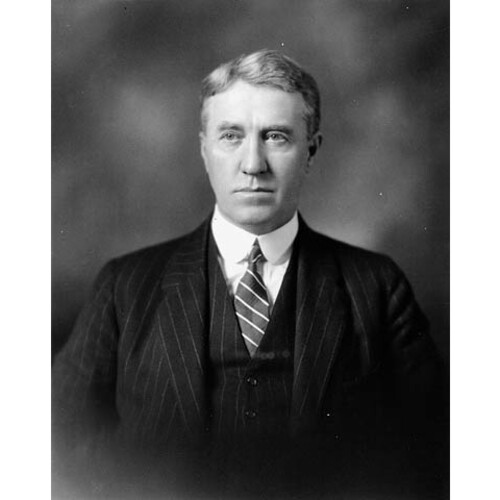

HAYDON, ANDREW, lawyer, political organizer, politician, and author; b. 28 June 1867 in Pakenham, Upper Canada, son of James Haydon and Eleanor (Ellen) Sadler; m. 24 Sept. 1902 Euphemia Macdonald Scott of Stafford Springs, Conn., and they had one son and one daughter, who did not live to adulthood; d. 10 Nov. 1932 in Ottawa and was buried there in Beechwood Cemetery.

Andrew Haydon gained his early education in Pakenham and Almonte before attending Queen’s College in Kingston, where he won first-class honours in English, history, and political science, and was deeply influenced by professors Adam Shortt and John Watson. After obtaining his ma (1893) and llb (1896), Haydon studied at Osgoode Hall law school in Toronto, graduating in 1897. He first established a practice in Lanark, but moved two years later to Ottawa, where in 1902 he became a partner in McGiverin, Haydon and Ebbs. When Harold Buchanan McGiverin, the firm’s senior partner, ran as a Liberal candidate for Ottawa City in the federal election of 1908, Haydon managed his campaign, and his skill in handling public relations and organizational work drew the attention of other Liberals, including Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, with whom he became friends.

Just over a decade later Haydon accepted a challenging assignment from the Liberal Party, which had been split by the issue of conscription during World War I. Leading Liberals from English Canada had supported this expedient and joined the Union government of Sir Robert Laird Borden, and in the election of 17 Dec. 1917 the anti-conscription Laurier Liberals had returned only 82 mps, 62 of whom represented Quebec constituencies. In August 1919, after Laurier’s death, a national Liberal convention was held in Ottawa to heal the rift and to select a new leader. Haydon organized the event with mp Charles Murphy and was its general secretary. Never one to seek the limelight, Haydon operated mainly behind the scenes and earned the gratitude and respect of many influential party members, especially William Lyon Mackenzie King*, who was chosen as Laurier’s successor.

From 1920 to 1922 Haydon served as general secretary of the National Liberal Organization Committee, which did preparatory work and raised funds for the federal election of 6 Dec. 1921, after which the party established a minority government. His friendly, forthright, sensitive, and informed advice, based on his exceptional ability to discern and recommend responses to shifts in public opinion, made him a valued adviser to King, as well as a key emissary in negotiating with the second-largest party in the House of Commons, the Progressives [see Thomas Wakem Caldwell]. Haydon left the office of general secretary in 1922 but would remain, according to political scientist Reginald Whitaker, the party’s “effective one-man national organization throughout the 1920s.” Even after he was called to the Senate on 10 March 1924, Haydon found time to pursue a wide range of cultural and literary interests. A devout Anglican, he was a strong supporter of Queen’s University and the author of two works of history.

In his capacity as the party’s chief fund-raiser, Haydon was brought into contact with important corporate leaders who could make contributions. His firm handled some of the legal affairs of the Beauharnois Light, Heat and Power Company (after 31 Oct. 1929 a subsidiary of the Beauharnois Power Corporation Limited) and of its board chairman, Liberal senator Wilfrid Laurier McDougald*. The company planned to divert the flow of the St Lawrence River through a canal to a huge new powerhouse, and its president, Robert Oliver Sweezey*, made large political donations to secure the consent of the governments of Canada and Quebec. Haydon and Senator Donat Raymond*, the co-treasurers of the federal Liberals, collected well over half a million dollars from Sweezey on behalf of their party, including a $50,000 payment to Haydon’s law firm that may have been contingent on federal approval of the company’s plans. The King administration passed the necessary order in council on 8 March 1929, and construction of the project began on 12 October after a grand ceremony attended by Haydon and such prominent figures as the governor general of Canada, Lord Willingdon [Freeman-Thomas*].

In the spring of 1930 Narcisse Maxime Cantin, a bitter business rival of Sweezey, began to leak damning information about Beauharnois to two United Farmers of Alberta mps, Robert Gardiner and Edward Joseph Garland. They in turn brought the subject to the attention of the House of Commons, and in June 1931 a select committee was established to investigate what came to be called the Beauharnois Scandal. King, whose party had been in opposition since losing the election of 28 July 1930 to Richard Bedford Bennett*’s Conservatives, emphatically denied that his government had approved the canal project in return for political contributions, and insisted that he did not even know the identities of donors to the party. No conclusive evidence to the contrary was produced, but the committee’s report harshly judged Haydon, McDougald, and Raymond, and a special Senate committee was created to determine what disciplinary action they should face. Since Haydon was ill with heart disease and could not appear before the committee, its members came to his home. He refused to implicate his leader or party, testifying, “I made no explanations or disclosures regarding campaign funds to Mr. King, or to any of his ministers or to anyone else.” Haydon acknowledged collecting donations from Sweezey, but stated: “He made no bargain with me.… No promises were asked and none were made. There was not the slightest relation between his contributions and the passing of the Order in Council.” He denied keeping any of the money for himself, saying that it had gone towards “the general organization work” of the party. “This whole matter of campaign funds,” he added, “is one on which the general public is liable to become very self-righteous. Everybody knows that elections cost money – and a lot of money – for perfectly legitimate expenses. The ordinary voter gives nothing.”

In retrospect, it is difficult to accept Haydon’s testimony that the huge contributions from Sweezey were unrelated to the government’s approval of the Beauharnois project. Haydon appears to have consciously taken the blame for the prime minister, who likely knew more about the donations than he admitted. On the subject of the Canadian public’s attitude towards political fund-raising, however, Haydon spoke the truth. It was no secret that parties routinely accepted money from individuals and corporations who sought favours in return, and in Sweezey’s case, it was only the size of the Beauharnois project and the correspondingly large contribution to the Liberals that was unusual.

The Senate committee’s report, completed in April 1932, was sharply critical of McDougald, who was forced to resign his seat; Raymond escaped with a severe reprimand. Andrew Haydon’s situation was more complicated. He had certainly received large sums of money from Sweezey, and the committee members judged his conduct to be “unfitting and inconsistent with his position and standing as a Senator.” They did not conclude, however, that he had benefited personally from these payments or pressured the prime minister to have the company’s plans approved, and in deference to his illness, years of devoted service, and honourable reputation, no action was taken against him. Nevertheless, the affair cast a dark shadow over a man whom King, according to his diary, regarded as a saint. After Haydon died of heart failure on 10 Nov. 1932, eulogies stressed his exceptional integrity and honesty, but the Toronto Globe, a leading Liberal paper, tacitly admitted that his reputation had been tarnished by the Beauharnois Scandal, which had given him “a prominence he had never sought.”

Andrew Haydon is the author of Pioneer sketches in the district of Bathurst (Toronto, 1925) and Mackenzie King and the Liberal Party (Toronto, 1930). He is the co-author, with W. L. M. King and John Lewis, of A message of Liberalism: including the resolutions adopted at the National Liberal Convention of August, 1919 (Ottawa, [1919]).

LAC, “Diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King,” 12 Nov. 1932: www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/prime-ministers/william-lyon-mackenzie-king/Pages/diaries-william-lyon-mackenzie-king.aspx (consulted 17 May 2017). Globe, 11 Nov. 1932. Can., House of Commons, Special committee on Beauharnois power project, [Minutes of proc. and evidence] (Ottawa, 1931); Senate, Special committee appointed for the purpose of taking into consideration the report of a special committee of the House of Commons … to investigate the Beauharnois power project …, Report and proc. (Ottawa, 1932). R. MacG. Dawson and H. B. Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King: a political biography (3v., Toronto, 1958–76), 1, 2. T. D. Regehr, The Beauharnois scandal: a story of Canadian entrepreneurship and politics (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1990). Reginald Whitaker, The government party: organizing and financing the Liberal Party of Canada, 1930–58 (Toronto, 1977).

Cite This Article

T. D. Regehr, “HAYDON, ANDREW,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/haydon_andrew_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/haydon_andrew_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | T. D. Regehr |

| Title of Article: | HAYDON, ANDREW |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2025 |