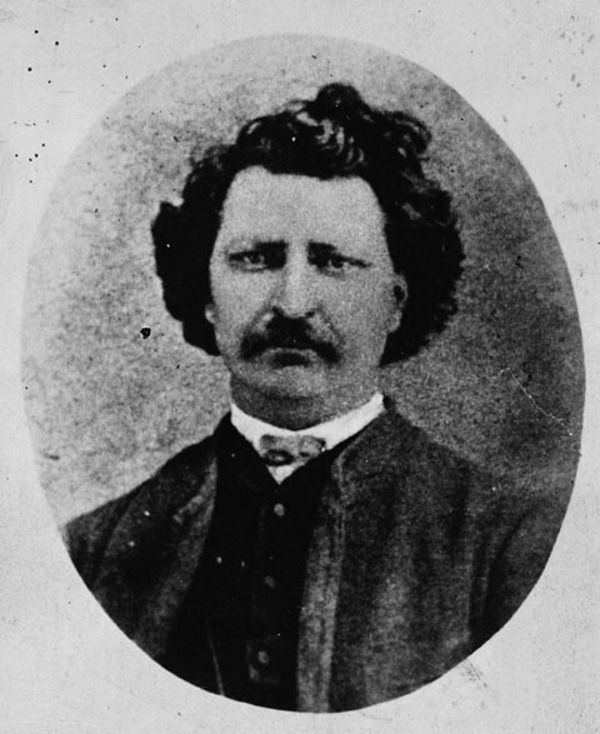

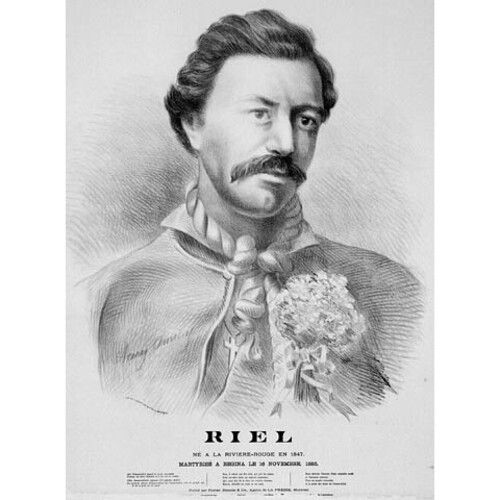

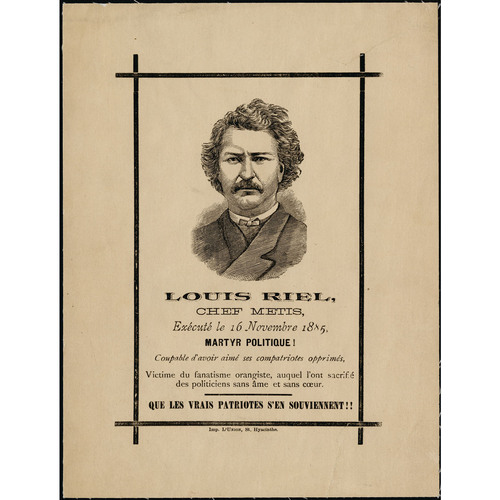

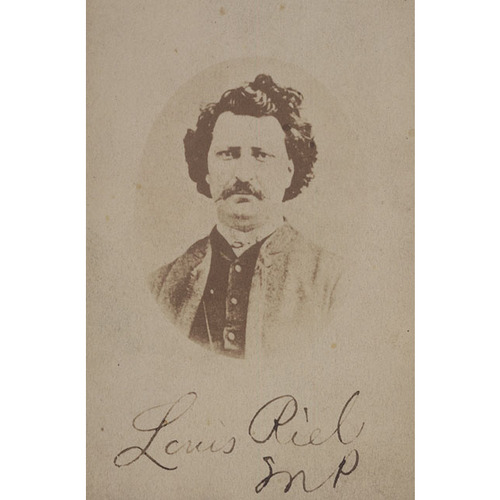

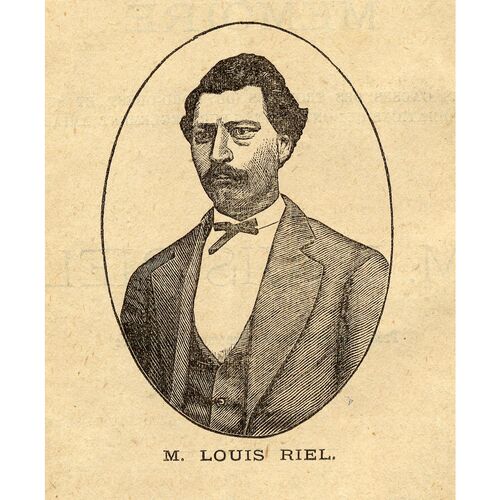

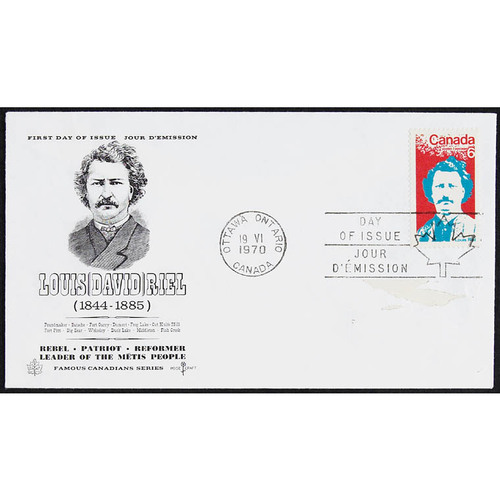

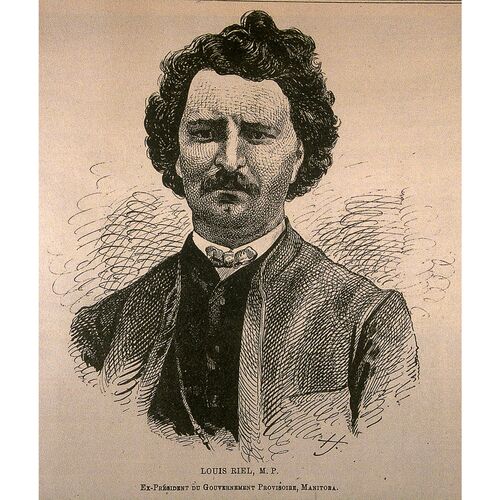

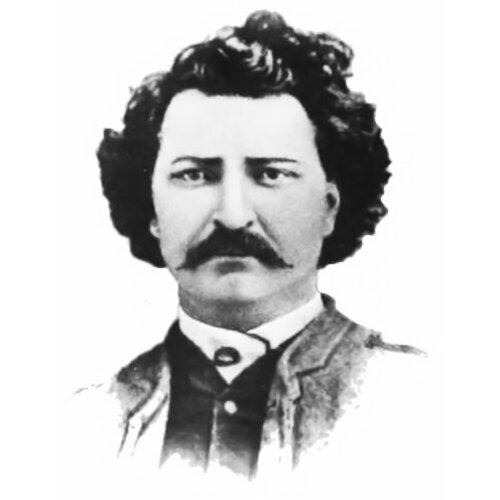

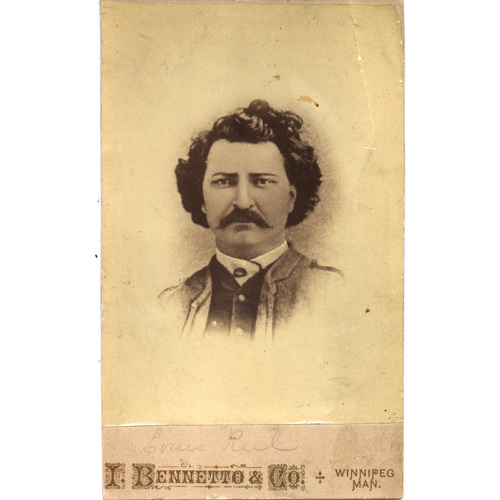

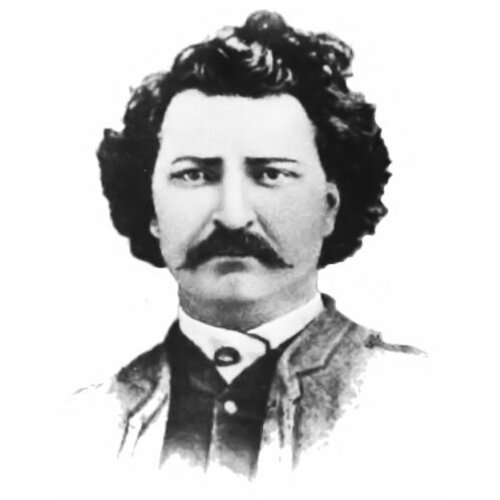

RIEL, LOUIS, Métis spokesman, regarded as the founder of Manitoba, teacher, and leader of the North-West rebellion; b. 22 Oct. 1844 in the Red River Settlement (Man.), eldest child of Louis Riel* and Julie Lagimonière, daughter of Jean-Baptiste Lagimonière* and Marie-Anne Gaboury*; m. in 1881 Marguerite Monet, dit Bellehumeur, and they had three children, the youngest of whom died while Riel was awaiting execution; d. 16 Nov. 1885 by hanging at Regina (Sask.).

Louis Riel is one of the most controversial figures in Canadian history. To the Métis he is a hero, an eloquent spokesman for their aspirations. In the Canadian west in 1885 the majority of the settlers regarded him as a villain; today he is seen there as the founder of those movements which have protested central Canadian political and economic power. French Canadians have always thought him a victim of Ontario religious and racial bigotry, and by no means deserving of the death penalty. Biographers and historians over the years since Riel’s death have been influenced by one or other of these attitudes. He remains a mysterious figure in death as in life.

Riel was the eldest of 11 children in a close-knit, devoutly religious, and affectionate family. Both his parents were westerners, and he is said to have had one-eighth Indian blood, his paternal grandmother being a Franco-Chipewyan Métisse. Louis Sr, an educated man, had obtained land on the Red River, where he gained a position of influence in the Métis community. In 1849 he organized the community to aid Pierre-Guillaume Sayer*, a Métis charged with violating the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trade monopoly. Sayer was released, an action which resulted in the end of that monopoly. As a child, young Louis would have heard much of his father’s exploits.

While he was being educated in the Catholic schools in St Boniface, Riel attracted the attention of Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché*. Anxious to have bright Métis boys trained for the priesthood, Taché arranged in 1858 for Riel and three others, including Louis Schmidt, to attend school in Canada. At the Petit Séminaire de Montréal Riel showed himself to be intelligent and studious, with a capacity for charming others, but he could also be moody, proud, and irritable.

The news of his father’s death, which reached him in February 1864, was a traumatic shock for Riel. Always an introvert, subject to moods of depression, he seems to have lost confidence in his qualifications for the priesthood and withdrew from the college in March of the following year without graduating. Hoping to support his family in Red River, whom Riel Sr had left impoverished and in debt, Louis became a clerk in the Montreal law firm of Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme*. But the subtleties of the law bored and annoyed Riel and he decided, in all likelihood in 1866, to return to Red River. He probably worked at odd jobs in Chicago and St Paul (Minn.) before arriving at St Boniface in July 1868.

The Red River that Riel had left ten years earlier was an isolated society of English-speaking mixed-bloods (the country-born), Scottish settlers, and the French-speaking, Roman Catholic Métis. During the early 19th century the Métis, the largest group, had developed a vigorous sense of nationality based on a distinctive culture which combined Indian and French Canadian elements. For the most part, the Métis were indifferent to farming, preferring the excitement of the buffalo hunt far out on the western plains. These annual hunts were superbly organized and disciplined affairs under the control of democratically elected leaders, and Métis adherence to the hunt was dramatically reflected in their quasi-military social organization. In contrast to the Métis, the country-born were predominantly Anglican, proud of their English culture, and settled on the land. The Scots settlers had adhered strictly to the Presbyterian church.

Riel found many changes on his return. Religious antipathies had become a notable feature of the settlement. At the same time the political climate was both uncertain and volatile. The settlement, part of the Rupert’s Land held by the HBC, was still administered by a governor and the Council of Assiniboia, established by the HBC. The need for a new constitutional arrangement was acknowledged, but the issue was far from settled. Moreover, the old inhabitants now recognized that although their settlement was still isolated, it was the object of expansionist aspirations on the part of both the United States and Canada. Indeed, during Riel’s absence the settlement had grown to almost 12,000 and the village of Winnipeg had emerged, largely populated by Canadians and a handful of Americans. In fact, what Riel found at Red River in July 1868 was an Anglo-Protestant Ontario community, hostile to Roman Catholicism and the social and economic values of the Métis.

The most influential and vociferous personality among the Canadians was Dr John Christian Schultz*, an Ontario-born physician, trader, and land speculator. For Schultz and his followers the future of the settlement was obvious – annexation to Canada. In the early 1850s the annexation of the northwest had become a popular political issue in Canada West as a consequence of the activities of George Brown* and William McDougall*, the leaders of the Clear Grits. In French Canada, land seekers had been encouraged to look north in their own province, but their political leaders, by entering the confederation coalition of 1864, had tacitly accepted the idea of acquiring the northwest. This bipartisan understanding was embodied in section 146 of the British North America Act of 1867, which provided for transcontinental expansion. Shortly after Riel’s return to the west, it became known that Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald*, fearing the Minnesota annexationists, was again negotiating with the HBC for the transfer of Rupert’s Land, ignoring the population at Red River and the Council of Assiniboia.

Meanwhile, a grasshopper plague in 1867–68 had caused much distress in the settlement. The Canadian government had proposed providing relief by financing the building of a road from Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) to Lake of the Woods; because the government anticipated that the country would soon be annexed it felt the road, named “the Dawson Road” after engineer Simon James Dawson*, would be essential. But the project was poorly administered, and the survey party assembled in the settlement by John Allan Snow, head of the project, and Charles Mair*, its paymaster, who arrived together from Ontario in October 1868, included no French-speaking members. Mair, a poet and friend of McDougall, now the minister of public works, made himself thoroughly unpopular in the settlement by a series of articles in Ontario newspapers in January 1869 criticizing the Métis. He was opposed to the expedient biculturalism of the Red River Settlement, and, being an advocate of large-scale Ontario immigration to the northwest, was a natural ally of Dr Schultz, the road party’s agent. Thomas Scott*, an Irishman and fervent Orangeman who was reckless, stubborn, and contemptuous of the Métis, joined the work crew in the summer of 1869.

At St Vital, an idle Riel had initially decided “to wait on events, quite determined just the same to take part in public affairs when the time should come.” When the substance of Mair’s articles became known to the settlement, Riel defended the Métis against this unjust criticism in a strong reply published in Le Nouveau Monde (Montreal) in February 1869. He attended and spoke at a meeting called on 19 July by well-established leaders of the Métis community, such as Pascal Breland* and William Dease, to discuss growing Métis fears about the course of events. Though the meeting underlined the need for concerted action, none was planned.

In July 1869 Métis suspicions had increased when McDougall ordered a survey of the settlement. The head of the survey party, Colonel John Stoughton Dennis, was given specific instructions to respect the river lots of the settlers. Nevertheless, he received a cool reception in Upper Fort Garry and St Boniface after he arrived on 20 August, and his close association with Dr Schultz increased Métis fears. William Mactavish*, the governor of Assiniboia and of Rupert’s Land, believed that “as soon as the survey commences the Half breeds and Indians will at once come forward and assert their right to the land and possibly stop the work till their claim is satisfied.” He considered the survey premature and unwise, and he cautioned the Canadian government. Robert Machray*, the Anglican bishop of Rupert’s Land, and Bishop Taché, who called at Ottawa on his way to Rome, also warned the government. But all representations were ignored by Macdonald. Indeed, in late September matters worsened when it was announced that McDougall, who with Sir George-Étienne Cartier* had concluded negotiations between the HBC and Canada in London, would be the first lieutenant governor of the territories. No poorer choice for the post could have been made, in view of the necessity for diplomatic caution in dealing with the officials of the HBC and with the lay and clerical spokesmen of the various groups at Red River. The transfer was to take place on 1 Dec. 1869.

As tensions mounted among the Métis it was clear that strong leadership was needed. Riel’s experiences during the past ten years had produced a life-style very different from that of the buffalo-hunting Métis, but it was these people he now aspired to lead. The older, more established leaders had had little success and had shown little initiative. Riel – ambitious, well-educated, bilingual, young and energetic, eloquent, deeply religious, and the bearer of a famous name – was more than willing to provide what the times required.

Late in August 1869, from the steps of the St Boniface cathedral, Riel declared the survey a menace. On 11 October a group of Métis, including Riel, stopped the survey. A week later, the National Committee, with John Bruce as president and Riel as secretary, was formed in St Norbert with the support of the local priest, Noël-Joseph Ritchot*. This association of the clergy and the Métis is not surprising: a people surrounded or threatened by an alien culture frequently find in their church the chief sustainer of their traditions and aspirations. The able Bishop Taché had already put into print his understanding of and sympathy for the Métis as an integral, and now threatened, part of the settlement.

On 25 October Riel was summoned to appear before the Council of Assiniboia to explain his actions. He declared that the National Committee would prevent the entry of McDougall or any other governor unless the union with Canada was based on negotiations with the Métis and with the population in general. However, by 30 October McDougall had reached the border at the village of Pembina (N. Dak.) and, despite a written order from Riel, he proceeded to the HBC Pembina post (West Lynne, Man.). Here on 2 November McDougall was met by an armed Métis patrol, commanded by Ambroise-Dydime Lépine*, and ordered to return the next day to the United States. Also on the 2nd, Riel, with followers reported as numbering up to 400, who had been recruited from the fur-brigades recently returned to the settlement for the season, took possession of Upper Fort Garry without a struggle. It was a brilliant move on Riel’s part – control of the fort symbolized control of all access to the settlement and the northwest.

The month of November 1869 was one of intense activity in the Red River Settlement as Riel worked to unite its residents, including established Métis such as Charles Nolin* and William Dease, who initially opposed him. On 6 November Riel issued an invitation to the English-speaking inhabitants to elect 12 representatives from their parishes to attend a convention with the Métis representatives. Somewhat reluctantly the country-born and the Selkirk settlers [see Thomas Douglas*] agreed with the proposal. At the first meeting of the convention little was accomplished and the English-speaking delegates, led by James Ross*, criticized the exclusion of McDougall from the settlement as smacking of rebellion. Riel angrily denied this allegation. Responding to another charge, he stated that he had no intention of invoking American intervention; throughout the resistance he insisted that the Métis were loyal subjects of the queen.

