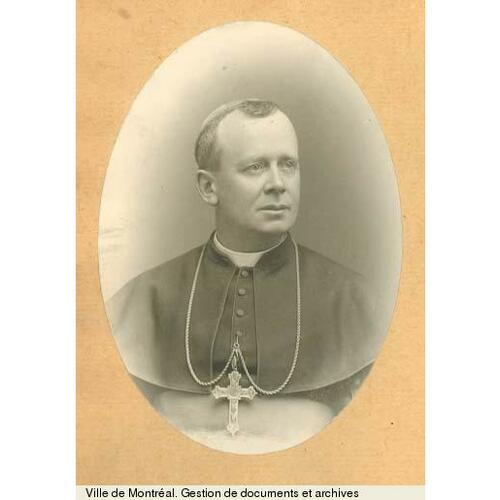

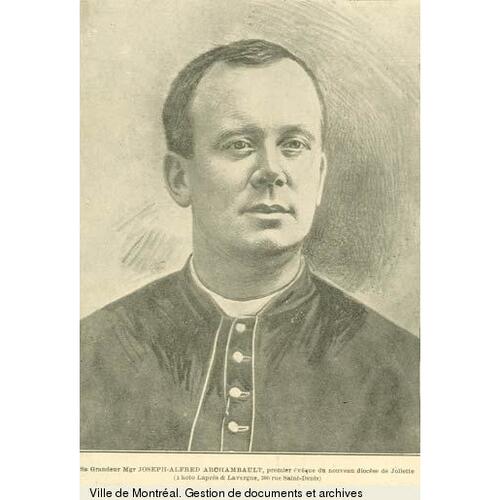

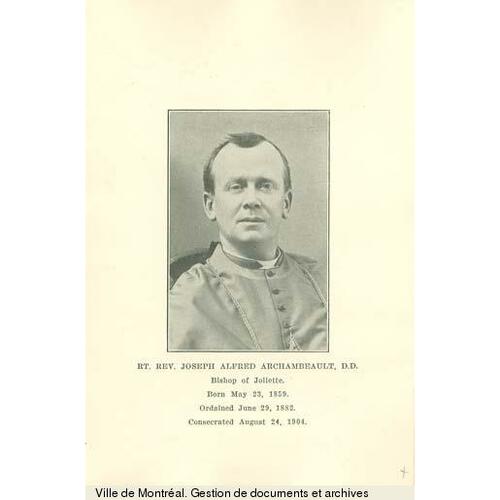

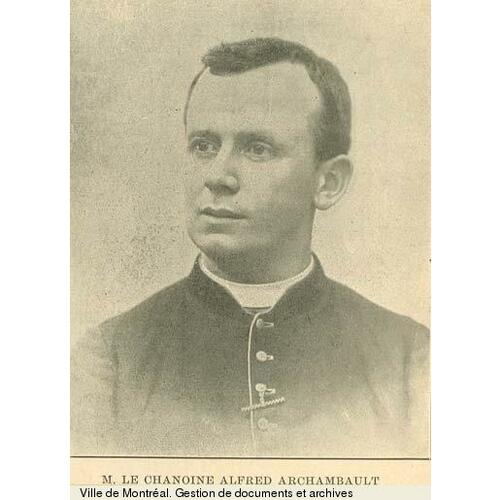

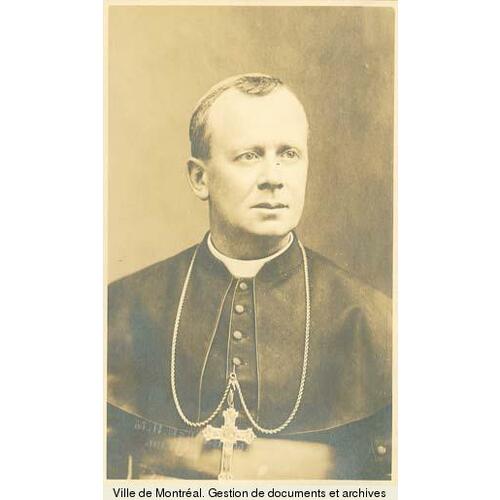

ARCHAMBEAULT, JOSEPH-ALFRED (baptized Joseph-Hector-Alfred, he signed Alfred until 1904), Roman Catholic priest, educator, church and school administrator, and bishop; b. 23 May 1859 in L’Assomption, Lower Canada, son of Louis Archambeault*, a notary and politician, and Marguerite-Élisabeth Dugal; brother of Sir Horace Archambeault; d. 25 April 1913 in Saint-Thomas, near Joliette, Que.

Joseph-Alfred Archambeault did his classical studies at the Collège de L’Assomption from 1870 to 1877 and his theological training at the Grand Séminaire de Montréal. After being ordained priest in 1882 by Bishop Édouard-Charles Fabre*, he left for three years of further education in Rome, where he obtained doctorates in theology and in canon law. During this period he made a great many European friends, whom he would visit regularly.

From 1885 to 1888 Archambeault taught philosophy at the Collège de L’Assomption. While there, he and a few colleagues drafted a memorandum proposing L’Assomption as the seat of the diocese to be erected in the district of Joliette. In 1888 Fabre, who by now was an archbishop, brought him to Montreal to be his vice-chancellor; he became chancellor in 1892. With his methodical mind, Archambeault expedited matters “in an orderly fashion and on time,” occasionally at the risk of irritating people. He won Fabre’s complete confidence by his advice on such difficult issues as the condemnation of Canada-Revue (Montréal) in 1892. According to his archbishop, Archambeault’s exposition of church doctrine during the civil suit helped obtain a judgement favourable to the religious authorities [see Aristide Filiatreault]. It was by virtue of this confidence that he accompanied Fabre to Rome in 1890 and represented him there in 1896. One of the matters he discussed with the cardinals and the pope himself was the difficult question of Manitoba’s schools [see Thomas Greenway*].

In Montreal, in addition to serving as chancellor, Archambeault was ecclesiastical superior to the Sisters of Charity of Providence from 1891 to 1904, and in 1900 he supervised the writing and approval of their rules and constitutions. In 1888 he had begun teaching natural law in the faculty of arts at the Université Laval in Montreal, of which he was vice-rector from 1902 to 1904. Made a canon in 1891, he was appointed protonotary apostolic in 1902.

Anxious to preserve “the traditions of complete submission and absolute obedience to the Church of Rome,” in December 1896 Fabre designated Canon Archambeault as his successor. When Fabre’s bishops met on 4 Jan. 1897, however, they quickly and “unanimously” ruled him out because of his “extremely brusque and fiery” personality and because of his youthful appearance. But as the obstacles to the erection of a diocese in Joliette fell away in the years from 1900 to 1903, Archambeault was the one most frequently proposed for the office of bishop. Rome announced his appointment on 27 June 1904 and his episcopal ordination took place in Joliette on 24 August.

Since the new diocese already possessed the essential resources, Bishop Archambeault used his brief tenure – less than nine years – to improve what was there and to make innovations in certain areas. In 1905 he restored the parish church of Saint-Charles-Borromée in Joliette, which had now become a cathedral, and he would continue to embellish it with, among other things, windows paid for by public subscription. Contemporaries praised the beauty of the liturgical ceremonies over which he presided there. Archambeault took a special interest in education. Thus, from the beginning of his episcopate, he required those entering the priesthood to spend three years studying theology at the Grand Séminaire de Montréal and sent many young priests to Rome for further education. He made the Collège Joliette, which was run by the Clerics of St Viator but had some secular clergy on its teaching staff, into his diocesan minor seminary and helped it develop. Archambeault’s interest in elementary education was equally evident. He completed a network of schools or academies and convents run by teaching brothers and by nuns. To raise the educational level of women teachers, he insisted on establishing a board of examiners in Joliette and opening a normal school for girls in 1912. Every year he visited a number of schools and convents. In a report written in 1909 he boasted that school attendance was higher in his district than anywhere else in Quebec.

In the field of social welfare Bishop Archambeault was equally active. He encouraged the expansion of the Hôpital Saint-Eusèbe in Joliette, and the opening of an orphanage for boys, a kindergarten in Joliette, and an old men’s home in Laurentides. In 1909 the diocese had a hospital, five homes for the aged, and five orphanages for girls and one for boys, assisted by a branch of the Society of St Vincent de Paul and six women’s charitable associations.

Archambeault attacked the “scourge of intemperance,” in particular by publishing his pastoral letter of 24 June 1906, which met with great success. A year later he was in a position to tell François Langelier, president of the Ligue Antialcoolique de Québec: “In the diocese of Joliette, the Société de Tempérance is currently set up in all the parishes. The number of hotels has decreased significantly. The sale of intoxicating beverages has been reduced to one-third of what it was formerly.” He regularly reminded his priests, however, that the struggle is never over, and he himself frequently issued both congratulations and warnings to the local governments, which were the guardians of the law.

The bishop also called the municipal authorities to task – especially those in Joliette – on the subject of the recreation available to the public. In 1909, for example, he complained to the mayor and aldermen about the Cinémato, which put up “immoral” posters advertising dangerous plays. If this program was not withdrawn, he threatened to forbid “all Catholics to attend these performances [so] apt to destroy innocence and corrupt morals.” He kept an equally close watch on “Moving picture shows, now accompanied by recitations, singing, dancing, etc.” In the same year he also attacked the Joliettoscope; it had, he claimed, “more than once shown moving pictures suggestive of things contrary to morality, scenes regrettable from the point of view of the respect due to ministers of religion,” and it “even went so far as to utter an odious mockery of God’s omnipotence in the world.” He asked the municipal council to take “really effective measures” to make the two cinemas respect religious faith and morality.

His defence of orthodoxy brought him into a long debate with Dr Albert Laurendeau of Saint-Gabriel-de-Brandon on the subject of evolution and transformism. There in 1911 the physician published his arguments in a volume entitled La vie: considérations biologiques, and Archambeault condemned it solemnly on 19 March 1912 in a circular to be read in all parish churches and public chapels. In 1910 the bishop had given four instructions about secret societies and condemned the freemasons. When he learned that 13 people of his diocese belonged to the Cœurs Unis Lodge No.45, he immediately reprimanded them and called on them to recant. Only one refused, and he was excommunicated.

As a specialist in canon law, Archambeault played a very active role in the first plenary council of Canadian prelates, held at Quebec from 19 Sept. to 1 Nov. 1909. Appointed secretary of the congregatio (assembly) of bishops, he wrote the minutes for a number of sessions and helped draft the collective pastoral letter and publish the council’s proceedings, all of which kept him occupied for several months after the event. At the same time he took advantage of the International Eucharistic Congress held in Montreal in 1910 to publish a long, three-part pastoral letter about the Eucharist.

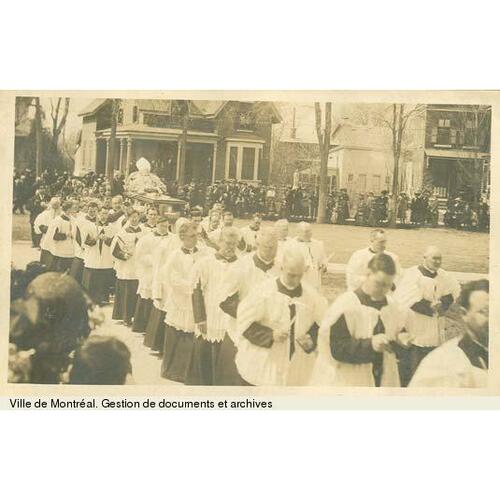

These latter efforts undermined Archambeault’s health and he remarked more frequently that he was “running out of strength.” He planned on travelling to Rome in 1911 for a rest, but had to postpone the visit until the following year. He left Joliette on 15 Aug. 1912 and returned on 28 Jan. 1913, after attending the Eucharistic congress in Vienna, making his ad limina visit to Rome (two years ahead of schedule), and meeting his friends from Rome and France. However, the journey did not bring him the rest he had counted on, and three months after his return he died suddenly during a visit to the presbytery at Saint-Thomas. The tributes elicited by his sudden demise (he was only 53) reveal the image of him that the people of his diocese would recall: an intellectual of the highest order, a fervent pastor, a man of discipline and doctrine, and a gentle and likeable figure.

Joseph-Alfred Archambeault published three pamphlets: Sermon donné à L’Assomption, le 14 juin 1893, à l’occasion des noces d’or sacerdotales de M. l’abbé P. F. Dorval (Montréal, 1893); Sermon sur l’autorité des évêques, donné le 1er mai 1894 dans la cathédrale de Montréal . . . (Montréal, 1894); and L’autorité sociale, sa nature, sa nécessité, son origine, son exercice; conférence faite à la basilique de Québec (Québec, 1909). His thinking and his pastoral directives appear in Lettres pastorales, mandements et circulaires (14v. parus, Joliette, Qué., 1908– ), vols.1–3. Bishop Archambeault’s papers are preserved in the Arch. de l’Évêché de Joliette, in particular congratulatory letters and his travel diaries. Other useful sources in the archives include the Reg. des lettres, 1 (1904–11) and 2 (1911–13) and the Reg. des lettres particulières, 3 (1907–15), as well as “Quelques notes historiques sur l’épiscopat de Mgr Archambeault” and Yvan Melançon, “Mgr J.-A. Archambault et sa deuxième visite ‘ad limina’” (texte dactylographié, s.l., 1984).

ANQ-M, CE5-14, 25 mai 1859. Archivio della Propaganda Fide (Rome), Acta, vol.268; Nuova serie, vol.121.

Cite This Article

Nive Voisine, “ARCHAMBEAULT, JOSEPH-ALFRED (baptized Joseph-Hector-Alfred) (Alfred),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/archambeault_joseph_alfred_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/archambeault_joseph_alfred_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Nive Voisine |

| Title of Article: | ARCHAMBEAULT, JOSEPH-ALFRED (baptized Joseph-Hector-Alfred) (Alfred) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |