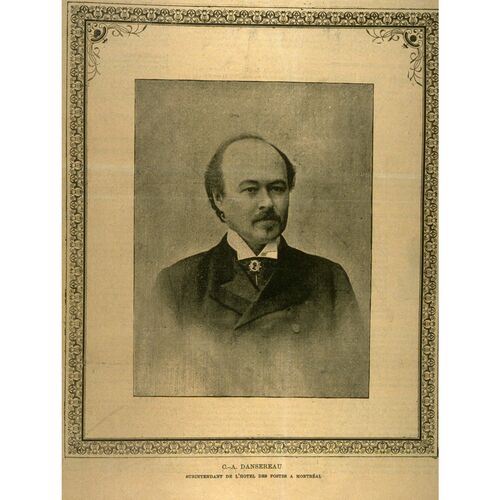

DANSEREAU, ARTHUR (he sometimes signed Clément-Arthur, his baptismal names), newspaperman and office holder; b. 5 July 1844 in Contrecœur, Lower Canada, son of Clément Dansereau and Louise Fiset; m. first 4 Sept. 1866 in Longueuil, Lower Canada, Cordélie Hurteau, youngest daughter of Isidore Hurteau*, a notary, and Françoise Lamarre, and they had two sons and two daughters who survived him; m. secondly 30 Aug. 1880 Stephanie MacKay in Saint-Eustache, Que., and they had one daughter and four sons who survived him; d. 27 March 1918 in Montreal.

Arthur Dansereau was descended from a prominent family in Contrecœur. A well-to-do farmer, his father had done his classical studies at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal and there had become friends with George-Étienne Cartier*, whom he would faithfully support in the riding of Verchères. His mother, who received her schooling at a convent in Saint-Denis on the Richelieu, would devote all the resources of her education, talents, and Christian faith to bringing up her 18 children, 11 of whom would live to an advanced age. When he was eight, Arthur was sent to board with an Irish family so he could learn English, and then with the Clerics of St Viator in Verchères to complete his elementary schooling. From 1855 to 1862 he did his classical studies at the Collège de L’Assomption, where Wilfrid Laurier was a fellow-student. Dansereau was remembered there as a highly gifted pupil and avid reader, enterprising and good natured. During his final two years (the Philosophy program), he wrote Annales historiques du collège de L’Assomption depuis sa fondation, which would be published in 1864 by Eusèbe Senécal*. In the autumn of 1862 he enrolled in the law faculty of McGill College; at Cartier’s suggestion, he articled in the law office of Désiré Girouard, and around 1863 he was also working as a translator at La Minerve (Montréal). He obtained a bcl from McGill in 1865 and was called to the bar on 4 September that year.

Dansereau was not drawn to the practice of law, and still less to parliamentary life, since his natural timidity made him incapable of public harangues, according to one of his biographers. He stayed at La Minerve where, as the talented protégé of Cartier, who gave him the inspiration for his first articles, he moved up to become a journalist and, when Joseph-Alfred-Norbert Provencher* left in 1869, editor-in-chief. Sharing Cartier’s political dream, Dansereau became a champion of Canadian confederation and an advocate of the Liberal-Conservative party. He published forceful articles in favour of the purchase of Rupert’s Land, the construction of a transcontinental railway, and the entry of British Columbia into confederation. In his eyes, the fact that Hong Kong is closer to London via Vancouver and Quebec than by the rival route via San Francisco and New York helped assure the future prosperity of the emerging country. In September 1871 the owners of La Minerve, Louis-Napoléon and Denis Duvernay, finding themselves short of money, sold a part ownership to Dansereau for $8,000, which is believed to have been lent to him by the provincial minister of agriculture and public works, notary Louis Archambeault*, on the security of a mortgage on his father’s land.

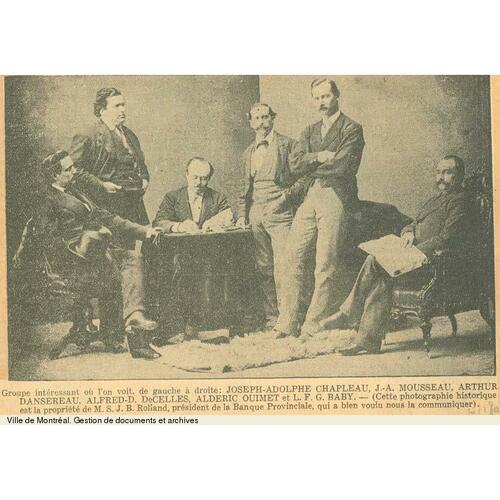

Dansereau typified those sharing Cartier’s viewpoint, centrists as opposed to ultramontanes, and within the Liberal-Conservative party he became a strategist sought out for advice and occasional assistance, as became evident with the Tanneries scandal in 1874, in which he was implicated [see Archambeault; Sir Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*]. Although he supported Hector-Louis Langevin* for the leadership of the party’s Quebec wing after Cartier’s death, he linked his fortunes to those of Langevin’s rival, Chapleau, a friend whom he planned to propel into office. Reputedly it was Dansereau who in 1875 persuaded contractor Louis-Adélard Senécal*, a relative by marriage, to join forces with Chapleau and who urged the latter to distance himself from the ultramontanes and the government of Charles Boucher de Boucherville. He also was believed to have provided Chapleau in March 1878 with the legal and historical arguments for repudiating the so-called coup d’état of Lieutenant Governor Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just. In August 1879 he wrote the Legislative Council’s motion to delay the vote on supply, thereby bringing down the government of Henri-Gustave Joly* and making Chapleau premier of Quebec.

Chapleau relied on a group of close advisers for the conduct of public business. Dansereau, who was said to be the government’s supplier of facts, arguments, and plans, was a sort of minister of the interior without the actual title, of course. He controlled the thinking, the thrust of policies, and political appointments. La Minerve, with its precarious financial situation, was, however, a source of great concern to him. In March 1879, using funds his father-in-law is said to have lent him, he and Jean-Baptiste Rolland* had founded Dansereau et Compagnie, which had bought the Duvernays’ shares in the newspaper. A fortuitous combination of events – the death of his father-in-law followed by that of his wife – obliged him to relinquish La Minerve in order to protect his mother-in-law’s property. Although he remained Chapleau’s adviser, on 3 Aug. 1880 he accepted jointly with Charles Edward Schiller the position of clerk of the crown and of the peace in the district of Montreal in order to earn a living, and early in September he sold La Minerve for $38,000 to some Conservatives sympathetic to Chapleau who were partners in the Compagnie d’Imprimerie de La Minerve [see Joseph Tassé*]. In July 1882 he was replaced as clerk after he gave up the office because its duties were incompatible with his political activities. The government of Joseph-Alfred Mousseau* sent him to Europe in the autumn of 1883 to buy books for the Legislative Library, which had been destroyed in a fire in April that year. The relevance of the volumes he purchased and of the invoices he produced would be the subject of along debate in the house in the spring of 1886. The opposition would accuse him of submitting duplicate invoices and misusing the 75,000 francs (about $15,000) placed at his disposal. In the end, the government would use its majority in the house to silence the opposition and the matter was dropped.

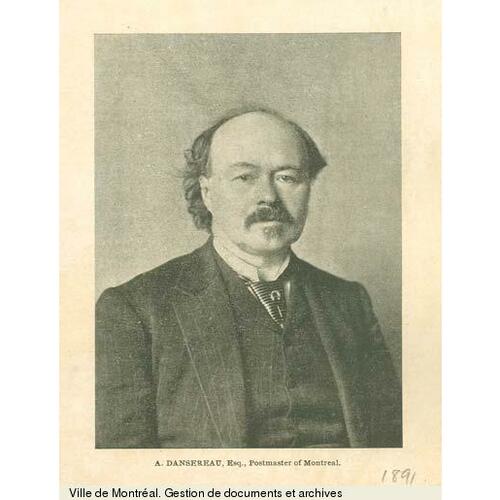

On his return from Europe in 1884, Dansereau found that Chapleau’s supporters were losing momentum. Their leader had chosen to serve at the federal level, where Langevin kept him in a minor post, while at Quebec John Jones Ross* headed a cabinet that included a strong ultramontane element. Something had to be done. In October 1884 Senécal’s son-in-law, William Blumhart, launched La Presse, a newspaper that wholeheartedly backed Chapleau, and Dansereau became editor-in-chief. It was all in vain. Chapleau’s fate was linked to that of the Quebec wing of the Liberal-Conservative party; shaken by the turmoil over the hanging of Louis Riel*, the defection of the ultramontanes, and the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway*], it was in the throes of fratricidal strife. Laurier, the leader of the Liberal party, was well on the way to replacing Chapleau in the hearts of the voters. The time had come to abandon ship. In January 1891 Dansereau was appointed postmaster in Montreal, and the following year Chapleau accepted the lieutenant-governership of Quebec.

Dansereau did not give up journalism and politics, however. In 1894 he began writing a science column for La Presse, and he invited both Bleus and Rouges to his home in Longue-Pointe (Montreal) to prepare for a realignment of political forces. On both sides consideration was being given to a union at the provincial level of moderates from both major parties so that both ultramontanes and radicals could be pushed aside. Under pressure from Liberal activists, Laurier, who had been elected prime minister in 1896, rejected this plan. Chapleau had to retire from active political life in 1897 and Dansereau, under the patronage system of the time, had to submit his resignation as postmaster in February 1899. On 27 March he became the political editor of La Presse, where his mission was to defend Laurier’s policies. He would hold this position for the rest of his life. Under his direction, La Presse shifted in less than two years from benevolent neutrality towards Laurier to unswerving editorial support. Dansereau’s position called for a high level of tact. La Presse was no longer a journal of opinion, but a commercial enterprise whose profitability depended on providing general information to a broad readership. It was part of the editor’s responsibility to see that the paper, while backing Laurier editorially, did not antagonize advertisers, the clergy, interest groups, or voters. Dansereau, as Laurier’s adviser and publicity man, but also the confidant of Trefflé Berthiaume, the owner, would always excel at this task.

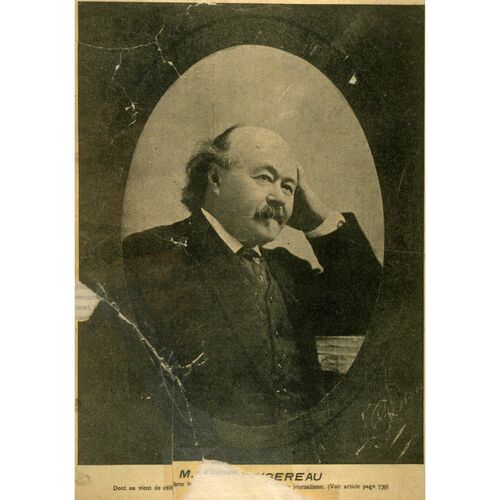

What made Dansereau’s career unique was not only his longevity, but also his sudden comebacks and his panache. Physically, despite a plain appearance and timid ways, he cut an impressive figure, with his athlete’s chest, broad forehead, and face resembling Honoré de Balzac’s. Gentle and calm by nature, extremely sensitive, and generous to the point of prodigality, he had the sentiments and tastes of a grand seigneur. His superior mind was served by an encyclopaedic memory, a vast erudition, an intelligence capable of developing broad concepts and weighing the pros and cons of a proposal, an intuitive sense of what was in the wind, and sound judgement in assessing men and situations. A man of action enamoured of power, he faithfully served two men in turn, one Bleu, the other Rouge, because both Chapleau and Laurier had, at different times, carried on the tradition of Cartier, his mentor. In 1907, at the banquet marking his 40 years as a journalist, he confessed that Cartier “gave me a rule of life from which I have never deviated.” This rule was a political vision that saw no future for the French Canadian nation except within a confederation of colonies inspired by deep loyalty to the British crown and by fraternity between the two peoples, which did not exclude a healthy rivalry in business and politics. Despite his partisan stands and sudden about-faces, Dansereau had constantly defended this vision in articles that were always closely reasoned, usually well documented, sometimes marked by a definite nobility of thought. As one privileged to witness the metamorphosis of newspapers, he came to assign the press a lofty mission in shaping public opinion. “It is to an independent and unfettered press, even more than to the bench, the bar, and the pulpit, that the people owe their protection against oppression and injustice.”

Arthur Dansereau has been identified as the author of the following pamphlets: Les Rouges et les Bleus devant le pays: quelques pages de politique (Montréal, 1875); Le lieutenant-gouverneur de Québec et les prerogatives royales (Montréal, 1878); Les ruines libérales (Montréal, 1878); Cantate: les cygnes malades (Montréal, 1879); La crise politique de Québec: notes et précédents (Québec, 1879); Protection et libre-échange, quelques statistiques (Montréal, 1879); Le refus des subsides: autorités et précédents (Montréal, 1879); and Les contes de M. Mercier ([Montréal?, 1883?]). He also published a sketch of Sir Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau in Men of the day: a Canadian portrait gallery, ed. L.-H. Taché (32 ser. in 16v., Montréal, 1890–[94]), 4th ser. (translated by John Francis Waters), and one of Sir George-Étienne Cartier in George-Étienne Cartier: études (Montréal, [1914?]).

ANQ-M, CE1-12, 4 sept. 1866; CE1-58, 6 juill. 1844; CE6-11, 30 août 1880. Arch. de l’Univ. du Québec à Montréal, Fonds Clément-Arthur-Dansereau. Arch. de l’Univ. Laval (Québec), P293 (fonds Elzéar-Lavoie). NA, MG 26, G. Gazette (Montréal), 28 March 1918. La Minerve, 22 août 1864. Le Monde illustré (Montréal), 14 févr. 1891. Montreal Daily Star, 3 Feb. 1899, 27 March 1918. La Patrie, 4 janv. 1915, 27 mars 1918, 23 avril 1944. La Presse, 27 mars 1899; 19 juill., 22 août 1902; 9 sept. 1907; 27, 30 mars, 22 juin 1918. Jean Armand, “Clément-Arthur Dansereau (de La Presse) et la Guerre 1914–1918: exploration d’un corpus documentaire et des éditoriaux” (mémoire de ma, univ. Laval, 1989). F.-J. Audet, Contrecœur; famille, seigneurie, paroisse, village (Montréal, 1940). F.-M. Bibaud, Le panthéon canadien; choix de biographies, Adèle et Victoria Bibaud, édit. (nouv. éd., Montréal, 1891). Jean de Bonville, “Les dossiers de presse d’Arthur Dansereau: description et évaluation de la documentation” (mémoire, École de bibliothéconomie, univ. de Montréal, 1975); La presse québécoise de 1884 à 1914; genèse d’un média de masse (Québec, 1988). Cyrille Felteau, Histoire de “La Presse” (2v., Montréal, 1983–84). Anastase Forget, Histoire du collège de L’Assomption; 1833 – un siècle – 1933 (Montréal, [1933]). J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise, vols.2–3. “The Quebec political crisis” (notes and precedents): the opposition pamphlet, better known as the “Dansereau brochure,” examined and refuted by the light of British constitutional history and precedent (Quebec, 1879). Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.1–14, 20, 22. Lise Saint-Jacques, “Mgr Bruchési et le contrôle des paroles divergentes: journalisme, polémiques et censure (1896–1910)” (mémoire de ma, univ. du Québec à Montréal, 1987). Vieux-Rouge [P.-A.-J. Voyer], Les contemporains: série de biographies des hommes du jour (2v., Montréal, 1898–99), 1: 17–25.

Cite This Article

Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin, “DANSEREAU, ARTHUR (Clément-Arthur),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dansereau_arthur_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dansereau_arthur_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | DANSEREAU, ARTHUR (Clément-Arthur) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |

![M. Arthur Dansereau [image fixe] Original title: M. Arthur Dansereau [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.6666.jpg)