On 16 November Mactavish, as governor at Red River, issued a proclamation requiring the Métis to lay down their arms. In response Riel proposed a further step to the convention on 23 November: the formation of a provisional government to replace the Council of Assiniboia and to negotiate terms of union with Canada. He did not succeed in rallying the English-speaking parishes behind this move. Nor did they approve the “List of Rights” which Riel presented to the convention on 1 December after McDougall issued a proclamation stating that the northwest was part of Canada as of that day and that he was its lieutenant governor. The “List,” probably composed by Riel, consisted of 14 items. It proposed representation in the Canadian parliament, guarantees of bilingualism in the legislature, a bilingual chief justice, and arrangements for free homesteads and Indian treaties. When the “List” was later printed and widely distributed many of the English-speaking population were converted to the view that the Métis demands were not unreasonable.

More serious opposition was mounted by Schultz, Dennis, and the Canadian element of the settlement. McDougall had requested Dennis to recruit a force to arrest the Métis occupying Upper Fort Garry, a threat Riel took seriously, but most of the English-speaking settlers refused to respond to Dennis’ call to arms and he retired to Lower Fort Garry. Schultz, on the other hand, had fortified his house and store, and recruited about 50 followers as guards. He proposed to Dennis that he be allowed to attack Upper Fort Garry and capture Riel. Before this could happen Riel’s soldiers surrounded Schultz’s store and demanded his surrender. Realizing their position was hopeless, on 7 December the Canadians gave in and were imprisoned at Upper Fort Garry. The next day Riel established the provisional government, and Bruce was named president. On 18 December McDougall and Dennis left Pembina for Ontario, having been informed that the Canadian government had in fact postponed union until the British government or the HBC could guarantee a peaceable transfer.

Macdonald later admitted that under the circumstances the people of the community had had to form a government for the protection of life and property. Yet, in an alcoholic haze or because of urgent political problems in Canada, he did not, in fact, fully realize at the time the state of affairs in the settlement, and Canadians generally seemed unconcerned. On 6 December, nevertheless, Macdonald had sponsored a proclamation by the governor general of an amnesty to all in Red River who would lay down their arms. He also appointed a two-man goodwill mission consisting of Abbé Jean-Baptiste Thibault*, a priest who had been a missionary in the northwest for more than 35 years, and Colonel Charles-René-Léonidas d’Irumberry de Salaberry. Thibault arrived in the settlement on Christmas Day, while Salaberry remained in Pembina.

On 27 December, at the settlement, Riel took over from Bruce as president of the provisional government, and on the same day Donald Alexander Smith*, appointed by Macdonald’s government as a special commissioner, arrived quietly with his brother-in-law Richard Charles Hardisty, ostensibly on HBC business. When Salaberry in his turn reached the settlement on 5 Jan. 1870 he and Thibault met with Riel and the Métis council. It was apparent then that they had no authority to negotiate terms of union; moreover, Thibault’s discussions with the priests of the settlement converted him to the Métis viewpoint. Smith, a more formidable influence than the other two commissioners, had been charged by Macdonald to offer money or employment to any of the leaders in the settlement amenable to cooperation, and to present the Canadian government’s plans. By distributing the government’s money carefully he was able to attract several leading Métis but, after meeting with Riel on 6 January, he concluded that “no good could arise from entering into any negotiations with his Council.” Smith decided to present his instructions at a public meeting. He had, however, left his official commission in Pembina to avoid its seizure by Riel, who asked to see it. Now Smith was able, with the assistance of some of the Métis who were supporting him, to out-manœuvre the president and have Hardisty deliver the commission to him at Red River, where he was under house arrest. Riel had to accede to Smith’s desire for a mass meeting.

On 19 Jan. 1870 a large crowd assembled in the square at Fort Garry and, with Thomas Bunn* in the chair and Riel acting as interpreter, Smith made his case. Although it differed little from that of Thibault and Salaberry, it was received calmly. Smith promised a liberal policy in confirming land titles to present occupants and representation on the proposed territorial council. The meeting was continued on the following day with an even larger crowd. The atmosphere of this session had changed and the listeners were now firmly behind Riel. Growing more confident and reaching the height of his influence, he realized that the meeting wanted something more than assurances of goodwill, and, taking the initiative, he proposed that a convention of 40 representatives, equally divided between the two language groups, meet the following week to consider Smith’s instructions in detail. The proposal was approved. When the convention met on 26 January Riel was conciliatory, nominating Judge John Black* as chairman and agreeing that a new “List of Rights” should be prepared by a committee of six, three from each language group. A new, slightly modified “List” was presented on the 29th and the convention proceeded to debate it until 3 February when the last clause, no. 19, was accepted. Riel then proposed that the convention demand the immediate grant of provincial status, presumably for the whole northwest. This would have meant control of crown lands and other natural resources, but the proposal was rejected, some considering it premature. He failed again on the 5th when he proposed that the convention repudiate the agreement between Canada and the HBC and that the negotiations be between Canada and the settlement.

On 7 February the convention discussed the new “List of Rights,” first with Thibault and Salaberry, and then with Smith, though Riel still contended that Smith could not provide any specific guarantees. Smith thereupon declared that he had been authorized to propose the sending of a delegation to Ottawa which would be given “a very cordial reception.” The proposal, which would entail direct negotiations between Canada and the settlement, was what Riel had planned and advocated from the beginning of the resistance, and it was accepted with enthusiasm. Riel then suggested that since a government was needed until the parliament of Canada provided a constitution, both language groups should participate in the provisional government. The English-speaking representatives at the convention hesitated until a delegation sent on the 9th to consult with Governor Mactavish reported that although he refused to delegate his authority he agreed with the proposal. The country-born and the Scottish delegates were now satisfied that they should cooperate further with Riel.

The committee which had drafted the “List of Rights” in January was asked to submit a constitution for the provisional government. The committee’s proposals, which were accepted on 10 February, established an assembly of 24 elected representatives drawn equally from the French-speaking and English-speaking parishes of the settlement. The General Quarterly Court of Assiniboia would continue to administer the law. Recognizing Riel’s strong position, the committee also recommended that he be president. He then selected an executive of Thomas Bunn (secretary), William Bernard O’Donoghue* (treasurer), and James Ross (chief justice), and nominated a three-man delegation to proceed to Ottawa when required – Abbé Ritchot representing the Métis, Judge Black representing the English-speaking settlers, and Alfred Henry Scott* representing the Americans although he may have been a British subject. Riel had reached the pinnacle of his hopes and ambitions, and he could afford a gesture of generosity – he promised to release all the prisoners held at Upper Fort Garry.

It now appeared that a united front had been achieved in the settlement. The pro-American element, which in the persons of Enos Stutsman* and Oscar Malmros was intriguing in favour of annexation to the United States and promoting it through the New Nation begun in Winnipeg on 7 January, was seeing its limited influence on events diminishing. On the other hand the unscrupulous triumvirate of Schultz, Mair, and Thomas Scott was determined to foment civil war to eliminate Métis power. However, as outsiders they misjudged the willingness of the country-born and Scottish settlers to oppose the Métis. Unfortunately for all concerned the three men had escaped from Upper Fort Garry in January 1870. Schultz had made his way downstream to drum up support for an armed force in the English-speaking parishes and among the Indians. Mair and Scott had gone to Portage la Prairie, a Canadian settlement, where, to gain support, Scott retailed horror stories of his imprisonment. At Portage, Charles Arkoll Boulton*, captain of the 46th militia regiment and a member of Dennis’ survey crew, was inveigled into assuming the leadership of a force which left Portage on 12 February with the objective of joining Schultz’s party at Kildonan (now part of Winnipeg). The ostensible reason for action was to free the Canadian prisoners in Fort Garry. The last of them was released on 15 February, but this had no effect on Schultz, Mair, and Scott, and their real purpose – to overthrow the provisional government – was revealed. The Portage party, including Boulton, decided to return home but, contrary to Boulton’s advice, marched as a body close to Fort Garry instead of dispersing to make their way west. News of the expedition had caused intense excitement in Fort Garry and every available man was called in to defend the fort. When the armed Portage party approached the fort on 17 February, a small force of some 50 men arrested the 48 Canadians, including Scott and Boulton, and took them to the recently vacated cells in Fort Garry. Schultz, realizing that he was a marked man, left for Ontario.

Riel correctly believed that it was the Canadians who were responsible for the turbulence in the settlement; they had twice resorted to force to overthrow him. One of them needed to be punished, and Boulton was condemned to death, a more severe sentence than any inflicted by a Métis leader on a disruptive member of a buffalo hunt. A number of people appealed for clemency, among them Donald Smith, but Riel only relented when he obtained from Smith a promise to persuade the English parishes to elect representatives. Thomas Scott, regarding the pardon as a sign of weakness, proceeded to insult his Métis guards, who became so angry that they would have given him a severe beating had Riel not intervened. He warned Scott to behave. An ignorant and bigoted young man with a profound contempt for all mixed-bloods, Scott thought that the Métis were cowards. When he continued to make difficulties the guards insisted that he be tried by court martial and he was charged with insubordination; Scott was sentenced to death by a jury which was presided over by Ambroise-Dydime Lépine and which included Jean-Baptiste Lépine*, André Nault*, and Elzéar Goulet*. On this occasion the appeals of Smith and others were firmly rejected by Riel. Whether he was worried by the signs of insubordination among his followers, whether he persuaded himself that the settlement was in danger, or whether he thought it necessary to intimidate the Canadian conspirators and show Canada that the Métis and their government would have to be taken seriously, will always be debated. Professor G. F. G. Stanley believes the last consideration, Riel’s own explanation, to be true. In the settlement the death of Scott on 4 March was soon forgotten but in Ontario the “murder” became a major issue. As people then and later have said, it was Riel’s one great political blunder.

Bishop Taché arrived back in the settlement on 8 March 1870. He had been summoned from Rome, and as soon as he docked at Portland, Maine, in early February, he had a request from Cartier to come to Ottawa for discussions. Taché received a copy of the December proclamation of amnesty, which he was given to believe covered every action that had taken place or might take place before his return to the settlement, including any acts of violence. When he reached Red River he extended this assurance categorically to Riel and Ambroise-Dydime Lépine. On 15 March Taché met with the newly elected council and read a telegram from the secretary of state for the provinces, Joseph Howe*, which stated that the “List of Rights” was “in the main satisfactory” and that delegates should come to Ottawa to work out an agreement. Taché then requested that the prisoners be released. Riel agreed, and the jails were again emptied.

On 22 March Ritchot, Black, and A. H. Scott received yet another “List of Rights,” this one prepared by the executive of the provisional government, which included the following provisions: that a province be established, not liable for any portion of the public debt of the dominion; that during a term of five years it not be subject to any direct taxation except for municipal purposes; that a sum equal to 80 cents per head be paid annually to the province by the Canadian government; that it have control of the public lands; that treaties with Indians accord with the wishes of the province; that uninterrupted steam communication from Upper Fort Garry to Lake Superior be provided and that all public buildings, bridges, roads, and other public works be paid for by the federal government; that the English and French languages be used in the provincial legislature and courts and in all public documents and acts; that the lieutenant governor and the judge of the superior court should be familiar with both the English and the French languages; that an amnesty be extended to all members of the provisional government and its servants; and that no further customs duties be imposed until there was uninterrupted railway communication between Winnipeg and St Paul. Before the delegates left, a fourth “List” was drawn up, doubtless with Riel’s and Taché’s blessing. This added a provision for separate schools according to the system existing in the province of Quebec, and outlined the structure for a provincial government. On 23 and 24 March 1870 the delegates set out for Ottawa.

When Schultz and Mair arrived in Toronto in early April they were secretly brought in touch with George Taylor Denison* III and other members of what became the Canada First group [see William Alexander Foster]. Ontarians had been up to now rather indifferent to the events in Red River, but news of Scott’s execution made it possible to whip up a frenzy of hatred against Riel and the delegates. The Denison–Schultz activists secured the editorial support of most of the Toronto newspapers. They also planned meetings to be addressed by Schultz and Mair throughout the province. The appeal was anti-French, anti-Catholic, and to some extent anti-Macdonald for receiving a delegation representing the “murderers” of the “heroic” Thomas Scott. It was also arranged in Toronto that Ritchot and A. H. Scott would be arrested on a charge of abetting murder. They were indeed arrested soon after their arrival in Ottawa on 11 April, but were released because the judge decided that the Toronto warrant was not legal. They were then immediately re-arrested on a new warrant sworn in Ottawa. When the case was heard nine days later the crown prosecutor declined to proceed, and the delegates were finally free to pursue their mission.

On 22 April the delegates wrote to Howe requesting the opening of negotiations. Four days later Howe replied with a formal invitation to begin talks with Macdonald and Cartier. Ritchot was the real spokesman of the delegation, Black being inclined to compromise on the “List of Rights” and Scott being a silent supporter of Ritchot. Cartier and Macdonald rapidly discovered that the priest was a formidable negotiator, and that he was determined to extract concessions that would guarantee protection for the original inhabitants of Red River against the anticipated influx of Ontario land seekers and speculators. The results of the bargaining, embodied in the Manitoba Act of 1870, were a substantial achievement for Ritchot. Provincial status was granted to Manitoba (the name favoured by Riel), although Macdonald and Cartier succeeded in limiting the size of the province to about 1,000 square miles and not the entire northwest. Provincial control of natural resources, including all lands, was denied, but after hard bargaining 1,400,000 acres in the northwest were set aside for the Métis as a compromise. Bilingualism was recognized in the proceedings of the courts, the legislature, and in government publications. Historians have argued over whether the act was a genuine commitment to the extension of bilingualism to the west or, as some have suggested, merely a surrender to Riel’s alleged dictatorship. A critical examination of the four lists of rights, which were the basis of the negotiations and the act, supports the former view. On one important point, however, Ritchot failed dismally – an updating of the amnesty of 6 December. Because of the political pressure of Ontario, being whipped up by Schultz and his associates, all that Ritchot could obtain was an oral assurance from Governor General Sir John Young* and Cartier that the British government was being asked to intervene. Ritchot noted in his journal: “His Excellency assured me that . . . Her Majesty was going to proclaim a general amnesty immediately, that we [the delegates] could set out for Manitoba, that the amnesty would arrive before us.”

Somewhat isolated from the events in Ottawa, Riel had given his attention to the affairs of the settlement. As president of the provisional government, he had remained in Upper Fort Garry, though he returned control of the fort to the HBC to allow the resumption of trade. Perhaps more important, he worked assiduously to maintain the sometimes uneasy peace of the settlement. Nathaniel Pitt Langford, an American who visited it as an agent for the Northern Pacific, met Riel at this time and wrote: “Riel is about 28 years of age, has a fine physique, of active temperament, a great worker, and I think is able to endure a great deal. He is a large man . . . of very winning persuasive manners; and in his whole bearing, energy and ready decision are prominent characteristics; – and in this fact, lies his great powers – for I should not give him credit for great profundity, yet he is sagacious, and I think thoroughly patriotic and no less thoroughly incorruptible.”

Ritchot arrived back in Red River on 17 June 1870 and met immediately with Riel, who expressed satisfaction with the priest’s account of events. A week later, when the assembly met in Upper Fort Garry, Ritchot outlined the reception given to the delegation in Ottawa, which he described as generally friendly. On the question of amnesty he forecast that since the Canadian government was unable or unwilling to issue it before union, it would be forthcoming from the queen. The assembly thereupon, on 24 June, unanimously approved the terms of the Manitoba Act. To Riel the prospects seemed bright. But Bishop Taché was worried because Ritchot had not brought back a written guarantee of amnesty. Fearing that he was vulnerable to charges of misrepresentation, Taché returned to Ottawa to see Cartier, but he received only the same sort of assurances as those given Ritchot.

A new concern had appeared in May 1870 when a military expedition had been dispatched to Red River under Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley* on an “errand of peace.” The Canadian government had been considering such an expedition for some months, but Ontario’s demand for action had much to do with its realization. Indeed, although Wolseley was a British officer, and the expedition had imperial troops as well as militia units, the latter were dominated by young Ontario Orangemen thirsting for Métis blood, Riel’s in particular.

Throughout the negotiations, and in the early summer, Riel had grown uneasy about a deterioration of his support. Some Métis, mostly established farmers and traders, had never actually accepted his leadership and regarded him as an upstart. Another group, Professor William Lewis Morton* notes, “alternately supported and opposed him.” This was a St Boniface élite whose members are to be distinguished from the hunters and unemployed tripmen among whom Riel drew his strongest support. At the same time, Riel was concerned about the weakening of the always fragile relations between the Métis and the English-speaking elements in the settlement. But perhaps most important, he was worried by reports of the attitude of the Ontario volunteers in the approaching Wolseley expedition. William Bernard O’Donoghue had been sowing seeds of mistrust of all Canadian politicians and seemed to be gaining influence, even though Taché on his arrival in St Boniface on 23 August assured Métis leaders that “there was not the slightest danger.” But on the same day news arrived that the troops were nearing Red River; a governor had still not arrived to establish civil government, nor had word of the promised amnesty.

On 24 August Riel learned that the soldiers were planning to lynch him; he vacated Upper Fort Garry a few hours ahead of them. Accompanied by O’Donoghue and a few others, Riel crossed the Red River to Taché’s palace in St Boniface. He told the bishop he had been deceived, but added: “No matter what happens now, the rights of the métis are assured by the Manitoba Bill; it is what I wanted – My mission is finished.” Riel then proceeded to his home in nearby St Vital, where his mother lived; but growing more apprehensive about his safety he took refuge at St Joseph’s mission, about ten miles south of the border in Dakota Territory.

The new lieutenant governor, named on 15 July 1870, was Adams George Archibald*, a father of confederation from Nova Scotia and a member of parliament. He arrived in the settlement on 2 September and was at once confronted with the problem of maintaining order. Winnipeg was a place of riotous turbulence. Two Métis were among those killed [see Elzéar Goulet] and sympathizers with the resistance were threatened or assaulted by the Ontario militia volunteers who seemed bent on nothing short of assassinating all the Métis. Faced with this difficult situation Archibald went about the business of establishing a civil administration. Fluent in French, he formed a first provincial cabinet which was strictly bi-racial in character and had no members from the Canadian party. Alfred Boyd* became provincial secretary and Marc-Amable Girard* provincial treasurer.

Riel was pleased with the results of the first provincial election, held in December 1870, in which a majority of the elected members seemed well disposed towards him. He must have been particularly pleased that Donald Smith defeated Schultz in Winnipeg, though Schultz was subsequently elected to the House of Commons, along with Smith and a Métis, Pierre Delorme*. In February 1871, however, Riel became seriously ill, mentally overburdened with concern about his personal safety and with finding financial support for his family. It was not until May 1871 that he was strong enough to return home to St Vital.

Riel’s old associate, O’Donoghue, had by this time rejected his former chief; the parting of ways had occurred on 17 Sept. 1870 when, at a meeting at St Norbert which Riel attended, the latter had opposed O’Donoghue’s pleas to ask for the intervention of the United States in favour of the Métis. By October 1871 he had become the leader of a band of Fenians based across the international boundary. Having secured the support of John O’Neill* of Ridgeway fame, and counting on general support among the Métis, O’Donoghue planned to invade Manitoba. On 5 October he and some 35 followers crossed the border and captured the small HBC trading post of Pembina. But the Métis did not join them. Indeed, two Métis took O’Donoghue prisoner and turned him over to the American authorities. The invasion had lasted one day. However, the many rumours in Winnipeg concerning the seriousness of the Fenian threat had caused Archibald to issue a proclamation on the 4th calling on all loyal men “to rally round the flag.” Several companies of armed horsemen were recruited, one of them under the command of Riel. Archibald went to St Boniface to review the volunteers, was given a cordial reception, and shook hands with their leaders, including Riel. Archibald’s gesture was what Riel’s lay and clerical friends had hoped for, because it implied that he would no longer be an object of persecution. There were few in the province who thought of hanging Riel.

But when news of Archibald’s action reached Ontario there was an outburst of indignation. Mair was outraged and Denison led a campaign for his recall. Though both houses of the Manitoba legislature had enthusiastically endorsed Archibald’s action, Riel became a political issue in Ontario. Premier Edward Blake*, in 1872, went as far as to offer a $5,000 reward to anyone who would bring about the arrest of Scott’s “murderers.” For Macdonald it was essential to avoid a Quebec-Ontario confrontation over the Riel question, or any other question, before the 1872 general election. Tension would subside, he believed, if Riel could be induced to stay out of Canada for a time. Taché was to be the agent of this manœuvre. Macdonald gave him $1,000 and when Taché returned to the northwest he persuaded Smith to add £600 to an expense fund for Riel’s needs and the support of his family. Although he was bitter over his treatment, Riel accepted voluntary exile. He and Ambroise-Dydime Lépine made their way to St Paul, where they arrived on 2 March 1872. From St Paul Riel carried on an extensive correspondence with his friends in the settlement, particularly with Joseph Dubuc*, who had moved to St Boniface from Quebec in 1870 at the urging of Riel, Ritchot, Taché, and Cartier. But Riel felt increasingly insecure in St Paul, a centre swarming with Ontarians en route to Manitoba who could easily be induced by Schultz and the Ontario government’s reward to effect his arrest. Believing he would be safer among his friends, Riel returned to Red River in late June.

Dubuc and others now urged Riel to be a candidate for the riding of Provencher in the September 1872 federal general election. He agreed, despite warnings that he would be murdered if he set foot in Ottawa. But there was a new turn of events: Cartier was defeated in Montreal East early in September and Macdonald turned to Manitoba to find a seat for his Quebec lieutenant. Riel agreed to withdraw his candidature, as did his opponent Henry Joseph Clarke, in favour of Cartier, on condition that a settlement be reached on the guarantees made to the Métis regarding land. The question of amnesty he was prepared to leave to Cartier, whose sympathy on this point was a matter of record. On 14 September Cartier was elected by acclamation, but a mob of Canadians wrecked the offices of the two pro-Riel newspapers, the Weekly Manitoban (Winnipeg) and Le Métis (St Boniface). Even Smith was attacked by the Winnipeg rowdies.

For the next few months Riel was inactive. In Ottawa a renewed effort was made to secure the promised amnesty, but Macdonald was adamant; his political position was too weak after the election. The kaleidoscope of politics changed once again when Cartier died on 20 May 1873 in London. The champion of French rights in Manitoba, and the chief proponent in cabinet of an amnesty for Riel, was gone.

The death of Cartier meant a by-election would have to be held in Provencher, and Riel agreed to let his name stand, even though some of his friends predicted that he would never be allowed to take his seat and might well be killed; in fact, a warrant was issued at Winnipeg in September for Riel’s arrest, as well as that of Ambroise-Dydime Lépine, for the “murder” of Scott. Lépine was arrested at St Vital, but Riel escaped after being warned by Andrew Graham Ballenden Bannatyne. Riel was determined to plead his own case in parliament, where he knew he would have strong support among the French Canadian members. In the October by-election he was unopposed. Accompanied by Joseph Tassé*, Riel made his way to Montreal where Honoré Mercier* and two other friends conveyed him to Hull. At the last moment, however, Riel lost his courage and did not enter Ottawa, probably because he feared assassination or arrest on the murder charge. He returned to Montreal and in due course made his way to Plattsburg, N.Y., where he stayed with Oblate fathers. Here he was near Keeseville, a French Canadian lumber town, and, tired and depressed, he was often warmly received by the parish priest, Fabien Martin, dit Barnabé.

In November 1873 the Macdonald government resigned because of the Pacific Scandal; Alexander Mackenzie* became Liberal prime minister and called a general election for February 1874. In this election, which the Liberals won, Riel easily defeated Joseph Hamelin, the Liberal candidate in Provencher and a Métis who had not participated in the movement of 1869–70. Dubuc and Ritchot had campaigned actively on Riel’s behalf. He travelled to Ottawa where he signed the oaths’ book, but he was soon expelled from the house on the motion of Mackenzie Bowell*, seconded by Schultz. In September 1874, with the encouragement and support of Alphonse Desjardins*, Emmanuel-Persillier Lachapelle*, and the ultramontane Conservatives in Quebec, Riel was re-elected in the by-election in Provencher. He now saw his election as not only a victory for the Métis cause but also for the assertion of French and Catholic rights in Manitoba and the North-West Territories. However, he did not take his seat. Instead, he settled with Abbé Martin, Keeseville being close enough to Montreal to permit easy return to Canada. Here he learned that he had been expelled from the house for a second time.

On 13 October, in Winnipeg, Lépine’s trial got under way after a year of delay, with Joseph Royal* and the prominent Quebec Conservative, Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*, as defence counsel. In the first week of November Lépine was found guilty of Scott’s murder and sentenced to death by Chief Justice Edmund Burke Wood, despite the jury’s recommendation for mercy. Quebec was outraged at the outcome of the trial and the newspapers demanded amnesty for Lépine and Riel. What saved Lépine and assisted Mackenzie in his dilemma, for he could not accede to Quebec without offending Ontario, was the intervention of the governor general, Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*]; on his own authority Dufferin in January 1875 commuted the death sentence to two years’ imprisonment and the permanent forfeiture of political rights. Mackenzie, emboldened by the governor general’s move, secured parliamentary approval in February of an amnesty for Riel and Lépine, conditional on their banishment for five years. As a member in the Ontario Legislative Assembly Mackenzie had been strongly anti-Riel. As a prime minister of Canada, however, he was forced to equivocate and compromise until Dufferin had provided a way out of the impasse. Ironically, perhaps, Mackenzie’s actions resolved the prickly amnesty question.

Riel, exiled and with little apparent future, became more preoccupied with religious than political matters. During the strain of the previous five years he had suffered from bouts of nervous exhaustion, but now his mental and physical behaviour often revealed an obsession with the idea of a “mission”: he saw himself at once as the guardian of the spiritual well-being of the Métis and as the prophet and priest of a new form of Christianity. He based much of this belief on a supportive letter he received from Bishop Ignace Bourget of Montreal on 14 July 1875, in which the bishop stated: “I have the deep-seated conviction that you will receive in this life, and sooner than you think, the reward for all your mental sacrifices. . . . For He has given you a mission which you must fulfil in all respects.” Riel already had experienced a mystical vision and an uncontrollable emotional seizure during a visit to Washington, D.C., in December 1874, and at Keeseville, Abbé Martin’s household was being terrified by Riel’s continuous shouting and crying. Unable to give him solace, the kindly priest appealed for help to Riel’s uncle, John Lee, who lived near Montreal. Riel stayed with the Lees for several months, until his continued religious mania finally resulted in the interruption of a church service. The unbearable strain on his household induced Lee to consult Riel’s political friend, Doctor Lachapelle, who arranged for Riel’s admission to the asylum at Longue-Pointe (Hôpital Louis-H. LaFontaine, Montréal) on 6 March 1876, under the name Louis R. David.

The supervising doctor, Dr Henry Howard, agreed that confinement was the only course available to Riel’s friends. However, Howard was much impressed by Riel’s intelligence and knowledge of classical philosophy, the varieties of Christian belief, and Judaism. In commenting on Riel’s peculiar theological ideas, he later wrote: “I never could satisfy myself thoroughly as to whether this sort of talk was not acting a part or an hallucination.” During his brief stay at Longue-Pointe Riel continued to alternate between periods of lucidity and irrationality. The sisters in charge of the asylum feared that his political enemies would discover his presence and in May 1876 Lachapelle certified that Riel required constant attention and treatment which could only be provided in the Beauport asylum (Centre hospitalier Robert-Giffard) outside Quebec City. At Beauport Riel brooded on his mission and also occasionally became violent and excited. He wrote notes elaborating his theological principles, which were a fantastic mélange of Christian and Judaic ideas. But in time, although he could still be irrational on religious and political subjects, rest and calm had their effect. After a little more than a year and a half the medical superintendent of Beauport, Dr François-Elzéar Roy, discharged Riel with a warning to live a quiet life – if possible an outdoor life.

For the balance of 1877 and much of 1878 Riel was at Keeseville and other centres where he hoped to find work. Late in 1878 he went to St Paul. He discovered that many of the Métis in Manitoba had sold their land to Winnipeg land speculators because they had no funds or skill to farm, and had moved to the valleys of the Saskatchewan and upper Missouri to hunt the now scarce buffalo. Riel travelled to the Canadian border, where he was visited by friends and members of his family; he learned that the Métis did not believe he had ever been insane, despite his sojourn in two Quebec asylums. He confided to a few friends that he had pretended to be mad.

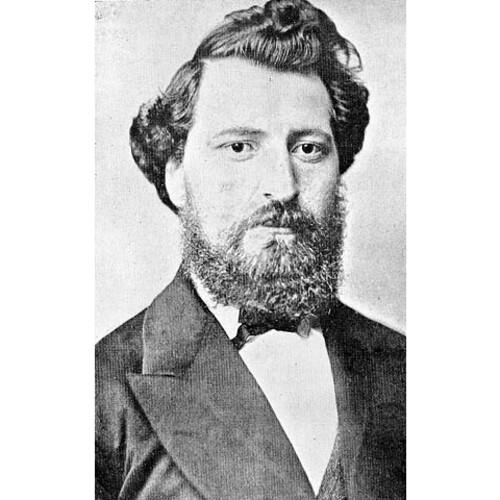

With his exile still a year to run, Riel joined those Métis who, along with Indians of the Canadian plains, were wandering in the upper Missouri area of Montana territory, and he became a trader and interpreter. He found widespread economic hardship and demoralization among the Métis in this turbulent frontier area. At this time Riel, bearded and handsome, was in the prime of life. In 1881 he married a Métis girl, Marguerite Monet, dit Bellehumeur. He had had a passionate love affair with Évelina Martin, dit Barnabé, sister of the parish priest of Keeseville, but despite her desire to join him in Montana, Riel had broken the engagement, apparently because he could offer her no suitable home in the circumstances under which he was forced to live.

Riel soon involved himself in the turbulent politics of Montana, in spite of the warning that he should live a quiet life. He associated himself with the local Republican party because it seemed to be the best hope for procuring a reserve for the Métis and for curbing the whisky trade which was demoralizing his people. Appointed a deputy to fight this trade, Riel also participated in the 1882 congressional election. His involvement in the election subsequently produced a worrisome court case about vote manipulation, but in the end the charges against Riel were dismissed for insufficient evidence. In March 1883 he became an American citizen. That June he visited Winnipeg but returned to Montana determined to throw in his lot with his people there. In 1884 he accepted an invitation from the Jesuits to become the teacher at St Peter’s mission on the Sun River, a tributary of the Missouri. He was a good teacher and conscientious, though as the months passed he became restless and bored by the routine.

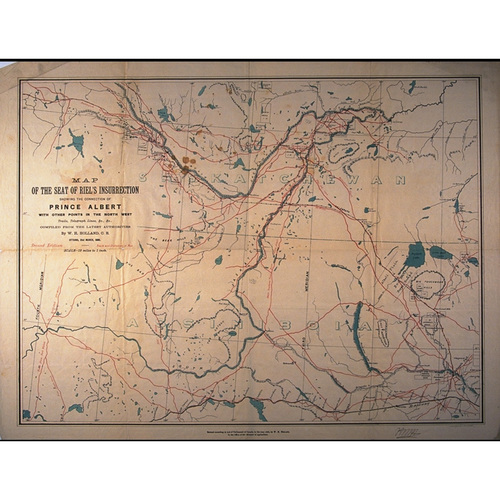

But his people in the northwest did not forget him. It is not clear who in the District of Lorne was most influential in soliciting Riel’s assistance with their grievances against the Canadian government. Gabriel Dumont*, the famous buffalo hunter, who had apparently met Riel at Red River in 1870, had been the recognized leader of the Métis community at Saint-Laurent (Saint-Laurent-Grandin, Sask.) since the early 1870s. His agreement with those who wished to solicit Riel’s help, namely the Ontario settler William Henry Jackson* and English-speaking mixed-blood Andrew Spence of Prince Albert (Sask.), carried great weight, especially when he himself became one of the delegates who went to Montana to contact Riel in June 1884. The invitation to come to the South Saskatchewan offered Riel an opportunity to lead his people, a mission he had cherished for a decade. He agreed to assist in presenting the grievances of the district to the Canadian government and added that he would use this opportunity to pursue his personal claim for land in Manitoba. The delegation accepted these terms, and Riel left Montana confident that God would give him the success he longed for and that he would return home in September to continue his fight for the Métis there.

When Riel reached Batoche (Sask.) in the District of Lorne at the beginning of July 1884 he found an unhappy and angry population – white, Indian, and Métis. The relocation of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s main line in the southern prairie region had produced a collapse of land values in nearby Prince Albert. Settlers did not hold clear title to their land despite the fact that many had lived for over three years in the district. For the more than 1,400 Métis in the area, the questions of unextinguished Indian rights to the land and the land surveys were the major issues. These Métis had been semi-nomadic hunters, living far west of the Red River, who had not participated in the events of 1869–70. With the disappearance of the buffalo and with the encouragement of the missionaries, they were now beginning to settle into farming communities. Those who had settled first obtained the traditional and much preferred river lots; but after a federal survey in 1882 Métis settlers were forced to occupy square lots, and the federal government was refusing to re-survey the area.

Agitation for redress of grievances by white settlers had begun as early as 1883 with the formation of the Manitoba and North West Farmers’ Co-operative and Protective Union to petition the federal government. That same year the Settlers’ Union was formed by the Lorne radicals, and Jackson, its secretary, had been commissioned to contact the Métis of Saint-Laurent. Dumont had been cooperative, and in March 1884 had urged the preparation of a “list of rights,” though some of the more militant Métis suggested action by force of arms. Yet in July, when Riel addressed meetings, first of Métis at Charles Nolin’s house at Batoche, then of several hundred English-speaking settlers at Red Deer Hill, he impressed everyone with his moderation. About a week later he went to another meeting, where most of Prince Albert was in attendance, and again advocated a peaceful presentation of grievances and proposals. Riel’s calmness and moderation gained him the support of most settlers, and put him in a position of some influence.

Meanwhile the Plains Cree leader, Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa], and his followers, assembled in June 1884 on the reserve of Poundmaker [Pītikwahanapiwīyin], were formulating demands to be made to the Indian Affairs branch of the federal government. Poundmaker and Big Bear were aware of the agitation in Lorne and held meetings with Riel soon after his arrival in the district. However, the native peoples’ grievances had little in common with those Riel now represented, and these meetings did nothing to bring the two movements closer together.

The early favourable response to Riel among the white settlers yielded to growing opposition. The Prince Albert Times and Saskatchewan Review reversed its editorial policy, having been bribed by Edgar Dewdney*, the Indian commissioner and lieutenant governor of the territories. In addition, Riel did not have the support of the clergy. Father Alexis André* charged Riel with mixing religion and politics. On 1 Sept. 1884 Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin* of St Albert paid a conciliatory visit to Saint-Laurent, accompanied by Amédée-Emmanuel Forget*, secretary to Dewdney; there is some evidence that Forget attempted, unsuccessfully, to “buy” Riel with a seat on the Council of the North-West Territories. Dumont calmed events somewhat by explaining: “We need him [Riel] here as our political leader. In other matters I am the chief here.” Riel explained to Grandin what he wanted: “the inauguration of a responsible Government”; “the same privileges to the old settlers of the North-West Territories as those accorded to the old settlers of Manitoba”; the granting of “the lands, at present, in possession of the Halfbreeds” to them “in fee simple,” and the issuing of patents to them “on application”; 240 acres for all mixed-bloods; the income from the sale of two million acres for the support of schools, hospitals, and orphanages and for the purchase of ploughs and of grain; and for all “works and contracts of the Government in the North-West Territories be given, as far as practicable to residents therein, in order to encourage them as they deserve and to increase circulation of cash in the Territories.”

Riel and Jackson busied themselves at Prince Albert with the petition, and on 16 December it was sent to Ottawa, signed by Andrew Spence as chairman and Jackson as secretary of the joint English-Métis organization. The petition was a long one with 25 sections, land claims occupying a prominent place. The grievances of the Métis and Indians were recited and it was noted that while the territories had a population of 60,000, Manitoba had been granted provincial status with only 12,000. The petitioners thus included the suggestion that they “be allowed as in [1870], to send Delegates to Ottawa with their Bill of rights; whereby an understanding may be arrived at as to their entry into confederation, with the constitution of a free province.” The petition was acknowledged by Chapleau, the secretary of state, and was referred to David Lewis Macpherson*, the minister of the interior, by Macdonald, the prime minister, who subsequently denied having received it. The acknowledgement by Chapleau was regarded by Jackson as a victory.

The question now arose for Riel as to whether or not to return to Montana as he had originally planned. At the same time he had not forgotten that his own land claims had not yet been settled by the federal government. Certainly he was a poor man who lived by charity and he had not hidden from the delegation the fact that he wished to press these claims: under the Manitoba Act, he pointed out, 240 acres were owing to him. He also had owned five lots which were of value for their hay, wood, and proximity to the Red River. He estimated that in all he was owed a sum of $35,000. However, the federal government remained insensitive not only to Riel’s claims but to the grievances of the petition.

By the end of February 1885 Riel had agreed to stay, claiming that “a vast multitude of nations” was waiting to support him. However, although the missionaries were sympathetic to the Métis cause they opposed any use of force or any encouragement of the Indians; by March Métis frustration had led to talk of resort to arms. Because of the opposition from the clergy and from some Métis, including Nolin, to violence, on 10 March the Métis decided to begin a novena, timed to end on the 19th, feast day of St Joseph, the patron saint of the Métis, to assist them in arriving at a decision. But, during a mass in the church at Saint-Laurent on 15 March, Riel remonstrated with the priest, Father Vital Fourmond, on his attitude to a Métis armed movement, in effect making a final break from the church. He was becoming more and more mystical and pietistic, and he spent much time in prayer. He deepened his rupture with the clergy by preaching his own theology to his followers; he renamed the days of the week, put the Lord’s Day on Saturday as in Mosaic law, proposed that there be a new pope (Bourget, and later Taché), rejected the rule of Rome, and suggested that everyone would be priests in a new reformed Catholicism.

Frustrated by the lack of federal action, Riel was, in fact, having a renewed period of mental disturbance. But the appeal of his charismatic personality was strong, and by this time his more militant followers were seizing shotguns, rifles, and ammunition. On 18 March, hearing a rumour that 500 North-West Mounted Police were advancing towards them, Riel and approximately 60 supporters ransacked stores and seized a number of people, including Indian Agent John Bean Lash, near Batoche. Riel announced that “Rome has fallen” and that Bourget was the new pope. That evening at Saint-Laurent he signed his name Louis “David” Riel, and the next day he formed a provisional government, composed of 15 councillors, known as the “exovedate,” which meant “those picked from the flock.” Riel was not a member; to be one would not have fitted his role as a prophet by divine sanction.

Riel was nevertheless the undisputed leader of the movement, Dumont being the military head. Their intention was first to take Fort Carlton, and they tried without success to enlist the active support of the English-speaking mixed-bloods. Needing supplies for his troops, Dumont ransacked a store at Duck Lake on 25 March. He then proceeded west and the next day encountered by chance a force commanded by NWMP Superintendent Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier*. Despite the fact that the Métis were protected by natural cover and occupied high ground, Crozier, an impetuous and excitable officer, gave the order to fire. Of the government’s 100 men, 12 were killed and 11 wounded. The Métis lost only five of about 300 men. If Riel, who had given the order to return the fire from the police, had not stopped the fighting, the government forces would have been annihilated. Riel and his followers spent the rest of the day in prayers for their dead, returning to Batoche on 31 March.

By early April Riel had given up hope of support from the English half-breeds and the whites, although he did still expect to be able to make alliances with the various Indian groups, who by this time had also taken up arms. At Battleford, Poundmaker’s followers had broken into the buildings in the town, and the residents had been forced to take refuge in the NWMP barracks. At Eagle Hills the Stonies had killed a white farm instructor. On Big Bear’s reserve the war chief, Wandering Spirit [Kapapamahchakwew], had displaced Big Bear and led the band in the violent attack on Frog Lake (Alta) on 2 April, where nine people were killed [see Léon-Adélard Fafard]. Riel sent messages to the Indians to join the Métis movement, but chronic factionalism among the various Indian groups and a lack of understanding of Riel’s goals produced only a few recruits. The Indian movement itself was never able to put up a united front, despite Big Bear’s efforts in this direction, and lack of concerted action was a major cause of its collapse.

The events at Frog Lake, although the responsibility of the Indians and not the Métis, aroused horror and hatred of Riel throughout English Canada. That both Métis and Indians had legitimate grievances was ignored. Macdonald decided to crush the revolt, calling on Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton*, then commanding the Canadian militia, to take the field. Middleton formulated a simple plan: he would march on Riel at Batoche from Fort Qu’Appelle (Sask.); at the same time Major-General Thomas Bland Strange* would march from Calgary to engage Big Bear, and proceed to join forces with Middleton; and Lieutenant-Colonel William Dillon Otter* was to relieve Battleford. Otter was successful, but suffered a serious setback at Cut Knife Hill (Sask.) at the hands of Poundmaker’s warriors. Middleton was fired on by the Métis at Fish Creek (Sask.) on 24 April and was not able to continue his march to Batoche until 7 May.

The Métis were preparing their defences at Batoche, a series of pits skilfully hidden in the bush. Dumont, too realistic to believe that his forces could defeat the Canadians, had hoped that a well-conducted guerrilla campaign would force the government to negotiate. Riel had opposed these tactics and had decided upon concentrating their forces, about 175 or 200 men, at Batoche – in his mind the city of God. When Middleton’s force of more than 800 men advanced on the village on 9 May, the result was a foregone conclusion despite what the English Canadian press later called the heroics of the militia led by Colonel Arthur Trefusis Heneage Williams. The battle, and the rebellion, was over on 12 May.

Dumont fled to the United States; on 15 May Riel, “cold and forlorn,” chose to surrender to the scouts of the NWMP, who described him as “careworn and haggard; he has let his hair and beard grow long; He is dressed in a poorer fashion than most of the half breeds captured. While talking to Gen’l Middleton as could be seen from the outside of the tent, his eyes rolled from side to side with the look of a hunted man; He is evidently the most thoroughly frightened man in camp . . . .” On the following day the minister of militia, Adolphe-Philippe Caron*, instructed Middleton to send Riel to Winnipeg under guard for trial, but Macdonald and his cabinet came to realize that if the trial was held in Winnipeg a unanimous verdict might not be secured, a distinctly unpleasant prospect for the government. When the party reached Moose Jaw (Sask.) on the CPR, it was redirected by Caron to Regina, where it arrived on 23 May 1885. In the territorial capital and its neighbourhood, hostility to the prisoner prevailed.

The difference in site also meant a different court procedure. Under Manitoba law a prisoner was entitled to a 12-man jury and half the jury might be French-speaking. On the other hand, the federal law governing court procedure in the territories called for only a six-man jury, with no assurance of bilingual rights. Moreover, at a trial held in one of the provinces the case would be heard by a superior court judge whose independence was guaranteed by law and practice. Instead, Riel was tried in Regina by a stipendiary magistrate who held office at the pleasure of the federal government, and could be dismissed without cause at any time.

It was clear from the start that the trial would be a political one, and there is indisputable evidence that Macdonald’s objective was to fix exclusive responsibility on Riel and to secure his conviction and execution as soon as possible. It was an understandable reaction to the inflamed opinion of Ontario, which cried for vengeance for the killing of Thomas Scott, the whites at Frog Lake, the men at Duck Lake, and the militiamen under Middleton’s command. But Macdonald sadly misjudged the explosion of emotions in Quebec. In the event, the government’s conduct of the case was to be a travesty of justice.

When Riel was brought to Regina he was imprisoned in the NWMP barracks in a 6½ by 4½ foot cell and shackled with ball and chain. All the defendants who were charged, including Jackson who had joined the Métis movement, were held incommunicado by the police until the chief prosecuting attorneys arrived on 1 July. In the interval, the government’s lawyers were sifting the evidence against Riel and the others, and preparing the formal charges, utilizing the documents which had been retrieved from Riel’s headquarters and on the battlefield.

The presiding magistrate was to be Hugh Richardson*, an Englishman who had been named a stipendiary magistrate by the Mackenzie administration in 1876 and who was a member of the Council of the North-West Territories and legal adviser to the lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories. He was not bilingual. The five prosecuting attorneys were the deputy minister of justice, George Wheelock Burbidge*, as well as leading members of the bar of eastern Canada: Christopher Robinson*, Thomas Chase-Casgrain*, Britton Bath Osler*, and David Lynch Scott*. François-Xavier Lemieux*, a successful criminal lawyer, was one of those who agreed to defend Riel, along with Charles Fitzpatrick*, Thomas Cooke Johnstone, and James Naismith Greenshields*, also leading members of the bar in the east.

In retrospect, the defence lawyers’ handling of Riel’s case left much to be desired. They did not ask for dismissal on grounds of insanity, despite the fact that Jackson had been so acquitted a few days before. They also denied Riel the right to cross-examine witnesses, even though (as Riel put it during the trial) “they lose more than three-quarters of the good opportunities of making good answers . . . ,” because they did not know the witnesses and the local circumstances. All this was a serious invasion of the prisoner’s rights by his counsel. Lemieux also declared that the defence counsel would not be responsible for anything the prisoner might say during his first address to the jury. It is curious that Riel’s lawyers did not demand that he be tried under the Canadian statute of 1868, which would have allowed a charge of treason-felony with life imprisonment as the penalty. Of the 84 trials held in Battleford and Regina for participants in the rebellion, 71 were for treason-felony, 12 for murder, and only one, Riel’s, for high treason. The charge against Riel was under the medieval English statute of 1352, which carried a mandatory death penalty.

The trial opened on 20 July with the reading of the indictment, followed by arguments by Riel’s counsel challenging the jurisdiction of the court and the trial procedure. Richardson rejected the defence arguments. Riel pleaded not guilty. On the following day the defence counsel argued for a postponement of the trial, on the grounds that they would be unable to conduct a defence in the absence of certain witnesses, including a number of alienists in eastern Canada. Richardson granted postponement for one week. Riel had asked for three witnesses who had fled to Montana, Gabriel Dumont and two other Métis, Napoléon Nault and Michel Dumas. Father André and his associate Father Fourmond did appear as defence witnesses, but not Lawrence Vankoughnet, the superintendent-general of Indian affairs, and Alexander Mackinnon Burgess*, deputy minister of the interior, who, Riel argued, were custodians of documents which detailed Métis grievances. The third day’s proceedings began on 28 July with the empanelling of the jury. As a measure of the inevitability of the final outcome it should be noted that of the 36 persons summoned by Richardson for jury service only one was French-speaking, and he was prevented by an accident from appearing. The crown challenged one prospective juror, the only Roman Catholic on the list. Thus, despite the fact that French Canadian and Métis jurors could have been secured from among the population of the territories, Riel was tried by a jury comprised entirely of English-speaking Protestants.

A perusal of the evidence indicates clearly that the crown selected witnesses who would testify that the prisoner had used his great influence with the Métis to lead them to arm themselves, and subsequently had determined the strategy of the uprising. Dumont, the witnesses implied, had been responsible only for the tactics adopted in the engagements. The prosecution elicited opinions from its witnesses that Riel’s deep religious fervour was calculated to impress a simple-minded folk who had become his dupes and it made much of Riel’s negotiations with the Indians. It also represented the prisoner as a self-seeking villain who was prepared in return for $35,000 to abandon the cause of the Métis. The prosecution sought to discredit witnesses called by the defence, and objected to the admission of evidence on the failure of the federal government to deal with long-standing complaints. It may well have feared the effect of such evidence on the jurors because even at this early date most westerners felt alienated by policies made in Ottawa for the benefit of central Canada.

Both Father André and Father Fourmond, questioned on Riel’s behaviour, politics, and religion, were unshakeable in their opinion that Riel was insane. Defence counsel’s star witness was Dr François-Elzéar Roy, superintendent of the Beauport asylum, who stated that Riel suffered from megalomania (today often referred to as paranoia). Roy was subjected to a savage cross-examination by Osler, whose questions implied that Roy had a financial interest in keeping patients in his custody. Dr Daniel Clark*, superintendent of the lunatic asylum in Toronto, testified that Riel was insane, but admitted he would have to have him under observation for some months before he could be positive that he was not malingering. Clark was highly critical of the McNaghten rules; this legal precedent established that a defence of insanity could be accepted only if it could be proved that the accused did not know the difference between right and wrong. To combat the impressive evidence of Riel’s insanity the crown counsel resorted to extraordinary measures. Dr James Wallace, medical superintendent of the insane asylum in Hamilton, Ont., testified that Riel was sane, on the basis of about half an hour’s interview and listening to the trial proceedings. Not only was his examination superficial, but defence counsel Charles Fitzpatrick elicited that Wallace had never read the works of the leading French authorities on megalomania. Dr Augustus Jukes, the NWMP surgeon, was forced to admit under defence questioning that one could converse with a man and not be aware of insanity. With its case in such a precarious state, the prosecution recalled General Middleton and four other laymen who had had brief contacts with Riel.

The defence counsel could have made better use of Dr Clark’s evidence, though it may have been that they had little or no experience in dealing with cases of insanity, or they may have had too little time to prepare their defence or to consult alienists in advance. Yet another curious feature of the conduct of the case was that the defence did not attempt to subpoena the diary which Riel kept between March and May 1885 and which was picked up on the battlefield along with his other papers and shipped to the Department of Justice in Ottawa. The Toronto Globe had published most of this diary by the time the trial began in Regina. The diary displays a curious mixture of prayers and pious assertions with religious interpretations of the events of the rebellion.

Fitzpatrick summed up the case for acquittal in perhaps the most passionately eloquent address ever heard in a Canadian courtroom. The first part was devoted to an exposition of the historic role of the Métis in the northwest, and the disabilities under which they had suffered. The remainder dealt cogently with Riel’s actions during the rebellion, which were held to be incompatible with those of a sane man. The address had a profound effect on those present in the court, including the jurors. The judge then called on Riel, asking him whether he had anything to say. Riel would have preferred to defer his remarks until after the crown counsel had made its summation, but the judge denied the request. Riel then proceeded to address the court. The intense religiosity of the prisoner, a notable feature of his personality, was evident from the beginning and throughout his remarks. He spoke in a clear, eloquent, and earnest manner and dealt particularly with the question of his insanity. The address was quite rational in its description of the undemocratic institutions which prevailed in the territories. Robinson’s summation for the prosecution was relatively brief and unemotional, and was chiefly concerned with the defence that Riel was insane. “My learned friends,” he sagely observed, “must make their choice between their defences. They cannot claim for their client what is called a niche in the temple of fame and at the same time assert that he is entitled to a place in a lunatic asylum.” Riel, he continued, “is neither a patriot nor a lunatic.” How could a man live for 18 months as the most prominent man in the district without his insanity being detected? Robinson could find no evidence that Riel controlled his mania and used it for his own purpose. Finally, Robinson was dissatisfied with the evidence that had been provided by the defence concerning the circumstances of his incarceration in the two asylums.

The judge’s charge to the jury was clearly biased against Riel. Richardson reiterated his claim that the court had full jurisdiction. In dealing with the question of insanity he suggested that Riel’s claim for $35,000, and the disappearance of his irritability when brought to Regina, were facts which demonstrated reasoning power. Richardson concluded by asking the jury to apply the McNaghten rules to the case. On 1 August the jury returned a verdict of guilty with a recommendation of mercy. Richardson passed the death sentence.

But before delivering the sentence Richardson asked Riel the customary question of whether he had anything to say to the court. Riel seized the opportunity to deliver a much longer speech than the one he had made the previous afternoon. It was an entirely secular argument, with the exception of three brief references to the Deity, to his prophetic mission, and to the spirit which had guided his activities. He began by expressing satisfaction that he had not been regarded as insane. He then turned to a recital of the Manitoba disturbances of 1869–70, two-thirds of his remarks being devoted to this theme. Turning to his ambitions for the northwest, he described the policy he would follow if he were federal minister of immigration and his programme for settling the prairies. In essence it was a not unreasonable programme for creating a multi-cultural society. At the same time the address has shrewd observations and moving passages which typify the rhetorical power that had given him such an influence in the Métis community.

The verdict was appealed to the Court of Queen’s Bench of Manitoba (the appeal court for the territories), and subsequently to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, but the appeals were dismissed. Meanwhile, petitions for the commutation of the death sentence flooded into Ottawa from thousands of French Canadians in Quebec, Massachusetts, and Manitoba. A considerable number of counter-petitions were sent from Ontario. The commutation petitions were based on the argument that Riel was insane and hence not responsible for his actions during the rebellion, or that his crime was a political one for which civilized nations no longer exacted the death penalty. Riel’s fate had become a national issue that threatened to divide the cabinet, indeed the country, and a vast amount of editorial commentary was produced on the subject. Ontario newspapers favoured the execution and at least one, the Toronto News, went as far as to begin advocating polarization of politics on racial lines. On the other hand, Quebec journalists were highly critical of Macdonald and his cabinet, especially his French Canadian colleagues. Despite the immense pressure from mass meetings in Quebec, Chapleau, Hector-Louis Langevin*, and Caron did not resign, perhaps saving the country from further racial and religious conflict.

As a result of the insistence of Macdonald’s French Canadian cabinet colleagues, he nevertheless agreed to have Riel re-examined. On 31 Oct. 1885 three doctors were instructed to report to the government on whether the prisoner was a reasonable and accountable being who could properly be executed. They were Dr Jukes of Regina, Dr François-Xavier Valade, a well-known general practitioner of Ottawa, and Dr Michael Lavell*, a specialist in obstetrics and warden of the Kingston penitentiary. Lavell and Jukes reported that Riel was sane. Valade’s conclusion was that Riel was not an accountable being, that he was unable to distinguish between right and wrong on political and religious subjects. The whole consultation was undertaken in the utmost secrecy. Valade’s testimony was falsified by the ministry in the report submitted to parliament in 1886 to make it appear that he had in fact agreed with the other two.

In general, the treason charge was a legal rationalization. But even if treason had been a sound charge, there were grounds for commuting the sentence in view of the conflicting testimony on Riel’s sanity, the dictates of mercy, and the political character of the prosecution. In its political calculation, the government sadly misjudged the situation. French Canadians understandably would be suspicious of court decisions which had acquitted the two white settlers, Jackson and Thomas Scott, both tried for treason-felony, while finding 20 Métis and numerous Indians guilty. Perhaps nothing else could have been expected from the 70-year-old Macdonald, bereft of an outstanding French Canadian colleague. On 16 November at the NWMP barracks in Regina, Riel was hanged, meeting his death with dignity, calmness, and courage.