occupations. In June 1886 he switched to the new Victor Hugo Local Assembly 7814, which featured mainly journalists and other “brainworkers” and included figures such as Phillips Thompson and Wright’s brother-in-law and fellow journalist, Robert Lincoln Simpson.

Wright’s profile in the Knights remained low until 1886. Upon his return that year from Europe, where he had represented Canada as a government agent at expositions in Antwerp and London, he set out to activate schemes he had proposed two years earlier. In 1884 he had suggested to Prime Minister Macdonald that, if given adequate financial support, he could arrange to take over one of the new labour reform newspapers. Like many of his schemes, this one did not find initial favour, but during the bitter Toronto Street Railway strike of 1886, in which Tory interests were damaged by the involvement of Frank Smith*, a Conservative senator, Wright began publication on 15 May of the Canadian Labor Reformer, with R. L. Simpson and George Roden Kingsmill as managers. Although Wright proposed to Macdonald that it “be conducted editorially on a purely labour platform, even antagonizing the Conservative Party where it could be done harmlessly,” ultimately, he said, “it would do good” for the party.

Wright went even further, and devised stratagems to weaken the Knights’ Grit-oriented Local Assembly 2305, controlled by Daniel John O’Donoghue*. He suggested the establishment of a Toronto district assembly of the Knights, a proposition denounced by O’Donoghue as potentially divisive. Wright was successful, however, and District Assembly 125 was chartered on 17 May, at the height of the street railway strike. Not surprisingly, Wright was elected secretary, from which position he launched the next phase of his career in labour reform.

The Ontario election of late 1886 and the federal election of early 1887 were hard-fought affairs in which the working-class vote was hotly contested. As well, a number of labour reform candidates ran and, at the Ontario level, enjoyed some success. Political intrigue was rife and Wright was at the centre. In the provincial election, claiming to be a labour candidate supported by the Knights, he ran unsuccessfully in Lambton West against Liberal cabinet minister Timothy Blair Pardee*. In the aftermath of these elections, a war of accusations concerning partyism rose in a crescendo as O’Donoghue, in the pages of his Labor Record, and Wright, in his Labor Reformer, denounced each other. The cause of independent labour politics was the major casualty.

Wright none the less continued to scheme. With Samuel McNab, the district master workman of District Assembly 125, he promoted the idea of a Canadian general assembly separate from the American-based General Assembly that governed the entire order. First proposed by Hamilton District Assembly 61 in 1885, the idea resurfaced in January 1887 when London District Assembly 138 went on record in support of a Canadian assembly. American general master workman Terence Vincent Powderly fuelled this nationalist sentiment when he unthinkingly urged all Knights to celebrate the 4th of July in 1887. In September Knights from all over Ontario met in Toronto at the call of Wright and McNab to discuss “Home Rule.” The convention endorsed the creation of a dominion assembly, with the proposition to be taken to the Knights’ General Assembly in Minneapolis that fall. Powderly, however, forewarned by O’Donoghue, derailed the movement by conceding the idea of provincial assemblies for Ontario and Quebec and a legislative committee to lobby in Ottawa. In a determined effort to keep his rival off this committee, O’Donoghue suggested that Powderly appoint Wright instead as a lecturer for the Knights.

Powderly acted on this recommendation the following year and Wright became lecturer and examining organizer for Ontario. At the General Assembly of 1888, in Indianapolis, he captured Powderly’s trust, gained election to the general executive board (the first Canadian to achieve such high office in the order), and thereafter displaced O’Donoghue as Powderly’s major Canadian adviser. In his new role Wright made sure that the new Canadian legislative committee did not contain any hold-overs from the previous year. By late 1890 the order in Canada was in disarray and Powderly eventually allowed the legislative committee to lapse.

Charges and countercharges of partisanship and of “politicians in the Order” were certainly among the causes of its decline in Canada, and Wright played a prominent role in this mêlée, which helped eliminate the Knights as the major political voice of organized labour. As editor of the Journal of the Knights of Labor (Philadelphia) from 1889 and as a member of the general executive board, he participated too in the destructive leadership battles that tore the order apart in the United States and led to Powderly’s downfall at the General Assembly of 1893. Indeed, Wright’s various moneymaking schemes, such as the Labor Day annual and an accident claims association, his laxness as editor, and a certain looseness in his accounts of his personal finances all became issues in the struggle for control between Powderly and John W. Hayes. The triumph of the latter brought Wright’s opportunism and role in the order to an end.

Wright continued to plot with Powderly and others to regain control, but nothing came of these manœuvres. Similarly, his efforts to launch a newspaper in labour’s interest, but funded by the Republican party, were unproductive. He busied himself in the Ontario election of 1894 with support for the agrarian revolt of the Patrons of Industry [see George Weston Wrigley*], no doubt (at least partially) because of the havoc it would wreak on the Grit government of Sir Oliver Mowat*. Wright’s pen, partially disguised by the pseudonym Spokeshave, promoted agrarian dissent in the Canada Farmers’ Sun until he abandoned the cause to return to Tory ranks in 1896.

Wright would trade on his labour connections for the rest of his life. In October 1895 the federal Conservative government of Sir Mackenzie Bowell appointed him lone royal commissioner to investigate the sweating system in Canadian industry. A series of public meetings exposed evidence of horrific conditions in the garment trades. Issued in March 1896, a few months before a federal election, Wright’s report called only for the extension of provincial factory acts to cover all places of work, including homes, where outwork was performed. The Conservatives, who had reputedly set up the commission for electioneering purposes, declined to act, and there were even charges that Wright campaigned for the party during or just after the inquiry.

Later in 1896 Wright worked as a propagandist in the presidential campaign of William McKinley in the United States. Recommended by Powderly, he was placed in charge of economic materials aimed at the working-class vote. The following year he appeared in New York City as editor of the Union Printer and American Craftsman. Before long he was again recruited by the federal Tory party in Canada: in July 1899 he became one of three organizers in Ontario, with responsibility for the southwestern part of the province. And once again Wright became deeply involved in intrigue. He supported his old journalist mate William Findlay Maclean* in his efforts to challenge the provincial Tory leader, James Pliny Whitney, and arrest what they saw as a “policy of drifting” in the Ontario party. By the summer of 1901, however, Wright, working out of a home in Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake), was using his exceptional skills to ensure Conservative victories in several key ridings in the next provincial election. Three years later Robert Laird Borden*, the Conservative leader in Ottawa, appointed Wright and a long-time organizational cohort, Thaddeus William Henry Leavitt, to turn their attention to federal organization in Ontario.

After this employment, Wright remained on the public stage. A strong proponent of public control of hydroelectric development and the refining of nickel, from 1907 he championed “People’s Power” as president of the Canadian Public Ownership League. The politically astute Wright had little sympathy for supporters, among them Francis Stephens Spence, who saw the cause as a means to moral reform, in forms such as temperance. In the provincial election of 1908 Wright ran as an independent in Toronto West on a slate that included socialist, labour, Liberal, and Conservative candidates, and on this occasion he finished third, with 21 per cent of the vote. In his campaign literature he described himself as a Liberal Conservative who supported the Whitney government, although some elements of his platform, including public control of nickel refining, citizens’ initiation of and voting on legislation, civil service and tax reform, and enactment of workmen’s compensation, went beyond government policy at that time.

After a sojourn in Britain in 1910–11 as a propagandist for imperial preferential trade, Wright returned to Canada. Here he publicly turned his advocacy of imperial unity against reciprocity in the federal election of September 1911 and appeared as a Conservative speaker in the provincial election in December. When he was not deriving income from his public and organizational efforts, Wright seems to have found periodic employment in journalism and business. In 1909–14 he edited a Tory labour newspaper, the Toronto Lance, and in 1912 he was manager of the Toronto Fire Brick Company Limited. The Whitney government rewarded his many years of service in 1914 by appointing him vice-chairman of the new Workmen’s Compensation Board. He never completely recovered from a slight stroke suffered in 1918 in Niagara-on-the-Lake and he died the following year at his home on Macdonell Avenue in Toronto. A Presbyterian, he was buried in Prospect Cemetery.

Wright’s career took him from small-town Ontario to the heights of North American labour reform as a major leader of the Knights of Labor. A man who lived by his wit and writing, in all aspects of his life he delighted in intrigue and manipulation. The Orangeism and militarism of his youth were two of his major identifications and they flowed easily into his support for the Conservatives. Although his economic beliefs encompassed a certain radicalism, he almost always placed party loyalty first. An important Canadian example of a mediator who linked the working class and the traditional political party, he exemplifies that strain of Canadian conservatism which espoused reform.

Alexander Whyte Wright’s papers are preserved in NA, MG 29, A15. His publications include Report of the demonstration in honour of the fortieth anniversary of Sir John A. Macdonald’s entrance into public life . . . (Toronto, 1885), compiled with Frederic Nicholls (incorrectly attributed in CIHM, Reg., to Arthur Walker Wright); Knights of Labor, District Assembly 125, Report of A. W. Wright, delegate from DA 125 to the Philadelphia session of the General Assembly, Knights of Labor (Toronto, 1894; copy in his papers); Labor Day annual (Philadelphia), 1893, prepared with T. V. Powderly; Report upon the sweating system in Canada (Ottawa, 1896); and Confidential letter to Liberal-Conservative workers: Toronto, May 1st, 1902 (Toronto, 1902), co-written with T. W. H. Leavitt. Wright is also the author of an unpublished paper on “County Waterloo’s part in the Fenian raids” (typescript, n.d.), available in his papers at the NA.

AO, RG 22-305, nos.27800, 38540; RG 80-5-0-61, no.11971. Catholic Univ. of America (Washington), Dept. of Arch. and mss, John W. Hayes papers; T. V. Powderly papers. NA, MG 24, D16; MG 26, A. Canada Farmers’ Sun (Toronto), 1894–96. Canadian Labor Reformer (Toronto), 1886–87. Commonwealth (Toronto), 1880. Guelph Herald (Guelph, Ont.), 20 Nov. 1879. Journal of the Knights of Labor (Philadelphia), 1889–93. Lance (Toronto), 1908–15. National (Toronto), 1874–80. Stratford Herald, and County of Perth Advertiser (Stratford, Ont.), 2 Feb. 1876. World (Toronto), 13 June 1919. Canada investigates industrialism: the royal commission on the relations of labor and capital, 1889 (abridged), ed. G. [S.] Kealey (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1973), 65–68. Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1904, 1907–8, 1910–14. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan, 1898 and 1912). Paul Craven, “An impartial umpire”: industrial relations and the Canadian state, 1900–1911 (Toronto, 1980). Directory, Toronto, 1902. C. W. Humphries, “Honest enough to be bold”: the life and times of Sir James Pliny Whitney (Toronto, 1985). G. S. Kealey, Toronto workers respond to industrial capitalism, 1867–1892 (Toronto, 1980; repr. 1991). G. S. Kealey and B. D. Palmer, Dreaming of what might be: the Knights of Labor in Ontario, 1880–1900 (Toronto, 1987). B. D. Palmer, A culture in conflict: skilled workers and industrial capitalism in Hamilton, Ontario, 1860–1914 (Montreal, 1979). W. J. Rattray, The Scot in British North America (4v., Toronto, 1880–84). Who’s who and why, 1919/20. J. [S.] Willison, Reminiscences, political and personal (Toronto, 1919).

Cite This Article

Gregory S. Kealey and Christina Burr, “WRIGHT, ALEXANDER WHYTE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 16, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wright_alexander_whyte_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wright_alexander_whyte_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gregory S. Kealey and Christina Burr |

| Title of Article: | WRIGHT, ALEXANDER WHYTE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 16, 2025 |