Source: Link

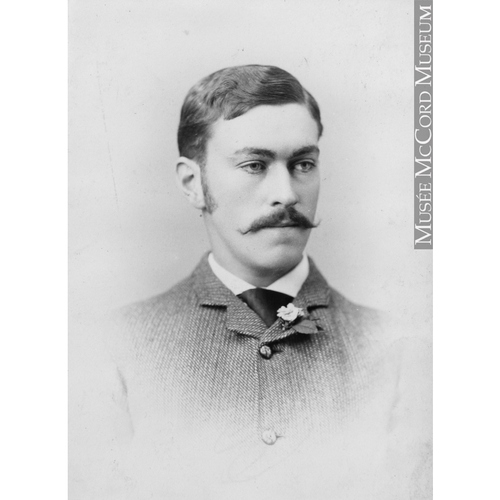

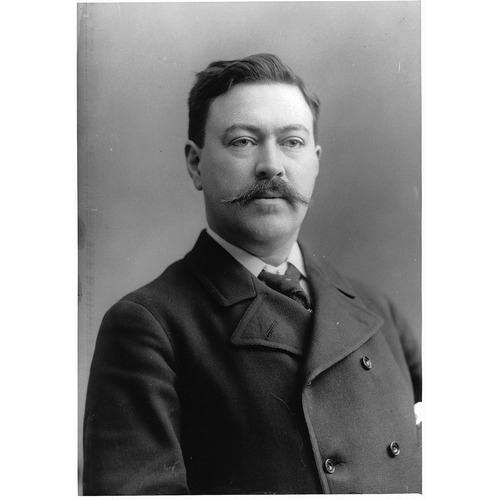

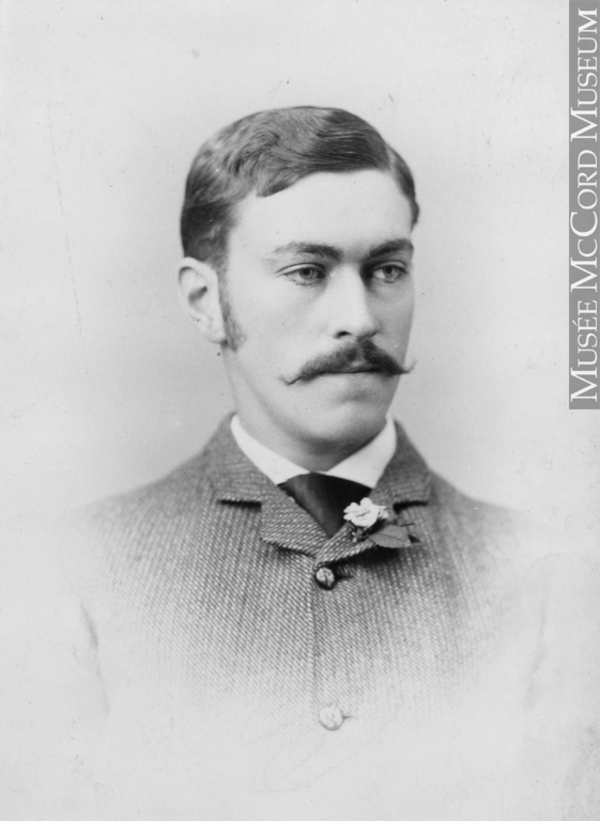

DRUMMOND, GEORGE EDWARD (known as George Edward Drumm until 1875), businessman, author, and consul general; b. 21 Oct. 1858 in Tawley (Republic of Ireland), son of George Drumm, a constable, and Elizabeth Morris Soden; m. 20 Feb. 1890 in Brantford, Ont., Elizabeth Foster Cockshutt, daughter of Ignatius Cockshutt* and Elizabeth Foster, and they had two sons and two daughters who survived him; d. 17 Feb. 1919 in London, England.

George Edward Drummond came to Montreal in 1864 with his parents and his three brothers, William Henry*, John James, and Thomas Joseph. Despite his father’s premature death two years later, he was able to study at the Royal Arthur School in that city. On completing his education, he was hired by the Montreal metal-importing firm of A. and C. J. Hope and Company [see Adam Hope*]. It was there, in the late 1870s, that he met his future business partner, James Tod McCall.

In 1881, without their employer’s knowledge, Drummond and McCall decided to establish their own enterprise, hoping to become the exclusive agents for a large iron and steel company in Glasgow with which they had already been in contact. The Canadian economy was recovering from the crisis of 1873 and the ensuing six years of recession. Furthermore Sir John A. Macdonald*’s Conservative government had just announced its intention to finance the construction of a transcontinental railway, and there were prospects of lucrative contracts for the supply of rails and other iron materials. Against this background Drummond, McCall and Company, commission merchants, was founded in August 1881. It did not take long to prove itself. Three years later its capital had increased from $400 to $5,000, and its sales had reached $30,000. Two factors appear to have contributed significantly to the partners’ initial success: the excellent quality of the Calder cast iron imported from Scotland, and their good fortune in being able to retain many of the customers they had dealt with at A. and C. J. Hope. In 1884 Thomas Joseph, George Edward’s younger brother, joined the firm. Located in a building on Custom House Square near the port of Montreal, it imported not only pig-iron ingots, but also cutlery, tools, wrought iron items, steel rails, faucets, and hydrants, which constituted a highly profitable business for them. In 1885 Drummond, McCall and Company were the exclusive representatives in Montreal for 12 British iron and steel manufacturers, including three in Scotland. Through W. Heybrock Jr and Company of Amsterdam they were also agents for coffee merchants. They sold their stocks of metals to Montreal nail makers such as the Pillow and Hersey Manufacturing Company Limited and the Montreal Rolling Mills Company, and to producers of boilers, motors, and farm machinery in Ontario.

In 1888 the two Drummonds went into partnership with Patrick Henry Griffin, from Buffalo, N.Y., a manufacturer of railway-car wheels, to establish the Montreal Car Wheel Company Limited. With an initial capital of $75,000, the new enterprise intended to offer vigorous competition to the near-monopoly enjoyed by John McDougall* in the Montreal market for such wheels. In the suburb of Lachine the partners built a small complex of shops in which some 100 skilled workers (casters, machinists, and others) were soon employed. However, the high cost of pig-iron from the United States prompted them in short order to buy a blast-furnace so that they could control the price and quality of this raw material more effectively. In 1889 George Edward Drummond and five other partners, including McCall, established the Canada Iron Furnace Company with a view to buying the Radnor ironworks [see Auguste Larue*], which was owned by the estate of George Benson Hall*. The transaction was concluded that year in return for assumption of the estate’s debts. The Radnor iron and steel complex included a charcoal blast-furnace in the village of Fermont (Saint-Maurice), a spur line connecting the village to the Les Piles railway, mining rights in the region of Lac à la Tortue (which was rich in bog iron), timber rights on the crown lands at Grandes-Piles, and a railway-wheel foundry in Trois-Rivières. After managing to assemble a large amount of capital from local and foreign investors, in 1892 the owners of Canada Iron Furnace undertook to build a new blast-furnace on the site of the Radnor ironworks at a cost of $165,000. George’s elder brother John James was put in charge of drawing up plans and supervising construction. Using the technical experience he had gained in American ironworks during the 1880s, he built a 40-foot-high charcoal blast-furnace with an opening nine feet wide, the largest of its kind in North America. At the same time the steam-driven bellows of the old furnace was replaced by a Weimer compression motor, making increased production possible. According to estimates, the Radnor ironworks produced more than 7,423 tons of charcoal cast iron in 1893. At peak periods the complex employed about 850 men, of whom at least 700 were farmers from the neighbouring area hired to rake up the ore in the bogs, cut wood and make charcoal, or transport raw materials. A bad fire in 1896 seems not to have affected the company, which continued to expand with George Edward as its administrative manager.

From 1895 to 1909 Drummond wrote many articles on the state of the metallurgical industry in Canada. Most of these came out in the Canadian Mining Review (Ottawa) or the Canadian Mining Institute’s Journal (Ottawa and Montreal). His growing reputation in the field of iron and steel production earned him one of the vice-presidencies of the institute in 1899–1900 and 1908–9.

At the end of the 19th century, under Drummond’s management, Canada Iron Furnace undertook to branch out into Ontario. In 1899 the decision was made to invest in the construction of a huge charcoal blast-furnace in Midland, on Georgian Bay. According to its promoters, the new plant would raise Canada to the level of Sweden as a world producer of iron and steel. The furnace, which went into operation the following year, could produce up to 80 tons of cast iron a day. In 1901, however, the plant had to be converted to use coke, probably because of the excessively high cost of charcoal. In 1902 Canada Iron Furnace built a foundry in Fort William (Thunder Bay) in an attempt to dominate the market for water mains and railway-car wheels in western Canada. This plant joined the company’s wholly owned foundries in Hamilton and St Thomas in Ontario, Montreal and Trois-Rivières in Quebec, and Londonderry in Nova Scotia.

That year Canada Iron Furnace bought the old blast-furnace of the Londonderry Iron Company. It was renovated to raise its productive capacity to 100 tons of cast iron a day. In this transaction the company had joined forces with the late John McDougall’s descendants, who also owned iron and steel complexes in Drummondville and Saint-Pie-de-Guire. Drummond was still managing director on the board of Canada Iron Furnace, which had nine members, three from the United States, two from Ontario, and four from Montreal.

