Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

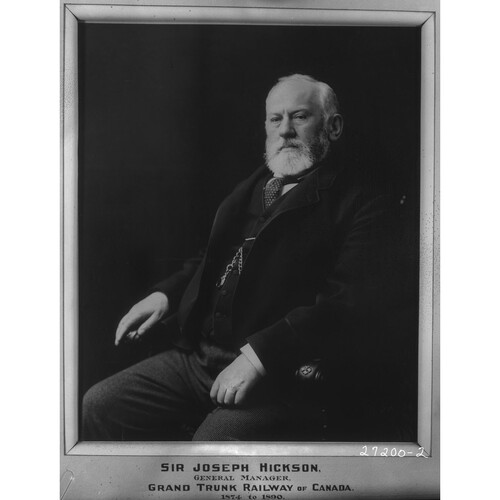

HICKSON, Sir JOSEPH, railway official and jp; b. 23 Jan. 1830 in Otterburn, Northumberland, England, second son and fourth child of Thomas Hixon, a smith, and Ann Brodie; m. 17 June 1869 Catherine Dow in Montreal, and they had three sons and three daughters; d. there 4 Jan. 1897.

Joseph Hickson received a good but abbreviated education, and at a young age became an office clerk for the York, Newcastle, and Berwick Railway. In 1851, after a brief stint with the Maryport and Carlisle, he moved to the Manchester, Sheffield, and Lincolnshire Railway, where he rose to assistant manager. During this period leading companies consolidated their empires amid cutthroat competition, and the professional railway manager emerged to solve the problems posed by large business organizations. On the Manchester, Sheffield, and Lincolnshire, Hickson worked with two of the more dynamic and successful of these men, James Joseph Allport, manager from 1851 to 1853, and Edward William Watkin, his successor. In 1861 Watkin, a man of large ambition, boundless energy, and creative vision, became president, residing in London, of the Britishowned Grand Trunk Railway in British North America, and that December he engaged Hickson as chief accountant. Hickson took up his post in Montreal in early 1862.

Conceived in 1851 by Francis Hincks* as a trunkline uniting the British North American colonies, the Grand Trunk had been put together by the amalgamation of existing lines and the construction of long sections joining them [see Sir Casimir Stanislaus Gzowski]. By 1859 it was completed from Sarnia, Upper Canada, to the Atlantic Ocean at Portland, Maine, and in 1860 an extension was added in Lower Canada from Lévis to Fraserville (Rivière-du-Loup). Inflated construction costs, overestimated revenues, and an inadequate initial capitalization had quickly put the line into severe financial difficulty. To head off collapse, Watkin attempted to fuse, under his control, the Grand Trunk and two other roads, the Great Western [see Charles John Brydges*] and the Buffalo and Lake Huron [see Edmund Burke Wood*]. He failed, but Hickson helped to negotiate a lease of the Buffalo and Lake Huron in 1864 that provided the Grand Trunk with an American outlet at Niagara Falls, N.Y., and allowed it to compete with the Great Western for American through traffic from Michigan to New York. Hickson early understood the significance for the Grand Trunk of American business.

Hickson also realized the importance for his career of consolidating his position. In addition to performing his accounting duties diligently, he ensured that monies received from the government by the Grand Trunk for the transportation of troops and mail went directly to the British postal bondholders, and for this service they quietly paid him £200 per annum. In 1865 he was made secretary-treasurer of the railway, a post that gave him greater scope for administration. Five years later he was promoted lieutenant-colonel of the 1st Battalion (Garrison Artillery) Grand Trunk Railway Brigade, an ad hoc unit formed in February 1867 to defend the railway from possible attacks by Fenians; his commission was backdated for rank and precedence to March 1867. His advances in the firm notwithstanding, Hickson worked in the combined shadow of Watkin and Charles John Brydges, the general manager since 1862, both of whom concentrated authority in their own hands. However, although aggressive administrators, they were unable to make the Grand Trunk turn a profit. As a result Watkin resigned under shareholder censure in 1868, and Brydges followed under a similar cloud in 1874. Hickson succeeded Brydges.

Meanwhile, in London, Watkin’s successor, Richard Potter, had been embracing the trend towards devolution of authority that was taking place on many large American railroads. Indeed, he had called for Brydges’s resignation in part because Brydges had refused to delegate authority. To avoid centralization of control under Hickson, Potter granted a newly appointed traffic manager, Lewis James Seargeant, considerable independence and permitted four other officers to attend meetings of the railway’s executive council as consultants. Hickson headed the council and could outvote all others present, but, a student of Allport, Watkin, and Brydges, he chafed at having to listen to “subordinate officers officially criticizing . . . their immediate and responsible superior.” Consulting the executive council, he asserted, was a waste of time. Disenchanted by Hickson’s attitude, Potter also considered that the general manager did not provide the board in London with sufficient operational detail. Hickson bided his time until, in 1876, Potter’s authority was shaken by a conflict between himself and the prime minister of Canada, Alexander Mackenzie, who was supported by the railway’s principal bondholders, the London banking houses of Glyn, Mills and Company and Baring Brothers. When Hickson supported the bankers and threatened resignation, the board refused to support Potter, who then resigned. He was succeeded by Sir Henry Whatley Tyler, with whom Hickson soon enjoyed a close working relationship.

His authority consolidated, Hickson confronted his first crisis in management-labour relations late in 1876. Traditionally Canadian railways had provided employment for skilled workers during slack periods in order to guarantee a loyal work force for prosperous times. By the 1870s an abundance of qualified workers seemed to make harsher tactics feasible. Beset by falling revenues as a result of severe depression, strong competition, and rising maintenance costs, Hickson abandoned the paternalistic practice. In the spring of 1875 he fired 625 men from the mechanical and engineering departments and attempted to lower the wages of the senior locomotive drivers. The engineers, members of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, an American union, resisted. Wary of their strength, Hickson accepted a return to the status quo through a written agreement, one of the first in railway labour history. It signalled a further movement away from a paternalistic to a corporate labour system. Continued decline in revenues, however, prompted Hickson to try again in November 1876. He ordered all wages cut by ten per cent and all unnecessary employees dismissed. By Christmas Eve 150 engineers had been fired. The rest struck, and for 108 hours the Grand Trunk ran no through trains. Hickson lobbied federal, provincial, and municipal governments for military and police aid, but the responses, particularly in Ontario, were negative or slow in coming for jurisdictional reasons and because the railway, considered haughty and unresponsive to local needs, was widely unpopular. Hickson could not afford a long strike, and he accepted a new agreement which restored, with several changes, that of 1875. Thereafter he relied on a mixture of corporate paternalism and selected wage cuts to conciliate and dominate the brotherhood. When, in 1886, following two years of wage reductions, the engineers mounted strong resistance, he reinstated the old rates, made additional corporate contributions to the company’s insurance and pension fund, which had been instituted in 1873, and permitted employees to sit on the council administering the fund. Hickson’s willingness to avoid prolonged confrontation sets him apart in the generally bloody and bitter world of late-19th-century North American railway labour relations.

Hickson had assumed managerial control of the Grand Trunk at a time of great consolidation among North American railways. Rate and traffic consortia, composed of many relatively small and independent roads, were being superseded by amalgamations under unified managements. This development permitted dramatic reductions in maintenance and managerial costs and facilitated a general upgrading of rolling stock. The result was a quicker and more efficient movement of traffic and hence lower rates. Aware of these trends, and of the fact that the Grand Trunk was in position to be a connecting line from Chicago to the Atlantic Ocean, Hickson advised his directors in June 1876 to acquire independent access to Chicago by purchasing the Chicago and Lake Huron Railroad, a patchwork system that ran through Michigan. Hitherto the Grand Trunk had relied on the Michigan Central Railroad for such access, and in 1875 it had generated 25 per cent of the Grand Trunk’s freight revenue. But the Michigan Central played off the Grand Trunk against two competitors, the Great Western and the Canada Southern Railway, and Hickson judged further reliance on it unwise. His course required cash, however, and the Grand Trunk had none. Over the next two years he kept close watch on the constituent elements of the Chicago and Lake Huron. When the Vanderbilt family, owners of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, sought secure access to Chicago by purchasing the Canada Southern, the Michigan Central, and a middle component of the Chicago and Lake Huron system, Hickson, supported by Tyler, swung into action. He sold the Grand Trunk’s Rivière-du-Loup extension, which was dead weight, to the government-owned Intercolonial Railway for $1,500,000 and purchased lines at each end of the Vanderbilts’ Chicago road. He then threatened to build a parallel line in the middle, forcing the Vanderbilts to sell their interests in the Chicago road to the Grand Trunk in 1880. He consolidated the new properties as the Chicago and Grand Trunk Railway and reaffirmed an alliance he had with the Vermont Central Railroad in the east. That year some 40 per cent of the Grand Trunk’s receipts originated from Chicago. In appreciation the shareholders of the Grand Trunk presented Hickson with a table service in gold and silver worth £2,500.

Content with their access to Chicago, Hickson and Tyler had no desire to build north of Lake Superior to the Canadian west. They initially supported government-subsidized construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which was chartered in 1881, in the belief that a “collision of interests” could be avoided by making Lake Nipissing, Ont., the CPR’s eastern terminus, or at the very least by limiting the CPR east of that point to a single trunk line. In either case the Grand Trunk would provide all linkages east of Lake Nipissing. However, the aggressive general manager of the CPR, William Cornelius Van Horne*, realized that no line which had to run over railways “having adverse interests” could be successful, and the CPR sought to expand in the east. Hickson protested bitterly to Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald that public funds were being used to enable the CPR to compete with the private British investment behind the Grand Trunk. The president of the CPR, George Stephen*, charged that Hickson wanted “universal dominion” in the east, and Van Horne coined the phrase “Hicksonizing the Government” in reference to his incessant lobbying. Hickson was, in fact, on friendly personal terms with Macdonald. He may even have had some electoral influence; the Grand Trunk had always supported the Conservatives by ordering its employees to vote for them, and in the elections of 1882 Macdonald exhorted Hickson to “put your shoulder to the wheel and help us.” Upset by Macdonald’s commitment to the CPR, he hesitated, but in the end he came through; a train was furnished to Macdonald for the campaign, won by the Conservatives. Macdonald continued to support the CPR, however, and he sought to alienate Hickson from Tyler, who was actively prejudicing British investors against the CPR; the general manager remained staunchly loyal to his president. In London in April 1883 Tyler reached an agreement with Stephen that promised to end the conflict, but the mercurial Stephen was quickly persuaded by his New York and Canadian advisers to renounce the accord. In February 1884, in an effort to influence a crucial debate on financing the CPR, Hickson published his correspondence with Macdonald on that subject. As late as October he and Van Horne had yet to meet, let alone seriously discuss their profound differences.

During the 1880s Hickson and Van Horne backed up their rhetoric with swift acquisitions and hectic construction. Although forced by the government to sell the North Shore Railway and thus permit the CPR to have an independent line between Montreal and Quebec, Hickson acquired 250 miles of railway in Quebec and Michigan and consolidated his command of the Vermont Central Railroad. Most of his activity occurred in Ontario, however. There, between 1881 and 1890, he took control of 15 companies – including the Grand Trunk’s strongest rival until then, the Great Western – adding 1,900 miles of track to the Grand Trunk system. Perhaps the most successful of his moves occurred in 1888 when, after a decade of quiet bond buying, he formally took over the Northern Railway system, which ran from Hamilton to Nipissing Junction. This acquisition gave the Grand Trunk access to the CPR line at Nipissing Junction and forestalled an attempt by Van Horne to acquire an independent connection between Toronto and the CPR’s mainline. It also gave the Grand Trunk a charter to build from Callander to Sault Ste Marie and thus improve its position to challenge for the CPR’s western trade. As Van Horne lamented to Macdonald, “More than half our traffic to and from the North West goes to or comes from Ontario and the Grand Trunk now stands between us and that.” In addition Hickson instituted construction of the St Clair Tunnel at Detroit, a major engineering feat completed in 1890 with a federal subsidy of $375,000, and the double-tracking of the Montreal–Toronto line, completed in 1892.

Despite Hickson’s efforts, the CPR gained access to Chicago and Montreal with the aid of the federal government and of New York capitalists, including the Vanderbilts, whom Hickson termed his “most bitter opponents.” With some justification he complained to Macdonald that the CPR had been “created for one object” but “is to be employed for another.” His protests were to no avail; by 1885 the CPR was firmly entrenched in Ontario, the Grand Trunk’s backyard.

The CPR’s administrators labelled Hickson’s expansive policy “insane” and a product of “inordinate conceit and vanity.” It was hardly that. His actions reflected his training and the often wastefully competitive capitalist milieu within which he operated. A shrewd negotiator (Stephen complained that “he always wants a little more than is quite fair”) and an aggressive competitor, he elicited praise from Chicago businessmen for fracturing the Vanderbilt monopoly and, along with Tyler and the Grand Trunk management generally, he enjoyed an excellent reputation in the United States for competence and honesty. At the same time as he was expending enormous sums to fight off the intrusion of the CPR, he was exhibiting great skills in managing the Grand Trunk’s finances. He persuaded holders of higher priced but less stable securities to exchange them for four per cent debenture stock, and by 1890 these exchanges were saving the firm £80,000 a year. In addition he made real estate deals that were shrewd financially and politically, while his management of the railway’s investments, placed largely in other railways, not only earned the company £72,000 per annum but gave him excellent leverage in negotiations.

Although much less popular in Canada than in the United States, Hickson had his admirers there as well. Among them was James Ferrier*, a Montreal businessman who in 1886 urged Watkin and Tyler to seek tangible recognition of his contribution. Watkin asked Macdonald to recommend a knighthood, but the prime minister hesitated, invoking possible cabinet opposition. As well, Macdonald reminded Watkin, “Hickson . . . considers himself part & parcel of the GTR,” and because the government had supported its rival, “the toes of the GTR have been trodden on – and Hickson feels it as if his gouty foot had been Crushed.” There were rumours, he added, that the employees of the Grand Trunk would be ordered to vote Liberal; Watkin was invited to “deal with this matter quietly for us.” By January 1887 Macdonald had been reassured of the Grand Trunk’s loyalty, but when he offered to recommend a knighthood Hickson refused. He bitterly maintained his refusal despite pressure from Ferrier and company officials until, in November 1888, he was induced to accept for the benefit of the railway. The honour was finally conferred on 20 Jan. 1890.

The board of directors of the Grand Trunk was not as enchanted with Hickson’s management as were Ferrier and Watkin. In the end, he had neither stopped the CPR in the east nor made the Grand Trunk profitable. Having continued as treasurer of the company, he had prepared accounts in a manner designed to preclude any precise assessment of the financial impact of his costly expansive policies. At the same time he had failed to seek funds to modernize running equipment and upgrade general maintenance, so that the Grand Trunk laboured under an operational disadvantage vis à vis many of its American competitors, which had modernized. In December 1890, less than 12 months after he had been knighted, the board obtained his resignation and replaced him with Lewis James Seargeant. Watkin, unable to imagine Seargeant’s “little feet” in Hickson’s “big shoes,” offered to buy up sufficient stock to enable Hickson to counter-attack. At the age of 60, however, Hickson was perhaps a tired fighter; in return for a retainer of £1,000 a year (reduced in 1896 to £500) he agreed to render advice on request and remain loyal to the railway. His advice was never requested, but he did remain faithful.

Hickson had taken few holidays while with the Grand Trunk, and those were usually spent quietly on his farm in Cacouna, Que. Although he had been a justice of the peace in Montreal since 1865, was a member of the St George’s Society, and was active in the affairs of St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, he had had, and continued to have, little time or, perhaps, disposition for public work. He was, however, generous in his assistance to English immigrants, and in 1892 he sponsored a house of refuge for destitute French immigrants to Montreal. That year Macdonald appointed him chairman of a royal commission on the liquor traffic, which in 1895 reported at length on the conduct of the liquor trade, recommended regulations, and calculated the social and other consequences of prohibition. According to a contemporary, Lady Hickson was active in numerous charities and occupied “a high social position in the commercial metropolis.”

Sir Joseph Hickson died from “paralysis” in early January 1897. On the eve of his resignation as general manager of the Grand Trunk he had written to Macdonald respecting the railway to which he had devoted much of his life without stint: “Results have been required which are impracticable.” It would have made a fitting epitaph.

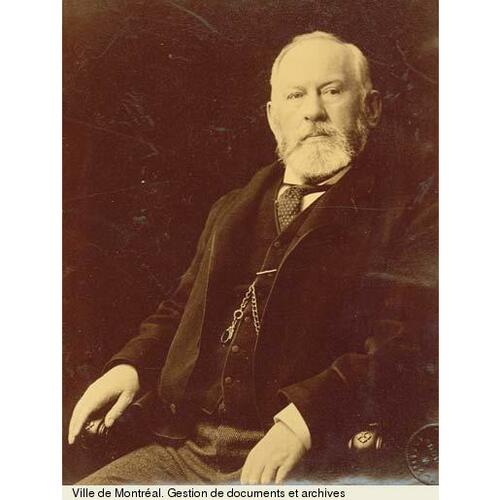

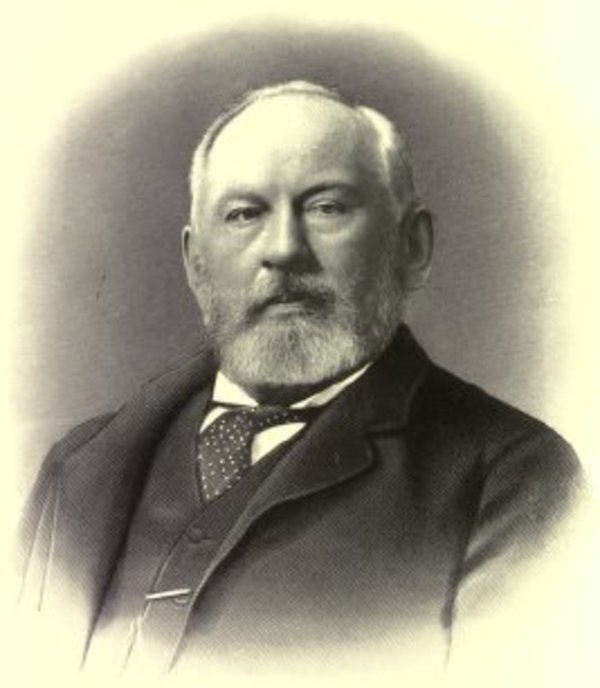

The correspondence exchanged by Joseph Hickson and Sir John A. Macdonald in 1884 regarding government help to the Canadian Pacific Railway was published by the Grand Trunk Railway as Grand Trunk Railway: correspondence between the company and the dominion government respecting advances to the Canadian Pacific Railway Company (n.p., [1884]). A portrait of Hickson appears in George Stewart, “Sir Joseph Hickson,” Men of the day: a Canadian portrait gallery, ed. L.-H. Taché (32 ser. in 16v., Montreal, 1890–[94]), ser.29: 449–57, and another is in Railway Journal (Montreal), 11 Nov. 1881.

ANQ-M, CE1–125, 17 juin 1869, 8 janv. 1896. NA, MG 26, A, 130, 139–40, 191, 220, 223, 228, 259, 267, 269, 272, 360, 524, 526, 529–30; MG 27, 1, D8; MG 28, 11120, Van Horne letter-books, 1–36; MG 29, A29; RG 30, IA, 1, vols.1028, 1039–43; 4, vol.10201; RG 68, General index, 1841–67. Northumberland County Record Office (Newcastle upon Tyne, Eng.), Birdhopecraig Presbyterian Church, reg. of births, 23 Jan. 1830. J. [A.] Macdonald, Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald . . . , ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1921), 449–50. Proceedings of a conference between Sir Joseph Hickson, Mr. W. C. Van Horne and a sub-committee of the joint committee re esplanada (n.p., [1890]). Globe, 5 Jan. 1897. Montreal Daily Star, 4 Jan. 1897. Railway Times (Boston), 1870–90. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth). Types of Canadian women (Morgan), 157. A. D. Chandler, The visible hand: the managerial revolution in American business (Cambridge, Mass., 1977). Paul Craven and Tom Traves, “Dimensions of paternalism: discipline and culture in Canadian railway operations in the 1850s,” On the job: confronting the labour process in Canada, ed. Craig Heron and Robert Storey (Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1986), 47–74. A. W. Currie, The Grand Trunk Railway of Canada (Toronto, 1957). C. H. Ellis, British railway history: an outline from the accession of William IV to the nationalisation of railways . . . (London, 1954). T. R. Gourvish, Mark Huish and the London & North Western Railway: a study of management (Leicester, Eng., 1972). H. J. Perkin, The age of the railway (Newton Abbot, Eng., 1971). G. R. Stevens, Canadian National Railways (2v., Toronto and Vancouver, 1960–62). P. J. Stoddart, “The development of the southern Ontario steam railway network under competitive conditions: 1830–1914” (ma thesis, Univ. of Guelph, Guelph, Ont., 1976). P. [A.] Baskerville, “Americans in Britain’s backyard: the railway era in Upper Canada, 1850–1880,” Business Hist. Rev. (Cambridge, Mass.), 55 (1981): 314–36. Jacques Gouin, “Histoire d’une amitié: correspondance intime entre Chapleau et De Celles (1876–1898),” RHAF, 18 (1964–65): 364. Desmond Morton, “Taking on the Grand Trunk: the locomotive engineers strike of 1876–7,” Labour ([Halifax and Rimouski, Que.]), 2 (1977): 5–34.

Cite This Article

Peter Baskerville, “HICKSON, Sir JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hickson_joseph_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hickson_joseph_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter Baskerville |

| Title of Article: | HICKSON, Sir JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 25, 2025 |