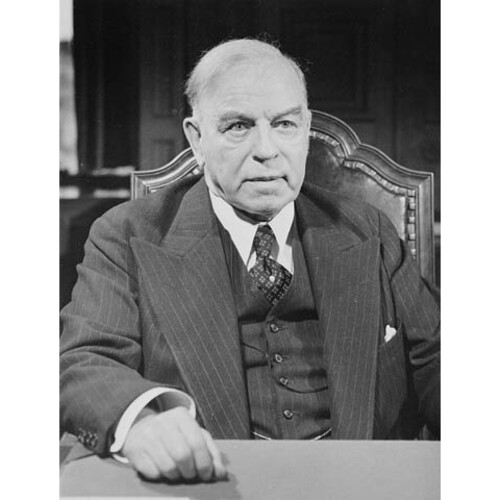

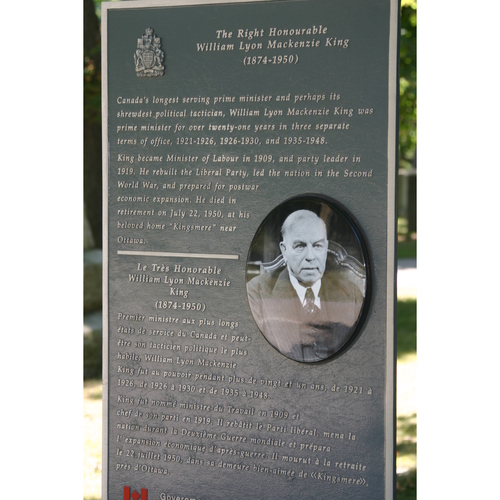

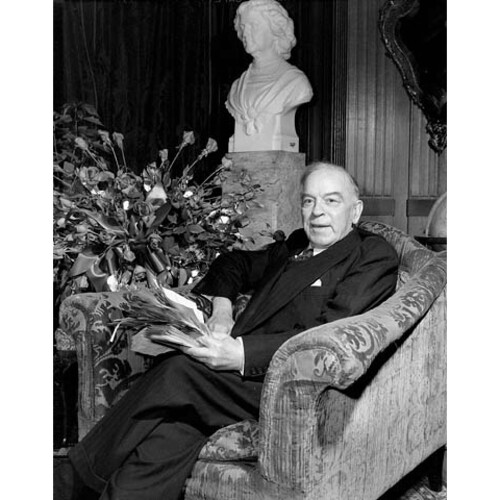

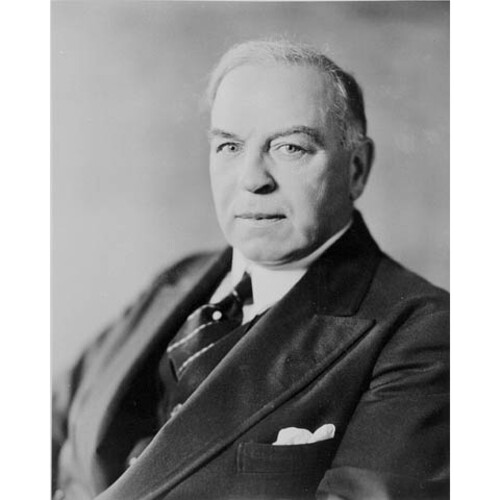

KING, WILLIAM LYON MACKENZIE, journalist, civil servant, author, labour conciliator, and politician; b. 17 Dec. 1874 in Berlin (Kitchener), Ont., son of John King and Isabel Grace Mackenzie*; d. unmarried 22 July 1950 at Kingsmere, Que.

William Lyon Mackenzie King had a long political career. He was leader of the Liberal Party for 29 eventful years through the buoyant expansion of the 1920s, the depression of the 1930s, the shock of World War II, and then the post-war reconstruction, and for 21 of these years he was Canada’s prime minister. His decisions during this time contributed significantly to the shaping of Canada and to its development as an influential middle power in world affairs. During his lifetime his achievements were sometimes obscured by a style notable for its compromises. After his death his political career was sometimes overshadowed by the revelation of his unsuspected personal idiosyncrasies.

King’s father, who had spent time in Berlin as a youth, met his future wife in Toronto when he was a university student there. Isabel Mackenzie, a daughter of William Lyon Mackenzie*, was born in the United States while he was in exile, and her early years were marked by poverty and insecurity. Matters did not greatly improve after the family returned to Toronto; Mackenzie lived as a gentleman but never earned enough money to sustain his lifestyle. For Isabel, marriage to John King, who went into law, held out some promise of financial security. King, however, decided to give up his prospects in Toronto and to return to Berlin in 1869 to practise law and it was there that Willie, as he was called, spent his childhood. Willie and his two sisters and a brother had happy memories of their early years. Woodside, the home the family rented from 1886 on the outskirts of Berlin, was an attractive brick house surrounded by a large garden. As a child Willie was healthy and active, with a self-assurance that sometimes got him into trouble and a ready smile, which often minimized his punishments. He was a good student, active in debates and sports, popular among his peers, and trusted by his elders. His family was close-knit and in later years King looked back with nostalgia to memories of family games and hymn singing with his mother at the piano.

These years were less idyllic for his parents, whose serious financial problems would plague them for the rest of their lives. John King was not a success as a lawyer. He lacked the aggressiveness to build up his practice, the conflicts and scandals of one of his uncles (a local newspaperman) negatively affected the family, and the German community in Berlin patronized German-speaking lawyers. His income was not enough to pay for the servants and keep up appearances, and the family was soon in debt. He became withdrawn and Isabel became frustrated and shrewish. A move back to Toronto in 1893, after Willie had started university, changed little. A lectureship at the Law School at Osgoode Hall brought in some money but John King failed to get a professorship and his practice produced little income. Willie knew nothing of this situation as a child, but he was marked by the experience. He absorbed his parents’ social values and came to be embarrassed by their shabby gentility; he learned as well to sense the moods of his parents and to avoid confrontation. More significantly, his mother gradually came to think of him as the person who might be able to give her the status and security her husband could never provide. It was a burden from which the young Mackenzie King would not be able to escape.

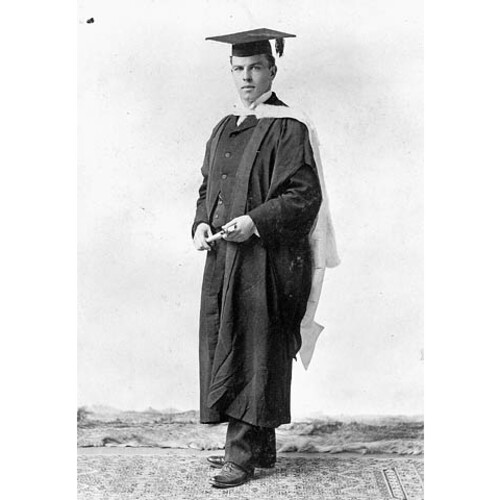

King enrolled at the University of Toronto in 1891, taking the honours program in political science. A disciplined and well-organized student with the advantage of a good memory, he graduated with first-class honours, standing second in his class. He was not an academic grinder, however, and found time for sports, contributed to the Varsity, and spent many hours discussing the purpose of life and its moral obligations with other serious-minded students. He stood out among his classmates, was elected president of his class in his first year, and in 1895 was a leader of a student strike to protest the arbitrary dismissal of a popular professor, William Dale*. He was still known as Willie to his family but at university he adopted W. L. Mackenzie King as his signature and was called Mackenzie by other students. Though the name suggests a more formal self-image, it also reflects King’s closer identification with his grandfather, who even then he saw as an early champion of responsible government and political liberty. In later years a few close friends in England, including John Buchan*, called him Rex, but there would be none of this easy familiarity with his colleagues or acquaintances in Canada.

As a young man King was a practising Presbyterian and, indeed, he would attend church regularly throughout his life. His correspondence and diary from his student years refer constantly to spiritual values and his personal dedication to Christian duty. If his religious views seemed sentimental and sometimes self-justifying, they were nonetheless influential. He might have been priggish but his faith also led to good works. In addition to his student activities, he participated in a men’s reading club in a working class district in Toronto and he regularly visited patients at the Hospital for Sick Children. He even made a few attempts to reform prostitutes, although on these occasions his Christian motives were likely supplemented by the prurience of a repressed young man. More noteworthy was the influence on him of Arnold Toynbee’s work on the Industrial Revolution, which led King to the conclusion that industrialism was the pre-eminent challenge to Christianity at the end of the 19th century. This theory attracted him to social reform but not to socialism. He saw no distinction between his religious faith and a liberal commitment to build a better society on earth, but his emphasis was on conversion, not coercion.

King’s sense of Christian obligation was combined with a strong personal ambition. He nonetheless remained undecided about what profession to pursue. His father encouraged him to become a lawyer and after completing his ba at Toronto in 1895, he did take a one-year llb there. He was not interested in practising law, however. He talked of a possible career in the church or in politics, and between 1895 and 1897 he wrote for a number of Toronto newspapers, but mas at Toronto and Harvard and fellowships in political economy at the University of Chicago and Harvard seemed more likely to lead to an academic future. After a summer stint as a journalist, writing articles for the Toronto Globe on local sweatshops, he began work at Harvard on a doctoral thesis on labour conditions in the clothing industry. This scholastic pattern was interrupted by a telegram in June 1900 from William Mulock, Canada’s postmaster general who was also responsible for the newly formed Department of Labour. King had already drawn Mulock’s attention to the link between sweatshops and federal contracts for postbags and Mulock now offered him the editorship of the proposed Labour Gazette. King yielded to family pressure, to the attractions of financial security, and to what he saw as an opportunity for public service, and he accepted the job. He arrived in Ottawa in late July. The following month Mulock also offered him the position of deputy minister of labour, which he formally took up on 15 September.

He joined the department at a crucial time in the development of industrial relations. In the early years of the 20th century the conflict between labour and capital seemed irrepressible. Trade unions offered some possibility of collective action by workers but employers could frustrate organizers and break strikes by forcing their way across picket lines through the use of injunctions, the police, or the militia. Violence seemed to be the only effective response. King saw the Labour Gazette as an important contribution to labour relations. It would publish tables of strikes and lockouts, summaries of court decisions, and regional accounts of working conditions, wage settlements, and costs of living. He knew the importance of earning a reputation for being non-partisan and with the help of his university friend Henry Albert Harper*, whom he appointed assistant editor, the Gazette soon became a respected reference, though as early as 1901 it came under attack from the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association.

King’s ambitions did not stop with the Gazette. He was soon writing speeches for his minister that associated Mulock and the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier* with a policy of fair wages for its employees; he also took the initiative to offer his services to employers and workers in the settlement of strikes and lockouts. King quickly showed a remarkable talent for conciliation. Exceptionally patient, he regularly won the confidence of leaders on both sides by listening carefully to their concerns, and he was remarkably sensitive to their unspoken hopes and fears. On many occasions he was able to devise compromises which both sides could accept. One dispute with important consequences was the coal strike in Lethbridge, Alta, in 1906 [see Frank Henry Sherman*], which threatened to leave westerners vulnerable to the rigours of a prairie winter. Sent west by his new minister, Rodolphe Lemieux*, King negotiated a settlement and then went on to draft legislation to establish formal procedures to defuse similar strikes. The Industrial Disputes Investigation Act of 1907 postponed any strikes in a public utility or a mine until a conciliation board had resolved the conflict or, failing that, had published a report on the facts and suggested terms for a settlement. The act did not prohibit a strike but its original feature was to enforce a cooling-off period and to expose the disputants to the pressure of public opinion to encourage a resolution.

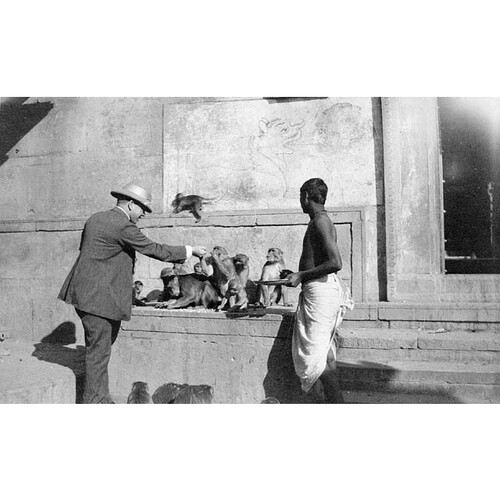

King’s success in conciliation led the government to call on him to troubleshoot a wide range of problems. He served on royal commissions dealing with industrial conflicts in British Columbia (1903), at Bell Telephone in Toronto (1907), and in the cotton industry in Quebec (1908), and with the problem of compensation to Japanese and Chinese residents arising out of riots in Vancouver (1907-8). He even undertook a quasi-diplomatic mission to London, England, to convey the concerns of American president Theodore Roosevelt and the Canadian government on the issue of Japanese immigration to North America. These were major responsibilities for a civil servant, but King still found it frustrating not to be in a position to make political decisions. Consequently, on 21 Sept. 1908, he resigned as deputy minister to devote his talents to active politics.

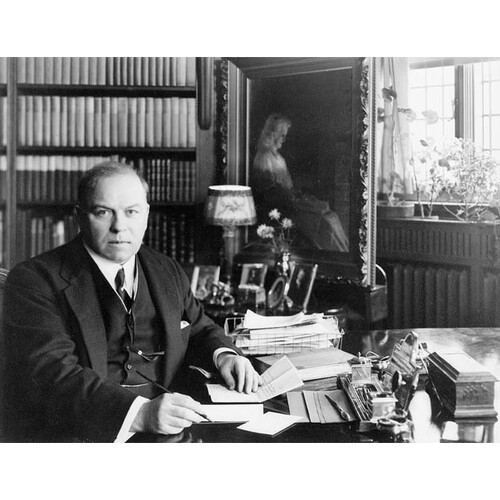

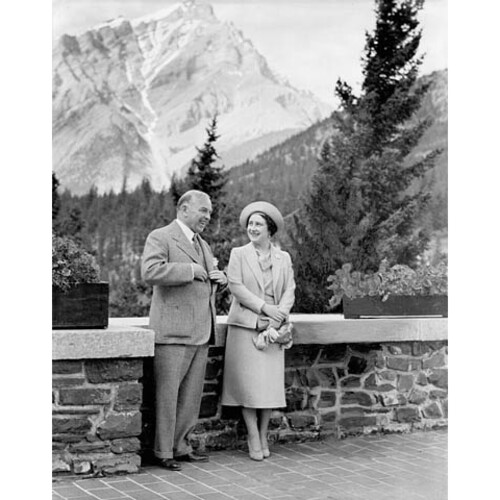

He was now 33 years of age. His career in the civil service had been remarkably successful but he had also found time to lead an active social life. In Ottawa he was seen by many, including Governor General Lord Grey*, as a man to watch. He was a regular guest at the dinners and balls of Ottawa’s elite. He enjoyed the company of women and expected to get married eventually – as a graduate student in Chicago he had proposed to a nurse – but his caution, his obligations to his family, and his reluctance to accept any fetters on his ambition probably account for his avoidance of the commitments of married life. He paid off his father’s debts and regularly responded to his mother’s appeals for money for clothes or housekeeping expenses. In the Gatineau hills of Quebec, north of Ottawa, he and Bert Harper had long walks, were enchanted by the area around Lac Kingsmere, read uplifting literature, and shared their spiritual concerns. Their friendship ended in December 1901 when Harper died trying to save a young woman from drowning. King wrote a touching memoir, The secret of heroism, but he never again gave himself over to a close friendship. Before Harper’s death, he had acquired property at Kingsmere and built a small cottage as a refuge from the pressures of Ottawa. More and more, however, his career would overshadow his private life.

In the federal election of October 1908 King presented himself as the Liberal candidate in the riding of Waterloo North, which included Berlin. The riding had been held by a Conservative but King won it by a small margin. On 2 June 1909, soon after the first session of parliament had ended, Laurier appointed him minister of labour. King proceeded cautiously, aware that his senior colleagues saw him as an upstart and were dubious about his progressive views. On the labour front the new minister’s intervention in 1910 in the Grand Trunk Railway strike, which led to the blacklisting of workers and the loss of pensions, hurt the government. At the same time, he introduced the Combines Investigation Act of 1910, which established machinery to investigate alleged restraints of trade or price manipulation and authorized fines for those operating contrary to the public interest. He also spoke of the need for a bill for an eight-hour day but his legislative activity was interrupted by the reciprocity agreement and the federal election of September 1911. The government was defeated and, more serious for King, he lost his seat because reciprocity proved to be unpopular among the industrialists and factory workers of Berlin.

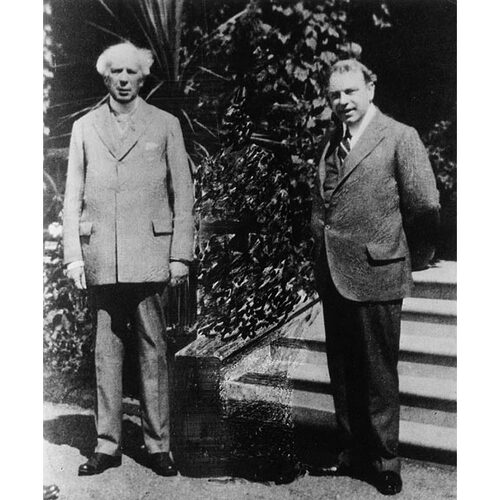

King’s defeat was a setback but he remained committed to a political career. To earn his living he gave speeches, wrote political articles and pamphlets, and ran the Liberal Party’s new central information office in Ottawa, a job that included editing the Canadian Liberal Monthly. Then, in 1914, he received an unexpected offer. John Davison Rockefeller Jr had found himself harshly criticized for a bitter miners’ strike in Colorado; he knew nothing about it but was blamed because the mine belonged to his family. His response was to ask King to direct a study for the Rockefeller Foundation on industrial relations. When the two men met, they were mutually impressed. King saw a man who was naive about the obligations of employers but who seemed receptive and sincerely committed to reform, while Rockefeller saw a mentor who could guide him through this industrial quagmire. King agreed to conduct the study using the Colorado strike as a test case, and he was given permission to remain politically active in Canada. He first went to Colorado to meet the management and workers and then involved the young industrialist in negotiating a settlement, which resolved the conflicts over wages and working conditions and arranged for the election of workers to grievance committees. This negotiated plan was open to the objection that it provided for a “company union” instead of an independent union that could be less easily intimidated by management. King saw the arrangement as a necessary first step, however, and he received some credit for insisting on inclusion of the miners’ right to join a union and the right of organizers to campaign for members.

Published in 1918, Industry and humanity: a study in the principles underlying industrial reconstruction (Toronto) was King’s report to the Rockefeller Foundation. The book had little impact because its analysis was laboured and abstract; his arguments drew on Toynbee, James Mavor* at the University of Toronto, and other theorists. His thesis, however, was a serious attempt to put industrial relations in a broader social context. A reformer but not a radical, King rejected the ideas of an inevitable class struggle. Labour, management, and capital were partners, not rivals, and conflict happened when there were grievances that the other partners did not fully appreciate. Industrial peace could be restored only if the partners recognized they had common interests and if there were structures wherein interests could be explained and understood. King broadened the debate further by arguing that the community was a fourth partner and its interests must also be considered. Industry and humanity never adequately clarified how the community’s voice could be expressed in negotiations but King’s theory could be used to justify government intervention if the community’s interests were ignored. Even if the book attracted minimal attention, it is important for the light it throws on his subsequent success as a politician. In politics, more interest groups were involved and the issues were often more complex, but for King the basic assumption of common good was the same. Leadership did not mean imposing policies or adopting ones because they were popular. It meant a cautious and incremental approach: discussions in cabinet and caucus, which could be heated and protracted, with the leader ensuring that all points of view were presented and that a consensus would be reached.

King could derive some satisfaction from his work for the Rockefeller Foundation, which he left in February 1918, and from subsequent contracts as an industrial consultant in the United States. Back in Canada, however, his political career had not been going well. He had gained the Liberal nomination for York North in Ontario in 1913 but had spent little time in the riding. Then in 1917, in the midst of World War I, Sir Robert Laird Borden*, the Conservative prime minister, opted for a policy of conscription for overseas service and proposed a coalition of Conservative and Liberal mps to form a government to introduce this policy. Many French Canadians saw it as an attempt by the English Canadian majority to force them to fight in a primarily European war. King tried to avoid taking a position but when Laurier insisted on opposing conscription, he accepted the party line. In the federal election of 1917 the newly formed Union government, which included Conservatives and conscriptionist Liberals, won a sweeping majority, with the opposition Liberals taking most of their seats in Quebec. In York North, King once again failed to get elected.

King’s private life was also disrupted during these years. He had been an eligible bachelor for many years but his emotions became more and more centred on his family. The family, however, was narrowing. One of his sisters died in 1915, followed by his father the next year. His mother became more demanding, but King idealized her; he thought of her as the only person who appreciated him and believed in his political future. By this time she was an invalid; King installed her in his Ottawa apartment in late 1916 and nursed her through a series of crises. She passed away the day after his defeat in York North, before he could get back to Ottawa. With her death King felt painfully alone. Not surprisingly, he often thought of her and felt her presence. His interest in a world beyond the material world, which had its roots in his Christian faith, was heightened by this loneliness.

Politics soon filled the void. Laurier died in February 1919, shortly after the war and before the Liberal Party had recovered from its split over conscription and crushing electoral defeat. In August, for the first time in Canada, a federal party opted for a leadership convention instead of allowing the caucus to select a new leader. William Stevens Fielding*, Laurier’s long-serving finance minister, would have been the obvious successor in spite of his 70 years, but he had supported the Unionists and many Liberals, especially French Canadian Liberals, would not forgive this disloyalty. King had the advantage of being young and energetic as well as a recognized expert on the disturbing social and industrial questions of the day. It was a close contest but King’s loyalty to Laurier gave him the advantage. On 7 August he had the support of most of the Quebec bloc and enough backing from delegates from other regions to be chosen leader on the third ballot.

King won the leadership at a time when Canadian politics had never been more volatile. The Union government had no future now that the war was over. Arthur Meighen*, who succeeded Borden as prime minister in 1920, tried to prepare for the next election by reorganizing the Conservative Party and campaigning on its customary platform of tariff protection. Many Canadians, however, had lost confidence in traditional politics. Wartime inflation and post-war industrial unrest led many workers to look to radical solutions, including socialism, militant action, changed forms of union organization, and new visions of social and political order. The year 1919 was one of strikes, most notably the Winnipeg General Strike, with leaders often using the rhetoric of class struggle to justify their demands. Almost as dramatic was the radicalization of farmers, who saw the prices for their products drop and who blamed transportation costs and tariffs for their financial difficulties. In Ontario and on the prairies many farmers who had supported the Union government now rejected the Conservatives and the Liberals in favour of the Progressive Party, which would be formed on the national level in 1920 when members of the Canadian Council of Agriculture united with dissident Liberals led by Thomas Alexander Crerar*.

Politicians would also have to come to terms with an unstable world beyond Canada’s borders. For most Canadians this adjustment meant redefining the country’s relations with Britain. Canada had entered the Great War as a colony but its experience during the war had many convinced that a subservient colonial status was no longer acceptable. At the same time few wanted total independence. The options ranged from a more centralized British empire, in which Canada would have an influential role, to a loosely associated commonwealth of nations in which the emphasis would be on Canadian autonomy. The implications for Canada were far from clear but change was in the air.

The Liberal Party that had chosen King as its leader was itself deeply divided. King would have to win back the Liberals who had supported the Union government and conscription without alienating the French Canadians. At the same time he would have to make the party more hospitable to the new labour and farm groups, which meant reducing tariffs and giving more social assistance to the less privileged while retaining the support of the industrialists. The Liberal convention of 1919 did propose a forward-looking platform that favoured lower tariffs without opting for free trade and approved of unions, better working conditions, and public insurance for the sick, the aged, and the unemployed. This platform was more an aspiration than a commitment, however, one to be adopted “in so far as the special circumstances of the country will permit.” King too was cautious; in his acceptance speech he was careful to describe the platform as a “chart” and not a contract. The new leader needed to construct a majority party in a divided country but he clearly intended to move slowly.

King wanted to get into the House of Commons as soon as possible. He had a choice of ridings but in most cases he would have had to run against a farmers’ party candidate. To avoid any confrontation he picked Prince, in Prince Edward Island, where he was acclaimed in October 1919. Once in the house he was careful to give W. S. Fielding a major role in the debates, a move that both reassured the conscriptionist Liberals and gave King time to familiarize himself with the current issues. He took the opportunity in 1920 to tour Ontario and the west, making a point of expressing sympathy for the farmers’ problems and meeting with Progressive leaders to suggest some collaboration against the common Conservative enemy in the next election. The Progressives, who were riding a political crest, showed little interest. At the provincial level organized farmers won elections in Ontario (1919) and Alberta (1921), and were so strong in Manitoba and Saskatchewan that the Liberals there had to distance themselves from their federal counterparts in an effort to survive. It was revealing that after King was nominated in his old riding of York North for the next election, Ralph W. E. Burnaby, president of the United Farmers of Ontario, was nominated to run against him. It would not be easy to convince farmers that the Liberal Party had changed its ways.

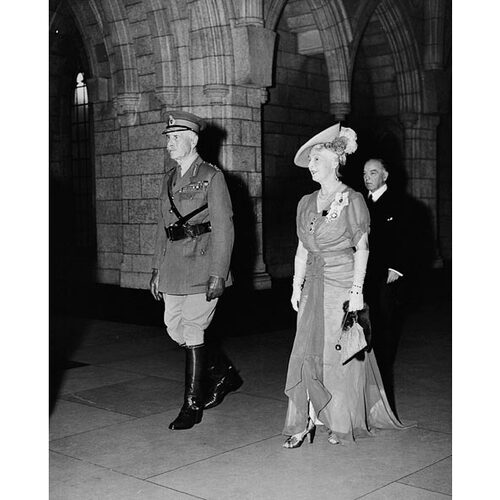

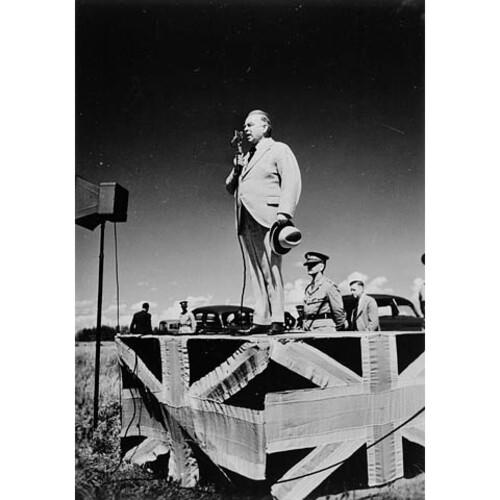

The election of December 1921 – the first in which all women would vote – was a graphic illustration of how fragmented the country had become. Meighen was burdened with the unpopularity of the Union government and his role in guiding the conscription legislation through the house. His defence of the tariff was largely ignored in Quebec, where conscription was still vividly remembered, and attracted little support in the west or the Maritimes. Only 50 Conservatives were elected, 37 of them from Ontario. The Progressives were surprisingly successful, taking 38 of the 43 prairie seats and 24 in Ontario; among their number was Agnes Campbell Macphail*, Canada’s first female mp. The Liberals achieved victory with 116 seats, a bare majority; enjoying representation from every province except Alberta, they could claim to be the only national party. With 65 of their seats from Quebec, however, the Liberals’ dependence on French Canadian voters was a major concern. King had won the election and thus became prime minister (and ex officio secretary of state for external affairs); in due course, on 3 June 1922, he would be sworn to the British Privy Council, an honorific appointment he valued most because he felt it vindicated his grandfather’s “great purpose & aim.”

King was still on trial. He would need to broaden the basis of Liberal support without alienating his own supporters and he would have little margin for error. His first decision was crucial. King knew that the Liberal Party had to retain the support of French Canada. He could read French but spoke it haltingly; the larger problem was more cultural than linguistic. To ensure that his government would not ignore the French Canadian point of view, he resolved that his closest colleague would come from Quebec. His choice was Ernest Lapointe, a backbencher and lawyer who had earned a reputation as a moderate Liberal and a champion of French Canadian rights. King called him to Ottawa immediately after the election, explained the role he would be expected to play, and offered him the justice portfolio to confirm his position. The most prominent figure among the French Canadians elected from Quebec was Sir Lomer Gouin*, a former premier of the province, but King was suspicious of his liberalism because of his protectionist leanings and close ties with Montreal’s business community. King eventually yielded to the political pressure to give justice to Gouin – Lapointe got marine and fisheries – but he made it clear that Lapointe was his chief lieutenant. This status was publicly corroborated in 1924 when Gouin resigned and Lapointe became minister of justice. King and Lapointe would work closely together for almost 20 years, until Lapointe’s death in 1941.

The next issue for King was the cabinet representation from the west. This was important because he saw the cabinet as the central institution of government. Policy was expected to emerge from debates there, with ministers defending the interests of their region and King playing the role of mediator. In 1921 his task, as he understood it, was to consolidate the anti-Conservative forces, a seemingly simple undertaking. The Liberal and Progressive parties were both opposed to the high-tariff policies of the Conservatives and they both favoured greater autonomy in Canada’s relations with Britain. If Progressive leaders entered cabinet, the farmers’ point of view would be effectively presented and the emerging consensus would more adequately reflect a balanced national perspective. The difficulty was that the Liberal and Progressive parties both had deep internal divisions, which left their leaders with little room to manoeuvre. T. A. Crerar, the Progressive leader and mp for Marquette, Man., was tempted by the offer of a cabinet post; when he asked King for policy commitments on tariffs and railways, however, he got sympathy and understanding but no specific promises. The more radical Progressives made it clear that if he did enter the government he would not have their support. King eventually had to concede defeat and turn to elected Liberals to form his cabinet.

For the next few years the Progressives were never far from King’s mind. The farmers’ concerns continued to be his preoccupation and in cabinet he represented, as best he could, the interests of those who were absent. The Crowsnest Pass agreement, which gave preferential freight rates on grain moving eastward from the prairies on the railways and some commodities westward, had been suspended in 1919 in response to wartime inflation but it was restored by the government in 1922. The government also committed itself to creating a railway system out of the bankrupt lines it had acquired during the war [see William Costello Kennedy*] and agreed to complete the Hudson Bay Railway to placate the farmers who wanted a shorter link to salt water. For most farmers, however, the real test would be tariff changes and here the government’s record was ambivalent. Although King argued in cabinet for some dramatic gesture, he had little support and Fielding, once again minister of finance, included few tariff reductions in his budgets of March 1922 and May 1923. Some Progressives split with their party to support the first budget but it was a sign of the farmers’ frustrations that all of the Progressives voted with the Conservatives against the second.

King’s effort to unite the anti-Conservative forces fared better in international affairs. As prime minister, Meighen had continued Borden’s policy of preserving the diplomatic unity of the empire, though at the Imperial Conference of 1921 he had opposed the renewal of Britain’s alliance with Japan, recognizing that the United States had interests in the Pacific and wanting to maintain good Canadian-American relations. King too understood that imperial affairs abroad could have profound consequences for Canada. Within months the difficulties of maintaining imperial diplomatic unity were again exposed, dramatically, by the Çanak crisis. In September 1922 the Turkish government, in repudiation of a treaty it had signed with the allied powers, threatened to reoccupy the neutral zone of Çanak on the Dardanelles strait (Çanakkale Boğazi). Britain was determined to block this action, by force if necessary. With no prior consultation it appealed to the prime ministers of the dominions to provide military support and then released a statement to the press. King, who had not received the official message, first heard of the crisis from a journalist. His response, after meeting with the cabinet, was to refuse any participation without the consent of parliament. This assertion of autonomy was in sharp contrast to Meighen’s statement, in a speech in Toronto on 22 September, that Canada should have replied to Britain “Ready, aye ready; we stand by you.” King was careful to keep Crerar informed during the crisis and the Progressives openly supported his position. The Turks fortunately backed down, but the implications of Çanak could not be ignored. There would be no common imperial foreign policy if each dominion decided its own course of action.

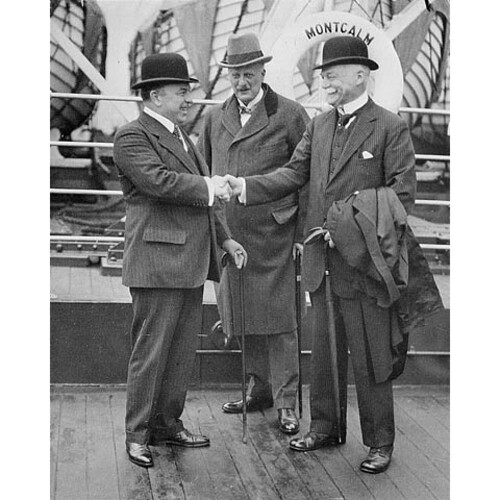

The Imperial Conference of 1923 could not disregard this challenge. The British government, with support from Australia and New Zealand, hoped that the conference would approve a broad statement on foreign policy. King was convinced that any attempt to make binding decisions for the dominions would be an encroachment on their autonomy. The conference, as he envisaged it, was an important way to exchange information and foster understanding but it had no authority; decisions would have to be made by the parliaments. The conference’s final report, which affirmed King’s belief, marked a decisive step in the evolution of the British Commonwealth of Nations (a term that had received imperial statutory recognition in the Anglo-Irish treaty of 1921). The affirmation was an admission that there would be no centralized empire. It left undecided how the unity of the Commonwealth might be achieved or if, indeed, the Commonwealth would survive. King had no misgivings. He believed that self-governing members of the Commonwealth shared profound social and political values and so would agree on major issues if there was no coercion. His analogy was the family: the dominions, like children, would grow up but they would not be tempted to slam doors or leave home if their autonomy was acknowledged. For him the recognition of the self-governing powers of the dominions would strengthen rather than weaken Commonwealth unity.

Among the advisers who accompanied King to the 1923 conference was Oscar Douglas Skelton, a political scientist at Queen’s University in Kingston and a biographer of Laurier. He attracted King’s attention by his lucid comments on Canadian autonomy and, after the conference, was persuaded by King to become a departmental counsellor in 1924 and then under-secretary of state for external affairs in 1925. The appointments confirmed King’s sound judgement. Skelton had a phenomenal capacity for work and a talent for organizing material and producing memoranda or speeches of remarkable brevity and clarity. He soon became King’s most trusted official. Skelton did not always agree with King – he was, for example, more sceptical about the benefits to Canada of membership in the Commonwealth – but he expressed his opinions frankly and then loyally accepted King’s decisions.

External affairs, however, and King’s crucial role at the Imperial Conference attracted little attention in Canada. Fortunately the political situation at home was promising. It was becoming easier to make concessions to the farmers because economic conditions were improving and because the protectionist wing of the Liberal Party had been weakened by the resignations of Fielding and Gouin for health reasons. At the same time the divisions within the Progressive Party were deepening. In 1924 the government was able to reduce some tariffs and still promise the first surplus since before the war. A few high-tariff Liberals voted against the budget but, more significantly, the moderate Progressives voted for it. King was now confident that the voters would reward his efforts and he dissolved parliament the next year.

King was wrong. He had pushed his party as far as he had dared in the direction of lower tariffs and had defended Canadian autonomy within the empire, but electoral results in October 1925 constituted a major setback. The Liberals did increase their representation in the west by 18 seats; however, this gain was offset by the loss of 10 seats in Ontario and 19 in the Maritimes, where King’s courting of the Progressives was resented. The Liberals ended up with 99 seats, of which 59 were from Quebec. The Conservatives, on the other hand, gained seats in every region for a total of 116, just short of a majority. The Progressives fell dramatically to 24, although they could find some consolation in the fact that they would hold the balance of power in the new parliament.

Not only had King led the Liberal Party to defeat but, along with eight other cabinet ministers, he had lost his own seat. Many observers, including Governor General Lord Byng*, assumed that he would resign and allow Meighen to take over. But King would not concede. He insisted on meeting the house, convinced that the Progressives would support his government rather than see it replaced by the Conservatives. For a few tense months King proved to be right. The Progressives voted for the throne speech of 8 Jan. 1926 and then for the Liberal budget in April. King also won the support of the two Labour mps (James Shaver Woodsworth and Abraham Albert Heaps*, both from Winnipeg) by introducing a bill for old-age pensions, though it would be defeated in the Senate. King himself was back in the commons after a by-election in Prince Albert, Sask., on 15 February and the Liberal government seemed likely to survive the session. It even seemed possible that it could survive one or two more.

King’s plans were upset by a scandal in the Department of Customs and Excise. There had been collusion between smugglers and members of the department to run goods into Canada from the United States. King had known for some time that there were problems and had moved the minister, Jacques Bureau*, to the Senate in September 1925 and appointed a successor, Georges-Henri Boivin, to reorganize the department. The Conservatives, however, were not impressed and saw the corruption there as an opportunity to defeat the Liberals, knowing that the Progressives, who had identified their party with honest government, would find it difficult to support the administration. King avoided any debate on the scandal as long as possible but in June 1926 the house had to deal with the report of a parliamentary committee on the scandal. When the Conservatives moved a vote of censure, King arranged a series of delaying amendments but it was clear that the Progressives were divided and that the government would likely be defeated on the final vote.

King’s response was to avoid the vote by asking the governor general to dissolve the house and force another election. Byng refused on the grounds that Arthur Meighen should be given a chance to form a government. Meighen was prepared to try. On 27 June King speculated in his diary on his opponent’s prospects. “Meighen too will fall heir to some difficult situations – Western provinces. . . . If he seeks to carry on I believe he will not go far. Our chances of winning out in a general election are good. I feel I am right, and so am happy may God guide me in every step.” The following day King resigned. Meighen succeeded in forming a government and in passing a vote of censure but his hopes of ending the session quickly were frustrated by King’s refusal to cooperate. King arranged for a series of resolutions criticizing the new government. Enough Progressives, embarrassed at having to support Meighen, backed the Liberals in a vote of no-confidence on 2 July that narrowly defeated the new government. Byng then accepted Meighen’s advice and dissolved parliament.

The election of September 1926 was decisive for King’s career. Support for the Liberals had declined under his leadership and now the party had the additional handicap of fighting under the cloud of the customs scandal. King, however, fought an aggressive campaign, nationally and in Prince Albert. He argued that the constitution had been violated when Byng had refused him a dissolution but granted one to Meighen. In constitutional terms, Byng was right and King was wrong. Politically, however, King was the winner. He had focused attention on Byng’s decision even though many Liberals doubted whether the electorate would be interested. The outcome seemed to confirm his judgement. The constitutional issue distracted voters from the customs scandal, with King posing as the champion of Canadian autonomy against an interfering governor general. The decisive factor was the cumulative effect of King’s sustained efforts over five years to regain the confidence of the dissident farmers. The moderate Progressives had concluded that they preferred a Liberal to a Conservative government and in a number of ridings had agreed to nominate a Liberal-Progressive candidate. The Liberals won 116 seats and, with the support of 10 Liberal-Progressives, would have a clear majority. King himself retained his seat for Prince Albert.

The next few years were good ones to be in office. The Canadian economy expanded as post-war recovery in Europe and prosperity in the United States increased the market for Canadian cereals, minerals, and wood products and as domestic demand grew for Canadian automobiles and other manufactured goods. The federal government could cut taxes and still reduce its debt and have a modest surplus. The provincial governments wanted financial concessions but these claims were nothing new and King’s skill as a negotiator would stand him in good stead. Late in the decade there were signs of economic trouble, including weakening newsprint and grain markets and excessive stock-market speculation, but optimism proved hardy. King continued to believe that his government was performing well and that the voters would show their gratitude.

The Imperial Conference of 1926 came only two weeks after King had returned to office in September. This conference was important because it attempted to define the nature of the British Commonwealth of Nations. King did not initiate the discussions. He was prepared to live with an undefined relationship with Britain, confident that he could defend Canadian autonomy when necessary. James Barry Munnik Hertzog, the prime minister of South Africa, was more impatient: he threatened to leave the Commonwealth if the conference refused to draft a declaration that would affirm the independent status of the dominions. He had the support of Ireland but not the prime ministers of Australia or New Zealand. King played an important role as a mediator. He favoured the middle ground of a declaration of autonomy but not of independence. After two weeks of negotiations the conference agreed on a definition of Britain and the dominions: “They are autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.”

This definition did not end the debate. Hertzog interpreted “freely associated” to mean that South Africa could leave the Commonwealth if it chose to; the British did not agree. The definition was significant, however. Equal status meant that Britain could no longer assume that its foreign policy should be the policy of the Commonwealth. It also meant that Canada, like the other dominions, could develop a diplomatic service and a foreign policy of its own. The Imperial Conference of 1926 and the Statute of Westminster of 1931, which would give this new status legal definition, confirmed that the British Commonwealth of Nations would be a voluntary association, with its strength to be determined by the decisions of its respective members. Canada’s diplomatic service quickly took shape. Charles Vincent Massey*, the first representative to be appointed abroad with full diplomatic status, was named envoy to the United States in November 1926. This assignment was followed by the appointment of Philippe Roy to France in 1928 and Herbert Meredith Marler* to Tokyo in 1929.

King had no misgivings about the new imperial arrangement put in place in 1926. He assumed that Canada would have to continue to defend itself vigilantly against British predilection for centralization but any defence would be easier now that the autonomy of the dominions had been formally conceded. As before, King was not concerned that the Commonwealth might not survive. He believed that ethnic ties and a common political heritage were powerful bonds. Independence was not an option he considered, presumably because membership in the Commonwealth would not encroach on Canadian autonomy and would give Canada a status and a security it would not have as an independent country.

Back in Canada, King had to deal with continuing regional dissatisfaction. The Maritimes were aggrieved because they were not sharing in the prosperity of the rest of the country and were convinced that federal tariffs and railway freight rates were to blame. The prairie premiers complained that federal reluctance to relinquish control of their natural resources was discriminatory. The premiers of Ontario and Quebec objected to the limitations placed on their authority to develop hydroelectric power by federal jurisdiction over navigable streams. At the Dominion-Provincial Conference of 1927 King used his conciliatory skills and held out concessions to each region if they raised no objections to the offers made to the other regions. And so the Maritimes got higher subsidies and lower freight rates, the prairie provinces got control of their natural resources without losing a compensatory subsidy, and Ontario and Quebec got the right to distribute water power developed on navigable streams. For the moment King’s approach had appeased the regional demands.

This relative political harmony was linked to the prosperity of the mid 1920s but it can also be seen as the end of a long era of nation building. The three-pronged National Policy of Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald*, had achieved its objectives. Most of the arable land offered to homesteaders on the prairies was now occupied and for the first time in half a century the federal policy of assistance to agricultural immigrants was questioned. Railway policy was also being modified. The government-owned Canadian National Railways, under the aggressive management of Sir Henry Worth Thornton*, had spent federal funds to develop an integrated railway system. The success of this investment seemed confirmed by 1928 when the operating revenues of the system exceeded the interest payments on the railways’ bonds. The third prong, the tariffs, was a major subject of political debate – farmers still deemed them too high – but they were no longer a dynamic factor in the Canadian economy.

King had no new policy to substitute for the old National Policy. He did reintroduce old-age pensions after the 1926 election but he did not follow up with other measures of social security for individuals in an increasingly urban and industrial Canada. Instead of spending the increased revenue which prosperity provided, the government used its annual surplus to reduce its debt and in 1927–28 it lowered the sales and income taxes. King saw no reason to question this frugality. By reducing taxes and so reducing the costs of production, his government, he was sure, deserved credit for Canada’s economic growth and he expected to be rewarded at the polls.

The Republican victory south of the border in 1928 introduced a possible complication because President Herbert Clark Hoover was committed to raising the American tariffs on farm products. King used what influence he could to change Hoover’s mind. He agreed to help American agencies enforce Prohibition by making it more difficult to smuggle Canadian liquor into the United States. He also tried to take advantage of Hoover’s interest in a St Lawrence River seaway by suggesting that Canada was ready to negotiate an agreement. Hoover would not change his mind. The King government responded in the federal budget of 1930 by promising countervailing rates if the American government did increase its tariffs.

By then the good times were over, though not all Canadians realized this at the time. In Canada the onset of the world-wide depression of the 1930s differed by region and by industry. The Maritimes had already entered into severe economic decline. The overproduction of pulp and paper had meant lay-offs in northern communities as early as 1927. The price of western wheat dropped in 1928. In other regions, even in 1930, there might be some concern for the future but the factories were still operating. Richard Bedford Bennett, the leader of the opposition in parliament since 1927, argued that there was a crisis and demanded that the government do something. King was not impressed. It is revealing that there is no reference in his diary to the famous stock-market crash in October 1929; it would take two more years to push the government financially to the wall. King’s own investments were in government bonds and gilt-edged securities and it was easy for him in 1929 to assume that only speculators had been hurt. He also found the talk of unemployment exaggerated – in 1930 the Dominion Bureau of Statistics was only starting to register a drop – and surely next spring would bring higher prices and more jobs. It was, King believed, a temporary recession and just patience was needed.

The prime minister spent the early part of 1930 mulling over the timing of the next election and related budgetary options. What scant attention he paid to the appointment in February of Canada’s first female senator, Cairine Reay Wilson [Mackay*], was of a partisan nature. On the economic front his optimism led to an uncharacteristic slip in a debate on unemployment on 3 April 1930. The Conservatives argued that the crisis was so severe that Ottawa should offer financial assistance to the provincial governments, which were responsible for unemployment relief. King pointed out that no premier had asked for help and that, in Ontario, George Howard Ferguson had even denied his province had an unemployment problem. The federal Tories, according to King, were playing partisan politics, asking him to subsidize provincial Tory governments for no good reason, and he “would not give them a five-cent piece.” He did not often deliver such an unguarded statement and the opposition would make much of “the five-cent speech” in the election called for July.

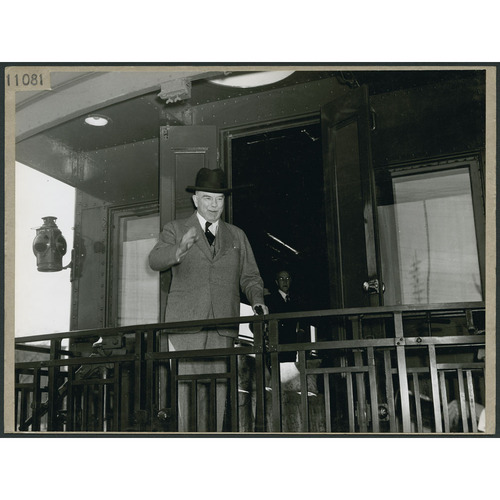

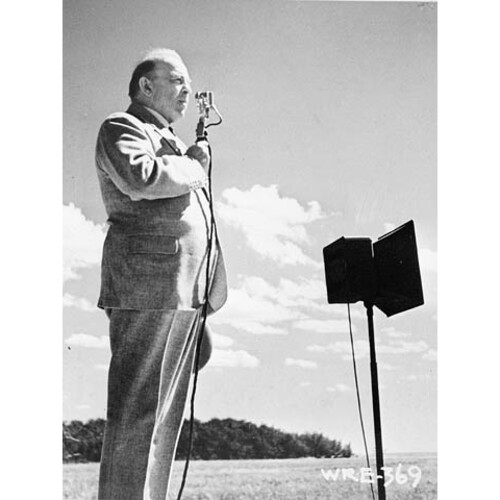

King was still confident that voters would appreciate his frugal financial policy. In the campaign he did not ignore the economic downturn but he offered caution and sound government as the appropriate response. On the other hand, Bennett, who used radio with telling effect, talked of an economic crisis and promised dramatic measures, including the use of tariffs “to blast a way into the markets that have been closed.” On the prairies, where wheat prices had dropped sharply, and in Quebec, where dairy farmers wanted protection against New Zealand butter, Bennett’s appeal swung enough votes to give the Conservatives a majority. Returned in Prince Albert, King would spend the next five years in opposition.

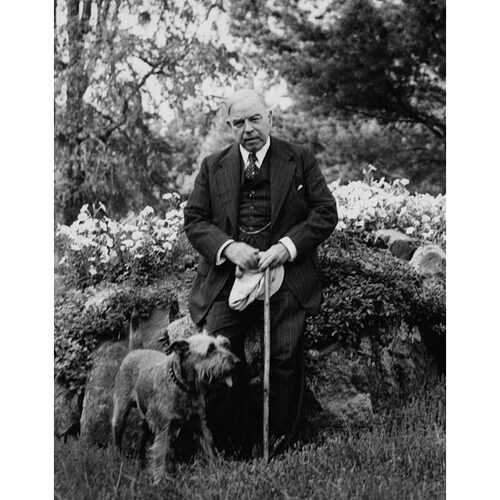

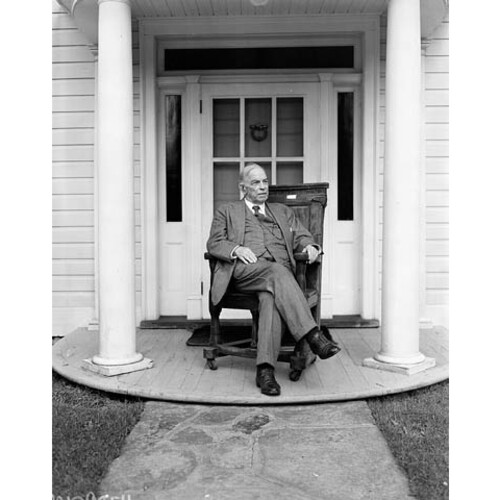

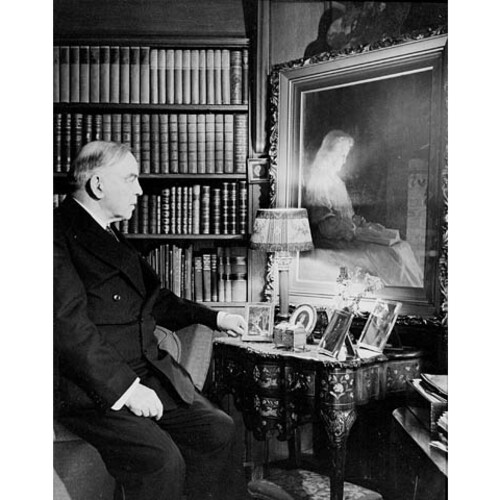

His lifestyle was now well established. At 55, he was a confirmed bachelor with few interests outside of politics. Laurier House, the Ottawa residence he had inherited from Lady Laurier and occupied since 1923, was a comfortable, yellow-brick abode maintained by a staff that included a valet, a cook, a chauffeur, and a gardener. Peter Charles Larkin*, a loyal Liberal businessman, had collected private funds to renovate it and pay for its upkeep. An elevator was installed. It took King and sometimes his invited guests to the third-floor library, where a portrait of his mother was prominently displayed. King occasionally had people for dinner but these were usually formal occasions. He was not a gregarious man and none of his colleagues and friends would visit him without an invitation. His closest friend was Mary Joan Patteson, wife of Godfroy Barkworth Patteson, a local banker with limited interests. Joan was a discreet and sympathetic woman who listened to King with patience and understanding and who rarely intruded her own problems into the discussions. King regularly talked to her over the telephone or dropped in for a visit to recount the difficulties or good fortunes of the day. The friendship was never a secret and it was a tribute to Joan’s discretion and transparent dignity that no scandalous rumours about the nature of the relationship were ever taken seriously.

King’s summer residence at Kingsmere was even more of a refuge than Laurier House. He expanded the property in the 1920s and 1930s and spent his summer months there to escape the sultry heat and social pressures of Ottawa. He rented a cottage on his property to the Pattesons and sometimes entertained foreign guests for lunch, but if he saw his colleagues or secretaries there it was only because he had asked them to make the trip to conduct business. King’s interest in erecting artificial ruins at Kingsmere – still one of its most fascinating features – emerged in 1934, when his grandfather’s house in Toronto was threatened with demolition. The Kingsmere collection actually began the following year, with a stone window frame from the Ottawa residence of the late Simon-Napoléon Parent*.

If King seemed settled in his ways, he was still a lonely man and politics was not enough to fill his life completely. He had no close family ties by this time; his surviving sibling, Janet (Jennie) Lindsey Lay, lived in Barrie, Ont., but they were not intimate. As leader of the Liberal Party he kept himself at arm’s length from his colleagues, who might try to presume on his friendship and might have to be jettisoned if the political winds changed. He did continue to correspond with acquaintances outside Ottawa and to talk to Joan Patteson, but this was not enough for a man who constantly needed the reassurance that he was loved. Pat, his Irish terrier, was important because Pat showed affection without making too many demands on his time. King, however, also found emotional support in more unusual ways. In 1916, after visiting the graves of his sister Isabel Christina Grace and father in Toronto, he had noted in his diary, “To me the spiritual presence of both Bell & himself was far more real than their graves which my eyes were witnessing.” His faith that his family (especially his mother) and others were somehow still watching over him became more important as time passed; he regularly saw coincidences as a sign of their presence and interpreted his dreams as evidence of their affection and support. This faith in itself did not make King unique but the need for signs of approval from the spirit world gradually led him to seek confirmation in more eccentric ways. He was intrigued by forecasts of the future based on tea leaves and his horoscope, consulted a fortune-teller, and during his years in opposition, when he had more leisure time, tried to make contact with the spirit world through other means, including the Ouija board and sessions with a medium. King occasionally expressed scepticism about the messages he received – he justified his interest by calling it psychic research – but he was still fascinated by the apparent contacts with the departed. He did not seek their political advice; his political decisions were based as always on his own analysis of situations. The content of the messages was less important than the evidence that the spirits were present and watching over him. This reassurance gave him the strength to deal with the stresses and strains and with the isolation of politics. In a paradoxical way, his eccentric links with this other world made it more possible for him to cope with the normal pressures of a political career.

The normal pressures were intensified after the 1930 election by allegations of corruption. What became known as the Beauharnois Scandal had its roots in a scheme to divert water from the St Lawrence into the Beauharnois Canal near Montreal to develop hydroelectric power. In March 1929 the King government had authorized a diversion after confirming that it would not interfere with navigability on the river. The Beauharnois Light, Heat and Power Company, however, saw this approval as only the beginning. It looked forward to a seaway with most of the St Lawrence diverted into its canal. The potential profits were enormous. The corporation, apparently concluding that it was necessary to keep the Liberals in power, funnelled more than half a million dollars into their campaign fund in 1930. This contribution proved awkward for the party when it became public knowledge after the Liberal defeat. Even more embarrassing for King was the disclosure that he had gone on a holiday to Bermuda with Wilfrid Laurier McDougald, the chairman of the Beauharnois board, and that McDougald had paid King’s hotel bill and submitted it to Beauharnois on his expense account. Between June 1931 and April 1932 committees of the commons and the Senate investigated the many related allegations.

King managed to have his name cleared. McDougald explained that he had submitted his bill by mistake; nobody seemed concerned that King’s acceptance of McDougald’s generosity might be interpreted as a conflict of interest. The donation to the Liberal campaign was more difficult to deal with. King could argue that his government had protected the public interest when it allowed the diversion of water and had made no further commitments to the corporation, but he knew that many Canadians would remain unconvinced. Though the scandal did no long-term damage – nor did it lead to any major reforms in the financing of the party – it put the Liberals, King conceded in parliament on 30 July 1931, “in the valley of humiliation.” His solution was to isolate himself from party finances. Liberal bagmen would continue to collect and distribute campaign funds. As leader, King would not be told who the contributors were, so his political decisions would not be affected by their identity. This solution left him with a clear conscience but it still left the party largely dependent on undisclosed donations from private corporations.

In the meantime Bennett had begun his administration actively, as he had promised. In a special session of parliament he offered $20 million as a palliative measure for emergency relief, an unprecedented amount for a federal government that had no direct constitutional responsibility for relief. To solve the larger economic crisis, his response fell into the traditional pattern of a Canadian Conservative: he raised the tariff rates sharply on manufactured imports to encourage domestic production and create jobs. Unfortunately exports dwindled, the prices for Canadian goods continued to decline, and unemployment rose. By 1932 Bennett had shifted his hopes to the Imperial Economic Conference in Ottawa, where a number of trade agreements with Britain and other dominions were worked out. An effective negotiator, he won some preferences, especially in the British market, without making major concessions. Though Bennett trumpeted his achievements and promised Canadians that economic recovery was on the way, the trade preferences unfortunately still left Canadians with unsold goods and deflated world prices.

Bennett, who initially acted as his own minister of finance, had to face declining revenues as well as ever stronger demands for federal aid. He raised taxes slightly but revenues declined with the economic slowdown. Further tariff increases would have little effect because the existing structure already excluded most foreign competition. Bennett’s only choice seemed to be the reduction of expenditures, especially relief costs. He tried to keep aid to the provinces to a minimum by hard bargaining; in the unemployment and farm relief acts of 1931–32 he even refused to disclose the amount of federal funds available in order to negotiate more effectively. At the same time he showed his frustration with the depression by stressing law and order, denouncing strikes and demonstrations, and insisting that his administration was doing everything possible.

After King had dealt with the Beauharnois problems, he proved to be an effective opposition leader. The depression of the 1930s was of unprecedented severity in Canada. The dependence on exports of raw materials and farm products meant that Canadian providers were especially vulnerable in a world where nations raised tariffs to protect their producers. Western farmers were doubly unfortunate because not only did prices reach historic lows, but in many regions drought, rust, and grasshoppers also meant crop failures. In cities, factories closed because consumers could no longer buy. Desperate Canadians had to turn to governments when they had no other place to turn, first for food and shelter and then for any means to restore their hope. The depression brought regions and classes into conflict and encouraged demagogues to propose radical and unorthodox policies. King seemed an unlikely leader for this troubled time. He had earned a reputation for being cautious, a man of compromises and half measures. In a world where the battle seemed to be between left and right, with communism and fascism at the extremes, King looked indecisive, even colourless. Yet within five years he would be back in office, at the head of the largest majority enjoyed by any party up to that time. He kept the Liberals together while the Conservative Party disintegrated and new political parties emerged to compete for votes. It was no mean achievement. As he had explained in 1929 to a correspondent, “The supreme effort of my leadership of the party has been to keep its aims and purposes so broad that it might be possible to unite at times of crisis under one banner those parties, which for one reason or another, have come to be separated from the Liberal party.” By 1923 most Progressives would have rejoined it. In 1931–32, however, unity seemed a distant goal: the party was torn between high and low tariff factions, and on the front benches of opposition King had few strong supporters at his side.

Like Bennett, King was slow to recognize that politics would be transformed by the depression. He had begun his years in opposition convinced that his administration had not deserved defeat. The economy had flourished, he believed, because of his government’s financial caution. The recession, if it was a recession, could be blamed on the speculative excesses of businessmen and on the weather cycle. The worst mistake Canada – and the rest of the world – could make was to react by raising tariffs and restricting international trade. Bennett, from King’s perspective, had won election by exaggerating the threats to the Canadian economy and by rashly promising that he could somehow use the tariff to counteract international and climatic constraints. Voters, King believed, would soon learn that they had been deceived and would come to appreciate the Liberal years of frugal administration and freer trade.

King thus saw little need to reconsider or revise his political assumptions. The Conservative government was clearly in political trouble and King was content to draw attention to its difficulties. He repeatedly reminded the house of Bennett’s election promises. He denounced the federal deficits as irresponsible without suggesting how budgets could be balanced. He did not object to aid to the provinces – the need was too apparent – but he did denounce the “blank cheques” parliament was asked to approve for relief, and delayed the passage of these bills over the objections of caucus members who feared constituents might conclude that the Liberals had no sympathy for those in distress. And each year, after the throne speech and the budget, he introduced amendments that blamed the depression on Bennett’s high-tariff policy.

He was still responding as a traditional Canadian Liberal, convinced that the depression would end only with the restoration of international trade, when Canadian producers would once more have markets. Sure that high tariffs had made matters worse, he was encouraged too by the fact that Bennett and his government were being widely blamed and would surely be defeated. It was enough to focus attention on trade and tariffs until voters had the opportunity to remedy their mistake. King, however, gradually realized that for many Canadians, including some long-time Liberals, waiting was not good enough. Talk of tariffs had little relevance for parents who could not feed their children or for farmers who could not buy seed or hay. For them, the capitalist system seemed to have failed and tinkering with tariffs would accomplish nothing. It was also significant that voters would have more choice in the next election. The more radical Progressives and the Labour members in the commons had founded a new political party in 1932 – the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation – which offered the socialist alternative of government planning and public ownership. That same year, in Alberta, evangelist William Aberhart became a convert to monetary reform in the shape of social credit, a doctrine that advocated the distribution of money for purchases by consumers. Within two years he had transformed it into a political platform. By 1935 Social Credit candidates would come forward federally, and dissident Conservatives would form a new party. Many Liberals in the west, where the impact of the depression was most severe, were convinced that their party would have to adopt more radical measures to be relevant; more traditional Liberals rejected such policies as irresponsible.

King’s response reflected his fundamental commitment to finding a consensus among “liberally-minded” Canadians. He did not expect to convert the Tories, whom he believed were wedded to big business, or the socialists, who wanted a monopoly of power for the workers. Criticism from his own caucus members, however, he took seriously. He might regret their impatience but he would not ignore them. His role was to keep the party united. By 1933 he had reluctantly concluded that traditional Liberal preconceptions were not enough. If the party was to survive, it would have to face the challenge of the depression more directly. Here his talents as a conciliator would be crucial. Although lower tariffs would be part of a new Liberal platform, the most controversial issue would be inflation. King and his more conservative followers still equated inflation with theft, but, for indebted producers especially, inflation seemed the only way to meet their financial obligations. King’s compromise was a government-controlled “central bank” that could modify the money supply on the basis of “public need.” He was proposing an institution, not a policy. He succeeded because the moderates saw the bank as an agency that could protect sound money and the radicals saw it as an agency that could introduce a policy of controlled inflation. The significance of this compromise should not be minimized. It recognized that the state should play a positive role in determining fiscal policy. It certainly implied more intervention than did the Bank of Canada legislated by Bennett in 1934, which was to be an agency of the chartered banks.

This new platform was quite satisfactory to King. It placed the party in the centre of the political spectrum, more open than the Conservatives to regulating business without resorting to the socialist panacea of government ownership. It was also important to King that the platform had been approved in 1933 by both the conservatives and the radicals in the Liberal caucus. Some, among them Vincent Massey, wanted to take Liberalism in different directions, and not necessarily with King at the helm. With party unity assured, King eagerly awaited the next election. Late in the 1934 session he denounced Bennett for holding on to office when he no longer had popular support and promised that if he insisted on meeting the house for a fifth session, the Liberals would obstruct and force an election. In January 1935 the political situation changed when Bennett made five radio speeches known as the New Deal broadcasts. “The old order is gone,” he told a startled audience, and he announced that he was for radical reform through government intervention. In the next session, he promised, he would introduce appropriate legislation. There was more rhetoric than substance to these broadcasts and Bennett, in contrast to King’s approach to leadership, had not consulted his colleagues. Confident that it had the jurisdictional authority, the government nonetheless passed the Employment and Social Insurance Act early in 1935. Bennett certainly won the attention of Canadians who, after five years of depression, wanted to believe that a political leader could end the crisis.

King quickly revised his strategy. There would be no obstruction when the House of Commons met. He persuaded his caucus that the New Deal broadcasts were not about reform but were really the first phase of the election campaign. The Liberals must not appear to be opposed to reform. It would be wiser to seem cooperative and encourage the government to introduce the promised laws immediately. The embarrassed government had none prepared and when measures were introduced, they were less radical than the broadcasts had suggested. The New Deal, however, did mean an expansion of the federal role in marketing farm products, regulating business, and supervising working conditions. In constitutional terms it meant federal intervention in assumed provincial jurisdictions. King avoided any direct challenges. He persuaded caucus that the party should express its constitutional reservations and then vote for the legislation.

The changed strategy worked. The Liberals remained united, at least in public, but the Conservatives became deeply divided. By the end of the session the government’s claim to be the party of reform was discredited and in July 1935 some dissident Conservatives led by Henry Herbert Stevens* had even formed a separate Reconstruction Party. In the federal election of October the Liberals were returned with 173 seats, the largest majority on record, with members from every province, while the Conservatives were reduced to a rump of 40 members. The popular vote, however, told a different story. The Liberals received only 45 per cent, almost unchanged from the previous election. The dramatic change was the drop for the Conservatives and the support of 20 per cent for the new parties: the CCF and its socialism, Reconstruction and its emphasis on regulating business, and Social Credit and its panacea of inflation. If the choice was between “King or chaos,” as the Liberal slogan put it, a good many Canadian voters were prepared to risk chaos.

The next four years would be a difficult time for the country. For its new prime minister it would be a stern test of his political skills. His experience and confidence showed in his cabinet. King again took on external affairs. Ernest Lapointe, still his closest colleague, returned to justice. The financially conservative Charles Avery Dunning* was persuaded to become minister of finance, and from among the new mps King appointed Clarence Decatur Howe*, who had business experience, to the newly created portfolio of transport. The cabinet was recognized as an able group, and King would give his ministers a good deal of autonomy in the administration of their departments, but King, more than ever, was in charge. He set the government’s agenda and chaired the cabinet discussions. After some slow improvement in economic conditions, 1937 saw another downturn, especially on the prairies, where the summer was the driest on record. Regional grievances fed on the frustrations of deferred recovery, and the government again became a popular target. The divisions within the Liberal Party, which reflected regional rivalries, were compounded by a series of international crises that threatened to involve Canada in a European war.

The new government, as one of its first problems, had to decide on its international obligations as a member of the League of Nations. King had supported membership – it enhanced Canada’s status as a nation and provided evidence that Canada favoured the peaceful settlement of international disputes – but he had shown little interest in the debates at League headquarters in Geneva. Canada’s foreign policy had been mainly confined to relations with Britain and the United States, and King expected to deal with these countries directly. Shortly after the election, however, his government was faced with a request from the League to impose economic sanctions on Italy because it had invaded Ethiopia. The cabinet agreed to apply sanctions but the discussion made it clear to King that if the League went on to propose military intervention, the cabinet and the country would be deeply divided. The request for military sanctions never came because Britain and France backed away from any confrontation with Italy’s Fascist leader, Benito Mussolini. King nevertheless learned an important lesson: membership in the League might have serious political consequences for Canada. He took steps to minimize the risk. Though he affirmed, in the commons and later in Geneva, his support for the League as a necessary institution for the resolution of disputes, he bluntly rejected the idea of the League as a military alliance against aggressors. Canada, he told the League’s Assembly in 1936, did not support “automatic commitments to the use of force.” Editorials in much of the Canadian press applauded. King’s political faith in non-intervention, and his fear of domestic division, can be seen too in his decision to distance Canada from the Spanish Civil War in 1937 and his refusal to modify Canadian immigration regulations to admit European Jewish refugees.

For King, Canada’s economic problems had higher priority than international relations, but he had no simple solution to the complex challenges of the depression. Although he had shown a willingness to consider extending the role of government when party unity seemed to require it, he was still reluctant to take new initiatives. His caution meant that his government’s honeymoon was brief. King’s only specific election promise had been to negotiate a trade treaty with the United States. Bennett had already begun the discussions but political interests on both sides of the border had delayed matters. In November 1935, within two weeks of taking office, King was in Washington to make the best deal possible. He wisely enlisted the support of Cordell Hull, the American secretary of state and an evangelist for expanding international trade. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, however, was the key. King and Roosevelt found it easy to discuss their political concerns. Roosevelt had a talent for putting visiting heads of state at ease and King could talk knowledgeably about United States politics and politicians. In the trade details King was well prepared and he returned to Canada with a treaty, which, modest in scope, gave Canadian farm products some welcome access to the American market.

He was also encouraged by a conference with the provincial premiers, in December 1935 shortly after the election. He was confident that a change in governing style would make a difference, that his emphasis on consultation would smooth relations. The premiers faced declining revenues and higher welfare costs and needed federal grants and loans to reduce their deficits. The national government had deficits of its own and hoped that provincial demands could be limited through the elimination of extravagances or duplications of welfare payments. At the conference King pleased the premiers by increasing the federal grants until the spring of 1936; his talk of a federal commission to supervise welfare payments and the possibility of constitutional amendments affecting provincial jurisdiction over social policy did not attract much attention. He had already referred Bennett’s Employment and Social Insurance Act to the courts, which would strike it down as exceeding federal jurisdiction. King’s objective at this stage was a federal system in which each level of government would be able to pay for its programs out of its own tax sources. He was no more precise because he had no concrete measures in mind and assumed that any new distribution of powers would emerge from discussions with the provinces.

King, however, soon found that confrontation was unavoidable because, without more federal aid, some provinces faced bankruptcy. William Aberhart, Alberta’s Social Credit premier since August 1935, was a populist with little concern for convention. In 1936 he could not refinance an issue of maturing provincial bonds without a federal guarantee of the interest payments. When C. A. Dunning suggested some federal supervision of provincial finances in return, Aberhart refused and extended the term for the bonds while halving the interest rates. Then, in 1937, under pressure from his backbenchers, he passed legislation to compel chartered banks to lend money to Albertans. When the newspapers criticized this measure Aberhart retaliated with a bill that obliged them to publish press releases giving the government’s side of the story. King’s response was to disallow the bank legislation and to refer the newspaper bill to the Supreme Court of Canada, which nullified it as unconstitutional.

King could claim to be standing up for civil rights in Alberta by defending the banks and the newspapers but he was less forthright in Quebec. In 1937 Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*, the Union Nationale premier, passed the Act Respecting Communistic Propaganda (the so-called Padlock Law) to intimidate labour leaders and “agitators” by threatening to lock up their offices for any alleged communist activities. King’s government, which had already repealed the section of the Criminal Code prohibiting unlawful associations, considered disallowing this act but Ernest Lapointe believed such a move would be politically disastrous for the Liberal Party in Quebec. King and his English-Canadian colleagues did not question Lapointe’s political judgement and so, as King recorded in his diary in July 1938, “we were prepared to accept what really should not, in the name of liberalism, be tolerated for one moment.”

Aberhart and Duplessis might show little respect for civil rights but the rift between the federal and provincial governments had a more basic cause. The provinces, dependent as they were on revenues from direct taxes, could not provide even essential social services without subsidies or loans from Ottawa. Thomas Dufferin Pattullo*, the Liberal premier of British Columbia, whose concept of liberalism embraced the provision of work and wages, committed his government to construction projects for which it had no funds. When King refused to provide money for a bridge across the Fraser River, Pattullo was furious. Ontario’s Liberal premier, Mitchell Frederick Hepburn*, was critical for quite different reasons. He objected to federal grants to western provinces to finance relief measures because most of the money came originally from Ontario taxpayers. In 1937 he announced that he was no longer a “Mackenzie King Liberal.” Other premiers might be less outspoken but all of them were facing demands for social services they could not afford. If there was to be effective coordination, the onus would have to be on Ottawa. Privately King resented Hepburn and Duplessis’s narrow regionalism, but it was, he reasoned in his diary in December 1937, “just as well to have these two incipient dictators out in the open. The public will soon discover who is protecting their interests and freedom. . . . We will win in a ‘united Canada’ cry.”