The wind began to shift, however, at the beginning of the 20th century. For one thing, production methods using charcoal were proving increasingly expensive in comparison with those using coke. Then, too, modern chemistry was providing a glimpse of the paramountcy that steel would enjoy in the near future. The Radnor ironworks began to slow down in 1906 and finally closed four years later. It was also significant that in 1908 Canada Iron Furnace and the McDougall family’s Canadian Iron and Foundry Company merged to form a powerful consortium, the Canada Iron Corporation Limited. The result of an effort to consolidate the assets of the primary iron and steel sector in Canada, it brought together five mines, five coke blast-furnaces, and numerous foundries located in seven towns and in two provinces. In spite of everything, the corporation had to liquidate its property in 1913 in order to pay off its creditors, the principal one being the Montreal Trust Company, of which Drummond was a director. It seems that he later tried to revive a number of pipe foundries with varying degrees of success. He remained at the head of Drummond, McCall and Company and had begun to shift his investment portfolio into the financial sector. In 1912, for example, he sat on the boards of directors of the Liverpool and London and Globe Insurance Company, the Montreal Trust Company, and the Molsons Bank.

In the course of his career Drummond had also made a name for himself as a talented lobbyist. In the commercial sphere, he was an ardent champion of the National Policy implemented by the Macdonald government in 1879. He credited the new 1887 tariff scale with the success of Montreal producers in taking over one-sixth of the Canadian market for primary iron and steel. When Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals came to power in 1896, he made no secret of his apprehension about Canada’s commercial policy and the future of the industry. In 1905, as president of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association (he had been elected in September 1903), he reiterated his belief in a coercive tariff policy with regard to American manufacturers, although he still favoured reciprocal preferential tariffs with Britain. His address to the members, which was published at Toronto as a brochure entitled West and east: their interests identical, gives a good summary of his point of view on the question. His expertise in the field of international trade also brought him appointment in 1909 as consul general of Denmark in Montreal. In his political stands, Drummond usually adopted the imperialist ideas characteristic of the Tories. For example, at the fifth Congress of Chambers of Commerce of the Empire, held in Montreal in 1903, it was he who had a resolution adopted in favour of a colonial contribution to Britain’s defence effort.

Well known as an Anglican who was thoroughly committed to his church and a philanthropist who supported numerous causes – as his membership in many associations demonstrates – Drummond loved sports too, especially fishing. Towards the end of his life he often went to England as a delegate to conferences on imperial trade. He died in London on 17 Feb. 1919, leaving two sons and two daughters in mourning.

[The author wishes to thank historian René Hardy of the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières for allowing him to consult the files of the Centre de Recherche sur l’Évolution de la Sidérurgie Québécoise au XIXe Siècle.

George Edward Drummond is the author of a number of pamphlets on subjects that interested him, such as the iron and steel industry, Canadian commercial policy, and imperial defence, including Early days of iron industry in the province of Quebec (Montreal, [1893]; repr. [1951]); The iron industry; what it is to Great Britain and the United States; what it may be to Canada . . . ([Montreal?, 1894?]); and West and east: their interests identical ([Toronto, 1905]), which originally appeared in Industrial Canada (Toronto). r.t.]

AC, Montréal, Cour supérieure, déclarations de sociétés, 9, no.1021 (1881); 16, no.488 (1892); 29, no.41 (1908). AO, RG 80-5-0-175, no.1396. NA, MG 28, I 394; MG 30, A88, 1. Gazette (Montreal), 25 Feb. 1919. Montreal Daily Star, 18 Feb. 1919. The book of Montreal, a souvenir of Canada’s commercial metropolis, ed. E. J. Chambers (Montreal, 1903), 206. J. D. Borthwick, History and biographical gazetteer of Montreal to the year 1892 (Montreal, 1892). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Canadian mining manual . . . (Ottawa), 1894–96, 1901–3. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Jean Hamelin et Yves Roby, Histoire économique du Québec, 1851–1896 (Montréal, 1971). René Hardy, La sidérurgie dans le monde rural: les hauts fourneaux du Québec au XIXe siècle (Sainte-Foy, Qué., 1995). K. E. Inwood, The Canadian charcoal iron industry, 1870–1914 (New York, 1986).

Cite This Article

Robert Tremblay, “DRUMMOND (Drumm), GEORGE EDWARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drummond_george_edward_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drummond_george_edward_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Tremblay |

| Title of Article: | DRUMMOND (Drumm), GEORGE EDWARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |