Source: Link

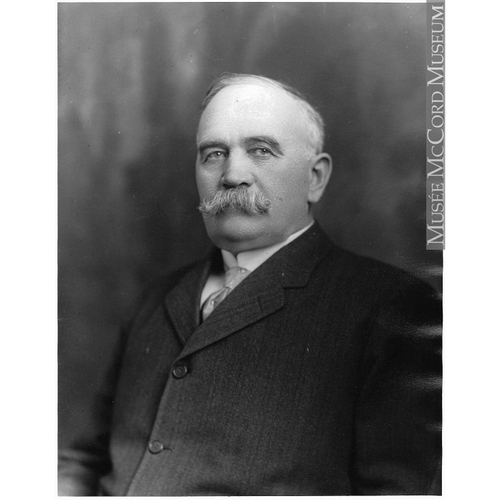

CURRY, NATHANIEL, labourer, businessman, politician, and philanthropist; b. 26 March 1851 in Terry’s Creek (Port Williams), N.S., one of the 11 children of Charles Curry, a farmer and vessel owner, and Eunice R. Davidson; m. 17 Sept. 1881 Mary E. Hall in Amherst, N.S., and they had five sons; d. 23 Oct. 1931 in Tidnish, N.S.

After receiving a basic education at schools in rural Kings County, Curry was apprenticed at age 15 to a local carpenter. About 1871 he joined the growing flood of youth moving from the Maritime provinces to New England in search of better economic prospects. He first settled in Boston, but he soon moved west to the frontier mining towns of Virginia City and Carson City, Nev. There he was employed by the Virginia and Truckee Railroad as an assistant foreman and millwright, where he picked up experience that would fundamentally shape his subsequent business career. In 1877 he returned to Nova Scotia, residing in Amherst, where he formed a partnership with his brother-in-law Nelson Admiral Rhodes*.

The two men apparently decided that Amherst, Rhodes’s birthplace, offered major opportunities now that confederation and the construction of the Intercolonial Railway were opening up Cumberland County to major economic expansion, especially in the coalmines of Springhill and nearby towns. Rhodes and Curry first formed a short-lived partnership with Bayard Dodge, a producer of sashes and doors. After Dodge’s departure, the two developed their enterprise, called Rhodes, Curry and Company, into a construction firm with projects in communities located on a network of railways that was expanding across the region. Working with architects such as Nova Scotian James Charles Philip Dumaresq*, the company would be responsible for the construction of thousands of buildings in the Maritimes, including the new main building and the ladies’ seminary building at Acadia College (1878), Halifax’s city hall (1890), and a house near Baddeck for Alexander Graham Bell* (1893). Backed by a consortium of local investors, buoyed by loans from Halifax investors, and having insider connections to the ruling Conservative Party (through Amherst native Sir Charles Tupper*), Rhodes, Curry had become a formidable presence in regional business by the 1890s. In 1891 the partners incorporated their company.

About 1880 Curry had started to repair railway cars, and later he built them. Rhodes appears to have been the dominant figure early in the partnership, but Curry’s ascendency became evident around 1893, after the firm had bought out the railway-car works formerly owned by James Stanley Harris* and moved the business from Saint John to Amherst. Rhodes concentrated on general contracting operations while Curry, drawing on knowledge he had gained in the American west, supervised railcar construction. By 1903 they controlled a sprawling industrial complex spread along the main line’s tracks in downtown Amherst. An integrated array of forges, milling shops, axle works, a rolling mill, and carpentry facilities generated an output of 4,000 freight and 60 passenger cars that year. With assets of $3 million, annual sales of $2.3 million, branches in New Glasgow, Sydney, and Halifax, and a workforce exceeding 1,500, Rhodes, Curry overshadowed all its competitors in the Canadian railcar market, selling not just locally, but also to out-of-region companies such as the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Correspondent with his rise as an entrepreneur, Curry assumed an increasingly prominent place in community affairs. He had championed Amherst’s incorporation in 1889 and subsequently served as mayor in 1894. He also became active in the masonic order and was a pillar of the local Baptist church, which his company built. His wife took a leading role in local charities, notably the Ladies Hospital Aid Society. Indicative of the family’s rising wealth and social status, their eldest son was sent to the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ont., and eventually achieved the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the Canadian militia. Early in the 20th century Curry built a three-storey wooden mansion in Tidnish, overlooking the Northumberland Strait. There, on an estate that eventually grew to 350 acres, the family spent their summers entertaining, overseeing the operation of a model farm and the landscaping of elaborate gardens, and sailing on their private yacht.

Technological innovation fascinated Curry. In 1904 he joined other Amherst notables in founding a firm that pioneered the generation of electricity at the pithead of a coalmine and transmitted it over high-tension wires, an innovation that reduced power costs for Amherst industrialists. In 1906 he spearheaded the establishment of the Malleable Iron Works in the town to facilitate a transition to the manufacture of all-steel railcars for Rhodes, Curry. Such modernization was becoming essential to remaining competitive, but it posed enormous challenges, particularly in raising the needed capital. In 1909 what had begun as a drive to turn the partnership into a widely owned joint-stock company took on a radically different character. Montreal-based William Maxwell Aitken*, a rising star in Canadian high finance who had been shepherding the restructuring of Rhodes, Curry, saw that he had an opportunity to merge the firm with two other railcar factories located in central Canada. The deal meant that Rhodes, Curry became just one component of a new corporate giant, the Canadian Car and Foundry Company Limited, headquartered in Montreal.

Although Curry had been initially hesitant about the loss of autonomy that a merger represented, by 1909 he was ready to cooperate. Rhodes had unexpectedly died earlier that year. Perhaps more persuasive factors were that Curry emerged with nearly $3 million of the $8.5 million capital stock of the new corporation and was further rewarded with the presidency of Canadian Car and Foundry, a post he would retain until 1919. His expanded responsibilities meant that he was obliged to move to Montreal, where he took a long-term lease on a suite of rooms at the Windsor Hotel, returning, however, to his Tidnish estate every summer. He quickly gained acceptance into the inner circle of central Canada’s business elite, ultimately becoming the president of a dozen corporations and serving as director of some 30 firms, including such giants as the Bank of Nova Scotia and the Montreal Trust Company. Even greater recognition came in 1911–12 when he was elected vice-president and then president of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association (CMA).

Curry became leader of the CMA just as Canada was plunged into the highly divisive election of 1911, fought largely over the issue of easing tariff barriers between Canada and the United States. Curry did not campaign beyond Nova Scotia, but he made it clear through the press and placards erected in his workshops that both he and the CMA wanted no deviation from the protectionist policies put into place 30 years earlier by the government of Sir John A. Macdonald*. His stance against reciprocity ensured that he had no trouble raising money for the Conservative Party. Headed by fellow Nova Scotian Robert Laird Borden, the Tories won, and in 1912 Curry was rewarded for his services in the form of appointment to the Canadian Senate as a representative of his home province. Earlier that May he had received an honorary lld from Acadia University. Dr Curry, as he liked to be addressed, would make the school the major beneficiary of the approximately $200,000 he eventually donated to various institutions of higher education.

Unfortunately, the transformation from an independent company into a part of a larger organization would not prove beneficial to Amherst and the workers whose livelihood had come to depend on the factory complex, which was also known as Canada Car. Although never subjected to the opportunistic and buccaneering leadership style found in the coal and steel industries of Cape Breton Island, the Amherst facility fell prey to the problem of being a branch plant operation located in a region characterized by relative economic underdevelopment.

On leaving for Montreal, Curry had told his employees that their future was secure and assured them that new investment would allow them to manufacture all-steel cars and perhaps diversify into the production of locomotives. He was probably sincere, but events conspired against his plans. When Canada Car finally modernized in 1912, it chose to build its new all-steel car facility in Thunder Bay, Ont., near the prairie west, where demand for rolling stock was greatest. This decision was followed by a sharp downturn in the Canadian economy in 1913, and the next year the Great War broke out in Europe, temporarily stifling new investment. Seeking compensation for the business lost to the new plant in Ontario, Curry used his political connections in Ottawa to secure munitions contracts [see Sir Joseph Wesley Flavelle] for the company’s eastern plants, including the one in Amherst. Although these contracts allowed the town’s facility to temporarily increase its workforce, the boost was not nearly enough to restore it to its former glory. The fact that many local Canada Car buildings were lent to the government rent-free during the war was emblematic of the ongoing decline of the company and of the local manufacturing economy. Once hostilities ended in 1918, the plant faced an uncertain future, with much of its equipment obsolete.

At this critical juncture labour militancy added further complications to the situation in Amherst. On 19 May 1919 workers at Canada Car, frustrated by years of relatively low wages, seasonal layoffs, and management’s persistent refusal to countenance collective bargaining, went on strike. Their walk-out led to a general work stoppage by most of Amherst’s industrial labourers, just days after the Winnipeg General Strike began [see Mike Sokolowiski*]. Their old master proved unsympathetic. Seeing himself as a model for others, in the Halifax Herald of 20 Sept. 1911 Curry boasted that “the employee of today may be the employer of tomorrow.” Oblivious to the ways in which industrial consolidation had undermined workers’ prospects, Curry insisted that labour unrest essentially derived from “Bolsheviki”-led conspiracies.

Even if he had been favourably disposed towards Amherst workers, Curry was no longer in control of policymaking at Canada Car. In 1919 he was elevated to the relatively titular position of chairman of the board. He was almost 70, his friend Sir Robert Borden retired in 1920, and Curry lost much of his corporate leverage. His waning influence was a factor in the decision to separate the construction operations of the former Rhodes, Curry company from Canada Car that year. By the middle of the decade the Amherst railway-car installation, still part of Canada Car, had been reduced to a ramshackle repair facility with a tiny workforce. Depopulation and debt stalked what had once been “busy Amherst,” as it had been known in the Maritimes; between 1921 and 1931, the town lost about a quarter of its population.

After World War I Curry’s personal life remained, at least superficially, enjoyable. Known to his friends as Nat, he acquired a winter home in Bermuda and travelled extensively, taking a world tour with his wife. A gregarious man with a lively passion for yachting, hunting, and fishing, Curry belonged to elite social clubs in Montreal (Mount Royal, Engineers’, Canadian), Ottawa (Rideau), Toronto (National, Albany), Halifax (Halifax), and Amherst (Marshlands). Yet tragedy haunted the family. In 1907 he and his wife had lost a son with a promising future to pneumonia. In 1915 a second son became a casualty of war. Local oral tradition suggests that late in life Curry had an uneasy relationship with his three surviving sons. Alcohol abuse seems to have been a major problem, particularly with Curry himself. In his last years he often needed private nursing care as he struggled to regain his health.

In 1931 Curry died of a heart attack. In his will he assigned all his wealth to his wife and set up trusts for their grandchildren. His capital could not be touched by his sons. Ironically, his efforts to dispose of his estate as he wished ultimately proved useless because his stock portfolio was wiped out in the early months of the Great Depression by unwise investment decisions. Little remained for the heirs other than a life-insurance policy and the estate at Tidnish.

Nathaniel Curry liked to think of himself as a self-made man. Reality was more complex. He gained fame and wealth largely because of the role played by Canada’s corporate-led restructuring in the early-20th-century economy. The process of shifting industrial investment from the Maritimes to central Canada, compounded by the onset of the Great Depression, brought ruin both to him and to the town where he had once been the leading captain of industry.

LAC, R233-37-6, N.S., dist. Cumberland (30), subdist. Amherst (A): 34. NSA, Cumberland County Court of Probate, file 2915 (Nathaniel Curry); Cumberland County registry of deeds, vol.36, file 531; vol.37, files 483–84; vol.46, files 222–23; MG 1, vol.800, nos.5, 9–11, 17 (S. L. Shannon papers). Halifax Herald, 17 Sept. 1894, 20 Sept. 1911, 23, 24 Oct. 1931. Biographical review … of leading citizens of the province of Nova Scotia, ed. Harry Piers (Boston, 1900). Can., Royal commission on the relations of capital and labor in Canada, Report: evidence – Nova Scotia (Ottawa, 1889), 310–13; Senate, Debates, 1913–14, 1919–23, 1925, 1930. C. E. Goad, “Insurance plan, town of Amherst” (n.p., [1914]; available at NSA). A. R. Lamy, “The development and decline of Amherst as an industrial centre: a study of economic conditions” (ba thesis, Mount Allison Univ., Sackville, N.B., 1930). G. P. Marchildon, Profits and politics: Beaverbrook and the Gilded Age of Canadian finance (Toronto, 1996). National cyclopædia of American biography … (63v., New York, [etc.], 1892–1984), 17. J. N. Reilly, “Emergence of class consciousness in industrial Nova Scotia: Amherst 1891–1925” (phd thesis, Dalhousie Univ., Halifax, 1983).

Cite This Article

David A. Sutherland, “CURRY, NATHANIEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/curry_nathaniel_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/curry_nathaniel_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | David A. Sutherland |

| Title of Article: | CURRY, NATHANIEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2019 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | December 17, 2025 |