Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

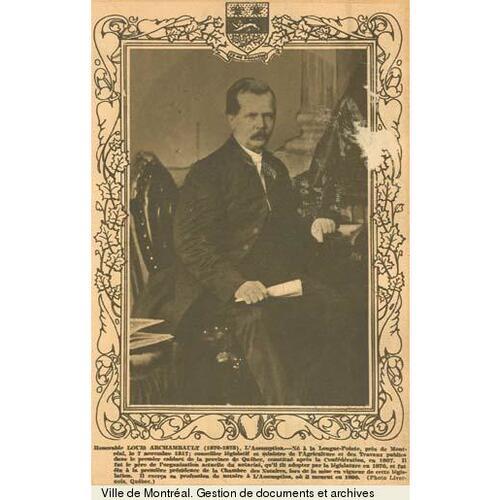

ARCHAMBEAULT (Archambault), LOUIS, notary and politician; b. 7 Nov. 1814 at Longue-Pointe (Montreal), Lower Canada, son of Jacques Archambault, a farmer, and Catherine Raimondvert; m. first 9 Aug. 1839 Éloïse (Élise) Roy, at Saint-Roch-de-l’Achigan; m. secondly 17 July 1848 Marguerite-Élisabeth Dugal, at Terrebonne, and their children included Horace*, politician and judge, and Joseph-Alfred*, first bishop of Joliette; d. 2 March 1890 at L’Assomption, Que.

Louis Archambeault, who had only a primary education, was commissioned as a notary in 1836, and went into practice at Saint-Roch-de-l’Achigan, where he became mayor. On 18 March 1843 he was appointed registrar of Leinster County, divided in 1853 into L’Assomption and Montcalm. He was a warden of Leinster from 1848 and was re-elected by acclamation in L’Assomption County in September 1854 for a year, as he was again in 1877. In 1855 he left Saint-Roch-de-l’Achigan for the village of L’Assomption, where he was to be mayor from 1877 to 1882.

He took an intense interest in the question of the abolition of seigneurial tenure, and campaigned actively in the “anti-seigneurial convention of the district of Montreal.” In 1853 this body adopted a plan for abolition, but Archambeault opposed the proposal because it involved redemption of seigneurial dues by the government. Archambeault asserted that “he considered it neither just nor equitable that public funds should be used to reimburse the censitaires to the detriment of workers in the city and the habitants of the Eastern Townships, who are not involved in the question and who also pay their quota into the public coffers.” He put forward an alternative, which Le Canadien (Quebec City) considered preferable to the convention’s proposal “as a plan for an immediate and general commutation.” His participation in the debate earned him a reputation for competence; hence on 3 March 1855 he was appointed one of ten seigneurial commissioners to compile a land register.

In 1855 Rouge mla Joseph Papin* accused him of having inadequately discharged his responsibility as a returning officer in the 1851 and 1854 elections. An inquiry in fact established that Archambeault had padded his accounts and improperly drawn a sum of about £150. Although this was a common practice at the time, he was relieved of his duties as registrar and seigneurial commissioner in January 1856; shortly after, he resigned as lieutenant-colonel in the militia. In the 1858 election Archambeault satisfied his desire for revenge by running against Papin, who was at a disadvantage because of the stand he had taken on denominational schools. To the surprise of most people, Archambeault defeated Papin by 18 votes. In 1861, however, over-confidence and poor organization led to his defeat by Alexandre Archambault, brother of Pierre-Urgel*. Since religious teaching in schools and Louis Archambeault’s integrity were issues debated in the two elections, it seems possible that the voters had changed their minds about both matters. As compensation George-Étienne Cartier* reinstated him on 1 Feb. 1862 as lieutenant-colonel in the militia but on 6 September, after the Liberals had come to power, Archambeault was again relieved of his appointment. From this time election contests in L’Assomption became a kind of clan rivalry or feud between two families: according to La Minerve (Montreal), in the 1863 elections Louis Archambeault not only had to face the mla who was outgoing but also “All the Archambaults, brothers, nephews, cousins of the great Alexandre . . . [who were] campaigning.” Le Pays of Montreal contended that Archambeault regained his seat with the help of clerical intervention.

Louis Archambeault showed no enthusiasm for the Quebec resolutions in 1865. He thought they set out “a system closer to legislative than to federative union.” But Cartier overcame his friend’s reservations. On 15 July 1867 Archambeault was made commissioner of agriculture and public works in the government of Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau in the new province of Quebec. From 2 Nov. 1867 he represented the division of Repentigny in the Legislative Council. The Conservative press approved, but Le Pays was shocked at the choice of a “legally convicted thief,” of an “extortioner condemned by the highest authority in the country.”

On the whole Archambeault proved an excellent minister. He was active in all of the many areas in his department, one of the most important in the Quebec government. With the help of assistant commissioner Siméon Le Sage* he made organizational changes, replacing the Board of Agriculture by an agricultural council controlled more closely by the executive. He protected the schools of agriculture of Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (La Pocatière) [see François Pilote] and L’Assomption (which he had helped to found [see Pierre-Urgel Archambault]), against those who were pressing for a single school.

Increasing emigration to the United States was profoundly disturbing to the national conscience. Politicians turned to the only available solution – the settlement of new lands. Archambeault’s work in this area is even more worthy of note than his work in agriculture. The laws which his efforts led to were to remain in force until the end of the century. Government financial assistance to settlement was greater between 1869 and 1873 than at any other time until 1900 except under the ministries of John Jones Ross* and Honoré Mercier*. To maintain the demographic balance within the Canadian federation, he sought to attract French-speaking immigrants, particularly rural people who were “moral and law-abiding,” and had little money saved; never has Quebec taken as much initiative in this sphere as it did during the early 1870s. The sums voted at that time were double what they would be in 1880–81, and five times as much as in 1898–99.

Beyond serving as legislative councillor and minister, Archambeault also ran in the federal elections of 1867, defeating Pierre-Urgel Archambault by 233 votes. After the double mandate was abolished by federal law, Archambeault resigned from the House of Commons on 2 Jan. 1874 and did not run in the 1874 elections. In that year he was implicated in the Tanneries scandal, which brought about the fall of the Gédéon Ouimet* cabinet and left him with only the role of legislative councillor; he returned to practise as a notary. The Tanneries scandal, an episode in the lane speculation fever raging in the Montreal region during the 1870s, was caused by the government’s exchange of a plot of land for a less valuable one whose price had been artificially inflated. Speculators were thought to have shared part of the profit with their political associates. Archambeault persistently declared his innocence, but even the most sympathetic observer cannot avoid feeling uneasy. As commissioner of public works in the Ouimet government he was primarily responsible for the exchange. He did not manage to explain convincingly the famous $50,000 deposited in his name. His personal integrity was not, however, in question; the suspicion was that the transaction was designed to ensure the financial future of La Minerve and replenish the party’s coffers. Archambeault disapproved of Ouimet’s resignation, prompted by the departure of the three English-speaking members of his cabinet, and asserted: “I would have tried to fill the gaps [left by the ministers who resigned]. . . . On the supposition that no Englishman would want to enter the government, I would have called upon Canadiens instead. . . . This vigorous approach would have made these Englishmen reconsider, and would ultimately have brought them round to us.” Like Ouimet he uncovered “odious plots, traitors, villains” at the bottom of the affair. One name in particular emerged, that of the former attorney general, George Irvine*, who had been the first to resign. In spite of his experience could Archambeault have been as much victim as accomplice?

Be that as it may, he did not re-examine his political allegiance. Circumstances and differences of opinion nevertheless did change his thinking. In the first place he was opposed to a new plan for the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway, which the cabinet of Charles Boucher* de Boucherville advocated (that is, to abandon the Bout-de-l’Île line through L’Assomption for another passing through Terrebonne). After the 1878 coup d’état [see Luc Letellier de Saint-Just] Premier Henri-Gustave Joly* offered Archambeault a portfolio but he declined and remained in the Legislative Council, voting “for the ministerial proposals that appeared sound and worth adopting.” He was in favour of the Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau* ministry at first but attacked it vehemently over the sale of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway to Louis-Adélard Senécal and the Canadian Pacific syndicate. The Louis Riel affair was the cause of the final stage in his evolution: he became a “National” Conservative, shoulder to shoulder with his former enemies, Liberals and Ultramontanes, in the same political movement. On 6 June 1888 he gave up his seat on the Legislative Council in favour of his son Horace, whom the press also labelled a National Conservative. Horace eventually completed the evolution in political allegiance begun by his father by becoming a Liberal minister; but when Louis left public life, L’Étendard of Montreal wrote that he had “always been an out-and-out Conservative.”

Archambeault made a lasting name for himself not only in political history but also in the notarial profession. A member of the Montreal Board of Notaries from 1848 on, he sat on its executive from 1859 and was its president from 1865 to 1870. He held the same position on the Provincial Board of Notaries (1870–76). In both law and agriculture, Archambeault was a reformer. He was responsible in 1870 for the law which, chiefly through the creation of the single board, helped to raise the notarial profession from the depths to which it had sunk [see Louis-Édouard Glackmeyer].

His career, fruitful but chequered, was overshadowed by the scandals of 1856 and 1874. Firm, energetic, and aggressive, he was one of the strong men of the Chauveau and Ouimet cabinets. According to an anonymous biographer, “his knowledge of constitutional law and his talents as an administrator should have ensured him a place in the cabinet even before confederation. His difficulty in handling the English language always led him to refuse offers made to him on various occasions.” Had he mastered it, he could have asserted his claim to succeed Cartier, in preference to Hector-Louis Langevin*, a brilliant subordinate but a mediocre leader.

[No Louis Archambeault papers exist but various repositories hold separate items. Some of Archambeault’s official correspondence is at ANQ-Q, in the public works records (PQ, TP) for the years 1867–74. This material includes a few of Archambeault’s letters to officials in his department written in the course of his numerous absences; after having dealt with current concerns, he occasionally added personal comments on the politics of the day. The Siméon Le Sage papers (AP-G-149) contain one letter from Archambeault to Le Sage and several from the latter to him. At PAC, the Gédéon Ouimet papers (MG 27, I, F8, 1–2) in particular should be consulted for the Tanneries affair. There are also one or two items in the papers of John A. Macdonald (MG 26, A), George-Étienne Cartier (MG 27, I, D4), and Francis-Joseph Audet* (MG 30, D1). The Joseph-Israël Tarte* papers (MG 27, II, D16), contain a lengthy and interesting letter on the confederation scheme written by Archambeault to Joseph-Guillaume Barthe*. ASQ holds a letter from Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau to Hospice-Anthelme-Jean-Baptiste Verreau* which mentions Archambeault (Fonds Viger-Verreau, carton 96: no. 105). The collection Baby (P 58, U) at AUM has two of Archambeault’s letters. For his militia career, see PAC, RG 9, I, C4; C5; and C6. p.t. and l.t.]

AC, Joliette, État civil, Catholiques, Saint-Roch-del’Achigan, 9 août 1839; Terrebonne (Saint-Jérôme), État civil, Catholiques, Saint-Louis (Terrebonne), 17 juill. 1848. ANQ-M, État civil, Catholiques, Saint-François-d’Assise (Montréal), 7 nov. 1814. Can., prov. du, Assemblée législative, App. des journaux, 1854–55, VIII: app.N; 1857, VII: app.43: VIII: app.51; Parl., Doc. de la session, 1862, IV: no.24; févr.–mai 1863, V: no.29. Documents relatifs à l’échange des propriétés des Tanneries, près de Montréal (n.p., n.d.). Qué., Commission royale, Enquête concernant le chemin de fer de Québec, Montréal, Ottawa et Occidental (4v., Québec, 1887), III: 78–90. Achintre, Manuel électoral. Biographie de l’hon. Louis Archambeault, ministre de l’agriculture et commissaire des T. P. pour Québec, conseiller législatif et membre des Communes (n.p., 1873). Anastase Forget, Histoire du collège de L’Assomption; 1833 – un siècle – 1933 (Montréal, [1933]). M. Hamelin, Premières années du parlementarisme québécois. Christian Roy, Histoire de L’Assomption (L’Assomption, Qué., 1967), 321–22, 441–42, 462–63, 498. J.-E. Roy, Hist. du notariat, II: 548; III: 240, 247, 292–93, 321, 330–483; IV: 1–32, 71–75, 100, 121, 178–94, 269–71, 357–59, 426–40. J.-J. Lefebvre, “Les Archambault au Conseil législatif; quelques précisions sur sir Horace, l’hon. Louis et l’hon. Pierre-Urgel Archambault,” BRH, 59 (1953): 23–28.

Revisions based on:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. du Vieux-Montréal, CE605-S14, 5 mars 1890.

Cite This Article

Pierre and Lise Trépanier, “ARCHAMBEAULT (Archambault), LOUIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/archambeault_louis_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/archambeault_louis_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre and Lise Trépanier |

| Title of Article: | ARCHAMBEAULT (Archambault), LOUIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |