Source: Link

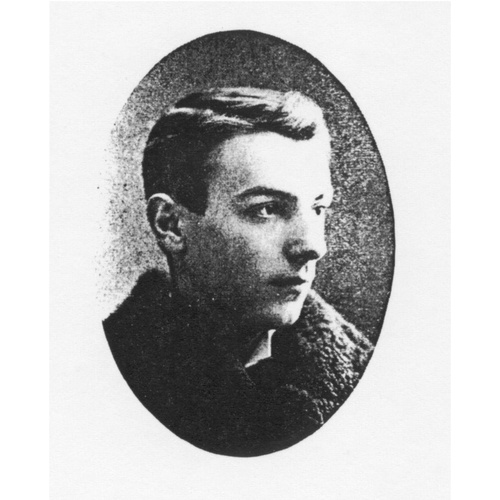

SAINT-PIERRE, TÉLESPHORE, newspaperman and writer; b. 10 July 1869 in Lavaltrie, Que., son of Jean-Baptiste Saint-Pierre, a farmer, and Azilda Lapierre; m. Stéphanie Guérin, and they had one son and two daughters; d. 25 Oct. 1912 in St Boniface, Man.

In 1878 Télesphore Saint-Pierre’s family left Montreal, where they had lived since 1872, and settled in Detroit. After a year of schooling in English, Télesphore was apprenticed as a typographer to Rousseau et Fils, a printer in that city. He spent the rest of his life in the printing and newspaper world, which fed his passion for great causes and his taste for study. The account of Médéric Lanctot*’s sojourn in the American west (he had come to Detroit in 1868 and in 1869) and of his crusade for the annexation of Canada to the United States intrigued him; the Métis uprising in the Canadian northwest sparked his imagination. At the time Louis Riel* died in 1885, Saint-Pierre, although only 16, became the editor of Le Progrès (Windsor, Ont.) and took part in the struggle against the Conservatives in Canada. In 1888 he and his friend Charles Guérin (who was the same age as he) established L’Ouest français in Bay City, Mich., but the venture failed. In 1889 the two were in Lake Linden, Mich., where they founded L’Union franco-américaine.

At Lake Linden, as at Bay City, Saint-Pierre threw himself into the cause of the French Canadians in Michigan and in Essex County, Ont. It was a subject he knew well. For years he had spent his spare time at the Detroit Public Library, reading everything he could find on the history of French Canada. He estimated that there were 140,000 French Canadians or individuals of French Canadian origin in Michigan by 1890. These people, he noted, were prepared to make many sacrifices to preserve their ancestors’ language, ways, and customs. Although only 20, Saint-Pierre was involved on all fronts in the struggle for the survival of the French fact. His newspaper columns recalled the heroic struggles of the past, praised the courage and devotion of the Catholic clergy and the directors of mutual benefit societies, and castigated the unreliable, as well as the bishops who were still unwilling to authorize the creation of “national” parishes and entrust them to French Canadian parish priests.

But times were difficult. Before the end of 1889, Saint-Pierre left the editorship of L’Union to Guérin and returned to Montreal to try his luck. Then came the ten most productive years of his short career. He was in turn an editor at La Patrie, La Minerve, Le Canada, Le Soir, the Gazette, and the Montreal Daily Herald. In 1894 and 1895 he was president of the Parliamentary Press Gallery and he was twice chosen secretary of the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada. A Liberal in politics and a great admirer of Wilfrid Laurier, he attacked the protectionist policy of the Conservatives which, he argued, had led only to “disorder, corruption, and disaster.” He devoted his spare time to writing. In 1894 he brought out a pamphlet, Theory and facts: a complete review of the development of Canada under protection (Montreal), and a book entitled Histoire du commerce canadien-français de Montréal, 1535–1893. The latter volume, a handsome work embellished with engravings, portraits, and biographies of businessmen, was commissioned by the Chambre de Commerce du District de Montréal. The following year, at the age of 26, Saint-Pierre published a remarkable book, Histoire des Canadiens du Michigan et du comté d’Essex, Ontario. It, along with a series of articles and lectures, provides an excellent introduction to his ideas about the French presence in North America.

“The 65,000 colonists abandoned by France,” wrote Saint-Pierre, “have become a people three million strong, united by community of faith, language, and aspirations.” He asserted that “an invisible hand directs events to give the [French] Canadian people its distinct character.” Within Quebec, its members resisted the conquerors’ attempts to assimilate them; better still, their growth and increasing influence diluted the English element that was supposed to submerge them. In the United States, as their numbers increased, so too did their cohesiveness. They were now gallicizing New England after having swarmed into the Midwest. According to Saint-Pierre, there would be some 25 million French Canadians at the dawn of the 21st century, and half would be in the United States. When the centrifugal forces working within the Anglo-Saxon race “produce their usual effects, they will take their place among autonomous nations.”

Responding to the problem of French Canadian dispersal caused mainly by emigration, Saint-Pierre urged the élite of Quebec to curb the movement and persuade those bent on leaving that the cities of the province offered as many attractions as the urban centres of the United States. He reminded those who had lived in the United States, as he had, that the majority of emigrants “are no richer than the day they arrived . . . a mere handful have achieved real comfort.”

Saint-Pierre was equally convinced that attempts to repatriate emigrants were inadvisable. Such projects impoverished those participating in them and disorganized Canadian parishes in the United States; they increased the danger of emigrant French Canadians’ losing their language and faith. It was more important for the Quebec élite to try to ally itself with the people who had left and to help them in their struggles. Saint-Pierre made such efforts himself when he was the editor of L’Opinion publique of Worcester, Mass., from 1899 to 1903. In the latter year he settled in Winnipeg, where he worked as an editor at the Manitoba Free Press and founded a short-lived paper, L’Ouest canadien. In both places he tirelessly pursued the same themes and struggles as he had in Michigan a few years earlier, but he was now more optimistic.

Observing the sizeable decline in emigration to the United States from the turn of the century, Saint-Pierre saw “the beginning of a new era in the tide of French expansion in North America.” People continued to emigrate from Quebec, but departures were in large part balanced by returns. This trend seemed very positive to him. According to Saint-Pierre, “It is essential for the perpetuation of the French idea within colonies transplanted to the United States that from time to time they receive new blood from the mother country and that continuous relations are in this way maintained.” The decline of emigration thus enabled French Canadians to strengthen themselves in Canada without causing communities gained beyond the border to be abandoned.

Through all his days Télesphore Saint-Pierre devoted himself to the cause of French-speaking people in both Canada and the United States, ardently supporting them in his newspapers, publications, and lectures. He made this commitment the struggle of a lifetime.

In addition to his numerous contributions to the newspapers with which he was involved, and the publications mentioned in this biography, Télesphore Saint-Pierre’s writings include: Histoire de la race française aux États-Unis (Detroit, 1886); Les Canadiens des États-Unis; ce qu’on perd à émigrer (Montréal, 1893); Le citoyen américain; ses devoirs et ses droits (Worcester, Mass., 1902); “La marche ascendante de notre race; trois millions de Canadiens français en Amérique” and “Les sociétés et les conventions canadiennes aux Etats-Unis” in Fête nationale des Canadiens-français . . . , H.-J.-J.-B. Chouinard, compil. (4v., Québec, 1881–1903), vol.4 (1902): 441–69; “Le nombre des descendants français aux États-Unis,” La Rev. franco-américaine (Montréal), 10 (1912–13): 90–99; and “Cinquante années de régime américain dans le Michigan – 1796–1846,” in Les quarante ans de la Société historique franco-américaine (Boston, 1940), 41–61.

ANQ-M, CE5-6, 10 juill. 1869. Alexandre Belisle, Histoire de la presse franco-américaine . . . (Worcester, 1911). Donald Chaput, “Some Repatriement dilemmas,” CHR, 49 (1968): 406–7, 410–11. Dictionnaire de l’Amérique française; francophonie nord-américaine hors Québec, Charles Dufresne et al., édit. (Ottawa, 1988), 334.

Cite This Article

Yves Roby, “SAINT-PIERRE, TÉLESPHORE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/saint_pierre_telesphore_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/saint_pierre_telesphore_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Yves Roby |

| Title of Article: | SAINT-PIERRE, TÉLESPHORE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |