Source: Link

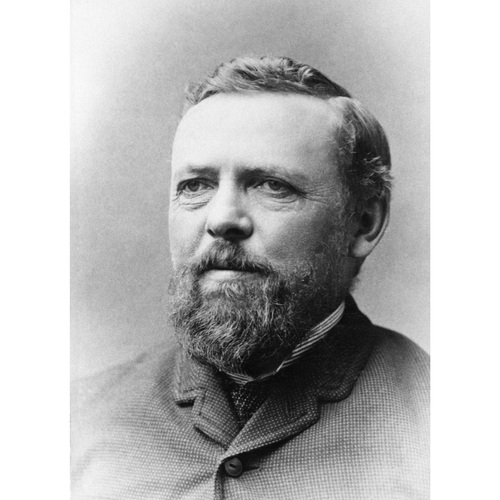

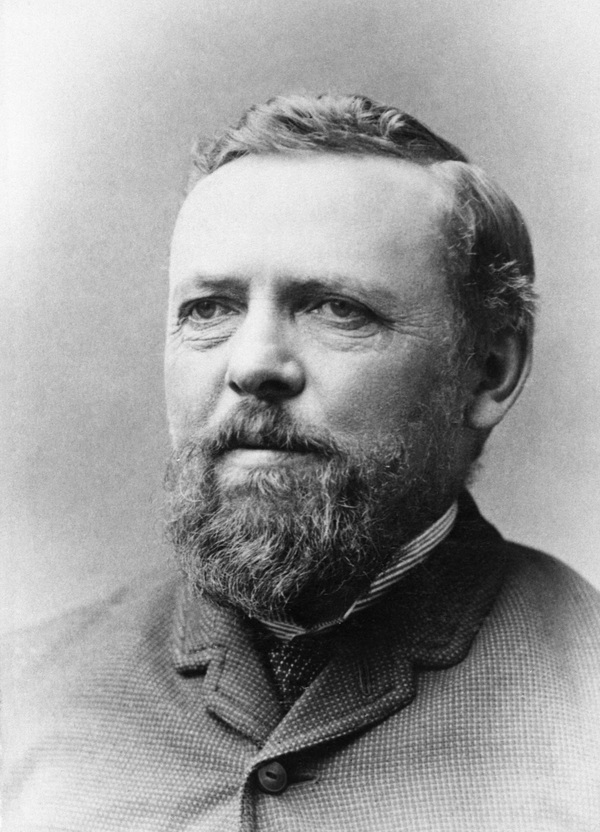

PEARCE, WILLIAM, surveyor, civil engineer, public servant, and statistician; b. 1 Feb. 1848 in Dunwich Township, Upper Canada, son of John Pearce and Elizabeth Moorhouse; brother of John Seabury Pearce*; m. 20 Sept. 1881 Margaret Adolphine Meyer in McKillop Township, Ont., and they had five sons, two of whom died in infancy, and two daughters; d. 3 March 1930 in Calgary.

William Pearce was born on the edge of Upper Canada’s settled frontier near Tyrconnell, on Lake Erie. Taken from school at age 12 to help clear the family property, he later returned and eventually enrolled in the engineering course at the University of Toronto, probably in 1868. After a year of study there and three years’ apprenticeship with the Toronto engineering firm of Wadsworth and Unwin, he gained certification as an Ontario land surveyor in 1872. The skill he displayed on the complex Thousand Islands survey the following year impressed his senior colleagues, among whom was the dominion surveyor general, John Stoughton Dennis*, who asked Pearce to join his staff for work in Manitoba and the North-West Territories. He thus became a dominion land surveyor in 1874, and in 1875 he was appointed to the board of examiners for dominion land surveyors.

Employed on a series of one-year contracts through the mid 1870s, Pearce was engaged in establishing legal subdivisions in the Winnipeg area, where he gained recognition for his competence in dealing with the difficult and politically charged matter of conflicting Métis land claims [see Donald Codd*]. He also helped initiate the meridian, baseline, and township grid surveys that would occupy teams of dominion land surveyors for the next 30 years. It was while involved with these tasks in the Turtle Mountain area in southwestern Manitoba that Pearce took it upon himself to advise his supervisors on land-use policy. Observing the activities of the first wave of homesteaders in the area and what he deemed to be the misappropriation of vital resources by first arrivals, he urged that the government exercise its authority under the Dominion Lands Act of 1872 to reserve large tracts containing scarce timber and water. In Pearce’s view, such valuable lands should be held for the use of bona fide farmers rather than surrendered for the private advantage of speculators and a handful of commercial enterprises. It remained his firm conviction throughout his career that it was in the public interest to ensure that lands and resources were developed in a manner benefiting the majority, even if such a policy meant restricting commercial enterprises or the rights of individual property holders. In this regard, Pearce envisaged a degree of government intervention that ran against the laissez-faire spirit that predominated amongst those settling in the west.

The opportunity to carry this point of view into practice was afforded with Pearce’s appointment in February 1882 to the position of inspector of dominion lands agencies, which along with the office of commissioner of dominion lands constituted the newly formed Dominion Lands Board within the Department of the Interior. The board’s primary responsibilities were to supervise Dominion Lands offices in prairie communities and ensure that there was uniform compliance with the law by local agents, to adjudicate all land disputes, and to advise the government on the development of lands and resources. The board opened its Winnipeg office in March and with characteristic energy Pearce began a series of inspections. The trail of dismissed agents, evicted squatters, and public figures called to account for land speculation that followed soon made him a respected but controversial figure with some powerful enemies, especially Frank Oliver*, owner and editor of the Edmonton Bulletin. If Pearce was motivated by a deep sense of mission, he was also inclined to be authoritarian and blunt. There would be times when his insistence on strict compliance had to be curbed by his political masters.

Given the duties of his office, his past experience in Manitoba, and his reputation for meticulous documentation, Pearce was called upon in 1883 to investigate the land claims of settlers and Métis along the North Saskatchewan River between Battleford and Prince Albert (Sask.). His failure to complete this large and complex task before 1885 [see Sir David Lewis Macpherson*] was seen by some at the time, and others subsequently, as having been a factor in the North-West rebellion [see Louis Riel*]. Following the uprising, Pearce was directed to undertake a comprehensive study of the causes leading up to it and assess the federal government’s responsibility. His 1886 report absolving the government of blame did not impress the Liberal opposition. Seen by his opponents as a Conservative, Pearce himself refused to be labelled. In a letter to Clifford Sifton in 1897, he would declare that, to ensure public trust, he had never cast a vote for any federal, territorial, or municipal candidate or attended a political meeting since the date of his entry into public service.

As construction on the Canadian Pacific Railway advanced into the Rocky Mountains in 1884 and applications for mineral rights to nearby properties began to materialize, Ottawa became convinced that a mining and land boom was about to commence and proposed the establishment of a senior Department of the Interior officer in Calgary whose specific responsibility would be to administer the development of the region’s timber and mineral resources. The individual chosen for this new position, superintendent of mines, was William Pearce, who was appointed on 15 May. Already one of a handful of federal civil servants with real power in the west, Pearce emerged now as an even more influential figure. As superintendent, he reported directly to the deputy minister of the interior (until early 1897, Alexander Mackinnon Burgess*) and was almost an independent authority with free rein to exercise his considerable energy and talent over the federal land known as the railway belt, which straddled the CPR’s main line from the Red River valley to the Rockies and into British Columbia. It is not hard to understand why Pearce was known to some of his detractors as “Czar of the West.” As both a member of the Dominion Lands Board and superintendent of mines, he was responsible not only for administering, but also for formulating, the regulations governing the future development of resources in the North-West Territories.

Although the redrafting of federal mining regulations occupied Pearce’s attention initially, the mining boom failed to materialize and his energies were redirected to other issues. The first of these emerged with competing claims to the newly discovered mineral hot springs near Banff (Alta), claims that Pearce in 1886 was called upon to evaluate. With others, Pearce had concluded that the springs should be retained by the crown, and he had played an important part in having the area set aside in 1885 for public use. Afterwards, using phrasing similar to that found in America’s Yellowstone National Park Act of 1872, he drafted the 1887 statute creating Canada’s first national park, Rocky Mountains Park. Pearce was subsequently instrumental in setting aside and determining the boundaries of what later became Yoho and Glacier national parks in British Columbia. Anticipating Calgary’s future growth, he also set aside St George’s and St Patrick’s islands, along with the opposite north bank of the Bow River, as future parkland.

As much as Pearce was attracted to the notion of reserving exceptionally scenic areas, he soon came to see water management as a more urgent area of concern. A witness to the severe drought that began in the late 1880s, he became convinced that the future of the prairies was dependent upon the proper distribution of the region’s limited water supply. The government should therefore take over the management of this precious resource. Pearce’s thoughts in this regard were greatly influenced by his travels in the American west, as well as by the writings of John Wesley Powell, the distinguished head of the United States Geological Survey, and Elwood Mead, America’s pre-eminent authority on irrigation and water law, both of whom advocated government management of water in the arid west.

Believing that most of southern Alberta and western Assiniboia was too dry for cereal agriculture and better suited to grazing, Pearce advised the restriction of homestead settlement in favour of measures that supported the already well-established cattle industry. In 1886 the government, under Pearce’s direction, began to set aside for public use select springs and strategic locations along creeks, rivers, and lakefronts. Intended to prevent homesteaders and large cattle companies from denying access to a vital resource, the network of stock-watering reservations established over the following decade was important in helping cattlemen to fend off the initial tide of prairie settlement that followed Clifford Sifton’s immigration campaign at the turn of the century.

Managing water in support of the cattle industry was but a preliminary step towards Pearce’s real objective, comprehensive government management of the region’s entire water supply. While he considered open settlement in the grazing region undesirable, he was aware that there were large tracts of fertile land within the dry belt that were well suited to irrigation. He calculated, however, that the available water was sufficient to irrigate only a fraction of such lands. It therefore seemed obvious to him that continued development of the dry country hinged upon progressive irrigation legislation.

With unrelenting energy, Pearce set about the task of converting community leaders, politicians, and senior federal bureaucrats to the cause. He faced a formidable challenge. It was not so much that irrigation was a hard sell, given the ongoing drought. Rather, it was the nature of the legislative foundation that Pearce wanted to put in place to support it. Instructed by what he had seen in the American west, where a complex patchwork of state and federal laws based upon different water-law doctrines clogged the courts with litigation and made efficient and equitable distribution of water all but impossible, Pearce argued that the key to progressive management lay in vesting the federal government with the ownership of water. This proposal to abolish all private claims to water other than for domestic use flew in the face of the ancient Anglo-Saxon doctrine of riparian rights, was highly controversial, and made Pearce’s civil and political masters very nervous. In the end, the continuing drought, an awareness that since the North-West Territories remained sparsely settled there was a moment of opportunity to act before private rights were extensively established, and Pearce’s skilful mobilization of regional support pushed his cautious colleagues to move forward. Drafted by Pearce, the North-west Irrigation Act won parliamentary approval in July 1894. It transferred ownership of water throughout the territories to the federal government, enshrined the notion of water as a public resource, privileged community rights over private rights, and enabled federal bureaucrats to manage water in the public interest. Held up by Elwood Mead and other American authorities as a model of enlightened legislation, the act set water management in the Canadian prairie west on a course distinct from practice elsewhere on the continent and it stands as the foundation of contemporary water law in Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Pearce's vision of an irrigated Eden now rested upon the construction of a network of dams, reservoirs, and trunk canals. Unable to convince Ottawa that the government should build this infrastructure, Pearce had initiated discussions with William Cornelius Van Horne*, who headed one of the few private organizations, the CPR, capable of undertaking a project of this scale. Aware that the Canadian government still owed the railway nearly four million acres to fulfil its charter obligations, and that the only significant remaining block of unclaimed prairie was in that portion of the arid district which bordered the CPR's main line between Medicine Hat (Alta) and Calgary, Pearce seized upon irrigation as the vehicle to enable the railway and the government to resolve the issue. His persistence was instrumental in the transfer to the railway, in August 1903, of more than 3.5 million acres, 2.9 million of which formed a compact area known as the "irrigation block." The CPR began construction on the main canal leading from the Bow River just east of Calgary in 1904, thus launching one of North America's largest irrigation and colonization schemes that included a program of assisted settlement along the lines that Pearce had envisioned. Pearce had also been instrumental in 1896 in enabling Elliott Torrance Galt to consolidate land for irrigation east and south of Lethbridge.

From the outset Pearce understood his irrigation legislation as but an initial step requiring several complementary measures. The most contentious of these called for the creation of a vast forest reserve to protect the headwaters of streams and rivers flowing onto the prairie from the Rocky Mountains. Eventually, in the face of resistance from logging, grazing, and settlement interests, the Foot Hills Forest Reserve (Alta) was established in 1898. Embracing all of the territory from the summit of the Rockies to the prairie and extending northward from the international boundary to the Bow River, this immense reserve, known after 1912 as the Rocky Mountain Forest Reserve, remains a monument to Pearce’s foresight.

These achievements aside, the decade following the passage of the North-west Irrigation Act was a difficult one for Pearce. Both the climatic and the political environment conspired to undermine his vision. The weather cycle began to shift almost as soon as the act gained royal assent and years of increased annual rainfall eroded farmers’ support for irrigation initiatives. As well, the federal Liberals led by Wilfrid Laurier* came to power in 1896 and Pearce’s influence, along with that of his most senior colleagues in the Department of the Interior, gradually declined. He was demoted to chief inspector of surveys in 1901. Eventually, pressure for his dismissal combined with an attractive offer from CPR president Sir Thomas George Shaughnessy led Pearce to leave government service in 1904 and join the railway team designing the huge Bow River irrigation scheme that he had helped to initiate. He could now focus upon what had long been his priority.

Once the irrigation project was well in hand, the CPR called upon Pearce’s unrivalled knowledge of prairie lands for a new assignment. He was handed the enormous task of doing a demographic and resource survey of all the territory within the railway’s vast land grant while paying particular attention to the millions of acres that remained unsold. Intended as the foundation upon which the railway would plan its spur-line network, this township-by-township survey would take nearly five years to complete and would ultimately help direct the last phase of prairie settlement.

Perhaps in recognition of the immensity of the task ahead, before embarking on the assignment Pearce in 1910 set off on a world tour. Not surprisingly, the focus of his travels was major irrigation projects, including those in Egypt, the Sudan, India, the Philippines, China, Japan, and Australia. The trip, along with his subsequent observation of scores of abandoned homesteads in the dry belt during the course of the CPR survey, reinforced Pearce’s conviction that settlement in much of the prairie region hinged upon irrigation. This view was reflected in the work that he did for the economic and development commission in 1916. The influence of his thinking is apparent in the commission’s recommendation that the federal government study possible comprehensive irrigation schemes for the semi-arid regions in the west. Pearce had just such a scheme to recommend. Impressed by the scale of the irrigation works he had seen in northern India, he envisioned diverting the North Saskatchewan River to irrigate a nearly 20-million-acre region straddling the Alberta–Saskatchewan border. Coinciding with the return of severe drought, Pearce’s scheme gained serious attention. Spurred on by the exodus of settlers from the dry belt, initial topographic surveys demonstrated its feasibility, but the projected cost of $105 million and the return to wet years beginning in 1923 caused momentum to ebb. Pearce remained an advocate, but his voice was lost in the clamour of returning prosperity.

If interest in Pearce’s irrigation ideas dwindled, his stature as the region’s pre-eminent authority on land and resource development remained undiminished, and his advice and involvement were widely sought. He had earlier influenced Alberta’s economic development in another way: as vice-president of the Calgary Petroleum Products Company Limited, he was among the small group of local entrepreneurs responsible for the 1914 Turner Valley oil discovery which ultimately transformed his adopted province.

According to his daughter Adolphina Thornton Tassie, Pearce was “a natural pioneer,” endowed with “fine health and a powerful physique, capable of unlimited endurance.” He was known to his contemporaries as an avid walker and a long-distance snowshoer. He had great intellectual curiosity as well, keeping four encyclopedias in his home. His daughter remembered that he used to tell his children to use a dictionary, sometimes even before they could read. A stalwart of the Church of England in Calgary, he was a member of the Ranchmen’s Club there and of the Manitoba Club in Winnipeg. He kept up his professional ties, as first president of the Alberta Land Surveyors’ Association and a member of the Engineering Institute of Canada, the Association of Professional Engineers of Alberta, and the Corporation of Land Surveyors of the Province of British Columbia. He was also a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and served as vice-president of the Canadian Forestry Association. Interested in urban issues, he was president for a time of Calgary’s City Planning Commission and honorary president of the Alberta Town Planning and Housing Association.

Pearce retired in 1926 but retained an office at the CPR where he continued to work on projects of interest, including a history of the prairie region in which he had played such a prominent part. He died on 3 March 1930 in his beloved Bow Bend Shack, with its irrigated gardens and fine interior woodwork, at the onset of yet another dry cycle. Though he was not physically present to lead the debate, Pearce’s observations, as well as the legislative foundation that he had helped to put in place, would contribute to the framework of discussion for this and each of the droughts that followed. Pearce’s initiatives in the establishment of Canada’s Rocky Mountain forest and park reserves were similarly far-reaching in their impact. Sent west by the Canadian government to help to build a new nation, William Pearce had built carefully and well.

William Pearce is the author of “Detailed report upon all claims to land and right to participate in the North-West half-breed grant by settlers along the South Saskatchewan and vicinity west of range 26, W. 2nd meridian, being the settlements commonly known as St. Louis de Langevin, St. Laurent or Batoche, and Duck Lake,” Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1886, no.8b. He later wrote “Establishment of the national parks in the Rocky and Selkirk mountains: a paper delivered to the Historical Society of Calgary, 16 Dec. 1924,” Calgary Herald, 27 Dec. 1924: 5, also printed in Alberta Hist. Rev. (Calgary), 10 (1962), no.3: 8–27.

AO, RG 80-5-0-98, no.4799. Univ. of Alta Arch. (Edmonton), William Pearce fonds. Assoc. of Ontario Land Surveyors, Annual report (Toronto), 1931: 94–97. D. H. Breen, The Canadian prairie west and the ranching frontier, 1874–1924 (Toronto, 1983). C. S. Burchill, “The origins of Canadian irrigation law,” CHR, 29 (1948): 353–62. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, reports of the Dept. of the Interior, 1880–1905; Statutes, 1894, c.30. S. A. Donaldson, “William Pearce: his vision of trees,” Journal of Garden Hist. (London), 3 (1983): 233–44. D. C. Jones, Empire of dust: settling and abandoning the prairie dry belt (Edmonton, 1987). C. S. Kenny, A treatise on the law of irrigation and water rights . . . (2nd ed., 4v., San Francisco, Calif., 1912), 1. W. F. Lothian, A history of Canada’s national parks (4v., Ottawa, 1976–81), 1. Elwood Mead, Irrigation institutions: a discussion of the economic and legal questions created by the growth of irrigated agriculture in the west (London, 1903). E. A. Mitchner, “William Pearce and federal government activity in western Canada, 1882–1904” (phd thesis, Univ. of Alta, 1971); “William Pearce: father of Alberta irrigation” (ma thesis, Univ. of Alta, 1966). A. A. den Otter, Civilizing the west: the Galts and the development of western Canada (Edmonton, 1982). A. [T. Pearce] Tassie with C. S. Howard, “Prairie surveys and a prairie surveyor,” Canadian Banker (Toronto), 60 (1953), no.2: 53–73.

Cite This Article

PATERSON, JOHN ANDREW, “PEARCE, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pearce_william_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pearce_william_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | PATERSON, JOHN ANDREW |

| Title of Article: | PEARCE, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 18, 2025 |