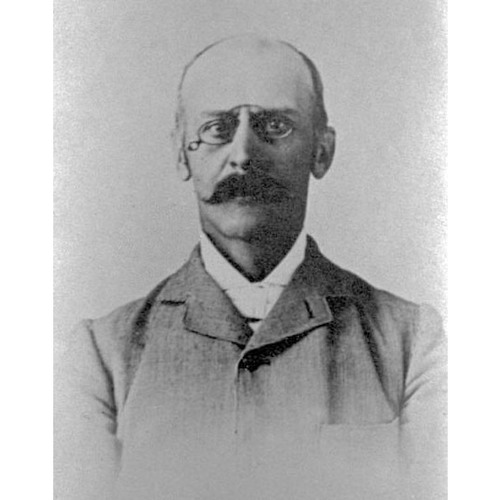

![Description English: James Clinkskill Date 23 May 2011 Source [1] Author unknwon

Original title: Description English: James Clinkskill Date 23 May 2011 Source [1] Author unknwon](/bioimages/w600.7463.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CLINKSKILL, JAMES, businessman, militiaman, politician, university governor, and author; b. 11 May 1840, and baptized 7 June in the parish of East Greenock, Scotland, son of James Clinkskill, an engineer, and Josephine Marie Katrine Michel; m. first 4 April 1884 Dora Babington Taylor in Winnipeg, and they had seven daughters and a son; m. secondly August 1918 Georgina Gibson, née Daunais, in Saskatoon; d. there 6 Aug. 1936.

There is a difference of 13 years between the information recorded about the birthdate of James Clinkskill (and his twin brother, Joseph) in the parochial register of East Greenock, which gives 11 May 1840, and the information of “May 1853” that Clinkskill himself supplied when replying to a questionnaire sent to him by Henry James Morgan*, who compiled various biographical guides on prominent Canadians. It is this spurious date, or occasionally May 1854, that is reported in all published accounts of Clinkskill’s life. Consequently, it is difficult to establish with certainty the chronology of events prior to 1881, when, according to his memoirs, he first considered immigrating to Canada.

Clinkskill said that he had attended Madras College in St Andrews, Scotland, and then began an apprenticeship in the cotton and yarn business, an industry his father had been involved with for many years, at age 17. He left work in textiles to purchase his own grocery-store in Glasgow’s east end. After selling the shop, Clinkskill departed Scotland in early 1882 to look for adventure and more gainful employment in Canada’s North-West Territories. He arrived in Winnipeg in March and, with Thomas E. Mahaffy, he opened a general store in Prince Albert (Sask.) later that year; the next year they moved to Battleford, where commercial prospects seemed better. Clinkskill would finally settle in Saskatoon in 1899.

Clinkskill experienced two major events of territorial days, in one instance as a victim and in the other as an active participant. In his autobiography he gives an eyewitness account of the North-West rebellion [see Louis Riel*] from the vantage point of a Battleford merchant and member of the local Home Guard. The people of Battleford, Clinkskill among them, had taken refuge in the North-West Mounted Police barracks while Indians sacked the village’s buildings. Clinkskill’s home was damaged and robbed, and his store, after being looted, was burned to the ground.

The second major event was the election in 1888 of the territories’ first legislative assembly. Clinkskill, a Conservative, was returned as the member for Battleford, a riding that covered 60,000 square miles. Re-elected in 1891 and 1894, he would conclude ten years of service on 19 Sept. 1898. It was during his first term that he contributed to a significant change in territorial government. In November 1889 Clinkskill, along with Frederick William Gordon Haultain* and other members of the assembly, opposed the advisory council of Robert George Brett* and thus played an essential role in helping to secure full responsible government for the North-West Territories.

Although Clinkskill expressed deep admiration for Haultain, the two men diverged on some issues. Named to the territories’ first Executive Committee in December 1891, Clinkskill resigned the following February because he disagreed with the educational policy of Haultain, then head of the committee. Haultain had introduced a bill challenging the existence of separate schools and instruction in the French language – two items that were central to Clinkskill’s platform [see Alexandre-Antonin Taché*]. Clinkskill, a Presbyterian, had many Roman Catholic constituents and was keen to protect their interests. Though in the past he had publicly expressed opposition to the existence of the dual school system, he had come to realize that he needed Catholic support in order to retain office. In the run-up to the 1891 election he pledged to support separate schools; this promise, however, did not win him a significant number of Catholic votes. The results were different in the 1894 contest. On election day one of his supporters at Onion Lake spread the rumour that the Liberal candidate had made a Catholic swear on a Protestant Bible. Clinkskill offered no objection to the “trick” (as he described it) played on his behalf and, backed by the settlement’s largely Catholic constituency, defeated his opponent.

In 1899 the Clinkskills uprooted themselves from Battleford and left for Saskatoon, with James sitting at the back of the wagon so none of his children would fall off. He moved because the Canadian Pacific Railway had built a line through Saskatoon while the long-promised line to Battleford had never materialized. Clinkskill was taking a chance: by 1901 Saskatoon had only 113 people and he was the first merchant in what would become the city’s downtown. His stone store on 1st Avenue was replaced by a cement building on 21st Street, where the rail station would be built, and he eventually occupied a brick building on 2nd Avenue, Saskatoon’s main thoroughfare. He would retire as a merchant in 1923.

Clinkskill resumed his political career in Saskatoon, serving in the territorial legislature from 1902 until 1905, when the creation of Alberta and Saskatchewan was being debated, and then entering municipal politics. He was mayor in 1906, when Saskatoon incorporated as a city, and again in 1911–12, during which time he oversaw the latter years of a short-lived boom in the city’s development. He ran for mayor once more in 1916, but was defeated. Like other civic leaders, he was involved in business consortiums. A director of the J. C. Drinkle Company, which introduced telephones to Saskatoon, he was also a partner in a cement-block company and a member of a group that planned to dam the Saskatchewan River for power, a proposal that failed. He joined the freemasons, and would become a life member in 1926. Clinkskill was also prominent in service to the community. He was co-founder of the Associated Charities, an organization designed to provide relief to Saskatoon’s poor, and of the Canadian Patriotic Fund; as well he was the prime organizer of the Returned Soldiers’ Welcome and Aid League. Given that his one son, James Thomas, had fought and died in World War I, these two latter organizations would have been of particular importance to Clinkskill.

James Clinkskill’s most enduring contribution to the community, however, was his role in helping to establish the University of Saskatchewan [see Walter Charles Murray*]. In 1907 he had been appointed one of nine university governors entrusted with the task of determining the scope, aim, and location of the future institution. Though a lifelong Conservative, Clinkskill supported a Liberal, Archibald Peter McNab*, in the provincial election of 1908 because of the latter’s promise to bring the new university to Saskatoon or resign. McNab’s pledge was fulfilled, and when it was announced on 8 April 1909 that the university would be coming to Saskatoon, Clinkskill, fellow governor William J. Bell, and McNab were treated as heroes. Writing in his memoirs of the reception the three men received upon returning from Regina, Clinkskill said that “the steam whistles were blowing and bells ringing and the cheers and hurrahs sounded till throats were sore.” Clinkskill’s involvement with the board and executive of the university would continue until 1925.

In 1917 Clinkskill finished his account of his life in the North-West Territories and in Saskatchewan. Carrying the story up to 1912, A prairie memoir presents readers with a detailed personal narrative of the lives and events that shaped the region.

When James Clinkskill died on 6 Aug. 1936, he had outlived almost all of the early builders of Saskatoon. His burial in Woodlawn Cemetery was conducted by his masonic lodge.

James Clinkskill is the author of A prairie memoir: the life and times of James Clinkskill, 1853–1936, ed. S. D. Hanson (Regina, 2003).

NRS, OPR Births & Baptisms, Greenock East (Renfrew), 11 May 1840 (also available online at www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk). Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, 4 March 1932. D. [C.] Kerr and S. [D.] Hanson, Saskatoon: the first half-century (Edmonton, 1982). M. R. Lupul, The Roman Catholic Church and the North-West school question: a study in church–state relations in western Canada, 1875–1905 (Toronto, 1974). L. H. Thomas, The struggle for responsible government in the North-West Territories, 1870–97 (Toronto, 1956).

Cite This Article

Donald Cameron Kerr, “CLINKSKILL, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clinkskill_james_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clinkskill_james_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald Cameron Kerr |

| Title of Article: | CLINKSKILL, JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |