Source: Link

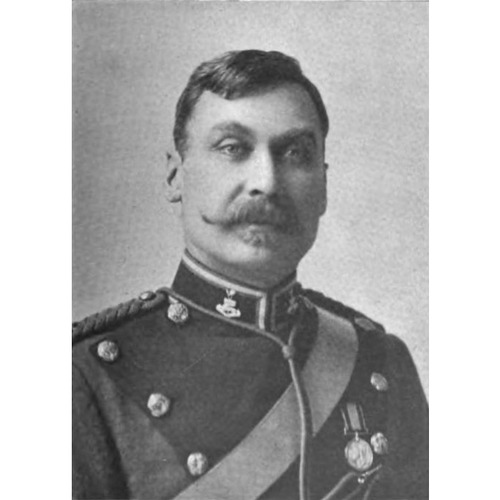

LEONARD, REUBEN WELLS, engineer, militia officer, mining magnate, civil servant, and philanthropist; b. 21 Feb. 1860 in Brantford, Upper Canada, son of Francis Henry Leonard, a businessman and civic official, and Mary Elizabeth Catton; m. 11 Oct. 1889 Kate Rowlands (d. 12 Sept. 1935), granddaughter of James Lesslie*, in Kingston, Ont.; d. 17 Dec. 1930 in St Catharines, Ont.

Reuben W. Leonard attended Brantford Collegiate Institute, and following a short stint as a teacher in Brant County he entered the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston to study civil engineering. He graduated in 1883 as the bronze medallist in a class of 23 cadets, and for the next two years worked as an engineer for the Canadian Pacific Railway (leaving temporarily to serve in the militia during the North-West rebellion of 1885 [see Louis Riel*]). His engineering career then took off. In the period from 1886 to early 1906 he was involved mainly in railway and hydroelectric projects in central and eastern Canada. Among these, his crowning achievement was the construction of the first Niagara Falls power station, in 1892–93.

In 1905 Leonard’s life would take a dramatic turn. A grubstaking venture in northern Ontario led that year to the acquisition of a mineral-rich claim in the centre of Cobalt. These mines contained cobalt (co), nickel (ni), silver (ag), and arsenic (as) and so the business was named Coniagas Mines Limited; Leonard served as its president and general manager. In 1908 he established and became president of the Coniagas Reduction Company Limited in Thorold, where the ores were processed. In nearby St Catharines, Leonard and his wife built a stately home, Springbank, which overlooked the old Welland Canal. The Leonards had no children, but a nephew, Arthur Leonard Bishop*, came from Brantford to St Catharines to attend school; he became their ward, and later heir to the Leonard fortune.

Leonard was a successful businessman and a renowned philanthropist, giving extensively to educational institutions, churches (low-church Anglican), hospitals, and other causes. It became lore that he viewed his great wealth as a public trust. Leonard was appointed to boards of governance at the University of Toronto, Wycliffe College in Toronto, Ridley College in St Catharines, the School of Mining and Agriculture and Queen’s University in Kingston, and the Khaki University of Canada. Keenly interested in imperial politics, he served on the Canadian executive of the Round Table, a study group devoted to the reorganization of the British empire. Kate Leonard was similarly active, prominent in such institutions as the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, the Victorian Order of Nurses, and the Young Women’s Christian Association.

In 1911 Leonard was appointed by Prime Minister Robert Laird Borden* to succeed Simon-Napoléon Parent* as chairman of the Transcontinental Railway Commission, where he spent three years diligently overseeing the construction of the line from Moncton, N.B., to Winnipeg. When the war broke out Leonard committed himself to aiding the cause: not content to stay safely at home, he spent several months in Europe in 1915; as a major in the Corps of Guides – he had joined in 1904 and would become a lieutenant-colonel in September 1915 – he monitored anti-British sentiment in the United States; as an executive of the Win-the-War movement, he lobbied for the formation of the Union government in 1917. He gave generously to support the war effort and helped to raise funds through such agencies as the Canadian Patriotic Fund.

Following the armistice Leonard continued with an array of philanthropic activities. He served a year as president of the Engineering Institute of Canada in 1919–20 and was appointed in 1920 to the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission. However, he rejected an invitation to join the League of Nations Society in Canada. The League was doomed to fail, he argued, because it did not acknowledge the vast and ineradicable differences that existed among races. Coniagas also demanded his attention. The price of silver, the main ore, began to recover after the war. In 1919 a bitter strike halted production for seven weeks, as Leonard and the other mine owners in the Cobalt region successfully prevented the unionization of the miners. Leonard’s disdain for unions was manifested not only at Coniagas, but also at the University of Toronto, where as a member of the board of governors he tenaciously assailed Robert Morrison MacIver, a professor in the department of political economy who was known for his pro-labour views.

Through the Round Table, Leonard had become acquainted with the English writer Lionel George Curtis. In 1923 Leonard purchased a historic home in the centre of London, Chatham House, which he donated to Curtis’s new project, the British (later Royal) Institute of International Affairs. In that same year Leonard extensively revised the terms of an educational trust he had established in 1916 primarily to assist the sons of clergymen, teachers, and war veterans. These terms had been expanded in 1920 and now took their final form, when the fund was increased to $500,000. The trust recitals explain Leonard’s deeply held ideologies. He believed in the natural superiority of the white race, and in the importance of Christianity and the British empire in ensuring the progress of civilization. Hence bursaries were made available to students who were white, British subjects, and Protestant. In addition, no more than one-quarter of the moneys could be awarded to females. Leonard’s goal was to provide financial assistance to needy students who showed the promise of becoming leading citizens of the empire.

These benefactions marked the climax of Leonard’s public life and by the end of 1923 he had become well known in Canada and England. The denouement soon followed. Leonard began suffering symptoms of a neurological disorder now believed to have been Parkinson’s disease. As his health declined, he made an extensive series of donations including large capital grants to Ridley and Wycliffe colleges. He also received a number of tributes and honours, including a doctorate from Queen’s University, conferred in October 1930. Leonard died just six weeks later; even after 20 years of assiduous philanthropy, he left an estate in excess of $4.5 million.

Gifts such as Chatham House stand as enduring memorials. However, it is the Leonard Foundation that serves as the most significant legacy of the man and his times. A relic of the 1920s, the trust’s exclusionary criteria provoked public concern starting in the 1950s. Though Leonard was celebrated in life as a Canadian patriot and philanthropist, his racist beliefs came under scrutiny as the controversy over the trust escalated. A complaint filed against the foundation under the Ontario Human Rights Code in 1986 prompted litigation. In 1990 the Ontario Court of Appeal held that the terms relating to race, religion, nationality, and gender were contrary to law.

Reuben Wells Leonard’s personal papers have not surfaced. It is believed that on his death they were taken by his personal secretary, Henry Collins, with a view to preparing a biography. This work never materialized.

A complete bibliography for Leonard’s life, including the available primary sources, may be found in the author’s Unforeseen legacies: Reuben Wells Leonard and the Leonard Foundation trust (Toronto, 2000), which also reproduces the Leonard Foundation trust deed, dated 28 Dec. 1923. Among the most pertinent sources are Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.3; [R. W. Leonard], “Retiring president’s address,” Engineering Institute of Canada, Journal (Montreal), 3 (1920): 78–84; Re Canada Trust Co. and Ontario Human Rights Commission . . . (1990), Dominion Law Reports (Aurora, Ont.), 4th ser., 69: 321–56; and Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell).

Cite This Article

Bruce Ziff, “LEONARD, REUBEN WELLS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/leonard_reuben_wells_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/leonard_reuben_wells_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Bruce Ziff |

| Title of Article: | LEONARD, REUBEN WELLS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 26, 2025 |