Source: Link

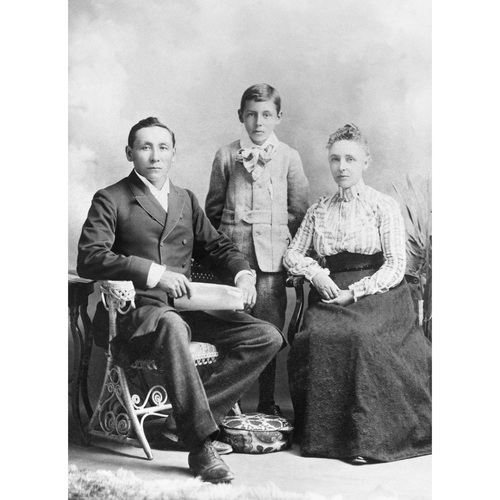

STEINHAUER, EGERTON RYERSON, teacher and Methodist missionary; b. 25 Jan. 1859 at the Whitefish Lake mission (Alta), third son of the Reverend Henry Bird Steinhauer* and the Cree woman Mamanuwartum (Seeseeb, Jessie Joyful); m. 6 Aug. 1889 Sarah Elizabeth Helliwell (1855–1928) at Morley (Mînî Thnî, Alta), and they had one son; d. 21 April 1932 at the Saddle Lake Reserve, Alta.

Three years after Henry Steinhauer was ordained a Methodist missionary in 1855, he established the Whitefish Lake mission among the Woods and Plains Cree. It was located south of Lac La Biche in the wooded parklands north of the North Saskatchewan River, near the northern border of the prairie. The mission was well situated beyond the reach of Blackfoot raiders, on land suitable for farming, near a lake that contained an abundance of fish, and in an area where buffalo still roamed. There Egerton Ryerson Steinhauer was born in 1859.

Settlement of the northwest by European immigrants loomed on the horizon, and less than two decades later, the Whitefish Cree would sign Treaty No.6 [see Kamīyistowesit*] at Fort Pitt (Sask.). Missionaries like Egerton’s father knew that the Indigenous population would soon be a minority, as had become the case in central Canada. The senior Steinhauer belonged to a generation of Ojibwa (Anishinaabeg) Methodists who had been inspired by Peter Jones* and John Sunday [Shah-wun-dais*], and they believed that members of the First Nations could survive, indeed prosper, as Christian farmers. To do so, they would require both education and literacy. While raising their family of five girls and five boys, Henry and Jessie strove with great difficulty to obtain teachers for the isolated mission school; often they remained only for short periods. In 1903 Egerton favourably recalled these early school days: “Sometimes I had the pleasure of going on a buffalo hunt with my parents, who accompanied the band on their annual hunt, the school teacher going as well, and holding school in the open air when circumstances permitted.”

One of the best trained of these teachers was Elizabeth Ann Barrett. In 1886 James Seenum (Pakan), chief of the Whitefish Lake Cree, remembered her stay with the band in 1875–77: “We often talk about her in our camps and about the good she did for us. Our children loved her for all the acts of kindness she did for them, and our women looked upon her with affection.” Under Barrett’s guidance Egerton learned enough to be able to replace her. He taught for two years before he and his younger brother Robert Bird*, accompanied by their brother-in-law, missionary John Chantler McDougall*, left Whitefish to attend Cobourg Collegiate Institute in Ontario to prepare for entrance to Victoria College, where they intended to train as Methodist ministers.

To pay for their studies, the brothers worked during the summers to supplement the assistance their parents could provide. But by 1883 the Steinhauers could no longer afford to keep both sons at school in distant Ontario. Moreover, a teacher was needed at Goodfish Lake, the newly established Methodist Cree community near Whitefish. In 1903 Egerton would explain that, having been accepted to Victoria, he reluctantly made “the sacrifice of my life” and agreed to come home.

During the North-West rebellion led by Louis Riel* in 1885, Egerton, who stood for “peace and loyalty to the Government,” sided with Ottawa and, along with James Seenum, persuaded the local Cree to remain out of the struggle. Steinhauer independently continued his theological training and was ordained in 1889. An impressive-looking individual, described by one commentator in 1903 as “a fine specimen of manhood, tall, well proportioned and straight as an arrow,” he had a sense of humour. He claimed that although not a graduate of Victoria, he was a ba: Robert might be a Bachelor of Arts, but he – Egerton – was “Born Again.”

From the mid 1880s to his death in 1932 Egerton served at a number of Methodist mission stations. He worked in the Whitefish Lake region with the Plains Cree from 1884 until 1885, at Morley with the Stoney from 1886 to 1894, at Fisher River in Manitoba with the Woods Cree from 1894 to 1907, and then with the Plains Cree at Hobbema (now known by its Cree name, Maskwacis) in Alberta from 1907 to 1911. Energetic he truly was. Frederick George Stevens*, the schoolteacher at Fisher River in the mid 1890s, recalled that Egerton made winter trips by dog train across Lake Winnipeg, travelling as far as Norway House at the northern end of the lake, approximately 200 miles from the settlement at Fisher River. He returned to Morley in 1911 and stayed until 1918, when he left to work among the Ojibwa at Saugeen Reserve on Lake Huron in Ontario from 1919 to 1923. In 1920 he and Robert published a Cree hymn-book. Egerton’s final mission was at New Credit with the Mississauga Ojibwa, where he served from 1924 until his retirement in 1926, the year after adherents of the Methodist Church joined Congregationalists and many Presbyterians to form the United Church of Canada [see Samuel Dwight Chown; Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon]. That year Egerton became enfranchised by giving up his Indian status; he wanted to be able to vote and own property like non-Indigenous Canadian males, rights denied to him as a ward of the crown.

Egerton had married Elizabeth Helliwell, a relative of merchant Thomas Helliwell*, in the year of his ordination. A Methodist church worker and teacher at the McDougall Orphanage and Training School in Morley, Elizabeth helped Egerton with a multitude of tasks. In a letter written in 1906 from Fisher River, Egerton noted that their work gave “no opportunity for doing great things.” Rather, “the days often seem hard and disappointing, and the victory – when righteousness and truth shall be established – far off.” Most of their duties consisted of “ministering to the daily wants of the people” and “visiting the sick, providing food, and dispensing medicine as they may need it.”

Egerton and Elizabeth had one son, Wesley Bird, who completed the fourth year of his five-year medical degree at the University of Toronto shortly after his return from service in the Canadian Army Medical Corps during the First World War. For unknown reasons he never finished his final year.

After Elizabeth’s death in 1928 Egerton lived briefly in Calgary and then joined his brother at Saddle Lake, where he assisted at the mission until his death four years later. In his diary Robert mused that Egerton’s sudden passing “must have been caused by his putting too strong an effort in trying to bring his hearers [to] see what Christian life is.” As Egerton himself had written over 20 years earlier from the Battle River Mission station near Hobbema, “I have tried to do my duty as a poor humble tool in God[’]s vineyard, ever since I entered the work.”

Ralph Garvin Steinhauer*, the first Indigenous person to serve as lieutenant governor of Alberta (1974–79), spoke about the missionary brothers in 1955. (His widowed mother had married James Arthur Steinhauer, a grandson of Henry Bird and Mamanuwartum.) Historian Hugh Dempsey was present, and his notes record that Steinhauer warmly recalled Egerton, whom he knew in the early 1930s, after the latter had moved to Saddle Lake. Egerton, then in his early seventies, had been a great athlete and he encouraged the reserve’s young people to participate in sports, telling them to “never let yourself think that you are not as good as the white man.” Egerton also challenged them about education and tried to plant seeds of ambition: “If you people don’t perk up and follow the white man’s way in business, you’ll find yourselves left out in the cold! Can’t you become doctors, lawyers or businessmen?” Besides encouraging younger people to pursue worldly success, he addressed spiritual matters, describing the Sun Dance as a form of worship, and declaring that pagan natives who attended such ceremonies were witness to “some great prayers said – heartfelt and sincere.” He saw many of the same core values in both Christianity and Cree spirituality. For Egerton Ryerson Steinhauer, there was no contradiction between his dual Indigenous and Christian heritage.

GA, George and John McDougall family fonds, M-729-56 (N.W. Territories marriage reg.: Methodist Church Mission, Morleyville – 1884–1896, 1906), E. R. Steinhauer and S. E. Helliwell; Robert Bird Steinhauer fonds, M-1174-19; Micro-Steinhauer, diaries, 1887–1937. LAC, RG10-B-3, vol.7275, file 8118-2 (Saddle Lake Agency, enfranchisement, Rev. R. B. Steinhauer and Rev. E. R. Steinhauer); RG150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 9266-17. Private arch., D. B. Smith (Calgary), Copy of Hugh Dempsey’s notes of 1955 talk by R. G. Steinhauer. UCC, F3 (Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Soc. coll.), Acc. 1978.128C, box 42, file 308 (Henry Steinhauer, 6 May 1861); F14 (Methodist Church (Can.) Missionary Soc. fonds), Acc. 1978.092C, box 7, file 139 (E. R. Steinhauer, 3 Feb. 1909); F3188 (Frederick George Stevens fonds), autobiographical sketch. UTARMS, A73-0026/423(99). Christian Guardian (Toronto), 2 April 1879. New Outlook (Toronto), 20 Feb. 1929, 20 April 1932, 4 May 1932. Regina Leader, 19 Oct. 1886. Cree hymn book, rev. R. B. Steinhauer and E. R. Steinhauer (Toronto, 1920). “In memoriam: James Arthur Steinhauer, 1882–1969” (unpublished pamphlet, Saddle Lake, Alta, 1969; copy held by DCB). I. K. Mabindisa, “The praying man: the life and times of Henry Bird Steinhauer” (phd thesis, Univ. of Alta, Edmonton, 1984). Methodist Church (Can.), Missionary Soc., Annual report (Toronto), 1877/78: xvi. “[Letter from] Rev. E. R. Steinhauer,” Missionary Bull. (Toronto), 1 (1903–4): 251–52 “Letter from Rev. E. R. Steinhauer,” Missionary Bull., 3 (1905–6): 819–21. D. B. Smith, “Elizabeth Barrett,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 46 (1998), no.4: 19–28; Mississauga portraits: Ojibwe voices from nineteenth-century Canada (Toronto, 2013); “The Steinhauer brothers: education & self-reliance,” Alberta Hist., 50 (2002), no.2: 2–11; “Worlds apart,” Canada’s Hist. (Winnipeg), October–November 2017: 31–37. M. D. Steinhauer, Shawahnekizhek: Henry Bird Steinhauer, child of two cultures (Goodfish Lake, Alta, 2015). Varsity (Toronto), December 1916, suppl.: 80.

Cite This Article

Donald B. Smith, “STEINHAUER, EGERTON RYERSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/steinhauer_egerton_ryerson_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/steinhauer_egerton_ryerson_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald B. Smith |

| Title of Article: | STEINHAUER, EGERTON RYERSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2023 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |