Source: Link

Qanajuq (Kanneyuk, Kanajuq), known as Jennie and Jennie Kannayuk, Copper Inuit hunter, seamstress, and singer; b. c. 1903 on or near Victoria Island, N.W.T., daughter of Nerialaq and Taqtu (Taqtuk; she adopted the name Higilaq in 1915); m. Qiqpuk (Qigpuk, Samuel Kekpuk), and they had two sons and two daughters, of whom one son lived to adulthood; d. March 1931 in Coppermine (Kugluktuk, Nunavut) and was buried there in the Anglican cemetery.

Qanajuq, whose name means “sculpin” in Inuktitut, was a member of the Puivlik people, a nomadic group of Copper Inuit in the central Arctic. When she was a young girl, her father, Nerialaq, vanished while out on a hunt. Her mother, Higilaq, was an angakkuq (spiritual leader), and her stepfather, Ikpukkuaq (Ikpukhuak), was a respected and well-known hunter. In a story told by her childhood friend Annanak, Qanajuq once became sick just as the summer caribou hunt was about to start. Because the hunt was essential to the family’s survival, she hid her illness so that they could travel to participate in this event. She then recovered well enough to join in the hunt.

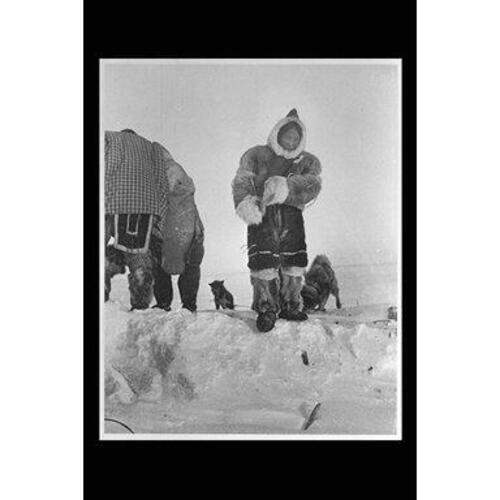

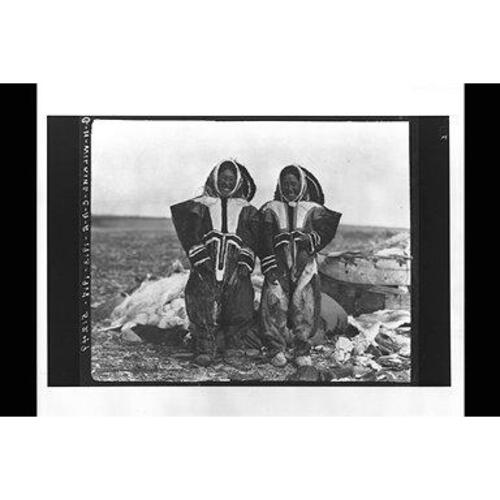

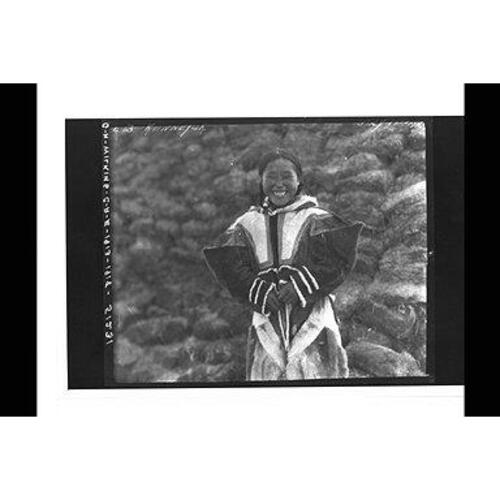

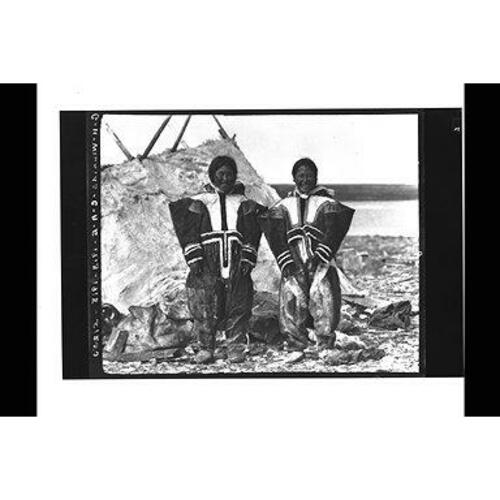

From April to November 1915 Diamond Jenness*, the anthropologist of the Canadian Arctic Expedition (1913–18) led by explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson*, travelled with Qanajuq and her family on Victoria Island, following their traditional seasonal movements. Jenness, who was adopted by Ikpukkuaq and Higilaq, became very fond of his little sister Qanajuq. In his 1928 book The people of the twilight, he gives the best surviving description of this bright and happy young girl: “Sculpin, or Jennie, as my colleagues christened her [a nickname derived from his surname], became a general favourite through her frank smile and merry laughter. More intelligent than most of her people, she knew how to keep out of our way, and spent many quiet hours in a corner mending the rents in our clothing, or gazing at the pictures in our books.” Qanajuq was a great help to Jenness in his attempts to record the songs of the Copper Inuit who visited the expedition’s headquarters. Some of them were apprehensive when asked to sing into the trumpet of the phonograph, but Qanajuq willingly recorded numerous songs. Jenness travelled with her family again in 1916. In The people of the twilight he recalls her charming companionship on that journey: “She laughed when the dogs chased a sandpiper, she laughed when she stumbled. Her laughter was infectious, and no merrier party ever tramped those northern meadows. She was only twelve years of age, or thirteen at the most, with all a child’s love of play and pastime; yet already she knew some of the responsibility of her sex.”

Sometime after the expedition was completed in 1918, Qanajuq married Qiqpuk, and by 1923 the couple had a boy, who was followed by two girls. All three children died in the late 1920s during an epidemic, possibly of influenza, which also took the life of Higilaq. Qanajuq’s fourth child, a son named Ahegona, was born on Victoria Island in 1929. The following year, while living at the island’s Rymer Point, the family was visited by Russell D. Martin, a physician who had been despatched to the central Arctic by the federal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King*. Martin found that Qanajuq had contracted spinal tuberculosis, an agonizingly painful disease that had already left her partially paralyzed. The doctor persuaded her to move to Coppermine, where he had built a makeshift one-room hospital and could give her better care. (Several tents near the building housed patients suffering from tuberculosis, which had taken hold in the settlement shortly after an infected and dying man, Uloqsaq*, arrived on the same plane that brought Dr Martin to the Arctic.)

In 1930 Diamond Jenness, then working at the National Museum in Ottawa, received a radio message from Jennie and Ikpukkuaq, urging him to return to the Arctic to visit them. Her message: “If you are coming I will make an artigi [coat] for you. When are you coming? Maybe I will die before you come. I do not know. When you come bring me some pretty calico. Now I am a little better. In the summer it was otherwise. – Kanneyuk.” Jenness replied: “I shall never forget my father and my younger sister. Though I would like to see you, it cannot come to pass. It is too far away. I am getting old. Do not be frightened. When we die we will meet each other. We will be happy all together.”

Desperate to meet with his supervisors to arrange better medical help for the people of Coppermine, Dr Martin flew to Ottawa in March 1931, leaving Qanajuq in the care of Richard Sterling Finnie, a photographer and film-maker. There was nothing Finnie could do for her, and she died with her husband and stepfather at her side. Her two-year-old son, Ahegona, watched as her body was covered with canvas, which was then sewn shut. She was buried in a shallow, frozen grave during an Anglican service. Qiqpuk, following her wishes, carefully placed a wooden box over her head: in her final days her breathing had been so restricted that she wanted to be sure she would have some air to breathe in her grave.

Qanajuq died without having received all the benefits of modern medical knowledge. Dr Martin’s urgent requests for better facilities and equipment were not acted upon by the federal government, led until August 1930 by King and then by Richard Bedford Bennett*. Especially disconcerting was the failure to provide her with a sunlamp, which was then thought to be an effective treatment for tubercular patients. Two years later her husband and stepfather died within a few months of each other. Ahegona had been small, sickly, and unable to eat solid food at the time of his mother’s death, but he was saved by being fed dog’s milk. He later went to school in Aklavik, where his English name, Bill, was changed to Aimé (Aime), which came more easily to the French-speaking Roman Catholic priests who taught there. Aimé returned to Coppermine in 1938. Dr Martin, however, never came back: following his 1931 visit to Ottawa to plead for greater assistance, the federal government had terminated the funding for his position. No new medical facilities were established in Coppermine until a nursing station was opened in 1947.

Interviews with elders conducted for the 1992 National Film Board documentary Coppermine show that Qanajuq remains a significant part of the story of Kugluktuk (which became the settlement’s name in 1996). The film recounts the tragedy of the tuberculosis epidemic among the Copper Inuit, and, in particular, the stories of Qanajuq’s life and death and of the failings of the federal government. Today, 13 of her recordings of chants, dance songs, and weather incantations are a permanent part of the collections of the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Que. So is her happy laughter, recorded between the songs.

The author interviewed Ahegona in Kugluktuk (Nunavut) between 24 and 26 Sept. 2002. Photographs of Qanajuq, under the name Jennie Kannayuk or Jennie Kanaiyuk, are held by the Canadian Museum of Hist. (Gatineau, Que.), Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913–1918 coll., nos.36916, 36919, 38685, 38993, 38997, 42347, 51230, 51231, 51246, 51247, 51248, 51249, 51250, and 51251.

Arctic odyssey: the diary of Diamond Jenness, ethnologist with the Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913–1916, ed. S. E. Jenness (Hull [Gatineau], 1991). Doreen Bethune-Johnson et al., Our Arctic way of life: the Copper Inuit (Toronto, 1986). Coppermine, directed by Ray Harper (film, Ottawa, 1992; available at www.nfb.ca/film/coppermine). R. [S.] Finnie, Lure of the north (Philadelphia, 1940). Diamond Jenness, The people of the twilight (New York, 1928; Chicago, 1959). Diamond Jenness and S. E. Jenness, Through darkening spectacles: memoirs of Diamond Jenness (Gatineau, 2008). Report of the Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913–18 (16v., Ottawa, 1919–28), 14 (H. H. Roberts and D[iamond] Jenness, Eskimo songs: songs of the Copper Eskimos, 1925). W. J. Vanast, “The death of Jennie Kanajuq: tuberculosis, religious competition and cultural conflict in Coppermine, 1929–31,” Inuit Studies (Quebec), 15 (1991), no.1: 75–104.

Cite This Article

David R. Gray, “QANAJUQ (Kanneyuk, Kanajuq), known as Jennie and Jennie Kannayuk,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/qanajuq_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/qanajuq_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | David R. Gray |

| Title of Article: | QANAJUQ (Kanneyuk, Kanajuq), known as Jennie and Jennie Kannayuk |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |